How important is a nail?

You know, one nail? Pointy thing, goes through wooden walls, binds shoe to hoof (prior to glue), you know… A nail?

How significant is a nail? One nail? How much does a nail cost? A penny? Less than one dollar, probably; less than one English pound, certainly.

And yet…

The real question is…

How much is one nail worth?

FOR WANT OF A NAIL the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

Put another way, how much is one kingdom worth? Certainly more than the price of a single horseshoe nail… And yet? That old English proverb / poem has the right of it, at least sometimes.

This proverb / poem teaches all kinds of things about opportunity and scarcity and resource management.

All of us as Magic players can relate whole kingdoms of accomplishment lost (or never found) based on one missing card / land drop / nail. In the Top 8 of a somewhat long ago US Nationals, my friend Josh Ravitz would Top and TOP and TOP again… All in search of the one land that he needed to smoke out Neil Reeves in game 1; he never found it and Neil ended up making the US National Team. Josh would finish Top 16 at Worlds that year in another close-but-dissatisfyingly-distant admirable finish… One match out of Top 8 in a tournament where he both presented 61 in a good matchup Day 1 (oops) and conceded to a friend and former teammate on Day 3; that friend—who had better breakers than the selfless Josh—subsequently lost to Akira Asahara in the win-and-in. Josh had beaten the winning Ghazi-Glare deck (half that Top 8) repeatedly on Day 1.

World Champion in a different universe?

Kingdom and kingdoms.

In other contexts we curse the nth land drawn, or can give away a game, whatever. The value of these things shifts, ebbs, rises up, or washes away like quicksilver. Like the nail, the value of these seemingly tiny lands, mental slips, misplaced moments of generosity, stacks of good matchups…are driven by context, by immediate need.

… And forgotten later.

I assume that almost every run of big tournaments has a dozen such stories.

The useful things you learn via good Magic articles are “just” tools for the most part rather than iconic First Principles. It seems silly to have to mention this lucky thirteen years post-“Who’s the Beatdown?” but any and all are driven by context. Every difference that makes the difference is driven by context. The trick is to figure out when to use which tool rather than applying the tools you happen to like to inappropriate contexts.

My assumption is that today (like, literally today) innumerable aspiring brewsters are searching for the next Jeremy Lin, the next Gnarled Mass, what they perceive to be that tournament-cracking “insane” [Hayne] Feeling of Dread.

Useful Tool Alert! What they should be looking for is not a famous-making flagship, but rather the next nail. Not what, perhaps, but when.

The vital flaw in “misplaced flagship” thinking is one of perspective, perhaps, but tools, certainly.

Most brewsters realize that they can differentiate themselves and their ideas only by differentiation. Knowing that much they often use strange cards, presumably, so they can point at them. Look at my [BLAH]. It’s so effective. I’m so rouge (sic).

The reality is that even the best Feeling of Dread is no deck. It’s no deck idea. Confused—if well-meaning—pundits and brewsters point at it like cavemen waving around iPhones. Why doesn’t this kill deer / harvest crops / make that wide-hipped cavewoman love me? To treat such a precise tool as a flagship—an Arcbound Ravager or Glare of Subdual—misses its wonderful value entirely. What makes it interesting is, like the nail, Feeling of Dread rises up to become one of the most important cards in the format only when you already have horses, messenger-knights, a kingdom with a war to fight already.

In the present case Hayne & co. already had a superior strategy. Anyone who saw the miraculous appearance of a lethal flock of Angels knows the force of the miracle mechanic. This was the context that team Mana Deprived had put themselves in… What they needed was merely a way to live long enough together to the point that they were trumping any and all other available avenues.Â

Useful Tool Alert!

Make every attempt to roll the dice with the biggest numbers.

That is what Hayne did; in grand scope Sam Black deck might have been “better”—at least for that one tournament before the greater flood of information was grandfathered onto every other less prepared player. Just last night I was discussing the possible futures of Innistrad Block Constructed with Jonny Magic.

Which side do you fall on?

JF: I am glad I don’t have to play this Block Constructed format. It is so dumb.

MF: Puzzling conclusion. You and your team did so great!

JF: But now everyone is just going to meta against our deck.

MF: I disagree. I think the format will shift more towards miracles, probably red miracles. They’re just going to make the mana work.

So…which side?

What changed between Jon’s triumphant umpteenth triumph and…tomorrow? The card pool didn’t change. What you can actually do in Innistrad Block Constructed didn’t change. The only thing that changed is the context of how information flows, who has it, and, subsequently, how it might be used.

Previous to Pro Tour Avacyn Restored only a small number of elite designers and teams had access to the best lists. I would actually argue that the best strategies were not ambiguous. Restoration Angel and Huntmaster of the Fells—the trademarks of Joshua Cho and Team SCG Blue—were known. Longtime Naya-phile Brian Kibler was singing to high heaven the virtues of Restoration Angel, while YT was pointing out that the card basically depicts “a dude looking up the skirt of a winged blonde in a Southern Belle nighty.”

The power of miracles was not ambiguous. Almost everyone I talked to pre-Pro Tour had Bonfire of the Damned very high up—maybe as high as Number One—in terms of new cards (and maybe Innistrad Block cards overall).

More than that, brewers and geniuses everywhere were talking about Miracles-linear. Surely an all-miracles deck would be powerful based on the performance of any and all later topdecks. Instant speed card drawing! Hallelujah!

Are high quality creatures like Invisible Stalker and Geist of Saint Traft some kind of secret? These cards have been dominating Standard for the entirety of the year 2012. Caleb Durward applied the card balloon pants to his Geists top make Top 8 of the last StarCityGames.com Invitational.

Not one of the powerful strategies was a secret.

Good lord! Tamiyo, the Moon Sage and Wolfir Silverheart were featured preview cards on the mothership!

What is more unbelievable than their eventual success is that tons of good players talked about how not good enough they were going to be all over Twitter. (Can I get a “good lord?”)

What differentiated the successful decks from the mere knowledge of what a particular deck idea might do was one thing: making the mana work.

Black & co. discovered a combination of off-linear Cavern of Souls + Abundant Growth as a major enabler. They could now apply Increasing Savagery to their hexproof U/W drop and had a better overall structure for winning Wolfir wars based on the tempo of blue spells relative to the ineffectiveness (for killing gigantic monsters) of red ones. What they played was not interesting, rather how they played them together.

The genius of Hayne and his Feeling of Dread was primarily in how he was able to solve a U/W deck when other teams abandoned it based on a perceived popularity of early rush. “Well, we can’t withstand early rush. Quit.” Rather, he “insanely” figured out how he might do that. He had the kingdom. Every single soul had the g-d kingdom! Team Mana Deprived, instead, discovered the nail.

Context, ultimately, is everything, in Magic and in life.

Tracing grain-lines across hardwood floors until your fingers blister.

Lining up every jar by size, in perfect, dust-free rows in your highest kitchen cabinet where no one—not even you (until next time)—will ever see.

Putting your lands in front of your creatures on the battlefield.*

“Obsessive-compulsive disorder.”

What we might vilify as an overwhelming impetus to rigor-without-value in some contexts, and some being extreme (OCD) are actually a very useful cluster of qualities when applied to others.

Example: The television show Monk was a critical and multiple award-winning comedic hit for the USA Network, depicting how a man with crippling OCD could actually be the world’s greatest detective.

Or… Isn’t someone with these kinds of “OCD” qualities exactly the kind of person you might want as your local nuclear power plant inspector rather than, say, Homer Simpson?

Finally, I think that contextualization in the “Who’s the Beatdown?” sense is actually the first—rather than the last—step in understanding the position and performance of a deck in the metagame.

Last week I took a little bit of flak in the comments of “Five Useful Instances of True Versus Useful” for what some (especially newer) players saw as a loose or dismissive depiction of The Rock. Now obviously it isn’t always wrong to play The Rock; as I said, I not only won the first ever Extended PTQ with The Rock, but playtesting with me Mike Pustilnik simultaneously won the first-ever Extended Grand Prix with The Rock (we were in the same room at the same time).

That said, it is still a useful rule to “never” play The Rock.

To wit:

In answer:

When I was sixteen, I was a fairly horrible driver. I remember one Sunday afternoon of cutting other drivers off with preemptive left-hand turns at stop lights, slowing down to a healthy 25 mph at crimson octagons, passing from the forbidden right wing, and various other clarion calls to gray hairs on my poor mother’s head…that resulted in an unending stream of, “Slow down!” “Stop!” and, “You are going to kill us!” all the way home.

Finally my mommy caught her breath, certainly long enough to conclusively chastise (and deservedly so) my wheelsmanship more when we finally stopped at home.

In answer?

(and flustered) “We didn’t get in an accident, did we?!?”

That we I didn’t blow up her Jeep Cherokee with all of us in it, resulting in a fireball of Floreses, was probably primarily due to the largesse of every other driver on the street rather than my own wanting execution.

Ever hear (disparagingly, in a gaming sense) of “results-based thinking?” That you won a single match with The Rock (or that I once won a PTQ with it) is as much a driver of the correctness of choosing it in the future as the survival of my family with me behind the wheel the next afternoon might be to my agile, “survived” Sunday piloting.

I kid.

Not really.

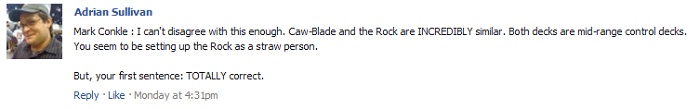

The real impetus of this article—and my devotion of some thousand words to context—was in response to a response by my onetime teammate and roommate Adrian Sullivan:

I disagree variously, but here, primarily on grounds of context.

Once upon a time I was (obviously) a big fan of The Rock. It was about the same time that the entire Pro Tour decided to all play The Rock, including Gabriel Nassif, who was at that point riding some “seventeen**” consecutive Constructed PT Top 8 run.

Variants of The Rock at that PT looked like everything from blue decks with maindeck Gilded Drake (Nassif’s) to anti-beatdown machines with maindeck Flametongue Kavu (the highest performing version at Top 16). Given its population in the tournament, zero Top 8 performances and such a hodgepodge set of builds, I later drew the conclusion that anyone playing The Rock in open formats moving forward could not possibly want to win.

Consider the context.

It was much the same as Pro Tour Avacyn Restored. Randy Buehler even pointed out the known-ness of Affinity as the Big Bad Wolf of Block and then Standard (Affinity would of course go on to win that Extended PT). There were 100 options…and these otherwise brilliant men chose…The Rock?

Let us apply the cost / value question of our veritable nail. Cost of a nail? A penny. Value of a nail? The kingdom.

Cost of a Gilded Drake? 2. Value of a Gilded Drake? Who the eff knows?

Against Gadiel it’s an 8/10, but against Pierre it’s a 2/10. Against Shuuhei a 1/10. I guess maybe if we play Gadiel every round?

Okay, let’s make it easier. A Flametongue Kavu?

Um… A six?

You sure about that?

Um… No?

Stop being so mean! We’re a bullet deck! We run on Vampiric Tutors! You of all people…

Yes, I of all people, know how to play [more than two] Vampiric Tutors in my “bullet” deck. And when you play for your bullet, you go and get an 11/10 and win the game on the spot. That’s the point. Tool: appropriateness, etc.

That’s the problem with The Rock. You don’t even know what your cards are worth. How can you tell how much they should cost?

I would argue that The Rock, when it was truly great (Grand Prix Las Vegas 2001), was a powerful threat deck. Spiritmongers cleaning up what Spike Feeder, Duress, and Pernicious Deed set up. I would put it—at that point—on the fourth most powerful strategy behind Trix (a favorable matchup), Tinker, and Goblin Recruiter. I lost to Tinker in the GP and Goblin Recruiter in the PTQ but beat everyone else. In later years people would actually start playing Goblin Recruiters in coherent fashion, i.e. “the Legacy format” (for years), but this was a new thing in 2001 (and thank God Mons was alone and ended up mana screwed in the Top 8). Tinker, of course, would eventually be banned, but at Las Vegas 2001 was considered—believe it or not—”a miser’s deck”; as such, its power was but rarely paired with a player of much quality. Like my not dying on that Sunday afternoon, my success with The Rock in that tournament on that day was largely a product of the kindness of strangers [in not playing decks that would annihilate me].

And the truth?

Our group didn’t have enough copies of Donate to all play the day I won the GP Trial, where I beat MikeyP and cemented my trip to Las Vegas. I had to play “the other” cards. That’s why I played The Rock originally. Nail: kingdom. Dominos.

When Miracle-Grow (and sickestever.dec) emerged later the same season The Rock moved well out of the Top 5 possible strategies on power level, and I would argue that it never recovered.

Now consider Caw-Blade. Caw-Blade is essentially three different decks.

- Caw-Blade in Paris

- Caw-Blade in the SCG Open Series

- Caw-Blade after the bannings

Caw-Blade in Paris was hands-down the most powerful deck of the tournament. I don’t think anyone has ever argued against this. It was so good that all the [ChannelFireball] Caw-Blade players rose to the top and eliminated each other, otherwise it would have been even more Caw-Blade dominance in the Top 8 (and there was plenty).

This Caw-Blade was the most powerful threat deck in context.

Unlike The Rock any time after Las Vegas 2001, this Caw-Blade knew what hands to keep. Its second turn was, in general, more consistently powerful than anything anyone else could ever do.

The notion that Caw-Blade at this point was a midrange control deck is almost laughable. It was a “Faeries” deck of the Bitterblossom variety more and most closely resembled full-on Necropotence (ultra-high quality shell with non-progressive self-contained card drawing engine)… You know, the kind that also had four copies of Demonic Consultation. Necropotence of this stripe was also the best defensive deck of its era; like Caw-Blade, it was both the beatdown and the control in multiple matchups.

Caw-Blade in the SCG Open Series proved itself to be arguably the greatest Standard deck of all time. This Caw-Blade enjoyed—and was simultaneously plagued by—shifting context. As many writers pointed out during its height, Caw-Blade was a deck at odds with itself, and the most successful players (at least before the advent of Exarch Twin) were primarily successful at the mirror match.

A Caw-Blade mirror was a fencing match. It was a duel of geniuses against idiots (don’t tell me you kept a hand with no Stoneforge Mystic or Squadron Hawk…) and ultimately a game of chicken between haymakers. The core plan of the Caw-Blade deck was haymaker-a-haymaker. My two against your two; my ability to withstand your Sword against your anticipation of shifting values in the mirror.

The best Caw-Blade matches I ever saw were Josh Ravitz beating an opponent who had out-Jaced him by five Jaces over the course of the match and Dave Shiels who cleared Phil Napoli board in a $5K Top 8 with a solo game 3 Day of Judgment, anticipating Phil would overcommit; Dave won through over 50 life points via playing something like three Batterskulls.

Neither of these matches had much to do with controlling anything. They were Tinker fights, more plan against fortune, the rewards of superior strategy.

After the bannings…well…I decided to play U/G Infect; so you know what I think about that kind of Caw-Blade. They let Valakut back in the metagame WTF?!?!

I would ultimately argue that Caw-Blade resembles The Rock not at all. In terms of classic archetypes, The Rock is a midrange hodgepodge that can have elements of ramp and board control but is saddled by a hundred maybe relevant support cards; Caw-Blade, on balance, is an ephemeral wisp of Tinker (via Stoneforge Mystic), Faeries-style aggro-control, Faeries-style True Control, and Necropotence. That Caw-Blade—like The Rock—can also mold its game plan to the opponent’s plays is more a testament to its monolithic pedigree and Swiss Army Knife-like array of card advantage-fueled options than any true similarity between the two decks.

One is a deck with A Plan (and more than one).

The other, A Streetcar Named Desire.

LOVE

MIKE

*LOL

**”seventeen,” also “LOL”