“The history of the first five years of the Pro Tour can be summarized as only one player playing the game the way it was supposed to be played; the next five years are a series of attempts by the rest of the world to catch up to Jon Finkel.”

Let me tell you about my first hero in the world of Magic: the Gathering.

He was the first United States National Champion whose name I knew. I saw his use of the Whirling Dervish in the Top 8 of those Nationals when the rest of the tournament was filled with super cheesy Hymn to Tourach decks. When the first Magic: the Gathering Black Lotus Pro Tour event changed the world in the snow-covered avenues of New York, New York, once again it was this player who stood in the spotlight of the Top 8. He had a different deck – “The Justice Deck,” we called it, squeeing like the little circle of pre-Pro fans that we were.

This player? We worshipped this monolithic weaponeer – and best player on the planet — known as Mark Justice.

I can’t say for certainty what attracted our pre-Professional – albeit talented — group to this player. For certain, we became enamored with “The Justice Deck” despite the raging Swamps and fetid stink of Necropotence all around the Pro Tour Qualifier circuit. Rob Hahn’s Qualifier win for the first Pro Tour: Los Angeles was with a sixty-four card, twenty-one land rehash of Justice’s deck – albeit sans Elkin Bottle. This was an affirmation of our suspicions: “The Justice Deck” could beat Necropotence decks.

Altran was the first in our group to have any success on the Professional level. He was probably the most talented among us. Al learned his lesson at the 1996 Ivy League Championship tournament after Tony Tsai “Pyroclasm’d his Fellwar Stone” (and ask me about that story another time). Al then began piloting his own copy of “The Justice Deck” and flew it to a U.S. Nationals invitation. In the muddy haze of the Black Summer of 1996, who but Altran would play “The Justice Deck” at Nationals? Not Mark Justice, certainly; Like so many other Pros, Justice had gone to The Dark Side, and was playing the hated Black Deck.

By the time I played in my first Pro Tour four months later, Justice was once again on the Red and the Green. But by then, the glamour was gone. I latched onto other heroes that weekend – but that’s also a story for another time. Today’s tale is about Mark Justice himself.

Let me take you back to the semi-finals of the 1996 Magic: The Gathering World Championship. This event took place between my and Altran’s first Pro Tournament appearances.

The Stage:

Top 4 of the World Championships.

The Opponent:

Batting average Mega-maven and “Littlest Viking”, Olle Rade.

The Matchup:

Olle’s G/W Armageddon deck against the much-hated Necropotence deck, piloted by Mark.

The Game:

Game Four – A comedy of errors… at best.

“Today, even spitty (the real word rhymes with “spitty” – michaelj) players talk about how to beat Gaea’s Blessing with High Tide.”

–Brian David-Marshall

Picture this: Going into Game Four, Justice is up two games to one and is a lone game away from the making the finals. Mark sides in all his Dystopias and Contagions. He leaves multiple Shatters in his deck… This seems odd to me, because over the course of this game, he lets Rade sit on a Zuran Orb forever.

…But I’m getting ahead of myself. Suffice it to say that these choices left Justice tellingly light on offense.

Rade begins the game, and opens with Forest and Llanowar Elves. He has no second land — there was no Paris mulligan rule yet, and so Rade was forced to keep a one land hand, like it or not. Like a true Pro, Mark has the Strip Mine for the sole Forest, and is not afraid to use it. Olle plays no land on the second turn, and brings it with the Elves.

It’s turn 2: What should Mark’s play be?

Olle Rade’s Board:

Llanowar Elves (tapped)

Mark Justice’s Board:

Nothing

Mark Justice’s Hand:

Dark Ritual

Dystopia

Necropotence

Serrated Arrows

Ebon Stronghold

Sulfurous Springs

Swamp

I think that there are many possible plays here. Mark could run Dark Ritual to cast Dystopia. He would lose card advantage in the short run, but it allows him to kill Rade’s only mana source, plus it saves him some damage from an attacking Elf. Another possible play for Mark is to Ritual out Necropotence, but this isn’t optimal yet.

Justice does neither of these. Instead, he makes a defensible, conservative play of Ebon Stronghold.

On the subsequent turn, poor Olle again fails to draw a land. He attacks, bringing Mark down to eighteen life. Mark draws Mishra’s Factory from the top of his deck.

Olle Rade’s Board:

Llanowar Elves (tapped)

Mark Justice’s Board:

Ebon Stronghold

Mark Justice’s Hand:

Dark Ritual

Dystopia

Necropotence

Serrated Arrows

Mishra’s Factory

Sulfurous Springs

Swamp

Justice makes an intuitive play — he plays Swamp, Dark Ritual and Serrated Arrows, and bins the Llanowar Elves immediately. I am fairly certain the land drop was correct given Mark’s hand, and I am completely sure that Mark is correct in killing the Elves immediately. So far, so good.

But what about the next turn, after Rade fails to draw a land for a third turn running?

Olle Rade’s Board:

Nada

Mark Justice’s Board:

Ebon Stronghold

Swamp

Mark Justice’s Hand:

Dark Ritual (just drawn)

Dystopia

Necropotence

Mishra’s Factory

Sulfurous Springs

There are two reasonable plays here. Justice can play Sulfurous Springs and cast Necropotence — though he would take a point of damage to do so (which, given Necro’s “pay a life to draw a card” effect, roughly translates into the loss of a card). He can use Dark Ritual to play Necropotence, which allows him to play the Mishra’s Factory on this turn, plus avoid the damage from the Springs. However, I feel that the second play is inefficient in terms of both mana and cards. Even if Mark loses a card by taking a point from the Springs, the Dark Ritual is much more valuable as a late-game commodity to power up a massive Drain Life. Plus, the former play maximizes the use of Mark’s in-play resources, whereas the latter play does not.

Inexplicably, Justice chooses neither of these options. Instead, he sacrifices the Ebon Stronghold to cast Necropotence, and plays Mishra’s Factory.

Break the Ebon Stronghold? Are you kidding me? If he were dead, Erik Lauer would turn over in his grave. Why would Mark throw away his lands when he’s already in a position to cast Necropotence? This error is made even worse by the next turn – Mark plays a Swamp and Black Knight (both drawn off Necropotence). He leaves himself unable to activate the Mishra’s Factory, and passes the turn without dealing any damage!

A few turns pass, and Justice is unable to finish off his mana-screwed opponent, as he has left himself with such an offensive-poor deck. This gives Rade time to draw a land, enabling him to cast Land Tax. Again, Justice makes a huge mistake — he refuses to immediately play Dystopia, which allows Rade to draw six big lands with Land Tax instead of just three. This comes back to haunt Justice just a few turns later, in what turns out to be the pivotal turn of the game.

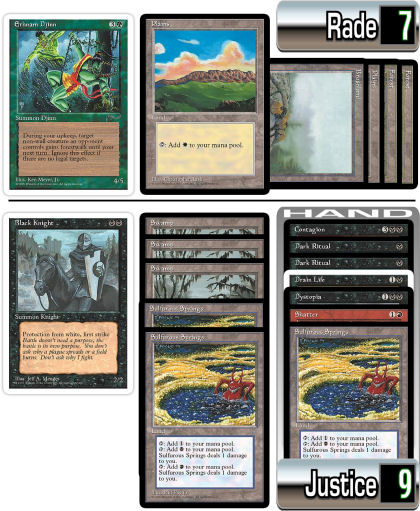

Olle Rade’s Board, at seven life:

Erhnam Djinn, Plains, Brushland (tapped), two Forests (tapped), Plains (tapped)

Mark Justice’s Board, at nine life:

Black Knight, three Swamps, two Sulfurous Springs

Mark Justice’s Hand:

Contagion

Dark Ritual

Dark Ritual

Drain Life

Dystopia

Shatter

Sulfurous Springs

With Rade at seven life, Justice’s play is academic. He taps his three Swamps and two Sulfurous Springs, plays both Dark Rituals, and aims a seven-point Drain Life at Olle’s head. Rade responds by tapping his Plains to calmly Swords to Plowshares his own Erhnam Djinn.

But wait!

Doesn’t Mark still win the game? Shouldn’t the best player in the world simply Contagion the Erhnam Djinn in response (removing Dystopia from the game), so that Olle gains no life?

Yes.

Why yes, he should.

And no – he didn’t.

Instead of dying on the spot, Olle is left at four life. Mark swings for two with the Black Knight, but Olle follows up with a second Erhnam Djinn, which holds off the Black Knight for a turn. Olle is forced to give Mark’s Black Knight Forestwalk, and can only swing for seven (thanks to Giant Growth) the turn before he dies. Rade had just drawn a potential chump blocker, meaning that if the Black Knight had not been given Forestwalk, it’s likely that Justice would have lost this game, and would not have advanced to the finals of the World Championships.

Not that he should have, anyway.

This, ladies and germs, is a man who was considered to be the best player in the world. Not “one of the great players,” but The. Best. Mark had an impressive resume before the 1996 World Championships, and he added multiple Pro Tour Top 8 finishes afterwards. And yet, I am sure that you or I could probably have played this (successful, despite Mark’s play) Top 4 game against Olle Rade with one thousand times more skill than Mark.

To be fair, Mark wasn’t actually the best player in the world. That honor fell to the man who finished ninth at Worlds that year. I’m sure you know his name.

I am not recounting this tale to bag on Mark Justice (though in revisiting this Top 4 match, I received a virtual splash of cold water about the face similar to the one I experienced when watching “The Return of Optimus Prime” at age twenty-four). Instead, I want to talk about contrasts, and about evolution. Randy Buehler and I spoke a few months ago, and he claimed that it is harder to qualify for the Pro Tour now than it was to win at the Pro Tours of distant past. I didn’t believe him at the time… But he must have, however, been right in retrospect.

The overall skill level in the game is so much higher now than it was in 1996 that it’s not even interesting to compare the stars of today to the stars of yesteryear. Star Wars Kid analytical capabilities and skill at stack decision-making wow me. In what should be an autopilot deck, he can fight through seemingly unassailable situations and come out victorious. I’ve seen him battle through Orim’s Chant and multiple Counterspells to win — and this is in games against the best Extended players in the world.

Up until Los Angeles, no one would have thought of Star Wars Kid as more than a high-level Pro Tour Qualifier player. And yet, he is many times more skilled, and has a more intimate knowledge of the game, than a player like Mark Justice — a player who at one time had multiple articles dedicated to declaring just how unstable he was.

Randy was definitely right.

What does this mean?

It means that Billy Moreno certainly isn’t the close to being the worst player of all time. He isn’t the worst player to make it to the semi-finals of a Pro Tour, or to even make the Top 8. Yes, Billy played pretty sloppily in the Top 4 of the most recent Pro Tour: Los Angeles. Compared to Mark Justice at Worlds in 1996, Billy is Pele in his prime. I can tell you from firsthand playing experience that Billy has a superb analytical mind. He commonly sees moves during Constructed playtesting that even I miss.

Everyone is human. Justice was still one of the Pro Tour elite in his day, regardless of how badly I am characterizing his play in the match against Rade. This does not mean he was flawless; Even with all his mistakes, including giving up three extra cards to Land Tax, blowing an on-table kill, dropping the wrong land, sacrificing a land needlessly, missing an attack, and managing his mana horribly, he still retained his composure during the endgame. He saw his opening when he needed to, and didn’t needlessly spend cards or life on victory. Eric “Danger” Taylor told me that he appreciates players like Farid Meraghni or Tim Aten — players who do not lose their composure after making mistakes. Those two could pull out a win by keeping their cool, whereas others might have fallen apart. Justice’s last two turns were tight (except for the Contagion), and mentally speaking that made up for a lot.

Qualifying for the Pro Tour is hard. I know this, the newly-qualified Richard Feldman knows this, and you should know this. It takes years for some players to qualify for the big show.

Chin up, Qualifier regular!

You’ve got the skills to be a Magic World Champion.

Love,

Mike

Bonus Section

Here are some stories of other mistakes I’ve witnessed, presented for your entertainment.

In the finals of Pro Tour: Columbus, Sean Fleischman was allowed to make timing errors that wouldn’t fly at Friday Night Magic today, much less at the Pro level. He played Pyroclasm, resolved killing half of the creatures on the board, then inexplicably resolved killing the other half of the creatures on the board… And then picked up his own Blinking Spirit! They might not have invented “the Stack” back in the day, but even loosey last-in, first-out wouldn’t swing it that way.

Tom Chanpheng, the 1996 Magic World Champion, beat Justice with a White Weenie deck. It was a special White Weenie deck though. Tom played with several Protection from Black creatures and Sleight of Mind… But forgot to add any Blue sources of mana to his deck! He had midgame mulligans half the time… But at least it was easy for him to sideboard.

Last month, arch-mage Kai Budde tried to run Forbid in his Extended deck at a Grand Prix. He was forced to replace it with a basic Island.

What was the worst mistake I’ve ever made? I think it was an error which occurred during the first round of a Masques Block Qualifier. My opponent was Sean McKeown: He was running a Rising Waters deck whereas I came with Mono-Black Control. I lost the first game in this horrible, horrible matchup but had a definite plan for the second and third games. I was running four Cateran Summons, so my sideboard plan was to Tutor up a lone Silent Assassin so that I could get my beat on bear-style.

I was so excited to see the Cateran Summons in my opening hand in game two that I did a lap around Neutral Ground. I smugly played the turn 1 Summons for my big second-turn Assassin.

The mistake?

In addition to the Cateran Summons, my opening grip included both Dark Ritual and Chilling Apparition. Sigh.