While I was busy sitting on the sidelines, breaking Standard, the actual keynote Standard event of the moment was still taking place. Madisonian Jasper Johnson-Epstein was resting in preparation for his Top 8 match in the StarCityGames.com $5000 Standard Open in Indianapolis. I was sitting at 6-3 with my update on Chevy Elves (the deck that gave Sam Black his U.S. Team Member status), out of contention of any real prizes, and reflecting on the event. I really loved my deck, and the metagame, as best as I could tell, looked about what I expected it to be.

In many ways, this event is the premier event for Standard that we’ve seen. Ten rounds of Swiss is a lot of rounds. The attendance in Indianapolis fit into the scope of some of the smaller Grand Prix. Unlike the mess of data we have from Kyoto, our first dual-format Pro Tour, Indianapolis would be all one solid format. This means that none of the problems that plague analyzing Kyoto are there. Decks were actually pitted against decks with similar records, as compared to, say, Shuu Komuro’s experience playing against great drafters with mediocre decks on Day 2. Even when corrected for by a rudimentary analysis scheme like opponent’s strength, as I did for Kyoto, there really wasn’t a thing you could do about the shakiness of the data. The best you could say is, “Well, based on what little data we have, there is evidence to support X.” Not exactly enticing.

Looking at a Top 16 really isn’t that much help, either, though. If you really, really do your homework, and you examine the “virtual” Top 16 (including Alex Froerer’s Fish list), you would have the following information:

432 Players, won by “Sunburst Rock” co-creator Robert Graves, playing Five-Color Control

[Deck Name]: Top 8 count / Top 16 count* (including 17th place, tied for top 16)

Five-Color Control: 2 / 1

Tokens: 2 / 0

Vengeant WW: 1 / 3

Faeries: 1 / 1

Green/White: 1/ 1

Boat Brew: 1 / 0

Doran: 0 / 1

Fish: 0 / 1

This almost seems like a reasonable bit of data. Sure, we don’t know exactly what else was there, but it looks pretty good, seemingly representative of something similar to what we saw in Kyoto.

Obviously, though, there could be a deeper picture.

StarCityGames.com Jared Sylva walked over to me to let me know that the decklists could be available for review. After retrieving them, a sheaf of over 400 papers of people’s hopes and dreams, I realized that I had in my hands the actual Standard metagame. Once you get to a certain critical mass of decklists, it can almost be overwhelming in cataloguing to any real satisfaction. Armed with the information provided me by Mr. Sylva and Mr. Hoefling, I realized just how much better our understanding of the format could be.

Wizards had their own analysis of the “Top 8” decks from Kyoto, an analysis that is, among other things, demonstrably wrong, using the tie-break methods of the event itself (OMW% as the first breaker). The actual Top 8 looks something like this (from my earlier data-mining):

1 Vengeant Weenie

3 Boat Brew

2 “Doran”

1 Elves

1 Five-Color Control

(Those two Doran decks could be best further broken down as Doran and Dark Bant, if you prefer.)

This isn’t too different from the information from Indianapolis, and Indianapolis is clearly informed by these results: Graves list is, despite its departures from Nassif’s list, still very similar, and the most represented list in the Top 8, Vengeant WW, is likely influenced by the clear domination of the Swiss by Cedric Phillips list for Kyoto. Where the surprise of Kyoto was likely the strong representation by Black/Green/(x) decks, the surprise from Indianapolis was the pair of very different Green/White lists, Joshua Scott Honigmann’s Martial Coup/Overrun deck, and Stephen Addison’s Wilt-Leaf Aggro deck. I’m sure that tons will be said about these deck decks in the next weeks; I’m going to focus on looking at the big picture.

If you only looked at the Top 8 of Kyoto, you might have expected that the field was over a third Boat Brew. You’d have been incredibly overestimating Boat Brew in the metagame (and underestimating its actually EV in the field). Similarly, just the Top 16 of Indianapolis might lead you to conclude that Vengeant White Weenie was something like 25% of the field. The actual field looked like this (for decks with 3 or more players):

Five-Color Control: 65

Faeries: 46

Boat Brew: 36

Blightning/Red Burn: 34

Tokens: 33

Dark Bant: 26

Vengeant White Weenie: 26

EsperLark: 18

Bant Aggro-Control: 17

Green/White: 14

Mono-White Weenie: 13

Planeswalker Control: 10

Jund Ramp: 8

Elf Beatdown: 7

Swans: 7

Blue/White Control: 6

Elves!!!: 6

Merfolk: 6

Tezzerator-Control: 3

Stoken-Tokens: 3

Doran: 3

Zoo: 3

Quillspike-Combo: 3

Turbo-Fog: 3

Other: 36

Here’s one of the first things that come to my mind:

“Wow, Standard is abundant with decks.” And many of these decks are very, very good. Still, there is much more work to be done. Grabbing my five pounds of decklists, I waded into them to see what only the Top 64 looked like. (Yes, this took a little bit of time). If we were to re-write this list, above, with only those decks that had representation in the Top 64, it would look like this:

5-Color Control: 65

Faeries: 46

Boat Brew: 36

Blightning/Red Burn: 34

Tokens: 33

Dark Bant: 26

Vengeant White Weenie: 26

Esper Lark: 18

Bant: 17

Green/White: 14

Planeswalker Control: 10

Jund Ramp: 8

Elves Beatdown: 7

Merfolk: 6

Stoken Tokens: 3

Doran: 3

Zoo: 3

Bloom Tender Control: 2 (out of the “Other” category)

So, if you’re only concerned with decks that “win,” you’re still talking about eighteen archetypes. That’s a damn lot. The most represented deck, Five-Color Control, sat at about 15% of the metagame, followed by Faeries at about 11%, and Boat Brew, various Red decks, and Tokens at 8%. This kind of diversity speaks well of the format, but also says something about the foolhardiness of deciding to “just beat Faeries and Boat Brew,” for example.

A lot of times, when people look at formats, they remember those formats that are deeply overwhelmed by an archetype. Block Faeries, for example, had a huge portion of the field under its sway. These formats can dwell in our minds, so when we think of “Deck X” as enemy number one, we imagine an enemy as ubiquitous as Block Faeries or Disciple/Ravager Affinity. Healthier formats don’t look the same. It’s all too easy to get stuck in the trap of deciding that you “only” need to worry about some archetype you imagine is going to be deeply common.

There are still some clear flaws to the data. Because there was no real incentive to continue playing (aside from the small amount of ratings points), a player like Gerry Thompson might start out weak (1-2) and simply pack it up for the day. Had he continued, I’d have been unsurprised to see him pick up anything from 5-2 to 7-0 for the remainder of the day, placing him in the Top 64 or better. But because he didn’t, we have a data set that is encumbered by more drops than we might have seen in a Grand Prix or Pro Tour. What we get, then, is a collection that is heavy on the die-hards and those that are in the running the whole way.

If we think, then, about the 357 people playing archetypes that were represented in the Top 64, we might have a better sense of what we should expect to be playing against if we are doing well in a tournament. There is a lot to be said about the phenomena of “the Jungle” that exists in metagames (see my article Game Theory — The Marketplace for more), but if you’re playing in a tournament with a hope to win the whole shebang, it doesn’t necessarily serve your time that well to play against all of the decks that could show up, so much as to spend your time against the winners. Playing against Esper-Lark for playtesting might seem like a waste of time if you imagine it as 4% of the field, but it looks a little more important when you realize that it was played by 5% of the “represented” field, and even more when you think about how top-heavy the deck swung.

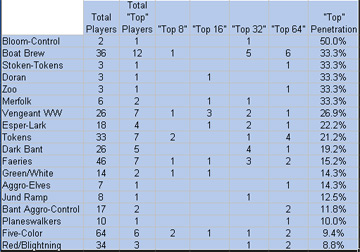

Check out the following table, which further breaks down the results from the event.

A lot of things can be gleaned from this, if we think about the data at large.

First of all, one of the most stark things of note is that all of the combo-based decks couldn’t make it. Swans was represented the most, played by several talented players, but it just didn’t make the cut.

The next, and to my mind, most notable thing, comes in looking at White Weenie and Vengeant White Weenie. Between the table and the archetype listings, above, we can see that Vengeant White Weenie was the most abundant deck represented in the Top 16, despite having only 26 players playing it. 6 of the 26 playing it made Top 16. Also amazing, though, is that none of the 13 players playing mono-White Weenie made Top 64.

Of course, there is also a lot of “noise” in the data. Take Doran, for example. Three people of the 437 played the deck, and one of the made Top 16, our own Patrick Chapin. What does this incredibly small sample say, then, about the value of Doran? The deck could very well be great. Our data is so small, though, that it is hard to know. Is “Bloom Tender Control” better because it had only two people playing it, and thus was better represented than Doran? Clearly, we should pay attention to these decks, but not lose sleep over overlooking them.

Here is Chris Woltereck version of Bloom Tender Control (astute observers will remember Chris from his StarCityGames $5k win with Five-Color Control):

Creatures (23)

- 2 Seedborn Muse

- 4 Mistmeadow Witch

- 4 Mulldrifter

- 2 Sower of Temptation

- 4 Reveillark

- 4 Bloom Tender

- 3 Glen Elendra Archmage

Lands (24)

Spells (13)

Cool deck. But not something you want to spend a lot of time testing against… At least not yet.

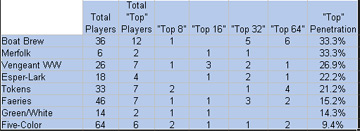

If we cut it down to those decks with at least 1% representation in the “represented” field,” and with a player in the Top 16 (or better), you get the following:

Here, we can see that, just as in Kyoto, Boat Brew was the deck to play if you wanted to do well overall. An astounding 33% of players playing Boat Brew ended up in the Top 64. Interestingly, if you take “Brian Kowal’s” build of Boat Brew from Kyoto (zero Ajani Vengeant), you have something even more incredible: all four players playing it made Top 64. 100% penetration. Holy *%&#.

Now, stats like that can be misleading. Three of the players were from Madison, where Brian Kowal lives, and one of those was Brian, and the other two are at least seasoned tournament players. If we were to only use the data from the 437 who were seasoned players, I’m sure that that data would skew higher towards wins, as well. While this archetype “only” had a single player in the Top 16, its twelve finishers in the Top 64 is shockingly impressive.

Vengeant White Weenie, in many ways, might have been the deck of the tournament despite this. Its penetration number is not that far behind Boat Brew, but it is far more impressive in its Top 16 finishes than any other deck, with fully 25% of the Top 16 made up of Vengeant White Weenie, despite the deck being only a mere 6% of the field. Either way, it remains worth of note that collectively, Windbrisk Heights, Path to Exile, and Figure of Destiny, supported by Red, was easily the most dominating set of decks of the day.

Also interesting is the relative success of Merfolk. None of the Fish decks shared a common build. One was a Chameleon Colossus-based deck, another was almost a hybrid of Richard Feldman list with Adam Prosak, and there were others, besides. Still, a 33% penetration is very impressive for a deck that was presumed killed off as collateral damage in WotC’s war with Faeries. I guess Volcanic Fallout doesn’t execute this archetype after all!

Esper-Lark seemingly comes out of nowhere. While Irvine has long been championing this style of deck, it hasn’t seemed to get all that much attention. Its top pilot, Grand Prix: Chicago Top 8 competitor Tommy Kolowith, finished in the money with the deck, and with so few people playing it, getting four people into Top 64 is quite impressive.

Tokens, of course, shares with Five-Color Control the distinction of being the most represented decks in the Top 8. It put up an impressive 21% penetration into the Top 64, behind many of the other archetypes, but by far ahead of Five-Color Control, which put up a paltry 9%. For Five-Color Control, this is almost embarrassing. The deck, at large, performed so badly overall that I can only imagine that it suffers from the common problem of overexposure: people who aren’t good enough to be playing it are playing it anyway, and the players who are good enough to be playing it are doing well, while the rest fall. Tokens, on the other hand, found itself represented throughout the top of the field, not because of the brute force in numbers that Five-Color has (with its player count at double that of Tokens), but from simple success.

Faeries represented itself adequately at the event. If you count its numbers from the “representative” field, it just barely outperformed what a deck might if it is average. As the second most popular deck in the field, this goes a long way to saying that perhaps this was not the deck to play. It’s not that the deck is bad, it just appears that, at least right now, the format is hostile enough to it that it is being held down, and that other decks are simply not being restrained by the format, and are simply better, pure and simple, right now.

Green-White is the odd one here. Both of the decks are vastly different from the Top 16. One is basically a mid-range deck, leaning slightly to control, and the other is a balls-to-the-wall aggro deck. My gut tells me that there is a lot of room here for both of these decks to exist, and that it is likely that the rest of the Green-White decks are simply so different than these two, grouping them together doesn’t do them justice. I haven’t had time yet to try these decks out, but I’m willing to imagine that they might both yield some very interesting fruit. Their numbers either look weak, when compared to the other competitive decks, or ridiculously incredible (if we imagine the other decks as “not really” the same as this deck). A quick glance at some of the other Green-White decks confirms that the lists are only vaguely alike. With so few instances to go with, the standard deviation on these decks essentially places them in the same “noise” space as Zoo and Stoken Tokens (updates of Stuart Wright fantastic Furystoke Giant deck from PT: Hollywood).

I think the coolest decklist I saw looking through all of the lists has to be this one: “Rad Nauseam” designed by Josh Knaack, Ryan Seymore, and DJ Kinselman. Joshua didn’t do so hot with it, but I’ve definitely managed some cool kills with it in a few games. Maybe, right now, cool isn’t good enough, but it’s still interesting to think about. Here’s the list:

Creatures (10)

Lands (37)

Spells (13)

Sideboard

As for me, I’m still plicking away at those last two PTQs. If at first you don’t succeed!

See you next week…