This Pro Tour featured two new formats, not one. If you count the Pro Tour Players’ Club, it had three. The Club is wonderful, the Block format is good. The new tournament structure is an unmitigated disaster. I will be talking about all of them. First, the best news of all: the Pro Tour Players’ Club

All of Nothing

The Pro Tour Players’ Club is the best thing to happen to Pro Tour players since the Pro Tour. The increased payouts and then the Masters series and end of year payouts were attempts to let players make their living professionally, and they served as stopgap measures that let the top players put food on the table barring huge numbers of illegitimate children. The problem was that one by one many of the players realized that they had developed highly valuable skills on the Tour and that they were highly intelligent people who could do a number of other things for a living that paid a lot more money. Most of us still love to play, but you end up spending lots of preparation time and often coming home with nothing. When you win it’s a good deal but unspectacular, and when you lose it sucks.

The Club changes all that. The first thing it does is increase the benefits at the high end and increase them drastically. At the higher levels you get an amazing benefit package that is worth shooting for. It’s not going to get you a call from David Williams’ investment broker, but going to Grand Prix at hundreds a pop is very cool. By taking away the expenses and giving you guaranteed income, Wizards has made the worst case scenario acceptable. That’s huge. Even as low as level three you can attend a Pro Tour without worrying about going home with nothing.

Do not underestimate the impact of treating your players right in the little things. The players’ lounge is a trivial expense, but the players love it. [The food supplied there seems to be deteriorating though – not sure why. – Knut, who agrees with Zvi] Providing us with our basic equipment is another big boost – if somehow our cards could be provided for Constructed events and playtesting, that would be a huge benefit. If the cards had a gold border, it would be even crazier, and Wizards already distributes sets due to the Magic Online redemption program. Now they’re saying that they understand how frustrating the Tour can be and that they want us to come home feeling good. I could brainstorm all day about good ways to add to the system, but this a great start.

The feature that perked my interest the most, naturally, was the Hall of Fame. If I were to be entered into the Hall, which would be an honor in and of itself, I would then have permanent invites to all the Tours and get five hundred dollars for attending. I can’t see turning that down on tournaments in the United States and if I didn’t mind the format, I’d likely go to Europe as well. Japan would still be tough because it costs so much and wrecks you for a week. I love Japan – it’s just not an easy place to visit. Once I was going, I’m sure I’d be roped into testing. Star City’s loss could be one team’s gain – and this time I’m betting TOGIT at least bothers returning my messages. [Considering you had most of the good decks on your own, I’m betting most teams would be interested. – Knut] I have no idea how the Hall of Fame is going to work, and if I did I wouldn’t spill the beans, so I’ll be watching along with everyone else.

That brings me to the topic at hand: All or Nothing. Feel free to skip ahead if the math doesn’t interest you. What I mean by that is that Magic at the Pro level has always been an all or nothing proposition, but now it is even more of one than it was before. The reason for this is that the marginal value of performance goes up as your performance improves, both in any given tournament and overall. Within a Pro Tour, everyone knows this. The semifinal match you win is worth more to you than putting up a perfect record on Day 1. The difference between first and fifth is much bigger than fifth to last. A good rule of thumb is that each win tends to double your winnings… or better. Working hard to get to the Top 64 is a lousy money deal, if a fun one. The extra work that moves you up the chain from there is time well spent. From the perspective of what Zaphod calls the fame and the money you do the early work not for its own sake, but in order to be able to keep going.

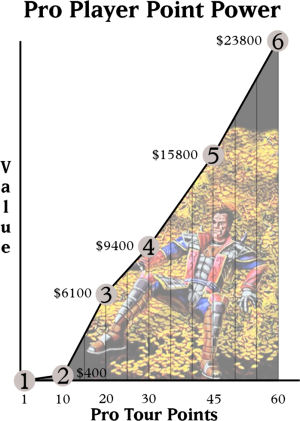

Now look at the marginal value of Pro Tour points. In effect there are five points that matter: 1, 10, 20, 30, 45 and 60. No other points matter, and the first point is essentially negative if you’ve never had it before because you give up valuable amateur status. Level two has its benefits, particularly the national championship. The second bye shouldn’t be too difficult to earn for good players and it also should normally be moot because travel to a Grand Prix out of your driving range requires three byes to be worthwhile. That could change if you’re shooting for the top of the club, as you’ll see, but you have to think you’re very good. Those tournaments just got a lot harder. Let’s estimate the cash value of level 2 as $250 for the invitation and another $150 for level 2 byes at all GPs. That combines to $400, which is nothing to sneeze at, but similar to winning a PTQ.

Level three is the first highly valuable level. Players have shown a willingness to give their opponents all of the money at a $500 PTQ in order to take the slot, even if they have to give up the right to play in additional PTQs and deal with the taxes. An invitation can be valued at the prize pool of the tournament – including Pro Tour points – divided by the number of players. The cash let’s say is worth $666 for each of six tournaments, since money is the root of all evil and man needs roots. You can expect to average four PT points. Reduce all benefits by about 25% because you give up the chance that you would have qualified in another way, so that’s worth $500 and three PT points. Note that those points are more valuable than they look because they come in bunches which increases their value. You also get the $500 for showing up. So that’s worth $5.5K and 18 points. Now we need to estimate the value of the GP byes. Discounting for the fact that your rating could have earned you the byes anyway if you’re good enough, but that this cuts you off from playing tournaments for fun, I’m going to say that the byes are worth $100 per tournament that you have the option to attend. You’re still stuck in the USA, so let’s say $600. This package is therefore worth $6100 and 18 Pro Tour points.

Level four adds $500 a tour and airfare to or from Japan. That’s what free airfare to one event means. Calling the Japan package $800, you just picked up $3300 extra for $9400 and 18 Pro Tour points. This is less valuable than level three, but you’re likely also earning end of year payouts at the same time.

Level five adds another $3000 for attending the tours and free airfare to the other five events. Let’s say you live in the USA, and that all but one of these events is domestic. That’s $250 an event plus $400 for Europe. What you could have saved by shopping around you save in time and aggravation because you didn’t have to. This is now worth $13800 and 18 Points, but now you need to add the GP appearance fee. For now, let’s say that you were going to six domestic GPs before, so you pick up $1500 for doing what you were going to do anyway. It wouldn’t be unfair to now add two more events, giving you $2000, and we’ll cancel out the other benefits and costs of those events to save time. Let’s call this package $15800 and 18 points.

Level six is another $3000 for showing up at PTs and free hotel. Wizards giving you a hotel means you get a good hotel, so let’s call it $75 a night to cover replacement value for three nights and two extra nights at Worlds. $1500 in hotel rooms is neat. Now the $500 a Grand Prix is another $2000, but it’s more than that because you can now go to Europe. Let’s say that European GPs would have been a $250 loss before, so they’re worth $250 each for another six events and another $1500. That makes the value of this package an amazing $23800 and 18 points. Assume for now that there will be some additional value in the PT player of the year race.

That looks roughly linear, with the points directly before 20 the most valuable and others less valuable but still worthy until after you pass 60 and enter the PT Player of the Year race instead. In effect, 60 points are worth $24K and 20 points are $6K. If you get twenty, they hand you fifteen back for next year, making that $6K persistent over time since anyone who cares at all can find a way to turn that into twenty. If you can’t, you’re not getting the benefits of the slots anyway. A rough translation would now indicate that a Pro Tour Point is worth 24K/60, or $400. However, the marginal benefit of gaining a point is more than that because any point you gain is unlikely to be one of the early points that gains you nothing. You also factor in the fact that points beget points and it’s hard to argue they’re not worth $500. That number is conservative.

Now look at what happens when you fly out to a European GP. Say you have three byes, but no appearance fee right now. However, you will average $500 in expenses, $125 in prizes (for a good 3-bye player that’s reasonable – the giant nature of Euro GPs screws up the expected value you’d receive) and one PT point. That’s certainly a conservative estimate for a good player. You’re now ahead by $125! That’s not a bad European weekend of gaming. Now you need to re-evaluate every step of the benefits, because your ability to travel to events is far better than it looked like before. It adds value to every level of the structure, which in turn cycles back to give even more value. What enables all of this is the dream of hitting 60 points. There are a lot of fixed costs in Magic: Being good at the game, staying sharp, maintaining a collection, maintaining a Magic Online collection, keeping a team together, choosing a job with flexible hours, keeping up with Magic strategy, supporting your local store and many things I’m probably not thinking about. The middle path leaves a lot of value on the table, because a lot of the value of the points presumes the full path.

Tournament Structure: A Failed Experiment

You can’t blame a guy for trying. That’s not true, because you can blame anyone for anything and in this community it happens daily… but you would be incorrect to do so. I applaud Wizards trying to mix things up and give a shot to a new structure. When I first saw it I thought it looked like a good idea at the time. The problem is that it doesn’t work, and the more I analyzed the structure the less I liked it. When the tournament was played it became clear that it is not a viable option. There were several problems that I would consider deal breakers.

Good News 1: Every Match Counts

If you’re not playing for money then you’re not playing at all, which keeps the tension high and people alert. There will be no slackers here and no players forced to play it out to try and pick up an extra point. That is very cool.

Good News 2: Less Work to Run

Let’s not kid ourselves, the fact that the field starts shrinking in round three and keeps shrinking makes this type of tournament much easier to oversee. There’s also no worries about intentional draws or other such nonsense. Everyone must play to win.

Good News 3: Slow Play is Punished

If you draw, it’s a complete disaster, which makes me happy.

Good News 4: Most People Get Something

This is similar to the club. Seven players out of eight in the tournament will win at least a hundred dollars.

Good News 5: No One Big Cutoff

The problem is that the bad news more than makes up for this.

Bad News 1: Not Enough Rounds

Right now this is the big one. This could be fixed, but twelve rounds are not enough to choose a Top 8. I am not taking away anything from those who made it, but it’s just not enough for a field this big. There’s a reason we went to fifteen or sixteen rounds for most Tours.

Bad News 2: Byes to… Winners?

I don’t understand this at all. It shouldn’t take much math to realize that when you give a bye to someone who has a winning record, you injure all the other players in terms of expected value. The later in the tournament it happens, the worse it gets. Gadiel Szleifer got a bye directly into the Top 8! Early wins are being rewarded like you wouldn’t believe and the tournament is effectively half a round shorter than it would normally be, making problem one even worse. I won’t bother anyone with the math on this because it’s so trivial. Another obvious statement is that if you offered me a no-money bye in any round when I wasn’t a lock for the top eight, I would instantly accept. The whole thing feels wrong, unfair and distasteful.

Bad News 3: Not Getting to Play

The flip side of getting a smaller tournament is that people don’t get to play that many rounds when they’re not doing well. Often these extra matches are great fun for those who have been knocked out. A lot of people left Day 2 wondering why they bothered getting up. Note that a lot of these issues could be addressed by keeping one three-loss player around to play against the would-be bye and giving players four more rounds and another loss or two to give on Day 2, but that destroys much of the beauty of the structure and gives away two of its biggest benefits.

Bad News 4: Pro Tour: Chicken

While there’s more KFC action when we hit Japan, this could be described as the tournament where players played chicken for big bucks and far too often both players went off a cliff. This structure will make cheaters of us all, if not explicitly or technically, because it essentially forces the players to reach a negotiated settlement if a match is about to end in a draw. To allow that to happen costs both players money. Not only that, it takes a good chunk of that money and takes it out of the prize pool! That’s no way to play.

The problem is that the player who scoops always gets the short end of the stick. In this case, it’s easy to see that anyone failing to give back half the money that was won in that round deserves whatever revenge the other player rains down upon his ungrateful, meaningless existence. It’s harder to see that you’re entitled to half of everything that player gets once he has two losses on him, since he’d otherwise be eliminated. Even if you get that, it doesn’t compensate for Pro Tour points. Not only does one player have to trust the other without a contract in place due to the rules, he will get less than half of the pie even if he is treated fairly. This problem happens anyway, but this is the issue made explicit.

Bad News 5: Too Progressive

The system doesn’t grant enough money to the top finishers to reward them for their hard work, especially when they have a better than usual chance of being knocked out before they get there. A slower rise in the money curve earlier followed by a higher one later would solve that problem but introduce a new one: Players who won early rounds and lost later rounds going deep in the tournament and coming home with very little.

What is the advantage of this format over a Swiss system? In the end, other than ease of running the event there is little to recommend it. If you wish to give players a little something for showing up, I have no problem including some payout for points earned as a progressive distribution of some of the funds. Let’s not reuse this system, or at the very least we have some major holes to plug first.

The Format and Decks

I didn’t expect to have this much to discuss when I decided to do a roundup right after the tournament, so I don’t have the space (or time, when I think about it) to do a full analysis of the Tour. I was worried about that until I saw the announcement of the new database, which means that the substantial analysis should wait for later anyway. However, I can paint the broad strokes now. As usual, I had almost all of the pieces at one point or another but given how many bases I covered, that doesn’t exactly give me a perfect score. I knew about the possibility of cards like Sway of the Stars and Heartbeat of Spring and noted them as potentially interesting, but never got anything I liked. The same holds for Hana Kami, although there I was looking at almost exactly what was played: I had the engine, I had the numbers analyzed as the only way the deck could work. I just didn’t think it would work because I couldn’t cover all the bases with sixty cards. Cranial Extraction was too big a vulnerability and there was no good way to cover it and cover Night of Soul’s Betrayal and cover Samurai of the Pale Curtain and Hokori. If you exposed your engine at all, you were asking for trouble, as you had no choice but to hide behind it so often. The basic sideboard plan of boarding in threats and Graverobber to compensate seemed clear enough.

Why did it work?

The short answer as far as I can tell is that people didn’t stop it. As I said in my column, The Flower in the Room, the deck wouldn’t work if people decided they wanted badly enough to stop it. I figured they would do so, and that was a mistake. While the decks were obviously vulnerable to Cranial Extraction, they can survive it and that was the extent of most people’s response to the threat. I did just hear Randy say that I “nailed this format” but I am more humble than that because I feel like the last step is too important. I have high standards. The big difference between the decks at the Tour and the general public was that the Pros understood the importance of Final Judgment and the Myojin. There is enough time to reach that stage in the game, and once that happens Final Judgment will get you out of trouble. Yosei was also vastly underestimated and thought to be inferior to Kokusho. The first hint I got that the public was as wrong as it was came from one of my tests against a top Pro. Combining all that with access to Empty-Shrine, they now had good answers to the Snake and WW decks.

With those decks in check, the control decks can get more and more insane as they tackle each other. Once you reach the threshold where the decks are swinging at each other with legends and Final Judgment – which is then good against strategies of all kinds – the very top end cards move in to take over. I also flat out underestimated the Top, which is far better than I gave it credit for. Often misevaluating one card is one of the major mistakes in my testing. For example, our underestimation of Wildfire was huge in Urza’s block. Everyone who realized how good the Gifts decks could be didn’t figure out a way to fight them. They just played Gifts.

In other words, a strong argument can be made that the Red deck should have won this Pro Tour. No one played it, and I don’t mean no one who matters. I mean no one, at least not in the form that I’d heard about. If I had decided to make it one of the decks I focused on and written the deck up, things might have gone differently. If they replayed the Tour, I’d expect it to be a major factor, but no one played it. The deck simply looked too weak, and had too much of a White issue. It’s also possible that it did not have what it takes, no matter how good a position it might be in. Kai’s deck was another attempt to beat the control decks, and if it works the way I suspect that it does he was in fine position to win it all, but took three losses and was knocked out due to the lack of rounds. Historically such decks almost never win block Tours, with Tokyo being the only possible exception.

The other problem is that Gifts can choose to beat any one threat that it faces, so it’s hard to play a foil against it. Play Red and you risk Vital Surge or Candle’s Glow even if your build is good. Play White and opponents who give up control wars for removal will have you. Play control and you lose if he’s willing to lose to Hokori in game one. It’s quite a frustrating situation. Combine that with the difficulty of playing Gifts, which both gives it better winning percentages and causes people to underestimate its true power, and you have the makings of a power deck. As it always does, everything makes sense in the end. I plan to bring a more complete analysis later on when the database is up and running.