If you’ve been reading a lot of articles on Magic, you’ve probably been hearing the phrase “Addition through subtraction” a lot lately. A big part of why you’re hearing it is simply the way that things turn in the cycle of Magic.

I’ve spoken a lot in the past about Magic decks existing as a part of a kind of complex ecology. If we imagine it in this way, we have a world in which when all of something (say Faeries, as a deck) is taken away, this makes room for new animals to be the kings and queens of the jungle. The simple fact of the matter is this: in any given tournament, there are a finite number of wins. If you play for fun, you are only limited by your enjoyment of the game as you set out to find and acquire wins. If you play in a tournament, you’re taking a more finite amount (7+(# of players/2)^(# of rounds), at most, typically).

When you’re dealing with limited resources like this, recognizing how the lay of the land changes, and what this means for deckbuilding, is deeply important. As people have been evaluating Zendikar, I’ve already seen some phrases tossed out there by some very smart people that I can’t help but feel don’t understand just how deeply the landscape has changed.

Ladies and Gentleman, I predict that there will be a return of the Fattie. Unless Zendikar’s continued spoiling, in these last few moments before it is out, holds some big surprises, I predict we will once again see Fatties as a more regular visitor in decks, and not merely viewed as “a big body that will not get through.”

The big reason for this is simple: Bitterblossom (and to a lesser extant, Spectral Procession) is now gone.

Playing a Fattie in the time of Bitterblossom seemed an almost fruitless affair. What card actually saw much play that might “count” as a Fattie? Chameleon Colossus is about the only thing that comes to mind, if we want to be really harsh about it. Oh, occasionally a Doran would poke its head out, but it was pretty rare. It was just a nature of how cards get costed. Who could afford to spend the mana on something big and fat if Faeries (or Kithkin) could primarily just ignore it? Colossus managed to be a notable exception (with Elf decks like the one I gave to Sam Black for last year’s Nats being one of the sole decks to pack it), largely because it could partly ignore Faeries because of Protection from Black. Flying, a typically fantastic power for Fatties, rarely made the cut since the omnipresent token could usually be around to simply block. Trample and protection were the key abilities for a big creature in this time, which is partly why so many creatures were hamstrung for so long.

Fattie History

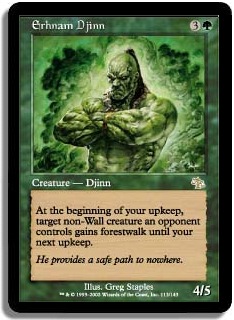

When we look at the long and storied history of the Fattie we really have to begin with on creature: Erhnam Djinn.

Sure, other biggish cheap creatures had existed before the Erhnam. Serra Angel and Sengir Vampire were both deeply popular Fatties before Erhnam was printed, but in this era, tournament Magic was hardly even born yet. Remember, the very first Pro Tour, with its deeply rough format, included Ice Age in the mix, and was probably the first event where people, at large, did much in the way of playtesting.

I still remember in that era that I was playing decks that could hardly be called constructed (“Let’s play all of the counterspells I own!”), and I began playing with a group of people that included some truly skilled players. A young Matt Severa was probably the most cutthroat of the tournament players I knew at the time (though it was Jim Hustad that really put me on the path of building “real” Constructed decks), and he was playing what was commonly considered the “best deck” of the era: Erhnam-Geddon.

Erhnam was such a powerhouse because he was simply so large for so little mana. Many of the die-hard Green players even complained that Erhnam was not really a Green card because he simply got plopped into pretty much any deck as a splash. Juzam Djinn was bigger, but its drawback was less than the problem of “take one damage every turn” and more the problem of “play not just one, but two black mana to get him out”. Erhnam got splashed everywhere. Yes, Erhnam could get taken out by a Swords to Plowshares, but after that you’d have to typically lose two creatures to deal with it. If you had an army of Savannah Lions and Pump Knights, you could suddenly be held back by one of this guy, and often far faster than you might have liked.

My own first fattie would probably be Uktabi Wildcats in my old-school Mono-Green deck, Green Machine. This was the kin of deck that seemed to consistently give me 9th through 12th place PTQ finishes, but no dice. I’d monkeyed around with Gargantuan Gorilla before that, but it hadn’t really gotten me very far (my deck beat everything with a Necro, it seemed, and lost to everything with a Balance in it, which was about 40-50% of the meta at that point).

But the person who really got things going with Fatties has got to be Jamie Wakefield.

Jamie’s influence is legendary. In many ways, he was the most influential writer in the business, with his incredible storytelling skill. Often considered the godfather of Midrange, as I’ve written before, The Wakefield School of Magic could often be summed up thusly:

“The last Fattie that they don’t deal with kills them.”

Jamie ended up 18th at Pro Tour 1 with his “solid Black, big creature discard deck”. As we’ve slowly grown accustomed to bigger and bigger creatures, the size of his big creatures might be underwhelming now, but in an era where creatures, by-and-large, were pretty small (Orcish Canoneers saw play around then because it actually killed creatures!), his big creatures were downright monstrous:

Even then, Jamie was a fan of utility creatures like the Night Stalker, but there was a reason for his love of these things.

The Value of Fatties

What makes a Fatty any good? Why not just play something cheaper? And what is a Fattie?

If we think of the mana curve, starting from zero mana and going up to eight mana, we will find that we have contained virtually all of the creatures in Magic that regularly get cast in tournament games. With few exceptions, though, the cheap creatures (0 to 3) are typically quite, quite small. The truly expensive creatures (8+) are just too expensive to be able to expect to get out on the table with any reasonable consistency.

This leaves us the middle-to-expensive slot (4-7). Of this, we’re still really pushing it if we’re going to be planning of 6-drops, let alone 7-drops. That’s a ton of mana without cheating somehow (Dark Ritual, Natural Order, Resurrection, Seething Song, Show and Tell, etc.), and while these are cards that can sometimes be considered, they often really have to be set aside when you’re trying to think about what is a realistic cost. Six mana, after all, is often the mark where people ask, “Did that card win you the game?” (e.g., Broodmate Dragon). Something super expensive might be big, but it doesn’t really count as a Fattie for the purposes of this discussion.

Four and five is really where the sweet spot tends to sit. These cards are just cheap enough to get down on the table with any reasonable consistency and have an impact in time before a game might be all but decided. Back in the day, the litmus test for a Fattie tended to be 4/4 or better, so that it could survive a Lightning Bolt. Once again we live in the days where 4/4 is probably the minimal size, as we see a return to Bolt’s play.

What the Fattie does is two-fold:

1 — It serves as an engine for Virtual Card Advantage

2 — It typically transforms Virtual Card Advantage into actual Card Advantage

While a Fattie can and does get killed or removed (Swords to Plowshares being the classic way, but with Terminate, Path to Exile, and other cards being more contemporary means), it changes the table immediately when it hits play. An opponent playing several smaller creatures has to ask themselves, “Is it worth attacking?”

In some cases, the answer is just going to be no. They sit back on their heels with their creatures and wait for something to change. Maybe they’ll get enough creatures to decide the attack is worth it. Maybe they’ll draw a straight up one-for-one removal (like Maelstrom Pulse or Swords to Plowshares). Or maybe they’ll find something to help get the Fattie out of the way.

For the entire time that they are sitting back, you have effective Virtual Card Advantage. Those creatures might as well not exist for all the good they’re doing. At some point, though, it’s likely that these creatures are going to come in. Maybe it will be because a pair of removal spells is being employed to take the creature out (Bolt, Bolt). Maybe it will be that a creature will get some help after it is blocked, taking the Fattie out. Maybe it will just be decided that losing a creature to get the damage in is worth it. Whatever the case may be, if a single spell isn’t taking out the creature, your Fattie is supplying you card advantage.

When you put a Fattie in a deck that has other ways of dealing with creatures, the Fatties’ inherent ability to acquire card advantage from smaller-creature based decks can be a huge boon. The player who rushes in with their creatures only to meet with an unexpected pair of Doom Blades, for example, might find their entire force decimated, and even after they finish off the Fattie, they are down a card and often out the majority of the brunt of their attack.

The Fattie is less powerful against a more controlling deck, but it still requires an answer. Here, again, if it is sufficiently large, there might not be many answers for the creature short of dedicated creature kill. Trying to Bolt a Lord of Extinction to death, for example, is typically futile. Something smaller might be able to be killed in this way, but again, often at the cost of an extra card. And as Jamie said, if you don’t deal with one, well, you’re dead.

If Fatties are so good, why haven’t we really seen much of them in Standard in forever?

The big reason is environmental.

We just got out of a world of Bitterblossom and Spectral Procession. The abundance of tokens was a real problem for most Fatties; they simply couldn’t get through with any degree of regularity. What’s worse, they were easily replaced. When you add persist on top of tokens, the last two years of Magic have not been kind to the Fattie.

So, before that?

Tarmogoyf. What a monster! What was the point of trying to spend mana on a Fattie when everyone and their brother got to play with Tarmogoyf for fat? It’s bad enough for the more traditional Fattie that Tarmogoyf could be big for so cheap, but adding insult to injury, it was often simply bigger than any Fattie could typically expect to be. When you take into account how quick Tarmogoyf games could be, it wasn’t a particularly exciting environment for the Fattie.

And before this? Umezawa’s Jitte. Any creature could be big and huge with Jitte in the mix! Dropping the mana for a bigger creature was almost crazy when a Jitte could so swiftly make the choice a waste of time.

And before that, we had to worry about Affinity. Here, things were so fast that traditional Fatties didn’t tend to show up, and when they did they could be easily overwhelmed by an Arcbound Ravager. A similar problem crept up before that with Psychatog.

As we go back, further, we hit Flametongue Kavu. FTK all but defined Standard. If your more expensive creature couldn’t survive FTK, it wasn’t worth playing. At this point in the game, Wizards wasn’t in the habit of pushing the power levels of creatures, and so this meant that you’d have to start going to the six-drop, taking things out of range of the more reliable Fatties.

And before that we had Rebels (though some Fatties did try to persist in this era), and before that we had the card Time Spiral. And before that, Survival of the Fittest and Oath of Druids.

If we look at the history of Standard, things have been pretty hostile to the Fattie ever since, essentially Stronghold. Stronghold.

If you’re not sure when that was, that was February, 1998.

While there have certainly been great Fatties that have seen play in the interim (Ravenous Baloth, Arc-Slogger, and Loxodon Hierarch quickly come to mind), the environment simply hasn’t been that amenable to them. The big creatures that have been out there have been “build your own” like Affinity creatures, or cheaters (like reanimation or Madness to get it out). Playing a Fattie, fairly, has been incredibly rare.

No wonder, then, that people have hated on Fatties (and Midrange styles, in general) in recent time. Fatties simply haven’t been an exemplary choice. They’ve been out of style for a good reason for a long time.

The New Era

Quite simply, we’re entering into a new era. While there are certainly good token-creating cards out there (like Elspeth), it looks like it is shaping up to be a format where Fatties are going to matter again.

The ways to make tokens are few, and even where they can be made, they simply aren’t as potent as the old ways. Elspeth and Conqueror’s Pledge are not Bitterblossom or Spectral Procession. Captain of the Watch might put out three tokens, but it costs a hell of a lot, and so it is going to get to the party pretty late.

The ways to cheat a big creature into play are also few and far between. Polymorph is one of the best, and it is quite awkward. Building up your own creatures is an option, certainly, but importing Esper Stormblade is about the only way to get something close to appropriate on that measure.

As for “cheap” large creatures that already exist, the baseline is easy: Woolly Thoctor. Here, you have a card that is going to be hard enough to cast that it really does self-limit in some ways, ecologically speaking. This is not going to be a world like the one defined by Tarmogoyf, where everyone might just try to fit it in. Instead, it is a world where a deck might be able to fit Thoctor into it, but everyone won’t be warping their deck hoping to find room for Thoctor.

In fact, it actually looks like the entire format is largely going to be defined by a single Fattie that we’re already quite familiar with:

Unless something changes between now and the full spoiler, she is the litmus test for the format.

Environmentally speaking, this will in-and-of-itself, but a damper on the Fattie. People are going to be more prone to packing bona fida creature kill spells just so that they don’t fall prey to her. As a result, the incidental hate will fall onto other Fatties too. But, like in the old days, this doesn’t mean that people won’t simply run out or not have it. Effects like Gatekeeper of Malakir and Doom Blade will be around, but this doesn’t mean a Fattie shouldn’t be run, it merely means that you should have enough cards that are significant that you don’t get blown out by a single such card.

If you’re going to compete with Baneslayer, what this means is that you’re going to have to be good enough to even warrant notice.

What creatures are good enough Fatties, then?

Honestly, there aren’t many. Some, like Battlegrace Angel, simply feel completely outclassed by the ubiquitous Baneslayer. While Battlegrace could be played in addition to Baneslayer, what we’re really looking for, here, are cards that could potentially be played in a Baneslayer-defined world without feeling below-the-bar.

I’ve been pleased by this card since I first saw it. Large for a very cheap price, with an ability that is actually relevant, this card isn’t as hard-hitting as some others are, but it is fantastic defensively.

Where Baneslayer has sheer power, Djinn has this strange ability that strikes me as being potentially ridiculous. I have visions of sugar plums, maybe, but it doesn’t seem crazy to get a Djinn to do some ridiculous things, and I’m sure someone out there will manage to cast Cruel Ultimatum off of it.

I still run 4 of this in my current Shards Block deck. An Adjudicator can totally turn around nearly any game that it manages to live through, and causes so many scoops that it’s shocking.

Perhaps not powerful enough without help from a Warchief, the Razerunners are still fast and large, and have the ability to “evade” with their special power.

5/5 for 5 is a great start. While Ant Queen doesn’t race Baneslayer particularly well (15-20, 10-20, 5-17, etc.), its ability is worth recognizing as incredibly powerful. Not everyone is going to be playing White, and this card is definitely a contender.

Potentially larger to begin (though at a cost), Mycoloth can definitely race a Baneslayer or simply set up an amazing army that will quickly get out of control if not answered. If it is answered immediately, Mycoloth’s cost will seem painful indeed, but it is still deeply scary.

Completely able to tussle with a Baneslayer, this card is also resilient against a lot of the cards that people might pack in order to deal with Baneslayer. Expect this one to see a fair amount of play.

Deeply difficult to cast, it has the added benefit of being able to be a Nevinyrral’s Disk with the right card in hand. Trample helps immensely, too!

I’ve gushed about him before, but expect him to really start shining now. Easily able to race basically anything, this card is going to demand that you deal with it. This card could easily be cropping up as decks figure out that they can play it.

At four mana, cheap for a 5/5, but with an ability that might simply be really less than good right now. Still, placing itself deeply in Green/Red, it might be the least suited to handling a Baneslayer without risky cards like Giant Growth and friends. Definitely a powerhouse, though, if only because it is so large so quickly.

Even with Tizoc’s Runes of the Deus to power it up, Uril is a monster. Putting a Gigantiform on it seems like it could be good, or maybe some other enchantment will make the cut, given how Uril cuts out most of the risk.

From Zendikar (SPOILERS BELOW):

World Queller

3WW

Creature – Avatar

At the beginning of your upkeep, you may choose a card type. If you do, each player sacrifices a permanent of that type.

4/4

This card seems like it could easily be strong enough in a completely different way than Baneslayer to be played either in addition to Baneslayer (most likely) or in its stead (less likely).

Malakir Bloodwitch

3BB

Creature – Vampire Shaman

Flying, protection from white

When Malakir Bloodwitch enters the battlefield, each opponent loses life equal to the number of Vampires you control. You gain life equal to the life lost this way.

4/4

Baneslayer Angel doesn’t have protection from vampires, and so the Bloodwitch is certainly going to be reasonable. Essentially a Sengir Vampire upgrade, if you ask me, the Bloodwitch could end up being a staple in Vampire decks.

Obsidian Fireheart

1RRRR

Creature – Elemental

1RR: Put a blaze counter on target land without a blaze counter on it. Lands with blaze counters on them have “At the beginning of your upkeep, this land deals 1 damage to you”. (The land continues to burn even after Obsidian Fireheart leaves the battlefield.)

4/4

Like Goblin Razerunners, but bigger to begin with, and less costly to activate in many ways, the Fireheart can really tear people a new one. Expect this to be a fixture.

Conclusion

People haven’t seen a format so rife for Fatties in forever. When you’re looking at the world anew, it is important to remember that things really are new. Just because it used to be doesn’t mean it is.

I know that I have spent a lot of time wishing that the world Magic was still the world that Jamie Wakefield vision of the game initially saw it to be. That the time that the game is doing the best for the average player out there, the player who likes to play against things that they view as fair. I know that a lot of people are really going to miss the times that a Fattie wasn’t a good thing, but believe me, it’s good for all of us. Most of the things that make people quit the game are the same things that make the game bad for Fatties.

As I try to figure out what works in Standard, you can expect that a fair amount of the cards I try are going to be ones that might make Wakefield smile.

Until next week…