Today, for perhaps the first time in my life, I feel like a comedian standing on a stage, looking out at a crowd who’s interested in hearing the usual… some pithy comments about my dog and his bathroom habits, perhaps a story about a Porta Potty, maybe some funny nicknames that I used to have, and a few jokes about politics. And as I look into all of these smiling faces, plied by the funnier comedian that I paid to perform before me, I start talking about Magic Theory.

I’m talking about some hard-core, “the club owner is really, really pissed off”

Magic Theory.

You know what I think?

The concept of card advantage is dead.

But who is responsible? Who killed it?

Is it possible that

we

killed it?

Well, maybe it wasn’t “us” per-se, but what about great theorists, those who pioneered concepts like

The Philosophy of Fire

and the

importance of tempo?

Did they put nail after nail in the coffin?

Like Larry and Richard from

Weekend at Bernie’s

we’ve been struggling to keep the illusion alive, to discuss things in terms of card advantage and disadvantage, all the while admitting to ourselves and others that it is only a piece of the puzzle.

We are people who understand how gravity works on earth – it’s simple, things fall! – but who struggle to articulate how Neil Armstrong could have jumped so high on the moon.

We are human beings who search for meaning in everything that we do. We struggle to categorize, to define, and to explore. As intelligent Magic players, we crave

precision

and a way to understand the “

whys”

and “

hows”

of our craft.

In this spirit I humbly submit that the concept of card advantage represents a pair of beautiful shackles – it is attractive and comfortable, and yet it binds us.

Before we can seek to break free, though, we need to understand our restraints. Let’s take a look at how we traditionally have understood Magic – from there, let’s take a hard, close look at what we know now.

Is it possible that we can create a better theory?

Traditional Card Advantage

“You have to know the past to understand the present.” – Carl Sagan

As Magic players – and especially as tournament-level players – we understand the concept of card advantage almost intuitively. Whenever we take an action that

creates a favorable disparity between the number of cards that we have and the number of cards that our opponent has,

we have created card advantage.

In an

excellent introduction to this concept,

Ted Knutson enumerates three major ways in which we can do this:

1) We can draw more cards than our opponent.

2) We can force our opponent to discard cards.

3) We can force our opponent to spend more cards than we do. *

In opening his discussion of card advantage, he proposes an example where two copies of the same deck (Deck A and Deck A’) are pitted against one another, except that Deck A gets to draw two cards each turn, while Deck A’ plays by the traditional rules of Magic. In this example, we will expect Deck A to win most of the time. This makes perfect sense. In fact, we can’t (and

shouldn’t

) objectively argue that creating card advantage is a

bad

thing – as numerous theorists have proposed, it’s often quite helpful – but we should understand that the simple act of drawing extra cards doesn’t win a game of Magic and

occurs within a context

(bear with me here; I know this seems

overly simplistic). Patrick Chapin

said this very well

when he wrote that “card advantage is a good thing, but that is only because in general a card in your hand is worth more than a card in your library. This equation changes, and there ‘s always some sort of cost associated with obtaining card advantage.”

For example, a traditional understanding of card advantage often isn’t useful when assessing decks that attempt to win through “tempo” or an application of “the philosophy of fire.” As a more specific offshoot of this thought, we frequently say that red decks usually don’t care about card advantage; they only care about dealing twenty damage (or, more appropriately, lethal damage).

Zvi Mowshowitz once wrote that “extra cards don’t matter in [tempo-based] games unless one player runs out of cards and therefore things to do with his mana, or he needs to go digging for the tools he needs.”** This almost always is the case, but it leaves us in an awkward position – traditional card advantage can’t really explain a matchup like “Burn versus Burn,” but, at the same time, we must acknowledge that a burn deck that draws all of its Lightning Bolts and two Fireblasts will beat the same burn deck that draws all of its Shocks and two copies of Hammer of Bogardan.

To address this gap, we look to supplemental concepts, like the “philosophy of fire,” to demonstrate the ‘advantage’ of a Lightning Bolt over a Shock – once argued to be the baseline ‘metric’ in Magic at a value of two damage, one card, and one mana – because one (the Lightning Bolt) accomplishes a goal (dealing twenty points of damage) better than the other.

We might ask, though, whether this and similar holes in the application of traditional card advantage theory to Magic constitute a problem with our thinking or are mere artifacts of our “necessarily” multi-faceted analysis.

Virtual Card Advantage

“Words have no power to impress the mind without the exquisite horror of their reality.” – Edgar Allen Poe

We might find it ironic that one of the first “nails in the coffin” for traditional conceptions of card advantage bears a similar name.

Eric “Dinosaur” Taylor (edt) popularized the theory of virtual card advantage, which is a situation where no one actually loses cards, but certain cards in play are nullified. The archetypal example of this usually involves the card Moat.

If we’re staring down three copies of Ulamog’s Crusher with no cards in hand and only five lands in play, our copy of Moat invalidates all three Ulamog’s Crushers, in addition to other creatures without flying, until it’s removed from the board.

This conceptualization makes perfect sense… but why do we call it card advantage? Our working definition for card advantage is

a favorable disparity between the number of cards that we have and the number of cards that our opponent has

.

When we play a Moat against three Ulamog’s Crushers, we haven’t changed anything except the context in which our cards exist. We might

consider, then, the idea that

“virtual card advantage” takes a valid, reasonable concept and inappropriately attempts to characterize it.

To explain this in other terms, imagine that we’re alien settlers on an unpopulated Earth, and our first experience with earthly food is to find a tree producing a round, orange fruit that we appropriately call an “Orange.” The fruit from this tree is delicious and sustains us, but after some exploration in the countryside we discover a new type of tree that makes a differently shaped red fruit (apples). Because we’ve sustained ourselves with a single fruit, an “orange,” we call the new fruit a “Red Orange.” We then discover a plant growing from the ground that produces a round, red food that might be a fruit, but we’re not sure (tomatoes). We call this ‘fruit’ a “Round Red Orange.” And so on.

Because we inappropriately have selected a specific fruit (an orange) as the basic unit with which we attempt to understand all other fruits and vegetables, we potentially have created confusion that could have been avoided by using a broader concept as our basic means of classification and analysis.

Now that we have a mutual understanding of the basic principles of card advantage, we can begin to seek a way to break free.

Card Utility – A Revised Metric

“The Candle is a great boon to mankind, as approved by all men. Therefore it cannot be destroyed by the whim of one.” – Harmony 9-2642 (“Anthem” by Ayn Rand)

“Card utility” is not a concept that is designed to supplant card advantage in the annals of Magic theory. Rather, it is an attempt to begin to contextualize multiple levels of Magic into a coherent whole. It is a way to theorize about what we already are doing.

We should begin, though, at the beginning, as Lewis Carroll’s king once suggested.

In Magic, we deal with four fundamental, external components: Resources (R), Cards (C), Context (X), and Purpose (P). A discussion of card utility

relies on our understanding of these features.

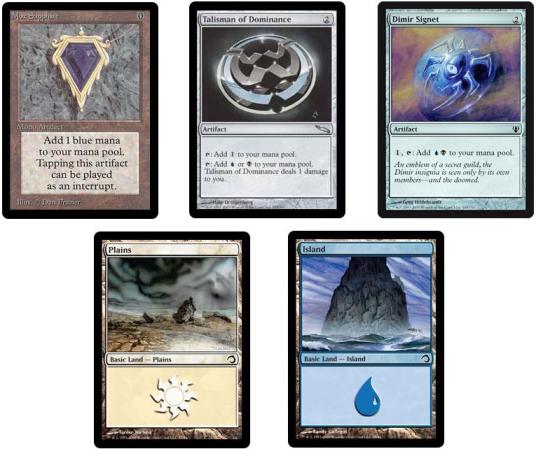

Resources

represent the ability and potential (i.e. Mana) to play non-Resource cards (or Resource cards with a casting cost). Resources primarily are derived from land but also can be found in a variety other sources, such as Moxen, “Talismans,” “Signets,” etc. Resources typically are a limiting factor in Magic, because in a given turn, we cannot play cards with casting costs that do not correspond to our available resources. As we will discuss shortly, cards that increase our available resources (such as a Mox Sapphire) often, but not always, have a high level of utility if played early in the game, and a low level of utility if played later in the game.

Cards

either take the form of Resources (things that produce mana) or of spells, which we use to accomplish specific Purposes. Each card that we have in our hand has a certain amount of utility that varies frequently based on:

a) Our available Resources.

b) Our current Purpose(s).

c) Our current Context (similar to what often is called the “game state”).

Any time there is a shift in our available Resources, our Purpose, or our Context, we should reevaluate the utility of each card in our hand.

Context

is a broad vision of the “game state.” Every time our Context changes we need to reevaluate the utility of each card in our hand. Every attack, every block, and every decision similarly affects our Context. In addition, information that we gain from sources outside of the physical game (obviously within the boundaries of fair play and DCI regulations, i.e. our knowledge of the likely components of a deck) constitutes our Context. For example:

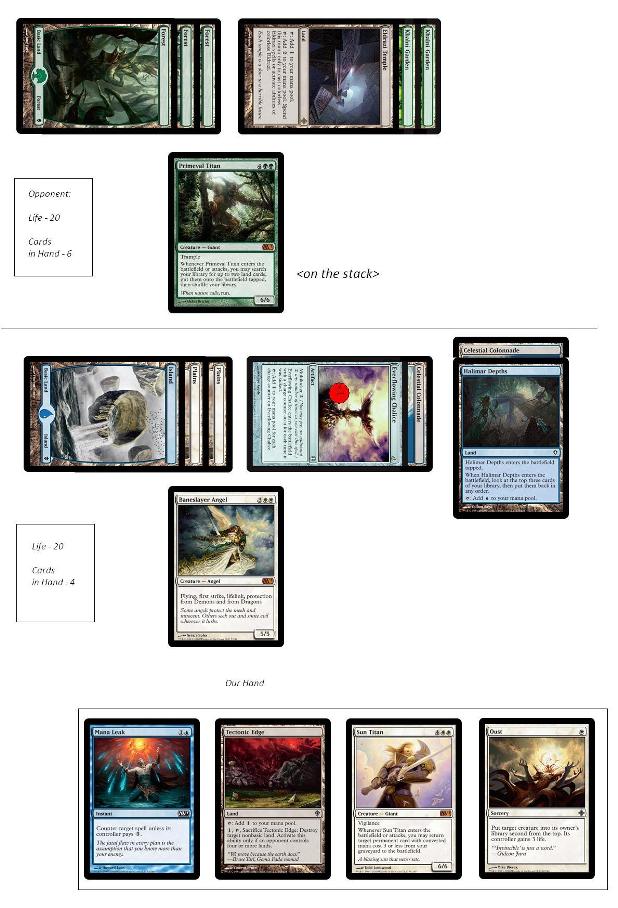

This game state represents a very slow game between Eldrazi Green and U/W Control. The U/W Control player made a mistake by playing a Plains on his sixth turn instead of a Tectonic Edge. When we look at our Context in this game state, we examine:

1) The obvious:

a. There is a Primeval Titan on the stack. If it resolves, our opponent probably will tutor for an Eye of Ugin and an Eldrazi Temple.

b. We have one card in hand that can deal with it immediately (Mana Leak).

c. We have a Baneslayer Angel in play, which can kill our opponent in four turns if it is not answered.

d. We have Celestial Colonnades in play that could speed up our clock by a turn.

e. We can Oust the Primeval Titan next turn if we don’t mind our opponent tutoring for lands. This also might affect how quickly we can kill our opponent.

2) The

slightly

less obvious:

a. Our opponent has not played a spell prior to Primeval Titan. Unless he drew a copy of a card like Explore or Cultivate on his sixth turn (his current turn), he is unlikely to have one in hand.

b. Eldrazi Green runs the card Summoning Trap, and the likelihood that our opponent has one copy in his hand is mathematically fair to good (he likely is running four copies and has drawn 21.7% of his deck). In addition, we might suppose that there’s an additional inductive possibility that he has Summoning Trap because his hand probably is composed of a mixture of Resources (lands, in this case) and spells that cost six mana or more (Primeval Titan, Wurmcoil Engines, Summoning Traps, and Eldrazi creatures). This affects the utility of our Mana Leak.

c. If our opponent tutors for Eye of Ugin and Eldrazi Temple, we will need to use our Tectonic Edge next turn to prevent him from tutoring for a colorless creature card or from casting a Kozilek or Ulamog. If he has another Eldrazi Temple in hand or draws one, he will be able to cast either of those cards anyway, if he has one or both in hand.

d. Are there any special cards in our decklist that are designed to beat Eldrazi Green? We haven’t seen a Preordain or a Jace (of either variety) yet, so we have a reasonable chance to access to a card like Volition Reins, if we’re running a copy or three. If we don’t draw the card directly, though, (i.e. if we draw a Jace, the Mind Sculptor) we will be restricted in terms of what we can do on the following turn by our Resources.

3) The “other stuff”:

a. Has our opponent made any comments about being “land flooded?” Does he seem frustrated or confident? Is he smiling or frowning?

b. Does our opponent seem to be an inexperienced player who simply kept an awkward hand, or is he a more experienced player who likely has a reasonable plan against U/W Control?

c. Are you upset about having played the wrong land last turn? If so, are you focusing on that mistake instead of working to overcome it?

All of these factors

and more

constitute the things that we deliberately and subconsciously are considering (or that we should be considering) when we evaluate the Context in which we play our cards.

And finally…

Purpose

is the goal that we want to accomplish. At any given time, we can be working toward multiple Purposes, but they must be prioritized. We never should make decisions when playing Magic without considering our Purpose(s). These include both long- and short-term goals. Examples include:

a) Deal twenty damage as quickly as possible (i.e. Kuldotha Red).

b) Don’t lose the game (all decks, but control decks typically begin with this as their highest purpose and shift it lower as they stabilize).

c) Win by executing an alternate win condition (i.e. a “Mill” archetype).

When Mike Flores famously asked

Who’s the Beatdown?

he was suggesting that players should determine and correctly order their Purposes.

As we discussed earlier, card utility is a function of Resources, Cards, Context, and Purpose(s). Specifically, a given Card’s utility is determined by the Context in which it currently exists and the extent to which it contributes to our current Purpose(s), and is limited by our available Resources.

Allowing for variance (i.e. random chance), a player who maximizes his or her card utility is more likely to win than a player who fails to doso.

Card Utility – Example One

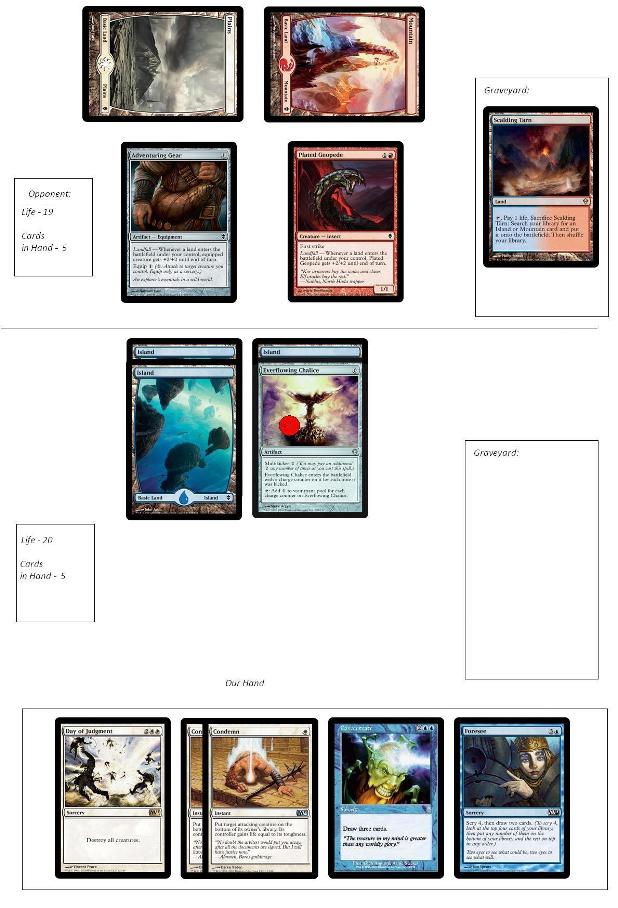

For this example, which is fairly simple but is illustrative of card utility, let’s assume we are playing a strange Constructed format similar to Standard but with the addition of Concentrate (which we have added to the format for this one game to illustrate a point).

We’re on the play this game, and it’s our third turn. We’re playing U/W Control with Concentrate, and our opponent is playing some version of Boros Equipment. Our opponent opened with Adventuring Gear into a Plated Geopede. Next turn, he will have a grip of six cards, and if one of those cards is a Scalding Tarn, Arid Mesa, or other fetchland he will be attacking us for

at least

nine damage, and there isn’t anything that we can do about it.

We are ‘color-screwed’ and have played three Islands and an Everflowing Chalice set at one counter.

If we unquestioningly accept the premise that ‘card advantage is good’ then we will play Concentrate and draw three cards. Intuitively, though,

we know that playing Concentrate isn’t the correct thing to do.

Why?

In terms of pure card advantage, Concentrate is better than Foresee (it is a three-for-one instead of a two-for-one). If we consider card utility, though, we are able to explain why our intuitive play (Foresee) makes sense.

As the game currently stands, we are limited by our Resources. Since we don’t have access to white mana, the current utility of three cards in our hand (Day of Judgment and two Condemn) is incredibly low. If we were able to play those cards, their utility would be very high because our opponent has one serious creature-based threat on the board, with more likely on the way.

Because we know that ‘card advantage is good,’ we see that drawing three cards has a high level of utility. However, Foresee allows us to access two of up to six different cards, and although drawing two cards isn’t ‘strictly’ as good as drawing three cards, we want to maximize our chances of drawing a Plains because doing so drastically will increase our hand’s overall utility. This is how we know to play the Foresee this turn.

The Context is important, though. If we examined the exact same board position except our opponent had not yet played a creature (i.e. he had six cards in hand instead of five and only an Adventuring Gear on the board), we probably would be inclined to play the Concentrate, because having the Resources to play a card like Condemn when there are no creatures on the board does not drastically increase your hand’s utility.

Card Utility – Example Two

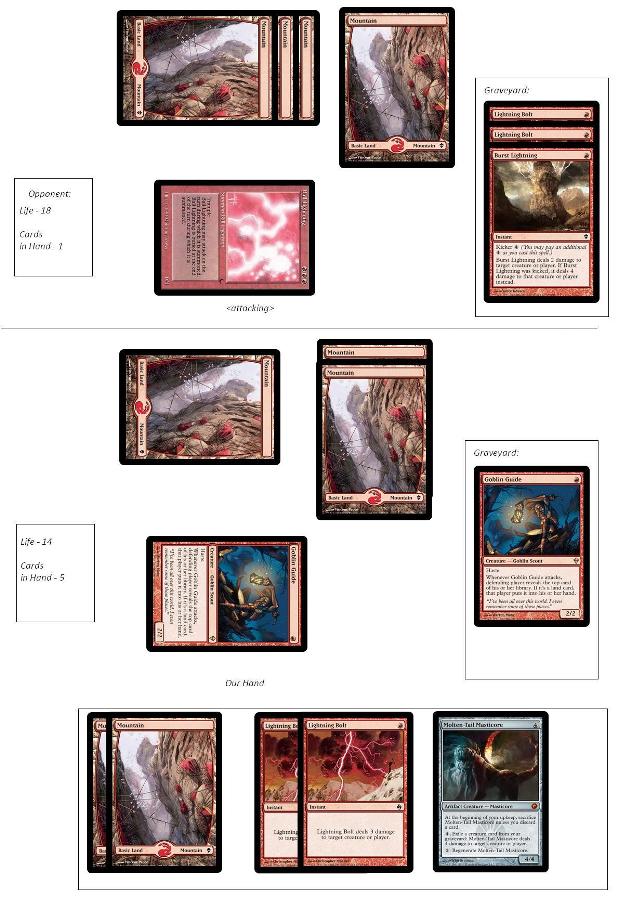

Now, let’s begin by focus on a slightly more complex example using two red decks:

It’s our opponent’s turn, and we’re being attacked by a Ball Lightning while at fourteen life. Our opponent has only one card in hand after hitting us with two Lightning Bolts and using a Burst Lightning to kill our turn 1 Goblin Guide (he didn’t get a land off of the trigger).

We now have to decide whether or not to use a Lightning Bolt to kill the Ball Lightning.

Players frequently will fall back on one of two ‘traditional’ Magic concepts when making such a decision.

First, a

basic

conception of card advantage suggests that killing the Ball Lightning is card disadvantage, because it is a creature that is going to die anyway, and we’re at fourteen life while our opponent has only one card in hand.

Second, a

basic

application of a tempo-based theory suggests that we’re a red deck, and, although we are on the draw, our Lightning Bolts should reduce our opponent’s life. Zvi once described tempo as “efficiency of time and mana.” While we technically gain some mana (as we’re spending one red mana to counter three of our opponent’s mana), we potentially set ourselves back in terms of ‘time’ (although a more advanced perspective might suggest that this is improper role assignment; it reasonably can be argued that we aren’t really attempting to win through tempo in this case).

Intuitively, though,

we’re drawn to the idea of using a Lightning Bolt on that Ball Lightning

.

Why?

Using a Lightning Bolt on the Ball Lightning generates the most utility.

Let’s examine the scenario in a slightly lengthier manner than we might use in an actual game of Magic. In fact, some of the things that we discuss here are things that we subconsciously process given a certain threshold of experience with the game.

First, we have considered Resources. We have two lands in our hand and three in play. We aren’t really limited by our Resources. On the other hand, our opponent has four lands in play. This is a key number that we consider when discussing…

Cards and Context – our opponent only has one card in hand, but he probably can play every card in his deck with the four lands that he has in play. Does he run Elemental Appeal? Does he run Koth of the Hammer? Does he run Molten-Tail Masticore? Are we concerned about any of those cards?

We will play our own Molten-Tail Masticore on the following turn, and his only way to kill it before we reach “regeneration mana” is to kick a Burst Lightning or to have a burn spell in hand (i.e. a third Lightning Bolt) and to draw a second burn spell

. If his last card is a Koth or a Masticore, we can kill it with our own Masticore activation. This suggests that the cards that he potentially might draw in the next few turns that can provide

him

with the

most

utility are those that directly will attack our life total, such as Burst Lightning, as opposed to cards that indirectly will do so (such as a Plated Geopede).

We currently have five cards in hand, but they have varying utility. Obviously, the Molten-Tail Masticore is currently the best card in our hand. Left unopposed, it will win the game very quickly. Our Lightning Bolts have utility as well – they can defend us against our opponent’s creatures and spells (i.e. Elemental Appeal), and they can reduce his life total. The first of two lands in our hand has tremendous utility because it enables us to cast Molten-Tail Masticore. The other land is “nice” but don’t really contribute a lot of utility outside of enabling the possibility of a kicked Burst Lightning later in the game or of casting a spell that costs four mana while regenerating our Molten-Tail Masticore, given a sixth land. We also have a Goblin Guide in play that slowly can reduce our opponent’s life total.

While it seems like we have a five-to-one “cards in hand” (CIH) advantage over our opponent, we more realistically have a four- or four-and-a-half-to-one CIH lead in the current context, based on our assessment of utility. That is still a meaningful advantage, though, in addition to the benefits provided by our active Goblin Guide.

Next, we consider our Purposes. We might suppose that our primary purpose right now is to deal twenty points of damage as quickly as possible. We are, after all, playing a red deck. However, lurking in the background is our supposed ‘secondary’ purpose: don’t lose the game.

We should consider how we might lose this game. At fourteen life, if we take the hit from the Ball Lightning, we drop to eight life. Although our opponent already has cast a Burst Lightning, if a combination of his one card in hand and his next two draws is land, Burst Lightning, Burst Lightning or land, Staggershock, Burst Lightning, we’ll lose the game within two turns. If we play carefully, this is one of the only ways that we might anticipate losing this game.

Should we invert our hierarchy of Purposes? It seems like we should consider it, at least for a turn.

Recall the idea that

a player who maximizes his or her card utility is more likely to win than a player who fails to do so.

We might ask how we can

minimize

our opponent’s utility in comparison to ours. Our opponent’s Purpose at this point is to “burn us out” from fourteen life. If we use Lightning Bolt on his Ball Lightning, then his remaining card has reduced utility.

In other words, our opponent’s cards have utility only insofar as they accomplish his Purposes. If we allow ourselves to drop to eight life, we also increase the utility of cards like Lightning Bolt and Staggershock. We enable many more scenarios wherein our opponent can draw a combination of cards that will win him the game. Furthermore, we have anticipated a statistically unlikely but possible scenario in which we might lose in the next two turns despite our superior board position.

Having gone through these varied thought processes, we decide to use a Lightning Bolt on the Ball Lightning.

Where would we go from there? We then untap and play the Molten-Tail Masticore.

We might also

consider

holding back our Goblin Guide this turn because its trigger slightly increases the odds that our opponent will be able to kick a Burst Lightning to kill our Molten-Tail Masticore before we can regenerate it.

Where Are We Now?

When we discuss something like Card Utility, our goal is not to suggest that we currently play the game incorrectly. Far from it – we intuitively understand the correct play in many difficult situations.

What we add by introducing the term Card Utility is a means of explaining and rationalizing difficult decisions within a uniform system.

Several other Magic players have attempted to develop a single system to explain Magic – most recently, Patrick Chapin

did so very astutely,

and his theory largely is sound, but it also is restricted in the sense that it uses our preexisting terminology, all of which comes with ‘intellectual baggage.’

If we try to explain everything we do in terms of tempo or card advantage, for example, we make the same mistake as did the aliens who landed on Earth and started labeling every fruit as a derivative of an orange. Some plays that we make in Magic simply extend beyond calculations with our traditional units of analysis, like card advantage, and more reasonably can be explained by examining utility.

Is it possible that developing a new way of discussing Magic theory, including new terminology, has significant practical application?

Magic players with different levels of play skill often have different levels of understanding of theory that mirror those levels of play skill. Consider the example of a freshly minted tournament player who recently has learned about card advantage. At the next Friday Night Magic draft, he doesn’t Disperse his opponent’s turn 4 Chrome Steed with his mono-blue deck because he wants to save his card for a time when it can provide card advantage (he probably loves the idea of Dispersing a blocker when his opponent triple-blocks his Steel Hellkite). Intuitively, he probably knows that he should Disperse the Chrome Steed because his hand is full of slightly more expensive, but powerful cards (perhaps a Contagion Engine and a Steel Hellkite). Because he has only been exposed to the theory of card advantage (and not to tempo, the philosophy of fire, or dare I suggest, card utility), his understanding is incomplete; the saying “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing” is especially true when that knowledge is a single component of a much larger theory –

and especially when he intuitively knows the correct play (we Magic players tend to be fairly intelligent) and ignores it in an attempt to improve.

Remember that we strive for meaning in everything that we do. Part of that aspiration is the ability clearly to communicate our choices with each other, even about something so ‘simple’ as a game of Magic. When we have the ability to communicate more clearly, we can learn more effectively and efficiently from the ‘Masters.’ We cannot emulate the truly great Magic players, though, if we don’t completely and fully understand what they are doing and how they are making decisions about the game.

As competitive Magic players, we focus on making the correct play – and when we understand Magic as part of a single coherent system with uniform terminology, we’re likely to make the correct play more often.

Is it fair to say, then, that all this theorizing might actually help us to win?

* This example presumes three ritual effects (i.e. Seething Song, Channel the Suns, and Cabal Ritual) to cast Mind’s Desire with three storm copies.

** Unfortunately, I can’t link you to Zvi’s article on the topic because it currently (and inexplicably, for nearly six-year-old content) requires a subscription to read.