Carsten Kotter recently wrote an excellent top-level breakdown of today’s Legacy metagame. He posited that there are three dominant approaches to the format: Delver of Secrets based tempo decks, Deathrite Shaman based midrange decks, and cantrip-based combo decks. I agree with his summary. I also agree with his point that there are a lot of ways for cantrip-based combo to beat the other two approaches.

The Omni-Tell list that I wrote about and recorded videos on in the past two weeks is a very well positioned combo deck right now for exactly that reason. The U/W/R Delver list that Gerard Fabiano took to the top of SCG Legacy Open: New Jersey is a fresh take on tempo.

Deathrite Shaman, however, has been slowly getting out-teched. Jund has the fatal flaw of not playing Brainstorm, so I don’t know how much work can be done there. Shardless BUG has a lot of conditionally powerful cards that force your hand in a lot of deckbuilding decisions. Esper Deathblade is a mishmash of powerful cards, but you have to cut some eventually and can easily cut the wrong ones. Here’s why I hate them all:

1) They’re reactive.

2) None of them have a good plan.

This deck has a good plan that will win you the game when you execute it well. What does this deck look like?

Creatures (8)

Lands (18)

Spells (34)

I came to this list after several conversations with Gerry Thompson and Sam Black, both of whom have been interested in Opposition in conjunction with Young Pyromancer and Lingering Souls. Their insight, as always, was indispensable.

This is a proactive Deathrite Shaman deck. It seeks to get ahead on board early by leveraging Deathrite Shaman’s mana production. It wants to start casting multiple spells per turn with Young Pyromancer in play, so it plays 30 instants and sorceries. When half the deck triggers Young Pyromancer, you can have some explosive turns.

If everyone’s favorite two-drop doesn’t show up, though, you also have Lingering Souls to help build a board presence. But since the deck has twelve cantrips to dig to a Young Pyromancer, it will generally cough one up before too long.

The card that sets this deck apart from every other deck in Legacy is its 2UU four-drop. Every other blue Deathrite Shaman deck in Legacy plays Jace, the Mind Sculptor. This deck plays Opposition. Let’s talk about why.

|

vs. |

|

Jace, the Mind Sculptor is not particularly good right now. It is certainly an objectively powerful card, but there are many contexts in which Jace underperforms.

Against Delver decks, Jace can’t Unsummon a Nimble Mongoose or Geist of Saint Traft. It gets Lightning Bolted a lot. It gets Dazed or Spell Pierced or just stranded in hand due to Stifle and Wasteland.

Against Deathrite Shaman decks, Jace gets attacked a lot. Between Baleful Strix, Shardless Agent, Deathrite Shaman, Dark Confidant, Stoneforge Mystic, Creeping Tar Pit, Tarmogoyf, and Vendilion Clique, there is no shortage of creatures with which to harass a Mind Sculptor. Many of them are particularly miserable to Unsummon yet also miserable to kill with a removal spell. Jace can excel in some situations, but it is prone to dying a quick death in others.

Against combo decks, Jace is often a four-mana Brainstorm on the turn before you die. I have often rejoiced while playing Omni-Tell when a Deathblade player taps out on turn 4 for a Jace, as the only card I have to worry about from them at that point is Force of Will. The Unsummon ability is a blank, and the fateseal ability is very rarely relevant.

Against aggressive decks, Jace dies. A lot. When it doesn’t die, it’s usually because the aggressive player is ignoring your Jace and just killing you instead. There are games where your dinky creatures protect Jace long enough for repeated Brainstorms to carry you to victory, but those games require a lot of things going right.

Opposition is different. Opposition is a card that can come down on turn 4 and win the game on the spot against combo decks. It can Rishadan Port them for the rest of the game in conjunction with your many, many 1/1 Elemental tokens. If your opponent puts an Emrakul or Griselbrand into play, your Opposition does not care.

If your blue midrange opponent casts Stoneforge Mystic, the ensuing Batterskull Germ will likely never attack through an Opposition. Creeping Tar Pit is similarly embarrassing against a free Icy Manipulator. It is easy to tap their team at the end of their turn, untap, and kill a planeswalker.

So how do Opposition and Jace line up head to head?

Against Delver tempo decks, Opposition is roughly as bad as Jace, except it can ensure that your creatures "trade" for their non-shroud threats. In the intervening turns, you can stabilize the board and take over the game. In many similar spots, Jace would just die to a single hit from Nimble Mongoose.

Against Deathrite Shaman quasi-mirrors, Opposition is an incredible trump. It doesn’t get Abrupt Decayed. Maelstrom Pulse is seeing less play in Jace decks now that there is a need to kill their Jace while not killing your own. Vindicate is rarely played and only in small numbers.

Spell Pierce is a similar rarity, as the blue midrange decks either play Shardless Agent (precluding the possibility of sleeving up Spell Pierce at all) or rely on Flusterstorm for its added power against today’s combo decks. Golgari Charm is effective against Opposition, but that sees only sideboard play in one deck.

Many of the cards in this deck that are traditionally very bad against combo—Lingering Souls and Young Pyromancer—are made excellent by the addition of Opposition. Souls and Pyromancer are natural predators of planeswalker-based midrange strategies, attrition-based control decks, and small aggressive decks. Opposition also shines against large aggressive decks, as Tarmogoyf and its ilk can be indefinitely detained by a single Spirit apiece.

Now that I’ve told you why Opposition is a well-positioned card, let’s go through how we can maximize the strategy behind it.

Our game plan against aggressive decks is to set up a board presence, take some damage, and stabilize with creature tokens and removal, using Opposition to lock down their real threats while generating more tokens to start attacking. After sideboarding, we want to cut cards that are very low-impact or have a bad rate for cards that they have to answer (ideally with cards that they wouldn’t normally want against us).

Our plan against midrange decks is to ignore the card advantage created by Ancestral Vision or Stoneforge Mystic and present an unkillable trump card in Opposition to lock down their mana for the rest of the game. Their board presence will be insufficient to carry them over the finish line before we can make more tokens to shore up our position. After sideboarding, our game plan stays roughly the same, but we want to focus even more on staying ahead on board.

Our plan against combo decks is to accept a bad matchup in game 1, rely heavily on an early Opposition to Armageddon them, and aggressively deny them access to main phase mana while hoping that Force of Will is good enough. After sideboarding, we want to cut our removal for more counterspells and discard. Our three-pronged approach—attack mana, attack cards in hand, and attack spells—should give us access to critical decisions on which resources are important. If we can correctly identify and deny a combo deck their most important resource, we will win.

Our sideboard should include cards that augment those strategic approaches while remaining relevant in other matchups.

The Maindeck

Eighteen lands: I’ll get back to the specific lands, but this is a deck that wants to cast spells with its lands. Since it’s playing all five colors, we aren’t going to do anything cute. We aren’t playing Wasteland, we aren’t playing Creeping Tar Pit, and we aren’t playing Mishra’s Factory. We’re playing fetchlands and dual lands. We don’t want the 22-24 lands of Shardless BUG or Esper Deathblade, though, since we have so many more cantrips. We have Ponders and Probes where they have more expensive cards, so our curve is a lot lower. We’re going to see more cards over the course of the game, so we will end up finding enough lands. We’ll revisit this more in depth in a bit.

4 Brainstorm, 4 Ponder, 4 Gitaxian Probe: Any Young Pyromancer deck that is serious about making tokens should be playing all twelve of these. Their power level is off the charts, they chain together well, and they allow you to play some situationally powerful instants and sorceries without having to cast them in matchups where they’re poor.

4 Young Pyromancer: The backbone of the deck. Pyromancer pays us off better than anything else for the cheap spells we already want to play. It’s not worth playing other cards that exist in a similar space—Dark Confidant, Delver of Secrets, Snapcaster Mage—because Young Pyromancer creates the most value if left alone for one turn.

What happens if they don’t kill Delver for a turn? They take, on average, two damage.

What happens if they don’t kill Dark Confidant for a turn? They take two damage, and you draw a card.

What happens if they don’t kill Snapcaster Mage? They take two damage, but your added value is realized immediately and through a removal spell.

What happens if they don’t kill Young Pyromancer? You make, like, four tokens and go down a card in hand. Maybe you resolved a Lingering Souls. They’re almost certainly behind on board now, and they have to decide between killing Pyromancer and playing something to block.

If you start shoving Delver and Snapcaster and Bob into your deck to get paid off from all of your spells, though, you’ll have to cut spells to get those cards in your deck. Inch by inch, you’re getting paid less and finding cards that want to get paid more.

I prefer the volatile economics of Young Pyromancer; yes, sometimes you won’t have something paying you to cast Ponder, but at least you have room for all the removal and cantrips that you want in your deck.

3 Opposition: The win condition of the deck so to speak. It asks a question of its controller on every turn of the game: "what matters right now?" Maybe it’s your life total, and you should tap their creatures in the beginning of combat step. Maybe it’s board presence, and you should tap their lands. Maybe it’s their life total, and you should tap their creatures on their end step. With every new piece of information, the answer to that question can change and so can your evaluation of how to best use your creatures.

Opposition rewards long-term planning and careful research. If you know what your opponent is capable of, you can play around almost anything. If you’ve seen your opponent’s hand, you can sculpt a game plan that best stymies theirs. Opposition figures prominently in all of these schemas.

It’s impossible to tell you exactly how to play with Opposition, but a good starting rule of thumb is to not trade off your creatures unless you must. You have a lot of removal in your deck to handle their creatures. Once Opposition lands, their creatures will no longer feel threatening. Your creatures are an excellent resource—consider their value not just in the present but in the future as well.

The one-mana removal spells (4 Swords to Plowshares, 2 Lightning Bolt): Plow and Bolt are the two best creature removal spells in Legacy in that order. They are the best because they cost one mana, have the fewest conditions about what they kill, and have the most negligible drawbacks.

This deck wants a lot of cheap spells. It also wants a lot of removal spells, as its goal is to survive long enough to present a lockdown control endgame via Opposition. Since the deck wants to play a lot of spells to trigger Young Pyromancer, it can’t play a lot of creatures to trade with other creatures. As a result, it has to play an above average number of removal spells.

Deathrite Shaman is another reason to focus on playing more one-mana removal spells. This deck wants to stay ahead of an opponent’s development, and Deathrite Shaman is a huge problem for that strategy. Kill it on sight.

Swords to Plowshares is more valuable than Lightning Bolt because Lightning Bolt’s upsides—going to the face and killing planeswalkers—are less meaningful in a deck that isn’t racing and whose strategy is naturally very strong against every currently played planeswalker. An opponent’s life total rarely matters, so Swords to Plowshares doesn’t really have a drawback. Given how annoying a Tarmogoyf can be, it is advisable to play all four Plows even though they are dead cards against combo decks.

4 Deathrite Shaman: This is a Birds of Paradise that can be cast off of Underground Sea. Everything else is upside.

4 Lingering Souls: This card’s rate is too good to ignore. Lingering Souls out-attritions planeswalkers and dinky little creatures while teaming up with Opposition to take out more impressive threats. If you asked me to line up four cards that tell the deck’s story, they would be Deathrite Shaman, Young Pyromancer, Lingering Souls, and Opposition. The full dozen blue cantrips are implied by Young Pyromancer naturally.

4 Force of Will: This deck taps out a lot. It also has a lot of blue cards. Two of its blue cards—Gitaxian Probe and Opposition—have diminishing returns, which is to say that drawing the second copy of either is worse than drawing the first copy. Force of Will mitigates that drawback by allowing you to remove the second copy from the game to make your counterspell free.

Force of Will is a far better option than something like Flusterstorm, which would require you to lower your shield in order to play your spells on curve. It is a far better option than Daze, which has a number of meaningful drawbacks in this deck; it’s worse on the draw, it’s dead in the late game, and it hurts your mana development when you want to be playing multiple spells in a turn.

You want to have Force of Will in your maindeck to have a fighting chance against fast combo decks. If you can defend with Force on turns 1 through 3, your game plan revolves around resolving an Opposition and sort-of Armageddoning them for the rest of the game. While Force is pretty poor nearly everywhere else, it’s good enough against combo that you want all four in your maindeck.

1 Quiet Speculation: This is deceptively powerful. Quiet Spec looks like a sixtieth card, but it actually informs the deck’s last five slots. Being able to draw Speculation lets us play several packages in our deck. For combo, we can get:

Lingering Souls

Cabal Therapy

Cabal Therapy

And combined with the information from Gitaxian Probe, you can disrupt a combo deck enough to land Opposition and lock them out of the game.

If you’re fighting an attrition battle, you can get:

Lingering Souls

Lingering Souls

Battle Screech

And put six tokens into play for only four mana. While Battle Screech would otherwise be fairly suspect, the existence of Quiet Speculation to entomb it allows you to play it as a fifth Lingering Souls. Considering how good the first four are, Battle Screech is still good enough to make the starting team.

Finally, Quiet Speculation lets us buy a critical turn against an aggressive deck after sideboarding with our solo Moment’s Peace.

2 Cabal Therapy: I went over the dissonance between discard spells and other game plans in my first Young Pyromancer article, but it’s worth reviewing. Here are the takeaways:

First, ask yourself how you’re going to interact with them. "Everywhere" is not an acceptable answer. Your game plan should be focused. For instance, a tempo deck wants to kill opposing lands, making their cards in hand useless. A Rock-style deck wants to make an opponent discard cards, making their lands useless.

This deck is focused on "killing" opposing lands with Opposition. If you execute your game plan successfully, they won’t cast spells any more. At that point, you’ve virtually Mind Twisted them—it doesn’t matter that they have cards if they can’t use them.

Cabal Therapy works at odds with that plan, and it’s important to acknowledge that before I talk about why I still want to play it.

I want to play Cabal Therapy as a way to buy time. I only want to Therapy critical cards: an Umezawa’s Jitte off of Stoneforge Mystic, a High Tide from a Time Spiral player, a Show and Tell from an Omniscience player, and so on. The point is not to put together a discard package that will consistently shred their hand. The point is to deny them an important spell on the turn before they need it.

After sideboarding, Probe/Therapy/Pyromancer is a valid plan of attack, but few decks are vulnerable to that plan. As a result, two Cabal Therapys start off in the sideboard, and they come in rarely.

1 Battle Screech: As I mentioned earlier, the fifth Lingering Souls. The worst card in the deck and worth questioning. If you pointed a gun at my head and told me to figure out how to make the deck better, it would involve cutting Battle Screech. For now, I like having a lot of token makers.

1 Intangible Virtue: Sam wanted two, and I can’t blame him. The different between 1/1s and 2/2s in a world of Shardless Agents and Deathrite Shamans is enormous. When my videos go up, I may end up having made the intuitive swap of -Screech, +Virtue. For this article, I wanted to lay out the maximum range of options that this deck has available.

The Mana Base

I have never built a fetch-dual five-color mana base in Legacy before, so this process was fairly involved. I started by figuring out which colors are most important.

Blue is the deck’s primary color, as it acts as the mana-fixing color. Brainstorm and Ponder can attempt to fix the mana, so casting those is very important.

Black casts Deathrite Shaman, flashes back Lingering Souls, and casts Cabal Therapy. It makes sense to emphasize this a bit . . .

But white casts Swords to Plowshares, Intangible Virtue, and the front end of Lingering Souls. If part of our removal-heavy plan is to kill early Deathrite Shamans, we need access to turn 1 white . . .

But the same goes for red since we’re also playing Bolt to kill Shaman. In addition, we have Young Pyromancer to play on turn 2 or 3. Fortunately, that’s the extent of red, so it’s clear that we don’t need a ton of red sources.

Finally, green is just for Deathrite Shaman’s activated ability. The Moment’s Peace in the sideboard is a total freeroll off of the existing green mana.

How does this all come together?

It’s clear that we want a lot of fetchlands since we can mostly count those as sources of any color. We also want to consistently activate Deathrite Shaman, so playing at least ten is a good idea. We don’t know what exact colors they’ll be, but we do know that blue is our primary color. We should expect to play a lot of blue fetchlands since nonblue fetchlands will miss some of our blue duals.

We want fourteen sources for Deathrite Shaman. I remember hearing Zvi Mowshowitz talk about how you need that many sources to cast a turn 1 mana accelerant, so I’m going with that. That means we need four dual lands that make black or green mana.

We want fourteen blue sources for Ponder and Brainstorm. That’s how many RUG Delver plays, and I wouldn’t mind more if we can fit them.

We want eleven red sources for Young Pyromancer. Again, RUG Delver plays eleven green sources for Tarmogoyf, so I’m fine extrapolating those numbers over since it also plays eleven red sources for Lightning Bolt and expects to cast that on turn 1.

We want eleven white sources for Swords to Plowshares, using the same Lightning Bolt logic as above.

We want one green land in the entire deck because the second one is terrible to draw if the first one gets Wastelanded. Since we’re unlikely to fetch green early and since any Wasteland wielding opponent is likely to immediately Stone Rain us given our color requirements, I’m not worried about getting cut off of green mana.

So we’re assuming that we’ll have ten fetchlands and eight dual lands. Let’s start by adding one of each blue dual since those are all completely fetchable.

Four slots left.

Now it gets harder. We’ve fulfilled our mana requirements, but we want to find ways to operate off of two lands as well as possible. For instance, if we Ponder and fetch, what land casts the most time-sensitive spells in our deck?

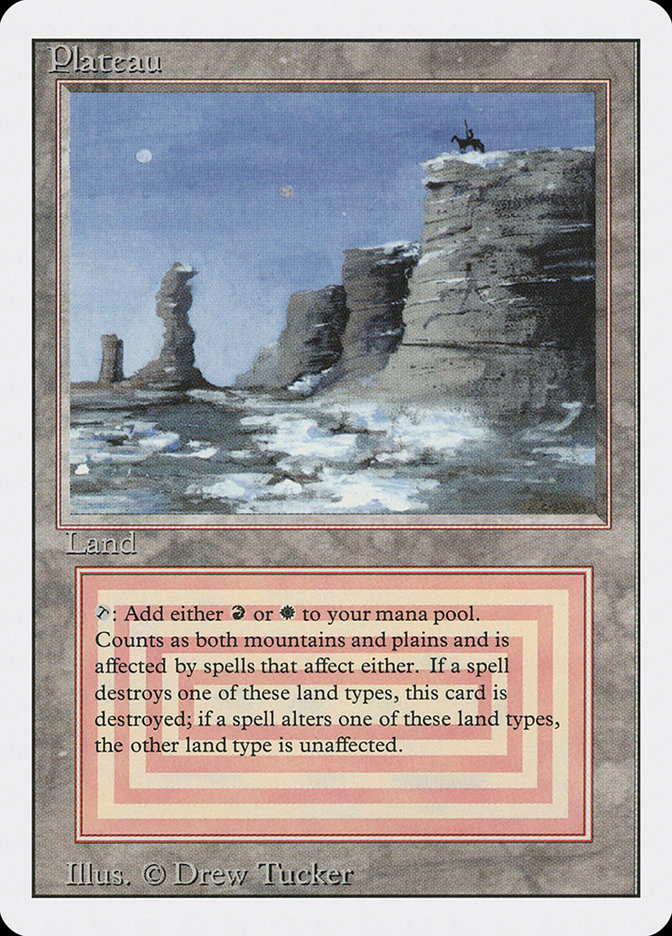

Plateau casts Swords to Plowshares and Lightning Bolt. It also casts Young Pyromancer in a world where we got Underground Sea on turn 1 in order to cast Deathrite Shaman.

Three slots left, and I’m feeling a little better about casting removal spells early.

This was the point where I threw together a sideboard and decided to emphasize black over other colors in sideboard cards.

If Underground Sea and Plateau are a good pairing, I also want to be able to Brainstorm and fetch into the next-best nonblue dual.

Scrubland[/author]“][author name="Scrubland"]Scrubland[/author] casts Swords to Plowshares and Cabal Therapy as well as both halves of a Lingering Souls. It plays well opposite Volcanic Island, which is a big plus.

Two slots left, and we’re short a Deathrite Shaman source.

We want to augment our blue sources and need a Deathrite Shaman source, but we’re not playing a second green land, so a second Underground Sea is in order.

One slot left, and a count of fifteen blue, thirteen black, thirteen white, twelve red, and eleven green.

The problem is that nothing fetches every blue dual as well as Scrubland[/author]“][author name="Scrubland"]Scrubland[/author] and Plateau, so we’re actually shorter than advertised on some of the secondary colors. Since we have all of our blue fetchland requirements fulfilled, I decided to add an eleventh fetchland. Since we have two nonblue duals that make white, it makes sense to have it be a white fetchland. Since we want it to be able to cast Deathrite Shaman, it should get black mana as well.

One Marsh Flats, and we’re mostly done.

What should our blue fetchlands be?

Our best fetch land is Flooded Strand, as it gets both Scrubland[/author]“][author name="Scrubland"]Scrubland[/author] and Plateau while also getting all of the blue duals.

Scalding Tarn and Polluted Delta each miss one of the nonblue duals, so we can split those.

This leaves us with:

4 Flooded Strand

3 Scalding Tarn

3 Polluted Delta

1 Marsh Flats

2 Underground Sea

1 Tundra

1 Volcanic Island

1 Tropical Island

1 Plateau

1 Scrubland[/author]“][author name="Scrubland"]Scrubland[/author]

It’s a process, as you can see.

The Sideboard

Since this deck plays all five colors, the sideboard options are nearly limitless. I built the sideboard to emphasize minimal colored mana requirements since it’s not always possible to guarantee a specific dual land configuration in play. All of our sideboard cards should therefore have a maximum of one colored mana. Instead of just picking the sweetest cards possible, I tried to build the sideboard to maximize the competencies of the maindeck while also allowing for clean swaps in commonly played matchups. What does that look like?

Against combo, I want to cut at least all of the Bolts and Plows. There should be six clear-cut anti-combo cards in the sideboard.

Against a lot of other decks, I want to cut the Forces, Therapys, and some Probes. If they’re a creature deck, I want to bring in removal. If they’re a grindy midrange deck, I want to bring in more enchantments that beat them. If they’re a tempo deck, I want to lower my curve and disrupt their cantrips.

I knew early on that Flusterstorm would be a four-of in this deck’s sideboard. It fights combo and tempo decks very well, and it counters the types of cards that we want to counter the most.

The last two Cabal Therapys were also early locks, as being able to turn into a Probe/Therapy/Pyromancer deck is appealing against combo.

From there, my choices were a hodgepodge. I wanted cards that would lock out aggro, so I added two Jittes of my own. I wanted cards that would be tough for midrange decks to beat, so I added Bitterblossoms. I wanted my tokens to be better in sideboarded games since all of my plans revolve around having them in play, so I added another Intangible Virtue. I wanted to get cute with my last slot, so I added Moment’s Peace.

When you have this many options for what to put in your sideboard, it’s important to adhere to specific selection criteria. I articulated mine above, the cards fit those criteria while also being some of the best cards in the game at what they do, and they swap in for other cards pretty intuitively.

Does that make my decisions right? Not at all. There isn’t anything close to "right" in this situation. It is important to understand what you are trying to do on a macro level when building a sideboard, but creativity is rewarded within those frameworks. I am sure there are ways to improve on my ideas.

Do I still stand by them? Absolutely.

And I look forward to showing you the deck in action next week with more Legacy videos. I’ve enjoyed learning more about recording, and I appreciate your feedback and patience while I’ve been careening through this Camtasia crash course. As always, I welcome your comments.

Until then,

@drewlevin on Twitter