I started playing U/W Control in the most recent cycle of Standard because I lost to U/W Control at a PTQ.

I’d been working on the list for a long while already, and when William Jensen placed second in Dallas-Fort Worth with a U/W Control list built by Andrew Cuneo, it started a conversation at work. Brian Kowal came into my office asking, “Did you see Huey’s list? It looks a lot like yours!“

At the time, I was still preferring my aggressive red list that splashed white for Boros Charm, but I had “2-QUICK UW control.dek” on Magic Online as my secondary deck, and it was relegated to the bench when I was out trying to win events. I’d done quite well with the deck, winning a $5K tournament, but at that moment, Esper was slowly being eclipsed by U/W Control, largely because of decks like Jensen’s. The final straw was a first-round loss to a younger player playing a non-Elixir list that was very different than Jensen’s list, and thus also not much like I would have built the deck.

Thinking about what Kowal had to say, Kowal was right: my deck was a lot like Huey’s. I had an extra Jace where he had a Divination, a single Essence Scatter where he had a fourth Dissolve, a Celestial Flare where he had a single Ratchet Bomb, a Cyclonic Rift where he had an Azorius Charm, a Mutavault over Jensen’s Island, and finally, I had an Aetherling where he had a second Syncopate. Ultimately, the biggest real difference was that I had two finishers where Jensen ran only one – well, that’s not quite correct. We both ran an Elixir of Immortality as well, and that is a card you might want to count in that slot. Having 55 of 60 in the main in common and 67 of 75 in common with a deck he so successfully piloted made me go back to the deck to revisit it. The original was even closer, with me choosing a fourth Azorius Charm over a Cyclonic Rift.

Here is that early version, published a few weeks before Jensen’s win:

Creatures (1)

Planeswalkers (5)

Lands (26)

Spells (28)

Looking at the list, I can see so many of the ideas in my list from almost six months ago live on in the list I’m currently playing. Right now, I’m incredibly happy with where I’m at with U/W Control, and don’t know that I expect to change a card of the 75 since this past weekend, where I took second in Milwaukee with it.

During the coverage, Patrick Sullivan and Cedric Phillips had a lot of great things to say about me and the list, but one of the points that they talked about repeatedly was my use of “fun-ofs” – singleton copies of cards in the deck. Aside from just being one-of cards, I think a lot of these cards that they referred to as “fun-ofs” were also cards that were a little off of the beaten path.

In one match, the semifinal match between me and Jerrett Rocha, these fun-ofs were extremely evident, in large part because we were both playing Elixir of Immortality, and so the games could go quite long (his build was Esper). Here is that match, starting at the thirty-minute mark:

Watch live video from SCGLive on TwitchTV

Here is the list I played at SCG Milwaukee, (12 cards different in the main, and 4 in the side from my earlier published list):

Creatures (1)

Planeswalkers (5)

Lands (26)

Spells (28)

Now, one thing I could do is talk about the specifics of each of the many card choices, and make this article about this deck. But even though winter is going, we do have Journey Into Nyxx coming so soon that it feels like it might be much more valuable to use the deck as a means to talk about what is possible in constructed by using the deck as an example. Understand that, for the purpose of this article, I’m talking about what is possible for singletons specifically in a Sphinx’s Revelations/Elixir of Immortality shell. So, let’s get to it…

Making Sense of Singletons

The idea of a single copy of a card in a deck as potentially a problem has been in the game for a very, very long time. If you think about it, it makes sense, on a basic level of analysis: if a card is good enough, why not run more?

Here was their argument, as I discussed it many years ago:

For a long while in Magic, an idea had emerged that good decks were decks that looked like this. Four copies or one copy was the norm, with a few exceptions that were explained away. This idea became advocated pretty heavily by very influential people. A big part of why I wrote “Overcoming the 4-1 Dogma in Numbers” is that this idea was taking hold as a kind of orthodoxy, despite the fact that it wasn’t a useful way to build decks, in my opinion, so much as a shortcut to something that was often correct. To me, plateaus of thinking like this aren’t useful in creating greatness, only in creating “good”-ness.

Understanding why certain numbers are useful is important. I went into this in even more detail in my article “One”, which talked about understanding when a copy of a singleton makes sense.

They are:

1 – As Tutor targets

2 – Inevitability

3 – Analogs

4 – Diminishing Returns (and more)

On Tutoring

While I go into it in a lot of detail in One, I’ll say a little here about tutoring, even though in Standard there are only a handful of instances where this happens. A singleton might make sense when you can tutor – if you have the ability to search your library, you might only need one copy. In U/W Control, this can happen with Jace’s Ultimate, but is not generally a reasonable factor in deciding whether or not to include a singleton: at the point where you’re using Jace’s Ultimate ability, you’re probably in the driver’s seat.

On Inevitability

Inevitability is a much bigger thing to reckon with in Standard, and actually an incredibly important thing to understand in relation to singletons. The concept of Inevitability was coined by Zvi Mowshowitz over ten years ago, and it is a way to understand which player will win from the current position given a long time horizon. One of the reason that U/W Control and Esper Control are so good is that they will generally have inevitability in most matchups. If the game continues onward, you will bury an opponent under Sphinx’s Revelation. This is even more true when you’re also running Elixir of Immortality. The game will continue in such a way that Sphinx’s Revelation will find you more card draw (in the form of Sphinx’s Revelation and whatever else), and then the Elixir will just supply you an endless loop of cards.

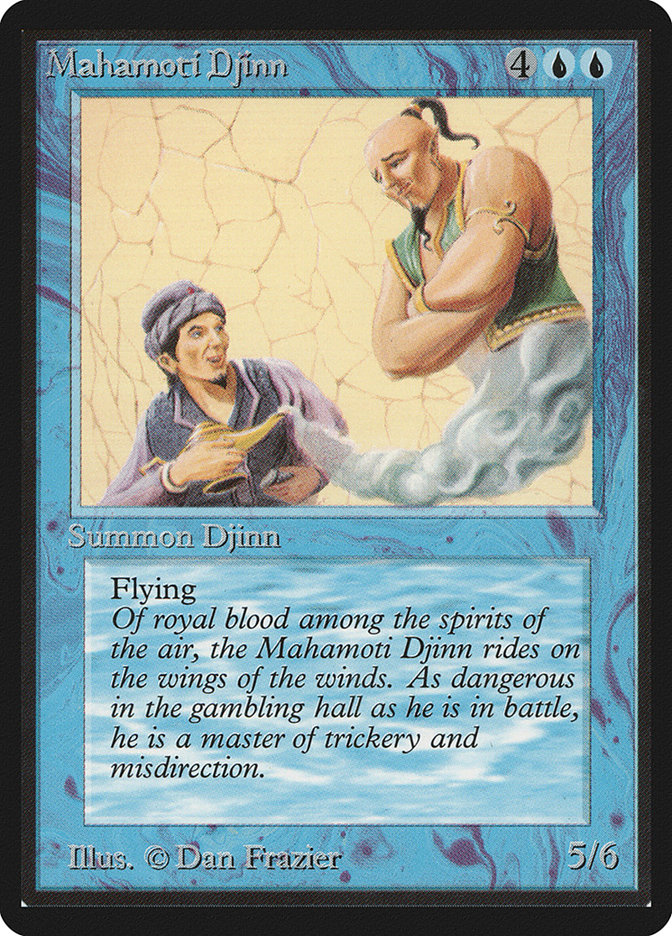

The question of Inevitability is exactly why I personally love the Elixir builds. You can build inescapable games where an opponent can’t hope to just bleed you out of resources, because the loop of resources is never-ending. The concept of this is something that I first started working with in my old classic deck Baron Harkonnen, a U/G Control deck from 1997 that eventually moved from a Soldevi Digger base into a Gaea’s Blessing base. Patrick and Cedric talked about this a little in their coverage of SCG Milwaukee (Patrick saying generously of me that I was playing “the archetype that he’d invented” was him making reference to the Baron from way back). The Baron, as a deck, was completely dedicated to simply not letting the opponent win, and only had one “true” win condition: a single Mahamoti Djinn.

As crazy as it sounds, these cards are basically the same thing. At the end of the game, you’re going to kill them with something . Back when Mahamoti Djinn was legal, it was practically impossible to kill easily (though Swords to Plowshares was a thing), but if you managed to, it didn’t really matter because The Baron would just use a Gaea’s Blessing to bring it back. Aetherling hits harder and it is harder to kill, but in the context of their respective eras these are basically the same card. And in the context of what a deck that has Inevitability wants, they are ideal: they will close out a game generally very rapidly, and be hard to handle.

It is worth recognizing, then, in these Sphinx’s Revelation/Elixir of Immortality decks, that the very nature of your deck is one that isn’t just going to go to a long game, the whole game plan is to have the ability to go to a very, very long game. In fact, that is the entire idea of deck’s that have this Baron Harkonnen-like philosophy – a kind of Baron-Theory – you can build your deck to exploit it. With this kind of plan and with access to the kind of card draw that you have, high-impact and seemingly narrow singletons can actually thrive. Each of the following cards can actually be placed in that category (however loosely we want to define “narrow”):

In order to be worthy of inclusion in the “justified by Inevitability” category, it has to be a card that it won’t matter if it comes into the game on turn eight or on turn twenty. If you’re still alive and kicking and that singleton could turn things around, it could very well be justifying its place. Remember, Inevitability isn’t a justification for any old card. You could say, for example, “Colossus of Akros and Gorgon’s Head are the perfect 1-ofs for the late game! Inevitability!” You still need to be making rational card choices. Inevitability is just a way of understanding that you will find the cards, because your deck is designed to give you sufficient time to do so. Once you understand that, you might find yourself with a reasonable justification for any number of cards as a singleton.

Just remember, to fit the Inevitability justification, they need to powerfully impact the game, be rational cards in an expected potential game state, and not need to be drawn at a particular moment in the game (since you can’t know when you’ll acquire it). It is a part of the very nature of Sphinx’s Revelations/Elixir of Immortality.

On Analogs

The idea of analogous cards is an old one. If you don’t know it, it basically says that some number of cards are basically the same, and so mixing and matching can have value. It used to be that the 4-1 purists would view the use of analogous cards as heresy (“one of those cards is the best one so find out which one!”), and they are at least correct that sometimes there is simply a best choice. But take this:

For Mono-Black Devotion, which one is the best? The answer is, “it depends”.

As you go through your testing, you might even determine that one is better than the rest. I believe, for example, that Owen Turtenwald currently views Devour Flesh as the best of these cards, but either way, let’s say for the sake of argument that Devour Flesh is the best of these and you choose to run four copies. If you actually need five two mana removal spells, you might end up with… a singleton! If you need six you might end up with a two-of, but if you can’t really come up with a clear front-runner between second- and third-best, splitting the difference is certainly an acceptable choice up until you determine that one card is more necessary than another.

It is worth noting that in the Baron-theory Sphinx/Elixir decks, it is definitely better to have a split than to have two copies of a card that hasn’t clawed out a space for itself in the deck. The versatility of the other kind of card will make a difference over an infinite time horizon, and it matters. The life gain from a Last Breath will be something you can randomly have access to in a game one, but only if you have it in your deck.

This is a part of the reason for a counterspell split of Dissolves and Syncopate and Essence Scatter in my build of the deck, and even more after board. I love Dissolve, but I’d rather have access to another different kind of effect than a fourth Dissolve or a fourth Gainsay in the board. The cards can help justify each other because they act like another card, but they bring something else to the mix that you can leverage if need be.

Subterfuge is another real power of analogous singletons. When you see, for example, a sideboarded deck run six different counterspells against you, it starts to become difficult to imagine what they might be capable of in any single turn. If you’ve planned out a turn for the potential fight against a Dissolve and two Gainsays and have worked in how a Syncopate might fit in the mix, an Essence Scatter might just ruin your plans.

In my particular build of U/W Control, here are the analog groups that are formed with singletons, sometimes with non-singletons:

Aetherling

Elspeth, Sun’s Champion

Jace Memory Adept

All of these cards can close out a game.

Azorius Charm

Celestial Flare

Cyclonic Rift

Disperse

Last Breath

Essence Scatter

Syncopate

Ratchet Bomb

All of these cards can function as early game removal (albeit the counters being “pseudo-removal”).

Detention Sphere’s role with Disperse is incredibly varied, but the two cards in combination often make Disperse act like a “fifth” Detention Sphere.

Cyclonic Rift

Fated Retribution

Elspeth, Sun’s Champion

Debtor’s Pulpit

Supreme Verdict

Each of the first three cards can serve as a high-impact removal spell, in many ways backing up your Supreme Verdicts – or in the case of Debtor’s Pulpit, accentuating it.

Dissolve

Essence Scatter

Syncopate

Negate

Render Silent

Gainsay

Disperse

Cyclonic Rift

As was discussed earlier, these each have a different impact on a game. Having access to “counterspell” is valuable. The bounce spells are in this group because they can let you have another chance at countering a spell that snuck through.

There are far more analogous aspects between the cards, and thus we can make a lot of different comparisons. I think you get the idea, though, about the ways in which analogous cards get to function in ways that make them more “singleton” than singleton.

Just remember, to fit the analogous justification, you really need to have access to enough cards that make similar effects, and there can’t simply be a card so much better at the job that you should simply be using it. In addition, the differences between the cards should open up the possibilities in lines of play that might not have existed without it.

On Diminishing Returns (and more)

Some cards just get worse with company. Legends and planeswalkers often have this problem, with your extra copy often being a “backup” copy unless the card either uses itself up or can get rid of the extraneous copy. While these two card types are the most dramatic example of this, other cards also have this quality as well.

Take the inclusion of Elspeth, Sun’s Champion in non-Elixir builds of U/W Control and Esper. Elspeth is an incredibly powerful card, but by the time you start looking at the fourth copy the planeswalker element of the card is getting in the way of itself. Perhaps these non-Elixir decks would run four if it wasn’t for the rule about unique planeswalker names.

For something not rule-limited, check out this deck from Milwaukee:

Creatures (8)

Lands (23)

Spells (29)

Why only two Boros Guildgate? Why only three Shock? Why only two Chained to the Rocks in the main? Why only two Burning Earth in the board?

The simplest answer is that more copies comes at too high of a cost. For the R/W Burn deck piloted by Liszka, having better mana would be great, but at the opportunity cost of having more lands enter the battlefield tapped he decided it wasn’t worth it. Chained to the Rocks is similarly problematic, as it slows down your ability to mobilize a kill, even if you might need it. Shock is low-impact enough that while you might play some, you’d rather cut the card to make room for something else than play another – this is the reason I only run two Azorius Charm in my U/W list. Burning Earth in the board is great, but at four mana it can sometimes be too slow to come to the party, and sometimes you just don’t want to drop it at all because you have things that need doing now.

There are simply diminishing returns to adding more copies of some cards.

When I introduced the idea of diminishing returns as a Magic concept over six years ago, I used an example from Judgment-era Standard, my Grand Prix Milwaukee deck including three copies of Price of Glory in my sideboard. Price of Glory greatly exemplifies diminishing returns because its effect is one that doesn’t increase with additional copies in play.

I still feel the same way as I did when I wrote about it then:

The first Price of Glory is absolutely incredible against a counterspell deck. The second? Not so much. While clearly the card is a card that you want to see against them if you get one out you mostly don’t want to see another copy. For a card to escape this problem it has to be so damning on its own that it warrants extra copies. Cards like Worship Choke or City of Solitude are such complete hosers that it can be worth the extra copies that might be “dead” in multiples. Other cards often lack that virtue. Price of Glory was absolutely a card that I would be excited to bring a single copy of from the board against numerous matchup (with other analogs) but I will never again run multiple copies of it unless somehow a deck exists that transforms it into a complete hoser.

A great example of a card that is powerful enough to play many copies of even though they don’t do anything extra is Blood Moon:

This card is so good when it is good that you don’t even care if you have extraneous copies. Price of Glory, on the other hand, is quite powerful… but not nearly so powerful that you can afford to draw any extraneous copies.

In my U/W Control deck, there really isn’t a card that is as dramatic as Price of Glory in its diminishing returns. Blind Obedience certainly has some major diminishing returns, but at least an extraneous copy does something. One of the typical results of the effect of diminishing returns, however, is that you start viewing the second copy of a card that you might even desire as less valuable than the first copy of another card. Given our usual goals of reaching 75 cards between maindeck and sideboard, sometimes even a card you’d like to have more of ends up at one because the diminishing returns on the next copy placed it as the 76th card in the mix. Diminishing returns is probably the biggest reason you only see one copy of Elixir of Immortality in a deck that can be so defined by the use of the card: the second one simply doesn’t give back nearly enough.

Applying this concept can be demonstrated in the selection of bounce options in my deck. When I was first started working on the deck, I had Cyclonic Rift, and I was largely okay with it until one day I realized that Disperse was just the better card. I wanted to be able to target my own permanents, and the tricks with Detention Sphere were too important. It was incredibly good to the point where I was considering a second copy. However, the second copy simply wasn’t giving enough back. You can afford to throw away a card on a bounce spell in this deck because you’ll plan on making it up later. The second Disperse just ended up feeling ever so slightly not good enough. It wasn’t until I was trying to figure out whether I could afford to include a second Fated Retribution that I remembered my old friend Cyclonic Rift.

It was the perfect inclusion. It functioned very much like a second Disperse, but because it also had the Overload ability, it didn’t end up having that same diminishing returns problem. The fact that it was also analogous to Fated Retribution at the same time just helped it out incredibly.

Just remember, in order to fit the diminishing returns criteria, the loss in value of extra copies of the card has to be big enough that you can get more value out of other cards. Many times this can be hard to quantify, and this justification is the one most likely to be able to spur debate among whomever you might have working on a deck.

Forward

I’m excited to be able to play a deck that feels so powerful. All told, there are a lot of singletons in my deck – nineteen, in fact, after counting the sideboard as well! That said, unless something dramatic happens to the metagame I’m planning on playing the exact same list again the next chance I get. I expect that that will be at the Open Series in Detroit, but we’ll see.

On the horizon, we have Journey into Nyx coming out in just a few weeks which is sure to shake things up. For some decks, perhaps it will have all of the impact of Born of the Gods on Sam Black’s version of Mono-Blue Devotion. For other decks, perhaps it will only create the same impact we saw in Mono-Black Devotion. Then again, perhaps we’ll see something more dramatic.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this discussion. Since my finish at Milwaukee, I’ve been asked to give a seminar on Magic. I have plenty of ideas for what I might cover, but I thought I’d ask all of you. If I were to give a talk on Magic, what kind of talk would you find exciting?

Let me know. If someone else suggests it, don’t worry, I won’t mind if you chime in “I second that!”