Darth Vader is Luke’s father.

I know!

I know!

I’m the king of spoilers. Good friends have unfollowed ye olde @fivewithflores on Twitter because I have—often inadvertently—spoiled some aspect of some television program (usually Lost).

But Stephen Colbert recently revealed that audiences generally enjoy a show more when they know the ending, believe it or not!

In that vein, I’m going to give you the core takeaways of this article up front (which has grown like a fungal infection—a beautiful, sprawling, but still itchy—fungal infection):

- One way to win incremental games (games you would otherwise not win) is to expand your conception of the scope of the terrain,

- Gitaxian Probe’s ability to produce near-perfect information rewards strong players disproportionately; but all players can benefit from understanding Gitaxian Probe’s mysterious ability to fix opening hands, and

- "about 40%"

Well, there you have it; not one ending but a count that would give The Return of the King a run for its tremulous box office money. If you want to stop now, "you’re welcome" for the incremental games; if you want to know not just where we ended up but how we got there, I invite you to read the next ~3,000 words.

LOVE

MIKE

Part I: Why Anyone Does Any Asshole Thing, Ever

My baseline assumption is that most people are doing the best thing they can. I think that most people—when they fail, when they act out, and so on—are not actually "bad people" but that they have a limited view of the terrain.

Let’s consider the average negative comment on a forum:

If you’re the victim of a baldly negative, seemingly directionless comment, the first thing that you might ask yourself is, "Why?" Why would someone write this thing? Heck, the first word of this section is "why!"

Asking why is especially tempting when you 1) know you’re right or 2) are doing something that provides actual value to your customer and/or can help them win incremental games. Neeman’s Lost in the Woods article is a great example. He’s awesome, his strategy was eye opening, and I know from mailing lists I’m on that include multiple PT Champions that someone got some pretty good learning and incremental wins from this line of thinking.

My current working model is that the best Magic articles help readers/players win incremental games; that is, games that they wouldn’t otherwise win.

When you post a format-breaking decklist, that’s the easiest example of when you can help someone win incremental games. It’s hard to imagine a more perfect storm than when Marijn Lybaert posts a deck, Tom Martell grabs it and tweaks a little bit, then takes down a Grand Prix. That’s hella obvious.

However, imagine the B/U player who plays Go for the Throat rather than Doom Blade because you suggested it as a solution to Grave Titan. Now when the game’s close and he’s on the draw against Grave Titan in the metagame-unexpected B/U mirror, and the opponent taps for Grave Titan… He basically has to deal with two 2/2s (no big deal). Especially as he’s going to himself tap for what will be an uncontested Grave Titan (opponent is gripping Doom Blade, LOL).

And if he has Consecrated Sphinx? Go for the Throat gets that, too.

When a top operator teaches you a new bluff or even a new way to approach the process of deception, that can pay off down the line as well.

That said, you don’t necessarily have to be "right" in order to be useful or to help someone else win incremental games. You can go down some kind of well-thought-out discussion and end up in the "wrong" place but still plant the seeds for some future success, so long as the other party is sufficiently broad-minded.

Hopefully—when you get to the third part of this here article—we’ll have even more tools for the winning of incremental games.

End aside.

That said, the reality is that "why" is one of the least useful and least satisfying questions you can ever ask, especially when there’s no good answer.

"Why"—in the face of a situation with no answer—just forces someone (maybe the bad actor, who will inevitably not have a good answer) to invent some bs reason why he did whatever awful thing. I know this from business more than I know it from Magic or writing, and believe me, it’s useless and unsatisfying. "Why did you make this horrible bid/targeting decision/budget stretch/etc.?"

Often the answer has to do with 1) aesthetics (GOOD LORD, AESTHETICS ARE YOU KIDDING ME WE SPEND MONEY HERE—unbelievable, but true), or, more likely, 2) the bad actor simply had a bad map. Either they didn’t know the correct technique or the limits on their breadth of authority (mismatch between map and terrain) or they were scared of do-nothing repercussions (wanted to show activity without necessarily a strong understanding of results…again a map/terrain mismatch).

Typically there’s no good answer to the question "why," so we should relegate any such to simply a bad map.

So what do I mean by "bad map?"

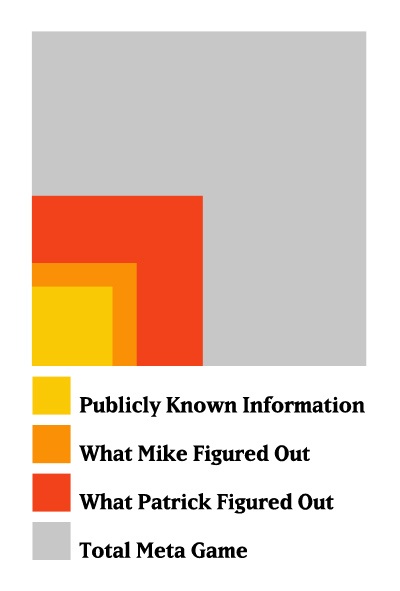

No one person has a perfect understanding of "the terrain" (you can define "the terrain" as whatever is being discussed…anything from the metagame to the economy). Most people operating under "bad map" limitations only see a small subsection of the entirety of the terrain but treat that imperfect understanding (i.e., their "maps") as everything.

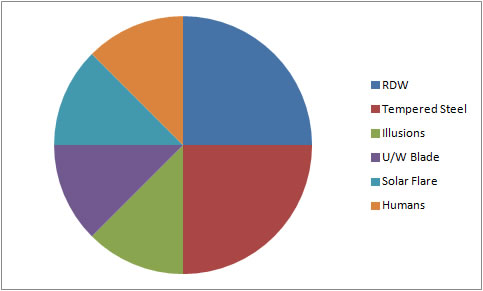

Let’s say it’s early in the Innistrad Standard format, and our early SCG Open Series Top 8 results show us this:

- RDW

- Tempered Steel

- Illusions

- Solar Flare

- U/W Blade

- Humans

You can take this information and chop it up in a couple of different ways. The simplest is to see it based entirely on Top 8 populations:

You can go read some articles and shift your opinion based on initial impressions and the commentary of so-called experts. At this point in the metagame, there was a discussion about how many copies of Hero of Bladehold were appropriate in Tempered Steel and a question about the appropriateness of Mana Leak in Solar Flare. Was Mono Red a real thing? Was Todd’s Illusions deck a fluke? Ridiculous? The format-breaker? All or none of the above?

Most tournament players will simply take one of the first two maps of the metagame, possibly informed by the subsequent paragraph (and discussion around the ‘verse), and make an evaluation with the following, startling assumption:

This is unbelievable if you lay it out like that, but that’s the reality of what must be going on in players’ heads to be making such bad metagame decisions as they constantly do, week after week, tournament after tournament.

The reality is that this is what most metagame models really look like:

Consider Brian Sondag world-warping breakout performance with Wolf Run almost immediately after that first Top 8.

He figured out Slagstorm and Tree of Redemption to keep himself alive against beatdown (including the reach of red decks), Ancient Grudge to completely bury Tempered Steel (and we can see how valid these competing strategies would remain come Junya Iyanaga’s complete annihilation of the ChannelFireball resurgence of Tempered Steel despite their amazing 4/8 Top 8 performance), and a complete out-class of Solar Flare not just on the cards, not just "the matchup," but the very battlegrounds of cross-strata and imagination.

Most Solar Flare opponents could not even imagine the requisite gameplay to avoid getting completely blown out, let alone win a match. I was in the SCGLive booth when I saw Jonathan Medina stumble and throw away a Doom Blade that could’ve been his lifeblood…as well as the valiant confusion of discipline, strategy, and good fortune that allowed Christian Valenti to out-last Sondag one game by drawing both of his Doom Blades and all of his Snapcaster Mages.

Wolf Run Ramp against Solar Flare in the early goings was actually a wonderful mismatch of map and reality for Solar Flare opponents. That is, Sondag’s overwhelming wave after wave of lethal threats revealed just how inadequate the average control player’s map of the terrain was.

Listen to Patrick Chapin Brewmaster’s Delight.

I agree wholeheartedly; and again, drawing on my marketing background would argue that the most effective people in the world are "wrong" anywhere from 50-90% of the time. Up to ninety percent!

The difference between them and the rest of the world (i.e., the merely mediocre to the actively atrocious) is that they quickly figure out where they are wrong and stop doing that thing; then they take action and scale up the 10-50% of the areas where they are right.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned in an adulthood largely devoted to Magic: the Gathering, it’s an ever-deepening respect for people with strong statistical skills and an overwhelming revulsion at how bad most people are at math. I previously thought that the greatest barrier to human progress was dogmatic thinking limiting technological advancement, but after seeing a certain Congressional proposal circulating Facebook I have come to the realization that we’re never even going to get to answering that question if we allow well-intentioned low-EV decision makers to plunge not just themselves but everyone into an economic Dark Age easily 3x worse than 2008 with no horizon for something like 30 years.

End aside.

Takeaway from Part I:

One way to win incremental games is to expand your conception of the scope of the terrain.

Not one of us has a map that truly conforms to the terrain, whether that’s "the Standard metagame" or "the term and magnitude of bank liability related to student loan debt" let alone "the entire US economy;" however a basic acceptance of our limitations is the first step to broadening our horizons in a sufficient scope to win even one more game (let alone a Premier Event).

When I interviewed Tom Martell for Channel: Dumbo Drop, I thought very carefully about what to omit. There were a lot of opportunities to rag on friends and antagonists alike who were critical of Tom’s deck choice and the card Lingering Souls in particular. I think you might be shocked at some of the players giving the old butter thief the beats for that; but we ultimately decided that winning was the best revenge.

That said, just think about what some of those players could’ve gained by expanding—rather than further contracting—their maps of the true terrain of the Legacy metagame.

Part II: What We Can Learn from the Number One Card

My favorite card from New Phyrexia—as advertised both above and in the referenced article—was/is Gitaxian Probe.

In preparation for this weekend’s SCG Open Series: Baltimore featuring the Invitational, I’ve tested dozens of tournament queues on Magic Online. My best EV deck is actually my own four-color Reanimator deck (more or less here), which has won about 2/3 of its matches (in contrast to Frites where I’ve never failed to lose to Curse of Death’s Hold + any other card in tournament play).

That said, even though Reanimator has been my mathematically strongest deck, I resolved to play a Gitaxian Probe deck for a couple of reasons:

- My win percentage with Gitaxian Probe decks is limited by my own play skill, which has improved from the outset.

- Gitaxian Probe decks—in particular U/W Delver—most closely conform to my best working model of success in deck design, outlined here.

- The SCG Open Series featuring the Invitational is a high EV event where, unlike a Pro Tour, I actually have an edge on play skill; the presence of Gitaxian Probe in its ability to provide near-perfect information rewards me disproportionately to other strategies.

Now in one of my tournament matches, I found myself tempted to submit a first turn Probe to a certain blog featuring bad keeps revealed by Gitaxian Probe.

This was the reason (he was on the play):

Wow is that bad!

How could he keep?

His hand not just does nothing… He can’t cast anything!

I refrained, and ultimately extrapolated to this section of this article after applying my own model of map versus terrain. Does the keep look any better if we expand our map a little bit?

Well…what do we have here? A land in play! This hand is clearly a bit of a gambler, but even if he can’t Ponder or play any card but Gitaxian Probe there’s at least the evidence of some wheels turning. Samuele Estratti kept a very similar hand against Jon Finkel in the #PTDKA video coverage, and though it seemed awful from the outset, he actually "got there" to win.

Oh wait… Perhaps I should expand ye olde map a little bit more:

What’s it that we have here?

Two more Gitaxian Probes in the graveyard?

All of a sudden this hand looks quite a bit less speculative than the previous two iterations. The next question becomes, "Why stop at two and settle for a Plains"? All of a sudden we move from a hella-judgmental "that was an obvious bad keep" to "I guess it isn’t as bad as I thought" to actively "I might have kept that one myself."

The reason I didn’t submit the screen shot in total was twofold: 1) I realized that I would’ve just been the same kind of gleeful asshole I spent all of Part I criticizing, and 2) I didn’t want to reveal the opponent’s name. Because you have heard of him, and he’s probably better than you.

Takeaway for Part II:

Gitaxian Probe’s ability to produce near-perfect information rewards strong players disproportionately; but all players can benefit from understanding Gitaxian Probe’s mysterious ability to fix opening hands.

Part III: How to Play with Gitaxian Probe in Your Opening Hand

In the above game, I easily smoked [NAME REDACTED], as he had no lands. I’ve found a sound sideboard strategy for the Delver mirror and easily won game 2, but like I’ve spent the last 16 years hammering into readers’ heads, that’s actually irrelevant.

What’s actually interesting is our ability to use information to form arguments and improve our process and technology.

The first "asking better questions" question we should ask is: how does having Gitaxian Probe in your opening hand affect keeping a speculative hand?

And because [NAME REDACTED] actually had two Gitaxian Probes in his graveyard (we can’t actually know if he had the Plains and/or whether he had both Probes in his opener if not all three), there’s a more practical corollary question: did he do the math? Wait a minute? WTF IS THE MATH?

-Michael J. Flores, "Gitaxian Probe and the Answer to Everything"

Let us assume a Delver deck of the Costa model with 21 lands. 21 lands means that 35% of your cards are lands. A Standard U/W Delver deck draws on the Comer-Xerox principle like no other deck since 1997, and the Costa deck plays:

The Comer-Xerox in general says that "for every four one- and two-mana cantrips in your deck, you can remove one land;" in theory, Costa’s deck then plays 26 lands, which is a hearty amount for most any deck and certainly one with such slender CMCs.

We’re going to be a bit more precise with our evaluation here and limit our discussion to the effect of particular cantrips on opening hand evaluation, specifically to address [NAME REDACTED]’s decision… Hot or not?

Let’s assume you have a seven-card hand with no lands.

Most players would toss this hand away most all of the time regardless of deck, and it’s easy to understand… Such a hand, despite being flush of seven cards, is like having no hand at all if you can’t cast anything. But in the Costa deck, with its incredibly low CMCs, powerful (and cheap!) threats, and four Gitaxian Probes, shipping the no lander is anything but a foregone conclusion. Who hasn’t at least thought about keeping a hand with a Probe and a Delver (or three?), dreaming of the unstoppable turn 3 attack for nine?

Only someone who hasn’t played enough Delver.

But how justifiable is this, actually?

Let’s do the easy math first. You have a Probe. How likely are you to hit a land if you Probe once?

This one is pretty easy. You have (60-7) cards in your deck, and all 21 lands are still there: so the answer is 21/53, or about 40%.

If your question is, "How likely is my no lander on the play to hit a land when I have one Gitaxian Probe in grip?" you have your answer of "about 40%"…which is what I slotted in the initial takeaways. You realize, of course, that this is a completely useless answer—not because it’s wrong—but because the question is pointless.

Very few players in contention are going to weigh their openers like that. Most of them are going to have some other kind of immediate action, like a Delver of Secrets or a Ponder they want to set up. The question in such a case should be more like, "How likely is my no lander to hit untapped blue on the play when I have one Gitaxian Probe in grip?"

If we assume:

4 Glacial Fortress

9 Island

3 Moorland Haunt

1 Plains

4 Seachrome Coast

…we have 21 lands, but four of them are complete whiffs (Moorland Haunt and Plains don’t cast Ponder or get you a second turn Insectile Aberration), and four of them (Glacial Fortresses) are near misses. We really want to go with two lines here, 1) workable (13/53) and 2) not-embarrassing (17/53).

Our chances of getting there—really "getting there" with our sick Delver follow-up or the Ponder that’s going to save our bacon without shipping to six—is only about 24.5%. What are your thoughts on hanging your fortunes on a one-in-four (actually a little less than one-in-four)?

Our chances of simply "not embarrassing ourselves" by including a trip to the Glacial Fortress increase us to 32%…less than one-in-three.

The first time I wrote about opening hand mulligan math on Five With Flores, GerryT did me a huge compliment, contacted me, and actually changed my mindset about how I approach these things. The question should never be just about whether or not you hit land/relevant land…but how likely you are to win the game at hand.

With one Gitaxian Probe in an otherwise no land hand—on the play—(we don’t have the benefit of the first draw and, for kicks, we don’t know what the other guy is)…how willing are you to rest your fortunes on:

- 40% – Some kind of land with no guarantee of being able to cast something

- 32% – Some kind of action, presumably, by next turn…again with no guarantee as Glacial Fortress is not immediately relevant

- 25%-ish – Being able to make a play (but still no guarantee at a next land)

Wow, that’s bleak, right?

Not really.

It’s all a matter of balance. The real question should be "which is greater, the 32% of the time my Delver deck has ‘some kind of action’ against an unknown opponent" or "the likelihood I can beat the same unknown opponent with six cards?"

Notice how we spent all that time on the math but then shifted the entire map to a completely different region of the terrain, a speculative new six, and a heretofore interaction with the unknown?

We can actually do this forever and extrapolated against a bazillion decks. But here’s the math for this case, and you can think about how reasonable it was for [NAME REDACTED] to keep in the spot he did, assuming no land but two Probes:

- We know he’s about 40% likely to hit "a land" on the first Probe. That means that he’s about 60% likely to not hit a land.

- If he doesn’t get there the first time, he’s 21/52 likely to hit a land (same number of lands but one fewer card in deck)…which is also about 40%, or 60% unlikely to hit lands.

- That means that 80% of the time he will hit a land, right? 40% + 40%? GOD NO!!!

- 40% of the 60% he will hit a land. We can add that to the 40% from #1 above to get to an overall 64% likelihood of hitting at least one land with no lands, seven cards, and two Probes. Of course based on the Plains [NAME REDACTED] ended up with, we know that that ~2/3 isn’t necessarily what we should’ve been focused on; in fact, while he’s in very good "one land" shape after 3-4 draws (Probe or however), he’s not guaranteed a land for more than 20 repetitions!

- Three draws (remember he had three Gitaxian Probe) puts him to a whopping 79% to hit at least one land (which he did); possibly Plains was good enough, and he didn’t want to go down to 14 life with the opponent’s archetype unseen; after all, he had another two pulls coming for turn 2, which would have put him on Mana Leak and/or Snapcaster Mage mana (and Snapcaster Mage had plenty of free fodder to play with).

If you’re curious, the probability of drawing a second land (after the Plains) using the third Probe and your first draw step is 63.5%. If you’re only interested in drawing an untapped blue source, that goes down to 56%.

Hopefully this section has given you the tools necessarily to extrapolate to other common situations that come up all the time (but please remember GerryT’s paradigm as you go about your business).

LOVE

MIKE