My two favorite tools to work with in Magic are burn spells and countermagic.

I think I probably first started falling in love with these cards right from the very beginning of my time playing

Magic. The summer before I headed off to college, I swapped out my white-bordered Counterspell and other countermagic for the newest version of

the art, a rare thing for me, since I always preferred just running the older art.

I don’t remember all of the cards that were in that old deck, but it was about 90 or 100 cards of pure awfulness, in retrospect. Thankfully for all of us,

early Magic tends to be all about awfulness, and my level of awful was on par with the awful that all of my friends were at. When I got my first real lessons into how bad I

was, this was an incredible opportunity for growth; I still think that

Paul Rietzl is right when it comes to how we make mistakes: we’re all bad. The good thing about this is in how it can humble us and let us learn

moving forward.

One of the things that I’ve definitely put deep into my wheelhouse is figuring out Burn. How it functions isn’t entirely unique, but it does have a lot of

important characteristics that make it just a bit different than other decks.

The most important of these is how being able to interact directly with an opponent’s life total can entirely let you sidestep a traditional Magic fight

over card advantage (or economy) and tempo. When I came up with

this idea back in 1999, I didn’t know Mike Flores would name it for me: “The Philosophy of Fire”. Now, I might not care for the title, but it is

a useful umbrella for understanding that our relative closeness to being dead (something I like to call our Health) puts intrinsic pressure on our ability

to make decisions. In fact, we leverage a healthy life total all the time.

For example, in my U/B Control deck, I might decide versus Abzan Aggro to take a hit from several creatures to drop myself to eight life, and then at the

end of the turn, activate my Perilous Vault. If you drop my potential life total to three life, I would make entirely the other decision, not wanting to

put myself at risk of a Rhino now or a Rhino tomorrow. In between, at four to seven life, the decision to take the hit or not can become much more

difficult.

The choice that is being decided here is a question of turning one’s life total into an active resource that you can leverage into better options.

It may well be the case that your opponent would have nothing to follow up with if you just blew up this hypothetical Perilous Vault immediately, but

unless they accidentally show you their hand or they empty it before combat by laying their last card in hand down, the decision to defer is something your

life total can afford you.

Being Healthy gives you options.

Or, conversely, a lack of Health removes them.

Take this recent successful Standard deck:

Creatures (15)

- 1 Frenzied Goblin

- 4 Foundry Street Denizen

- 2 Goblin Rabblemaster

- 4 Monastery Swiftspear

- 1 Lightning Berserker

- 3 Zurgo Bellstriker

Lands (20)

Spells (25)

Martin Dang’s Atarka Red deck is a very aggressive red deck that largely relies on attacking to get in its damage. In fact, here are the non-attacking ways

the deck can create damage:

Sixteen burn spells may sound like a lot, but this still doesn’t make this deck Burn.

A deck can be thought of as being of an archetype (or, on a grander scale, a strategic archetype) not based on how it behaves in any moment, but in how it behaves in the grand collection of all

of the moments a deck has altogether. To put it another way, just because your deck beat down with creatures that one time, it doesn’t mean that

it is a beatdown deck.

And so, Dang’s deck might get in a little bit of damage against an opponent and then burn them out for, say, sixteen damage, but that doesn’t mean it is a

Burn deck. More typically, Dang is going to attack for a lot of damage, and the burn will be there to help finish an opponent off, while the vast majority

of the deck works via the attack phase.

The Third Axis

Now, a deck is not better or worse for existing on that third axis of Health (where the Philosophy of Fire lives) as opposed to card advantage and tempo.

In fact, attacking is one of the most efficient ways to deal damage. There is a good reason that Wild Nacatl was such a widely-played card. Wild Nacatl was

often very capable of just dealing a hell of a lot more damage than any single burn card

However, if you played with Wild Nacatl, that damage was going to be working in direct interaction with the majority of opponents’ cards. Can they kill it?

Can they block it? A lot more cards in Magic are prepared to interact on this fundamental level than are prepared to be interacted with on the level of

discard and countermagic.

Furthermore, when damage is immediately having an effect on someone’s life total, you can be quickly pushing someone to the point where they don’t have the

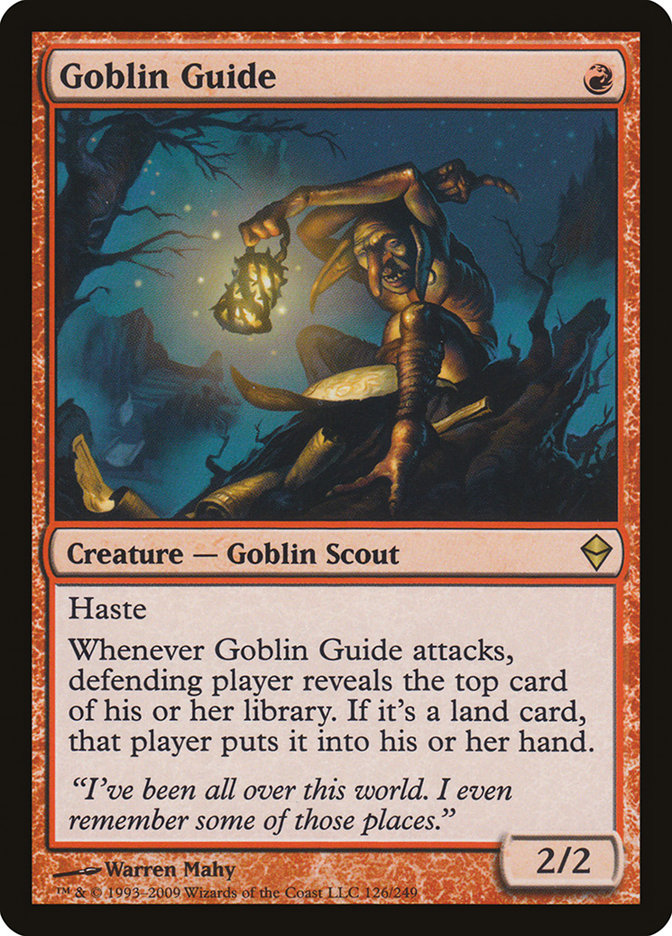

ability to make good decisions. One of the best cards in Burn decks of all formats is also one of my favorite cards of all time:

Can you believe that when this guy was printed in Zendikar, some very excellent Magic players called the card nearly unplayable? It definitely

blew my mind. I knew that as soon as I saw it, I was talking with my friend, fellow red-lover Ronny Serio, about how insane the card was. Like a Wild

Nacatl, the card could get in for a lot of damage. Unlike Nacatl, though, many times, that first hit of damage would be completely unstoppable, because

your opponent wouldn’t have even put their first land into play.

If you have enough cards that create damage pressure on your opponent without their ability to interact conventionally, now you have a Burn deck.

This kind of pressure does strange things to an opponent’s ability to make choices. If your opponent is about to enter turn 2 and they are having to

consider whether or not to take damage from an Overgrown Tomb or Steam Vents, it is because they are respecting the volume of cards that can directly

reduce their life total, not necessarily by turn 3 or 4, but even as late as turn 6 or 8.

That two life now might be the game later.

One of the reasons that we see Burn as an archetype in Modern, specifically, is because there are actually enough cards that you can put directly into

attacking an opponent’s life total now that you can create enough of those “moments” I was talking about earlier to

have that be a consistent gameplan. In Standard, (for now) there simply aren’t enough of those cards for Burn as a strategy to work; instead, you will find

yourself using burn cards to help out an attacking strategy.

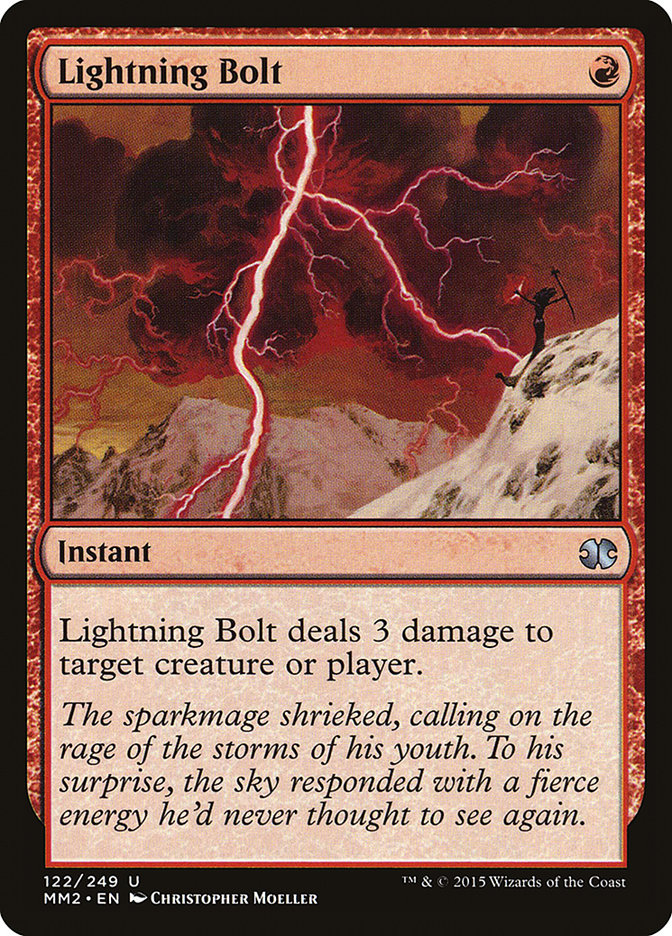

Now, just because you happen to have Goblin Guide and Lightning Bolt, this doesn’t mean that you are a Burn deck, though.

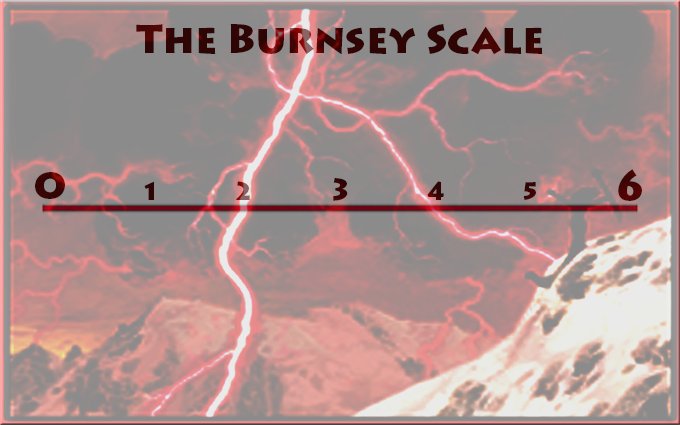

Let’s imagine a scale of decks with those cards, where on one end of the scale, you are decidedly not a Burn deck, and on the other end of the

scale, you are decidedly a Burn deck. Because I’m a former (recovering!) academic, I’ll set this scale from 0 (for non-Burn) to 6 (for Burn), and

give it a name, say, “The Burnsey Scale.”

Now, if we imagine every deck with Goblin Guide and Lightning Bolt living on this scale, that vast majority of them are not going to be 0 or 6. A deck that

is a 0 (“not Burnsey at all”) is probably out there somewhere, and a deck that is a pure 6 (“completely Burnsey” – with practically nothing that can’t deal

damage immediately) is also probably out there, but most decks with both Goblin Guide and Lightning Bolt are likely to live a little closer towards the

center, at 1s and 2s or 4s and 5s.

Examples of Burnsey Scale Ratings

Now, I named this scale somewhat farcically, but it remains that there is a large range between decks that are Very Burnsey and Not-So-Burnsey.

Take this deck, which is probably somewhere around a 1 on the Burnsey Scale:

Creatures (32)

- 4 Kird Ape

- 4 Tarmogoyf

- 4 Wild Nacatl

- 4 Goblin Guide

- 4 Flinthoof Boar

- 4 Burning-Tree Emissary

- 4 Experiment One

- 4 Ghor-Clan Rampager

Lands (18)

Spells (10)

Now this list is over a year old, and the world is a little different than it once was, but, it illustrates the point. This deck does have a tiny bit of

burn and even some pseudo-burn – Ghor-Clan Rampager usually will be used with bloodrush, and while that use is essentially “only” as a pump, in practice,

this particular card somehow often feels a lot closer to a burn spell than a pump spell.

We can step a little closer to being Burnsey, going up to somewhere around a 2:

Creatures (28)

- 4 Kird Ape

- 4 Tarmogoyf

- 4 Wild Nacatl

- 4 Goblin Guide

- 4 Burning-Tree Emissary

- 4 Experiment One

- 4 Ghor-Clan Rampager

Lands (20)

Spells (12)

Now, we’re less than a year back and this Zoo list packs those Ghor-Clan Rampager, but it also adds the Ghor-Clan-combo with Boros Charm, in addition to

just being able to use Boros Charm as a pseudo-counter or as a straight-up burn spell. We’re still not in the land of Burn decks, but we’re getting closer.

If we hop back in time, we can see a deck straddling the exact middle, Prosak Zoo, from Extended circa 2009:

Creatures (20)

Lands (22)

Spells (18)

Goblin Guide wasn’t quite around yet, but I thought this was such the Platonic Ideal of what I meant, I had to share one of Adam Prosak’s most influential decks. We’re up into the realm of

26 cards that immediately dealt damage, all backed up by the “best Lava Spikes,” Wild Nacatl and Tarmogoyf. If Goblin Guide had existed in that moment in

time, it is easy to imagine it making the cut here.

Something similar can be said for this Boros deck which 4-0’ed a Modern Daily just the other day:

Creatures (16)

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (22)

Spells (20)

Sideboard

This deck has Monastery Swiftspear in the place of Goblin Guide, but as far as the Burnsey Scale goes, this is probably close to a 3–almost directly in

between doing damage now and building up a force coming on in to attack.

If we’re going to move directly into the realm of the truly Burnsey but still be in the business of attacking, my current experiment in Burn is worth

checking out:

Creatures (21)

- 1 Grim Lavamancer

- 4 Keldon Marauders

- 4 Goblin Guide

- 4 Vexing Devil

- 4 Ghor-Clan Rampager

- 4 Eidolon of the Great Revel

Lands (19)

Spells (20)

Sideboard

This is a wild departure from what I think is the norm right now for this archetype. It is largely based on the fact that I’ve had bad experiences so far

with Monastery Swiftspear in Modern. I decided to go a little retro with my version of the deck, and one thing led to another, and here’s where I’m at.

I’m not suggesting that this is a great deck (yet); what it is is a good example of a deck that is, perhaps, a 4 or so on The Burnsey Scale. This deck is

certainly fundamentally a Burn deck, but it is absolutely more invested in attacking than this archetype tends to be.

Here is another, quite different 4, but from a Modern Daily last week:

Creatures (15)

Lands (20)

Spells (25)

Sideboard

Finally, we have a 5 on The Burnsey Scale:

Creatures (14)

Lands (19)

Spells (27)

Caleb Griffin’s deck is a very straightforward build of the deck, at least in game 1. If you’re playing Modern right now, this deck is within one to three

cards of what the vast majority of Burn decks are going to look like, so this is probably an excellent candidate for use as a gauntlet deck.

What makes this deck a “5” instead of a mythical “6”? A deck that is basically pure Burn?

Well, this isn’t exactly a 6, but it is probably close to a 5.5 or so, to speak from a place of tongue-in-cheek abstraction:

Creatures (12)

Lands (19)

Spells (29)

- 4 Lightning Bolt

- 4 Lava Spike

- 4 Rift Bolt

- 1 Shard Volley

- 4 Searing Blaze

- 4 Skullcrack

- 4 Boros Charm

- 4 Atarka's Command

Sideboard

This deck has practically nothing that doesn’t directly hurt an opponent. It’s actually quite hard to build this deck without some element of dedication to

the attack phase, but that’s basically because Goblin Guide and Monastery Swiftspear are just so darned good. The fact that they can get in before

an opponent might be able to respond can make them often act very similarly to a burn spell, thus bringing us ever closer to the fabled “6” of The Burnsey

Scale of Burn decks.

The Practical Elements of The Burnsey Scale

Ultimately, what makes a deck good isn’t where it sits on the scale so much as a deck being unified in what it is doing.

For example, let’s take a second look at that “1” on the Burnsey Scale again:

Creatures (32)

- 4 Kird Ape

- 4 Tarmogoyf

- 4 Wild Nacatl

- 4 Goblin Guide

- 4 Flinthoof Boar

- 4 Burning-Tree Emissary

- 4 Experiment One

- 4 Ghor-Clan Rampager

Lands (18)

Spells (10)

This Zoo deck is pretty dedicated to attacking.

If we just shoved Lava Spike and Skullcrack into this deck, it would cease to be the deck it wants to be. What do you cut to make that work? Every single

cut pushes the deck away from its identity at “1” towards the more Burnsey side of the scale at “6,” but it doesn’t mean that the deck is still a coherent

deck.

If Skullcrack were instead Atarka’s Command, there actually is a very reasonable reason to go that direction; Atarka’s Command works with

a deck that is trying to swarm, and it can be a very effective means to finish out games. That is the kind of change that might make sense.

Similarly, if we revise my earlier deck…

Creatures (21)

- 1 Grim Lavamancer

- 4 Keldon Marauders

- 4 Goblin Guide

- 4 Vexing Devil

- 4 Ghor-Clan Rampager

- 4 Eidolon of the Great Revel

Lands (19)

Spells (20)

Sideboard

…and we try to make it more conventional by adding in a missing card…

…there isn’t really a reasonable way to just drop it in. Do you cut a creature? Okay, well, if you do, you’re still dealing with a deck that has “only”

twenty actual spells, when most decks of this type are running 27 or more. You can run your Swiftspear, but they aren’t going to perform as well as they

would in another deck. If you actually cut spells from the deck to fit in the Swiftspear, you’re probably heading for the worst of all worlds.

Finally, why don’t we just add in a great spell to Burn?

Why don’t we just pop in this bad boy?

Again, imagine cutting a card from Caleb Griffin’s deck:

Creatures (14)

Lands (19)

Spells (27)

Quite literally any cut we make in the deck (except for land) is going to move us closer to a “0” on The Burnsey Scale in a deck that isn’t at all equipped

to take advantage of the resilience and power of a Tarmogoyf. Any single step towards letting our opponent interact on the framework of card advantage and

tempo is going to weaken our ultimate goal: reduce their Health (life total in this case) now so that their options are reduced to nearly nothing.

“And then,” to quote a friend, “you win.”

Magic is far more complicated than simply playing the best spells. Far more important is to play a coherent deck, even if you are playing this:

… over this:

What’s Next?

I’ll be seeing you in Las Vegas and Charlotte for the two Grand Prix. Burn is still on my radar for Charlotte, so don’t be surprised to see me charring

peoples’ faces!

See you there!