A firestorm erupted in the wake of my Ten Principles of Vintage article. The one and only Mike Flores questioned my claim that “Skill is King” in a format with, admittedly, the most forgiving and broken card pool. How can both claims be true?

To me, skill is about making optimal decisions. Putting aside for the remainder of this article those decisions that involve the psychology of the game, I think there are, broadly speaking, four basic categories of technical skill in Vintage: design options, mulligan decisions, in-game choices, and sideboarding.

That is not to say that bluffs, tells, and psychology of is not a huge part of the game.

Perhaps the most stunning play I have ever seen at a tournament was a direct result of brilliant mindf***.

It was round 8 of StarCityGames Power 9 tournament in Rochester, New York early summer of this year. The winner of this round would advance into the Top 8 for a guaranteed piece of power (a prize worth at least a few hundred dollars). The match was the Grim Long combo mirror. The players were Jimmy McCartney and Paul Mastriano, a.k.a. Mr. Type 4.

During the course of the day, Mr. Type 4 had built up a reputation for winning in a flashy explosion on turn 1. Jimmy was on the play. Jimmy looked at his hand. Paul looked at his hand and grinned. Paul inspected his hand and started to chuckle. Pretty soon the chuckle, accompanied by a beaming grin, became more of a belly-roll laugh.

Jimmy nervously inspected his hand. Paul shouted across the table: “Is it good enough?” Jimmy shifted his two land, Brainstorm, Duress, and draw7 hand around, thinking about whether to mulligan. After a moment of consideration, Jimmy found the hand too slow to win the combo mirror. Mulligan.

He pulled up a hand of six that had one Mox for a mana source. Back it went.

He pulled up a hand of one land and expensive spells. Back it went.

He pulled open a hand with no mana at all! Down to three.

Jimmy opened a hand without any mana. Down to two.

Jimmy kept a one-land hand.

Now the decision to mulligan or not passed to Paul, Mr. Type 4. To the great surprise of Jimmy, Paul mulliganed… into a gassy six-card hand that won on turn 2, which he did.

Paul used his earnest demeanor and his reputation for being a killer combo pilot with a penchant for turn 1 kills to win a game before it even began. It was the first genuine turn zero kill I’ve ever seen.

I say all of this as a way of saying what this article will not be about. It will not be about those psychological tactics that create in-game advantages. This would demand its own article. Some day, perhaps, but not today.

Design Skill

To even talk about design options is to bring deck choice into the domain of “skill,” in which it definitely resides. But when I say “design options,” I mean something more specific than simply deck choice.

Take a look at my original Meandeck Gifts manabase:

10 artifact accelerants (Black Lotus, Moxen, Sol Ring, etc)

1 Tolarian Academy

3 Underground Sea

3 Volcanic Island

3 Island

3 Polluted Delta

2 Flooded Strand

Now, imagine you are playing this deck and your opponent opens with this play:

Turn 1:

Opponent: Chalice of the Void for zero. Mishra’s Workshop, Crucible of Worlds.

Assume further that they are holding Wasteland.

You: You fan open your hand and you see: Mox Emerald, Underground Sea, Tolarian Academy, Brainstorm, Merchant Scroll, Gifts Ungiven, and Recoup.

You, sir, are screwed.

In the heady days of four Trinisphere, this play was not at all uncommon:

Turn 1:

Mishra’s Workshop, Trinisphere

Turn 2:

Tap Mishra’s Workshop, Crucible of Worlds for Wasteland recursion.

The opponent who brought a deck to the table with too many dual lands was devastated.

Trinsiphere was restricted, by Aaron Forsythe own admission, not because it was too good, but because it was unfun. To beat Trinisphere, you basically had to be a good player. You had to play one of three options: 1) You had to have a threshold number of basic lands, 2) you had to play Force of Wills or Wastelands or both, or 3) you had to have a really decent chance of winning on turn 1.

The problem is that too many – far too many, in fact – Vintage players play terrible manabases. They prefer the consistency of a high dual land manabase, and they get eaten alive by Wastelands.

Thus, here is my revised Meandeck Gifts mana base:

10 artifact accelerants (Black Lotus, Moxen, Sol Ring, etc)

1 Tolarian Academy

2 Underground Sea

2 Volcanic Island

5 Island

3 Polluted Delta

2 Flooded Strand

Sure, all I did was shift out two dual lands for two more Islands, but that single change makes all the difference in the world when facing Crucible Wasteland. It provides rock solid immunity and increases your ability to establish an early manabase. Vintage players make suboptimal design decisions all of the time. This, perhaps, is the biggest area where Mike Flores deep questioning of Skill is most persuasive. People run crappy manabases and play suboptimal decks because they can!

I hate to pick on Eric Miller, who I think is a skilled player, but I will. In the era of 4 Trinisphere, Eric Miller racked up what I think is still the most impressive number of SCG Power 9 first-place finishes ever assembled (I think he won at least three of these events). In each case, he did so with Workshop decks designed to abuse Trinisphere.

Take a look at “The Riddler”

Two fabricate? Hanna’s Custody? Two Juggernaut? WTF? How does any of that make sense?

If you sat down and played two-dozen matches with this deck against virtually any upper tier Vintage deck and you’ll be lucky to go 50%. Yet, what you will notice is that Eric deck is going to win the vast majority of its games using roughly 2/3s of the design choices. The power of 4 Trinisphere was such that it alone would account for many of the wins — slowing the game down enough to let other ancillary cards finish the job.

This is precisely what Mike Flores is critiquing: if you run cards like Mishra’s Workshop that can consistently power out turn 1 Trinisphere, doesn’t that, by definition, negate the claim that Skill is King?

This force of this critique is undisputed. It’s true. The power of the cards in Vintage make mis-attribution a very common effect. Here’s how it works:

Turn 1:

Mishra’s Workshop, Trinisphere

Turn 2:

Play a land, tap the Shop and the land and play Juggernaut.

Turn 3:

Play Crucible of Worlds and Wasteland. Swing with Juggernaut.

Three turns later, the game is over. Which card won the game? Juggernaut is the card that appeared to be the game winner to the pilot. But what if the opponent’s hand was this:

Gemstone Mine

Black Lotus

Mana Crypt

Mox Sapphire

Lotus Petal

Dark Ritual

Yawgmoth’s Bargain

From the opponent’s perspective, it was quite clear that Trinisphere was the lethal card. Such misattribution is very common in Vintage — it is obvious why. Perhaps the most egregious aspect of Eric deck is the combo of Illusionary Mask and Phyrexian Dreadnaught. It is unwieldy, slow, and frankly silly. Eric won a major tournament using it. There were probably a relatively nontrivial number of games where Mask-Naught early on won the game. There were probably games where he had one component, topdecked the other mid-game, and won as a result. There were even games, I’m sure, where he tutored up the other part. But what all that ignores is whether he could have won using other cards. The key cards — the Trinispheres and the Chalices — sufficiently slowed the game down that this fairly terrible win condition became quite viable. Turn 1 Trinisphere was so powerful, in combination with other random cards, that Mask-Naught, somehow, became serviceable. Every game that Eric won with Mask-Naught probably reinforced his mistaken view that this was a viable win condition. What it ignores is the counterfactual. Most players in Magic learn by losing.

We almost never ask “what could we have done differently” unless we actually lose. The very best players in Vintage rarely have to ask this question, and thus there is no real incentive to improve design in many respects. This is a serious problem.

I almost wholesale concede Mike Flores point within this category. Admittedly, Trinisphere no longer exists, but cards like Mana Drain, Tinker, and Yawgmoth’s Will obviate the need to have a perfect manabase more than they should, among other design suboptimalities.

Over the last year there has been some debate as to the optimal Control Slaver list. Michigan resident Brian DeMars has very much enjoyed playing his “Burning Slaver” list, which runs using Burning Wish and various “bot” choices. Similarly, Team Reflection’s Ben Kowal has become a forceful advocate for running a couple of Night’s Whisper in his Control Slaver list. Which is optimal? The truth of the matter is that mis-attribution is too powerful a force for us to actually identify the optimal list. As my friend Kevin Cron is fond of saying, “”Six of one, half-dozen of the other,” which means, roughly, that it’s all the same.

And yet, we cannot deny that Vintage tests design. It does. The best lists eventually make their way out. Over time – even over a long time – the best players lose games and modifications are made. As long as we understand and critique, we will find ways to optimize. I’m not even sure to what extent the design suboptimalities in Vintage differ from any other format. I’m hoping others can help us answer that question.

The Mulligan

There’s an old saw in Vintage. Something like “In Type One, the ‘early game’ is the coin flip, the ‘midgame’ is deciding whether to mulligan, and the ‘late game’ is turn 1.” As sad as that is, it’s really not far from the truth. But I would peg the early game as the mulligan and the mid game around turn 2.5, but that’s me.

The mulligan is huge. It is perhaps more critical in Vintage than any other format. So far as I know, in most other formats the decision to mulligan is primarily motivated by mana screw or some other serious defect of the hand.

Not at all so in Vintage. Mulligan decisions are intensely strategic.

Matchup knowledge is a huge skill in Vintage, and a fantastic hand in one matchup is garbage in another. Consider this potential draw from Uba Stax:

Mishra’s Workshop

Bazaar of Baghdad

Mountain

Wasteland

Goblin Welder

Smokestack

Crucible of Worlds

This hand could utterly tear up virtually any deck in Vintage — particularly Control decks and the Stax mirror. But sit down across from Combo, and this hand is utter garbage.

Imagine what Pitch Long would do to this hand. This hand has absolutely no threatening turn 1 play. The skilled Stax player knows that they must play either Null Rod, Chalice of the Void, Uba Mask or a card like Trinisphere on turn 1 or they might as well shuffle up for game 2.

But what if Stax got the utter nuts against combo:

Mishra’s Workshop

Mox Ruby

Null Rod

Chalice of the Void

Goblin Welder

Mountain

Bazaar of Baghdad

Only to sit down against Ichorid.

Imagine how the game might play out:

Turn 1:

Stax: Mishra’s Workshop, Mox Ruby, Chalice of the Void for 0. Goblin Welder, Null Rod.

Ichorid: Bazaar of Baghdad. Use it, discard Golgari Grave Troll, Stinkweed Imp, and Ichorid.

Turn 2:

Stax: Play Bazaar of Baghdad. Activate it seeing Tangle Wire, Trinisphere discarding them.

Ichorid: Upkeep, put Ichorid trigger on the stack. Activate Bazaar dredging Golgari Grave Troll revealing another Ichorid and an Ashen Ghoul as well as another Stinkweed Imp. Dredge a Stinkweed Imp revealing another Golgari Grave-Troll. Discard the Imp, the Troll, and another card. Remove a Black creature to put Ichorid into play. On my draw step, dredge a Golgari Grave-Troll revealing more dredgers.

Play a land. Attach with Ichorid, pass.

Turn 3:

Stax: do more irrelevant stuff — including putting Tangle Wire into play.

Ichorid: On upkeep, with Tangle Wire on the stack, put Ichorids on the stack, float a Black mana from your land, and dredge two Trolls. Use the Black mana to put Ashen Ghoul into play and remove two Black creatures to return two Ichorids into play.

Next turn, Stax dies. The Ichorid deck didn’t even have to play a spell.

If the importance of mulliganing isn’t yet evident, by god it should be.

Let me put it this way: Vintage decks are full of singletons. Control Slaver could open one game with turn 1 Tinker for Colossus, another game with turn 1 Thirst for Knowledge followed by Goblin Welder into Mindslaver recursion, and another game with Mox Sapphire, Island into a long, long control game.

You could open up three different hands with the same deck and result in very, very different opening games. You need to know whether you hand contains a viable plan in any given matchup.

Speaking now from personal experience, I think that the area in which I make the most match-deciding mistakes is the mulligan. Twice in recent memory I have taken my seat facing an opponent upon the belief that they were playing one deck when in fact they were playing another — in both instances it resulted in a game loss. The planning begins immediately in Vintage. The mulligan is a crucial part of the planning. You need to beat what your opponent threatens. The mulligan is a huge part of that.

This is a skill that is far more important in Vintage than other formats, so far as I am aware. The speed and power of the format only make this a more important and more potent skill. Thus, in this respect, the power of the format is consistent with the claim that Skill is King.

In-Game Decision Making

This is where the core of Mike Flores claim is being made. He argues, persuasively, that players mis-attribute the value of one card because it isn’t actually the finisher. For example, Pat Chapin claims that there is an extremely high correlation between resolving Ancestral and winning — that is, Ancestral will win the game unless answered by an equal “I win” card. The examples of other such “I win” cards that Mike gives are Gifts Ungiven and Yawgmoth’s Will.

I agreed that people mis-attribute, but I further claimed that the card that suffers from this phenomena the most is Black Lotus. As I put it:

Opening with Black Lotus is the most significant advantage that a Vintage player can enjoy. Yet, even more than Ancestral Recall, its value is misattributed to other cards. At least Ancestral seems to be doing something – Lotus lets you do other things.

The core of my claim or refutation of Mike Flores point, however, is that there are actually upward of sixty or so cards in Vintage that can just lead to the “I Win,” or negate other “I Win” cards.

That is really what Vintage is about.

Consider this play:

Turn 1:

Player 1: Land, Xantid Swarm

Player 2: Land, Ancestral Recall

Guess which player wins the game? Probably player 1.

Consider this play:

Turn 1:

Player 1: Forbidden Orchard, Mox, Oath of Druids, Chalice of the Void

Player 2: Land, Ancestral Recall

Guess who wins this game? Probably player 1.

Consider this play:

Turn 1:

Player 1: Black Lotus, Mishra’s Workshop, Smokestack, Null Rod

Player 2: Land, Ancestral Recall

Guess who wins this game? Probably player 1.

Or consider this play:

Turn 3:

Player 1: Tap a land Dark Ritual, Dark Ritual, sacrifice Black Lotus, Yawgmoth’s Will (or Mind’s Desire)

Response: Player 2 taps a land and plays Orim’s Chant.

Guess who wins? Probably player 2.

Even this play can win the game:

Turn 1:

Player 1: Mishra’s Workshop, Mox, Jester’s Cap

Player 2: Land, Ancestral Recall

Turn 2:

Player 1: Land, activate Cap.

Player 2, if they were playing any number of Control decks or Combo decks, just lost the game.

Each turn in Vintage is fraught with myriad opportunities. The top players know what the battles are over. They know that Ancestral is a real threat and to tutor it up, to protect it, and to stop your opponent is a real tactical battle.

Yet there are literally myriads of turn 1 disruption spells that see lots of play in Vintage: Duress, Orim’s Chant, Xantid Swarm, Cabal Therapy, Force of Will, Misdirection, Stifle, and the like. These plays are often designed to force out Ancestral, to protect it, stop opposing Ancestrals and the like.

Consider this line of play:

MDG versus Control Slaver:

Turn 1:

MDG: Land, Mox Emerald, Merchant Scroll for Ancestral Recall

CS: Mox Ruby, Land, Time Walk.

On the Time Walk turn, the Slaver player plays another land and Goblin Welder off the Ruby.

At this point, you have the beginning of a battle. The MDG player really wants Ancestral to resolve, so it will wait until the opportune moment. It won’t play it on turn 2 simply because the CS player has Mana Drain mana up and potential counter backup. More threatening now, Thirst For Knowledge in response to the Ancestral could result in a Mindslaver being discarded. A single activation of the Slaver will destroy the Gifts player.

Turn 2:

MDG: Land, go

Thus, the MDG player shifts back to the control role as it seeks to establish its manabase and prepare itself for the upcoming fight — both over opposing Thirsts and its own Ancestral.

CS: Draw, go.

The CS player does the same. Thus, although Ancestral appeared from the outset to define the game, other threats have immediately come into play to counter the power of Ancestral.

This is how most real Vintage matches look. There is a very strong to and fro — back and forth. Please take a look at some test games I recently enjoyed from my article last week on Meandeck Gifts for some really interesting in game analysis. It takes great skill to consistently and perfectly navigate these land mines.

The fact that the cards are so powerful doesn’t detract from the skill of in game play — it causes us to demand more of ourselves! A single slip-up is generally game over. The cards are so powerful that you will be harshly punished for a flub. That’s the price you pay for playing Vintage — but that’s also the fun of it. The joust — the to and fro – is truly enjoyable. It is tense and it is exciting and that is why Vintage is so popular given the absolutely enormous financial constraints on the format. Sadly, the biggest constraint is still skill. Format knowledge is so crucial that I can’t even imagine how someone could properly conceive of a strategy with limited Vintage experience. You can’t play Stax without knowing which lock components are key and which cards are the best finishers (threat analysis). You can’t pilot combo without an understanding of the obstacles you are going to face (another kind of threat analysis). You can’t judge whether to accelerate or play more control unless you know the risks you face when playing a Control deck.

Empirically, there is no doubt that skill is king. The tournament data very, very clearly bears this out. The trick has been explaining why. I hope I’ve been up to the task.

There is one more component to discuss:

Sideboarding

Sideboarding is what separates the men from the boys. It is where true expertise leads to a kind of inbred, counterintuitive decision-making process that is nothing less than bizarre to the outsider.

Robert Vroman has won two StarCityGames tournaments with his deck, Uba Stax. Like Bobby Fischer, he comes out of seclusion for the first time this year at the Vintage Championship and makes Top 8 with a deck that hasn’t seen Top 8 inside of 2006. He writes up a tournament report, which I encourage you to read in its entirety as it is a fascinating bit of Vintage analysis in its own. But I want to draw attention to a few things that exemplify the skill of sideboarding in Vintage.

Check out what he says in Round 5:

Round 5: Roland Chang, 5C Stax. Win 2-0

Game 1

This whole match was a closely fought Stax battle. I won the roll and had turn 1 Welder. Roland quickly got Welder plus Bazaar, but I had Smokestack and Null Rod, which negated his misplay of Vamping for Trike, Bazaaring it into the yard, and welding generic 4/4 into play. I carefully kept my yard artifact free, and managed to outplay his Welder to keep his Crucible off the table while Smokestack ramped to 3 for several consecutive turns. I wiped his board, and Roland scooped to my remaining Welder.

Board

+3 Viashino Heretic

+3 Tormod’s Crypt

+4 Granite Shard

+2 Duplicant

-4 Tangle Wire

-4 Uba Mask

-1 Trinisphere

-1 Black Lotus

-2 Bazaar of Baghdad

Look at this board plan. Boarding out Lotus? Boarding out Trinisphere? These absolutely bizarre decisions make complete sense and yet, if you hadn’t been playing Uba Stax for years, there is no way you would have thought of it. Vroman is sideboarding out his decks namesake and the ridiculous Black Lotus and Trinisphere for what? Granite Shard? Some crappy Mirrodin uncommon?

That, boys and girls, is why Skill is King in Vintage and why Robert Vorman got 3rd place at the Vintage Championship.

Vroman’s report illustrates two other great points about sideboarding. First, your plans are not simply dictated by the deck you face, but by the skill of your opponent. Note what Vroman says when facing the soon-to-be Vintage Champion:

Talented Gifts player will not attempt a Darksteel Colossus win if they can’t protect it. Thus, there’s no point in trying to pull off the Duplicant defense.

+3 Tormod’s Crypt

+3 Jester’s Cap

-2 Smokestack

-2 Crucible of Worlds

-1 Solemn Simulacrum

-1 Duplicant

Vroman does not bring in more Duplicants, and in fact sideboards the maindeck Duplicant out on the assumption that it will never get a chance to imprint Darksteel Colossus in this match. These are the kind of small decisions that make the difference between winning Vintage tournaments and simply making Top 8.

There is one other point I’d like to illustrate.

Take a look at this note from Vroman’s match against the soon-to-be Vintage Champ:

Game 3

Once I saw Pithing Needles I should have boarded for game 3:

+3 Viashino Heretic

-2 Crucible of Worlds

-1 Uba Mask

Sideboarding is not simply bringing in cards to improve your game against a given deck or answer a threat. High-level sideboarding is far more complicated. For instance, you may anticipate, as a Stax player, that your Gifts opponent will be bringing in Pithing Needles. These needles can stop your Bazaar and your Welder. You would never need artifact destruction for Gifts normally, as the only threatening artifact is indestructible. Yet, Robert Vroman may be inclined to sideboard in Viashino Heretic. Not exactly an exciting card and certainly in the board for other matchups. Yet he brought it in anyway because it served a critical function. Vroman didn’t sideboard during game 3, but he cites this as something he should have done. Many other Stax players, such as Kevin Cron, are well known for this kind of odd sideboarding strategy.

Closing Thoughts

Vintage tests skills, to be sure. They are very different skills from other formats. Other formats are much more so defined by creatures. The battle in Vintage is over key spells. It is a resource war defined by card advantage, tempo, and acceleration. Creatures service the battle. True Believer tops Gifts and Tendrils. Kataki is also artifact hate. Jotun Grunt stops Welders, Ichorids, Worldgorger Dragons, and even Yawgmoth’s Will. Goblin Welder and Worldgorger Dragon are combo parts with legs. Same with Xantid Swarm and Elvish Spirit Guide. Vintage is a war of resources, to be sure. But it can be an intense battle that begins from turn 1 and doesn’t end until the game is finished. Each “bomb” is often answered with a tactical counterthreat. You play Ancestral, I drop Null Rod; you try to bounce it, I drop Smokestack. Or, you play Ancestral, I play Windfall, negating your Ancestral. The advantage of Ancestral is often nullified by the next play. Each turn in Vintage poses threats and risks that most decks spew forth.

Vintage is as different from Standard as Standard is from Limited. Each format tests very different skills. The power level of Vintage doesn’t make it less skillful. It makes it more intense. It tests format knowledge, metagame insight, optimal design, optimal sideboarding, and the tough choice of when to mulligan. Perhaps more so than other formats, Vintage is a puzzle format.

Here is a puzzle from my primer on Meandeck Tendrils:

This hand, undisrupted, wins the game on turn 1 over 50% of the time! Yet, getting there is the trick. How can you make the decisions in a reasonable amount of time? When you are compressing a full game of Magic into one turn — and you can’t even make the first decision until you can properly evaluate where you need to be?

Consider my game 1 Gifts from my last article… How can you know what to optimally Gifts for with so little information? Certainly, you can make some good or even great Gifts piles — but perfect? Each tutor presents options. When you open a hand with two tutors your options grow exponentially — you have to consider the impact of each tutor upon the other.

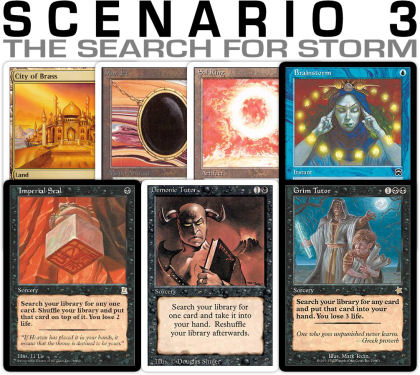

Consider this opening hand from a Grim Long article I wrote in the Spring:

I still have no idea how to crack that hand, even from an objective viewpoint.

Vintage is defined by many things, but today, more than ever, it is defined by pilot skill. And as frustrating as it is to make mistakes, I wouldn’t have it any other way.