Everyone can look at a decklist and read cards. They can look up what cards do and maybe figure out if the deck is something they would be interested in playing or how it works on a surface level. But not everyone knows how to delve into a decklist and truly understand what is going on with the deck and how to play or beat it.

There are several reasons you might be looking at a decklist. If you are looking for a new deck to play, being able to understand a deck just from reading the list can help you evaluate if it would be a good deck for you. Once you have chosen a deck, you will want to make sure you have an understanding of the metagame, so reading decklists and thinking through your matchups against them can be very helpful when preparing for an event.

In the Top 8 of high-level tournaments, such as the Pro Tour or this past weekend’s SCG Invitational, each player has the decklists of the other players. This lets them prepare and plan against a specific list instead of just an archetype. You are not given a lot of time with the list, so being able to understand it deeply in a short amount of time can give you a strong edge in difficult and high-pressure play situations.

Lands

The first thing I look at when starting to evaluate a decklist is the manabase. There are a lot of hidden secrets that can be found from this starting point. The number of lands you see in a deck can be a big indicator of whether this deck wants to go to the long-game or not. If it is only running twenty lands, it will probably be much more aggressive than a deck that is running 26, hoping to hit a land drop each turn.

Which lands were chosen can be helpful to deduce information about the decklist as well. If there are several lands that enter the battlefield tapped, it is more likely a deck looking to move into the late-game that does not mind being a turn behind sometimes. If a deck is running mostly fastlands, then they probably are not ever looking for their fourth land drop and are probably quite aggressive.

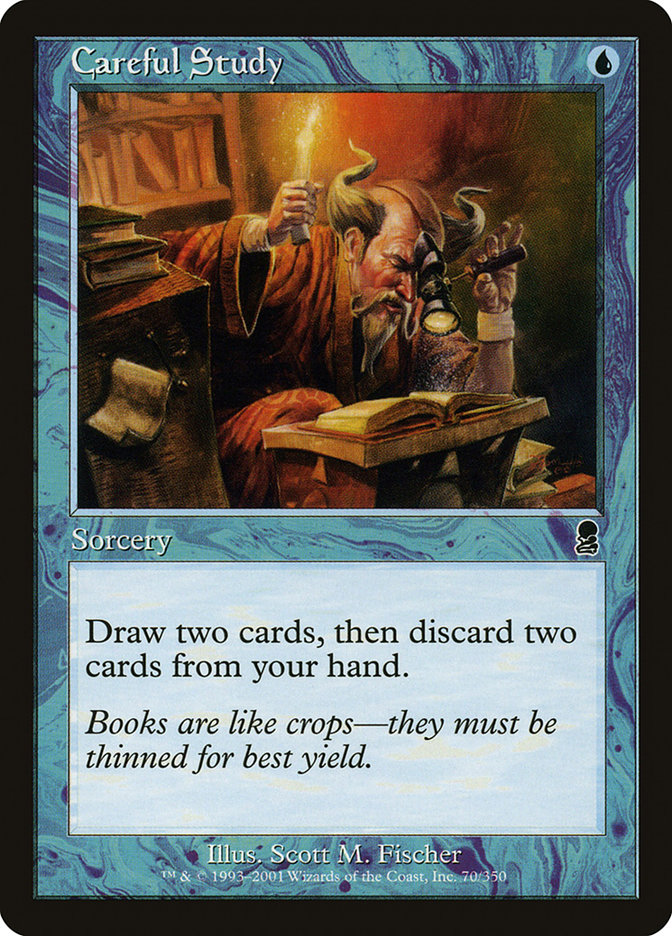

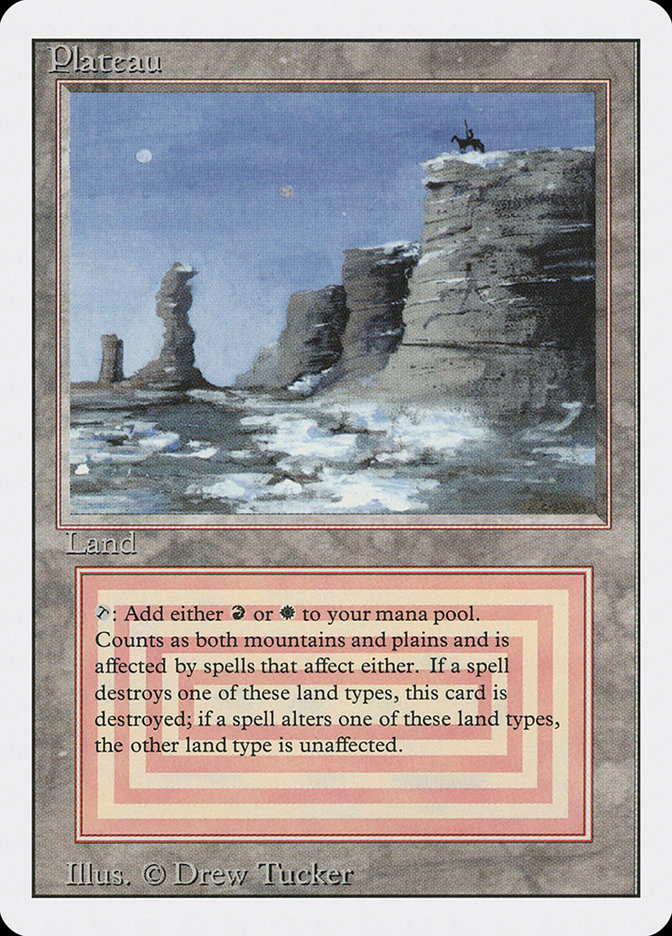

How many lands does each deck want if they’re playing these cards? Why?

The manabase will tell you which colors a deck is in, which in turn can give you an idea for the fundamental strategy of the deck. Watch for greedy manabases of three or more colors. This often leads to high power and flexibility, but also tends to make such a deck less consistent and more likely to die to its own mana problems. The likelihood of getting every color in the right proportions goes down with more colors, which leads to a deck more prone to being punished.

Consistency

Generally, whatever isn’t a four-of can indicate the weak spots of the deck or parts of it that don’t fit in with the most obvious linear plan. Pay attention to these clues and you will be able to find not only their big bombs against you but also what decks they may be trying not to lose to. If you see a deck with maindeck graveyard hate, they are likely not well-positioned against a deck like Dredge without it. If they are very worried about a certain matchup, then they are more likely to run hate cards in the maindeck.

Sometimes you can get away with running more than four copies of a card if there are multiple cards with the same effect. For example, Elves gets to run four Llanowar Elves and four Elvish Mystic, which are virtual reprints of each other. Similarly, Burn runs more than twenty spells that cost either one or two mana that will do three damage to target player; it doesn’t really matter which burn spells you draw as long as you draw enough of them.

This redundancy will increase the consistency of the deck, even if you don’t always see exactly the same cards. Homogenizing “like” cards is a great way to consolidate your understanding of someone else’s deck.

Conversely, any cards that are a one-of can give you a clue to the deck as well. If the opponent is running a lot of different singleton cards, check to see if there is a way to consistently find the one that would be best in any situation. Cards like Chord of Calling and Collected Company make it easier to run fewer copies and still see them consistently.

A single-copy card can be a big bomb, a specific answer, or even a combo piece that is easy to get. You can also check for any strange outliers in the deck, like a card that is not in the deck’s colors. There must be some way to play it or there must be some value to having it in the deck, so you can try to identify what that card is useful for. The same can be true for unusually high-costed spells that a deck may be trying to cheat onto the battlefield, like Emrakul, the Aeons Torn in conjunction with Nahiri, the Harbinger.

Some decks are split into two “halves,” such as ramp decks. These tend to be less consistent but much more powerful ahead of curve. There is the danger of drawing all threats early or all ramp spells late, making it difficult to complete the ramp gameplan.

Having a large variety of cards gives more flexibility and less consistency to a deck. Both types of decks are great, but it helps to know how consistent the decklist you are evaluating is.

Fair or Unfair?

Next I want to know if the deck is fair or unfair. Fairness is a way of evaluating the play style of the deck. In Standard most decks are fair, making it easier to identify the ones that aren’t. In other formats it is less clear, so taking the time to determine the fairness of a deck can greatly help your understanding.

A good question to ask oneself when determining if a deck is fair is, “Does it win by attacking with creatures over two or more turns?” If so, then it is generally considered a fair deck. If not, then you will want to figure out what its win condition is. From there you can work backwards and figure out how it wants to cast its win condition, and then how that situation needs to be set up. Taking away that favorable situation gives you a higher likelihood to win.

Fair Win Conditions

Once you have determined that you are looking at a fair deck, you will want to figure out what turns it is trying to attack on. Look at the creatures in the deck. Are they primarily small cheap threats? If so, the opponent will likely be trying to start attacking on turn 2 or 3. What about larger and more midrange threats?

How much time do you have to live, given each of these threats?

Once you know the turns where it begins to be the beat own, you can figure out its plan to get to that point. If it is playing large threats late, then there must be some control element to survive in the early-game. Perhaps it is set up to ramp to those large creatures early, like Titanshift, or perhaps it will play a Pack Rat every turn and overwhelm the battlefield. It’s hugely important to consider how the deck will recover if it is stalled or interrupted by the opponent.

Unfair Win Conditions

When you are evaluating an unfair deck, you have to look around to find the win condition. These are often combo or control decks with large finishers that will close out a game in one attack.

How often can a game be won if this creature activates once?

First, note any obvious outliers, such as high-cost spells or one-ofs that can be tutored for. This indicates a combo. Filter cards can be as effective as tutors in decks like Jeskai Control to find the pieces (Nahiri, the Harbinger to ultimate for Emrakul, the Aeons Torn) it is using to finish the game. Once you have found the win condition, you need to figure out how it works and how it can be stopped.

Sideboards

The final thing I do when evaluating a deck is consider its position in the metagame. A strong clue to its strong and weak matchups can be found in the sideboard. For example, if you look at a common sideboard for Merfolk, you will see Hurkyl’s Recall and Gut Shot. You may have already deduced that artifacts would be an issue, since the deck is mono-blue, but now you know for sure that Affinity is a very hard matchup for the deck. If you see lots of counterspells in a sideboard, then combo is probably a bad matchup for that deck.

You can also determine if the gameplan changes after sideboarding. Some decks use a transformative sideboard. Pyromancer Ascension sometimes plays very few creatures in the maindeck aside from Thing in the Ice, but it can transform into a Young Pyromancer and Monastery Mentor deck in Game 2. Transformative sideboards are meant to “getcha” in Game 1 with spells when you’ve got removal and “getcha” in Game 2 with creatures when you’ve sideboarded out your removal.

Conclusion

Delving into a decklist quickly and learning to understand decks beyond just cards on a page can help you to become a better player. Understanding what a deck is looking to accomplish with only a short amount of time to figure it out can be a challenging skill to master, but with practice, anyone can do it. Try grabbing a decklist you don’t know very well and analyzing it along with this article. Hopefully you can gain a new insight into that deck.

Have a wonderful week, and as always, happy gaming!