Cards, “Facts,” Mentors, Multipliers, and Using Every Part of the Buffalo: Five Useful Ways to Get Out of Your Comfort Zone

Part One: Cards

(or, the “filthy” Finkel seal of approval)

A week or two ago, there was a small event in the City of Brotherly Love that you may have heard of, Pro Tour Philadelphia 2011. There were some players who made Top 8. There were some other players who made Top 16. This story involves three of them.

“After hours” there was a side draft. On one side was FinkelDraft regular Eric Berger and two Top 16 finishers, FinkelDraft alum Tom Martell and FinkelDraft namesake Jon Finkel. On the other side were two players who made Top 8 (but Tom didn’t tell me which ones).

Tom has been playing brilliant Limited Magic this year, including six rounds in Philadelphia that he says were his best play, maybe ever. His ability translated to the afterhours tables, against one of those Top 8 competitors.

The game had slowed to a relative standstill.

Tom (U/W) already had some Roc Eggs in play and some other do-nothings.

His opponent—fresh off the Top 8—had been leaving up mana every turn since the second turn and had had at least two cards in hand the entire game. Martell correctly read him for a Mana Leak.

Tom got to seven mana and elected to hold his eighth land for some turns in order to reinforce his opponent’s notion of being able to hit something with the Leak. Eventually Tom played another Roc Egg and said, “You are really never going to get any action out of that Mana Leak.”

Read and leveled both, his opponent quietly seethed.

Tom drew a nice one, then played the nth Roc Egg (again leaving open Mana Leak mana), but followed up this time with a sandbagged Benalish Veteran.

The opponent snap-slammed Mana Leak, proclaiming, “I guess you will get Mana Leaked after all!”

Martell smiled and flashed the card he had just drawn: a Pentavus.

“Filthy. Just filthy,” admired his on-looking teammate Finkel.

And I think we can all agree that it was.

There is quite a bit going on in this story, but we are only going to focus on two things. Tom correctly read his opponent for Mana Leak and saw that he valued the ability to play Mana Leak to the exclusion of making proactive plays. I am sure you have been in similar spots in both Constructed and Limited Magic, often to the detriment of your success.

He knew he could goad the dragon and waltz him into a spot where he would take any opportunity to use the now seemingly devalued Mana Leak. This was an admirable exercise in certainty and mind control… But it was fed by two broader concepts 1) people in general are incredibly invested in things that they have (even when those things aren’t doing them any good), and 2) perhaps as a subset of the previous, competitive Magic players in particular overvalue cards.

There are lots and lots of examples of the first. I am sure you can think of some from your own everyday life. This can manifest in everything from an unwillingness to invest (“that’s my money!”) to how difficult it can be to change someone’s mind, even in the face of superior facts and logic (“I was raised to…” or “this is the way we have always done it”). Most competitive Magic players learned card advantage as the first big concept, so they strangle the concept of “cards” (and their own likelihood to win) over and over, even when it will lead to inevitable failure. Consider as an example the unwillingness of many players to mulligan speculative hands that are not generally likely to win (you have both lands and spells, but your hand “doesn’t do anything” or you can’t actually play your spells with the lands you have, like a Ramp deck with a six, three lands, but no way to accelerate).

How did Tom exploit these?

- He challenged the opponent’s model of the universe: Ha ha you have been doing something foolish these seven turns.

- He took something away—something his opponent obviously valued—while baiting him emotionally: You think you have a Mana Leak, but it is actually worthless. [Think of this like a clueless speculator desperately holding onto a bad investment.]

- Then he gave him hope: Here’s a Glory Seeker. You have a chance to get out of your bad investment at a break even! (Mana Leak, cards-wise, is a one-for-one.)

- His opponent did everything he wanted: Up to, and including losing.

Keep in mind his opponent at B/U probably had a historically driven long-run advantage over Tom’s U/W deck. B/U has traditionally had more removal, more relevant evasion, and so on. Tom might have had the ground locked up, but it’s not like he was going to win with a battalion of 0/3 bricks. By giving his opponent the clear opportunity to recoup on a seemingly bad investment, playing on his presumed devotion to card economy, Tom was successful.

What does success look like? Anyone who has ever decked himself in Limited (I have!) with his own first picks knows that as good as card advantage can be, the winner isn’t the guy (necessarily) who draws the most cards, but the one who kills his opponent.

So two things from Part One: As I have written a couple of times this year around the concept of scarcity in particular, I would challenge you to revise your prioritization of card economy relative to other elements of the game. All other things held equal, card advantage does in fact increase your options (good under the Finkel paradigm). On balance, real-life games that can actually go either way rarely fit nicely into simple boxes.

Secondly, I would encourage you to let go of whatever limiting belief set you have in order to get out of your comfort zone, and improve.

Part Two: “Facts”

So let’s start with a (potentially) super controversial area, something that might be super duper difficult to let go of… Your devotion to what you think are facts.

Personally, I have, for the majority of my life, been a strong devotee of “facts and logic.”

I have recently switched alliances from a “fact”-based paradigm to one that is based on usefulness. That is, rather than “is this factually true?” I try to ask “is this useful?”

Keep in mind, generally speaking, things that are not true are generally not useful. My issue is that when we talk about Magic, it is incredibly difficult to “prove” something is “true.”

Something that is seemingly irrefutably true… can be not-true?

Huh?

Here is an example. I once had a playtest session where I was running a B/W midrange creature deck against Brian David-Marshall playing a rogue U/R deck with goofball 2/2 creatures like Izzet Chronarch and Izzet Guildmage, plus some oblique, seldom-summoned sorceries. “It is pointless to continue testing this matchup,” I declared. We had not finished the typical ten-game set that we ran under in those days. BDM—typically even-keeled—was becoming increasingly incensed as I (like Tom in the previous section) was baiting him.

An on-looking Jon asked if he could tag in for BDM with the same deck.

It was like Bobby Fischer’s World Championship chess run, forcing the concession with tons of games left as-yet unplayed. Despite the six or eight games in a row that I beat BDM (kill your guy, hassle you a bit, get in), Jon suffocated me with an incredible level of restraint and patience. All he did was hit his land drops. Then, he wouldn’t use his creatures until he was getting massive two-for-one value from them, so he minimized my creature removal. My B/W deck wasn’t that fast, so I wasn’t racing. All in all…

I.

Could.

Not.

Win.

Was it “true” that my B/W deck beat BDM’s U/R deck? During hour number one, I would have proclaimed this as a statement of fact.

Or is it simply that Jon Finkel is so much better than I am that he can re-write our common notion of facts and re-shape the LEGO bricks that we use to build our universes?

In all our thoughts and experiences, we utilize a combination of images and the order and priority with which we organize those images… That is how we structure… everything.

I remember in 2000 Adrian Sullivan calling me about “my Black deck” and his claiming that his StOmPy deck beat it consistently. I mean this was a ludicrous statement from my perspective (and this was pre-US Nationals, but to anyone who knows how Hernandez v. Finkel went), but Adrian isn’t stupid, and he wouldn’t have bothered to make the call if he weren’t seeing these results.

What I did was ask him how he was playing the black side and suggested that he do some things differently. How aggressively was he using Perish? How much was he trying to grab up an explosive chunk of card advantage rather than just managing battlefield and life total with Vicious Hunger? What about Vampiric Tutor and Yawgmoth’s Will? Did he use Dust Bowl pre-Yawgmoth’s Will and then re-use Vampiric Tutor to chain Will after Will?

Adrian called me about two hours later, saying “Never mind.”

Why did Jon crush me using the same set of tools that BDM had (but was unsuccessful with)? Why did Adrian about-face so starkly?

Because in these cases, the frameworks were not about the “facts” or pictures or materiel in front of anyone, but how they were assembled.

If I give you the following “decklist,” what do you end up with?

- baking soda

- butter

- peanuts

- sugar

- vegetable oil

- wheat flour

- water

- yeast

This:

Or this:

?

How about an even simpler question…

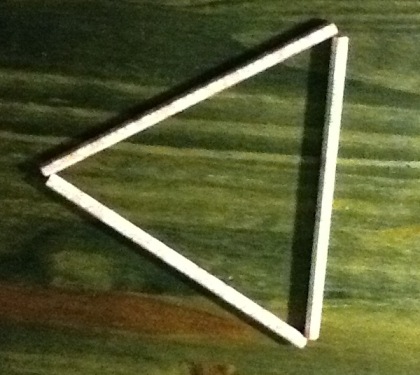

If I give you three of these Hello Kitty pencils and ask you to link them up together, end-to-end…

… What does it look like?

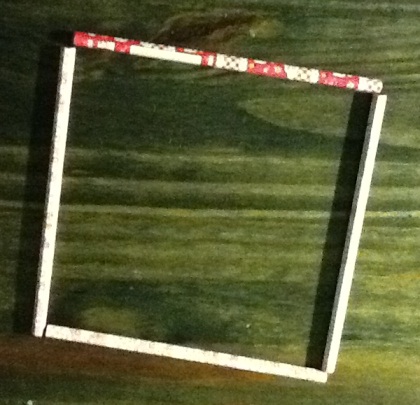

How about four?

…

Given the above equilateral triangle and square, if I asked you to connect five such bits and sticks, you would probably predict this:

…

Now

…

I

…

am

…

buying

…

space.

But why not this?

Just as you can end up with either a peanut butter sandwich or a peanut butter cookie—quite different foodstuffs—using much the same ingredients, the same five line segments can be combined into either a pentagon or a star (or maybe other things I haven’t thought about yet).

When you think about how such a simple set of ingredients can yield such different pictures, you have to start questioning some of the things you might have once held so close. How much more complicated a picture can we paint—however reductively some writer has described to us—with a sixty-card deck list? Seventy-five?

A year or two ago, I made a deck called Grixis Burn (Cruel Ultimatum and Sorin Markov in the world before Jace, the Mind Sculptor), and that was successful for some people. I mostly just put it up on my blog (http://fivewithflores.com), as I wasn’t doing any deck technology for any particular site at the time, but it did well on MTGO, and players up to and including a Gerry Thompson became interested and adopted it for a time.

One of the things I liked about the deck was my sideboard, which included Vampire Nighthawk. A few moons later, I won a Nationals Qualifier with a different Grixis deck and bought a key draw with Vampire Nighthawk out of my sideboard against RDW.

In between the two decks, Gerry told me he hated Vampire Nighthawk.

Was Vampire Nighthawk “good?”

If it is good, could I prove it? Can it be thought to be factually good or not good?

I certainly re-thought my position because the commentary came from Gerry.

Was I “wrong?”

Really, the question should be whether either my original innovation or Gerry’s opinion were useful, or contextually so. I know I was happy to have had Nighthawk in the tournament I qualified, regardless of Gerry’s opinion.

Last week, Chris Lansdell from the Horde of Notions podcast asked me about U/G Infect for his FNM. If you looked at the greater scope of Standard—MTGO results, LCQ results and so on—you would see successful Red Decks… Not the environment where U/G is likely to be successful. If you ask a top Pro writer or whatever, you are likely to get a comment like “too much Red… U/G isn’t good now (if it ever was).”

However Chris told me that his FNM is mostly Caw-Blade, Valakut, and B/U Control—all superb matchups for U/G Infect… close to un-lose-able in extreme cases. So I told him how I would approach that kind of a room.

Is U/G “bad?”

Is there “too much Red?”

Can we answer either of these questions factually?

If someone told him that U/G was bad and / or there is too much Red, would that person be “lying” to Chris?

Lansdell ended up going 3-1 in FNM, losing only to B/U in the same way that I did in the TCGPlayer 75k… Sure to win with Livewire Lash in play, but bereft of a beater for DI turns.

Takeaway: The paradigm that most of us are raised with… One that is obsessed with “facts” either isn’t useful at all [can we prove that?] or at least a boatload less useful or applicable than many of us start off believing. If you switch how you think about analysis, data, and opinion coming in, and ask yourself is this useful to me as your baseline instead, my guess is that you will get better results.

Or at least I have.

Part Three: Mentors

How do you temper the above?

One way is to consider the source of the information that you have coming in.

I have been lucky in both my Magical and professional lives in that I have had the opportunity, over and over, to acquire amazing mentors.

What did I say about the Vampire Nighthawk thing, above? I considered changing my position only because the commentary came from GerryT. If it had come from a less successful designer, I would have probably ignored it. I ended up ignoring it anyway, but I wouldn’t even have thought about it.

Osyp Lebedowicz said something interesting about Billy “Huey” Jensen in an interview about the Hall of Fame this year. It looked to me like Huey was going to get in for a minute, and I was proud to have been near the point of the spearhead on that run. What Osyp said was that if Finkel and so on come out and say someone should be in the Hall of Fame, it doesn’t matter what the bulk of the rest of the committee thinks. Huey has, unambiguously, the only pedigree a prospective Hall of Famer should need.

I think about it like this: If all the best players (let’s say Pro Tour Champions) from a particular country (let’s say the USA) feel one way about the skills of a particular deck designer… Shouldn’t you balance that opinion in a particular way when considering that person’s ability as a deck designer relative to say, some forum troll or “your buddy” from your local store?

Just a thought.

This is my operating guideline; use it if you think it’s useful, or reject it and only use some of the other stuff in this article (if you think they are useful, of course): Everyone has an opinion. Often they have opinions about areas where they have never experienced success. Especially if someone is better than I am at something, I think about what they have to say, but especially where they disagree with me, I never consider the opinion of someone who has not experienced success in that area.

Remember—It’s important to know what success looks like!

Part Four: Multipliers

In business there is a minority (but seemingly, to me, increasingly true) concept that you can reduce an operation to an equation… Number of customers times response rate times average lifetime value times retention rate, mitigated for risk, yadda yadda yadda. Companies that are good in only one or two areas often end up over-specializing in those… And while they can be successful (the thinking that “all other things held equal, if you bring in twice as many bodies, your revenues will double”), there is a much wider world than those one or two things.

Increasingly, we can see that more complicated, more complex, higher-risk “equations” can give especially smart people with the resources to execute on them greater rewards than a mere “doubling” or so.

How does the multiplier concept apply to Magic?

A year or two ago Gabe Carleton-Barnes and I were laughing about my decision to cut off green. I ran stats showing how much less successful I had been when playing green than not playing green… and amazingly, at the time, I played green about 75% of the time!

Is it “wrong” to play green? Certainly not 100% of the time. But was it useful to limit myself this way? My performance—including my Nats Qualification with Grixis and recent Exarch Twin win—both benefitted from that decision.

Anyway, what Gabe pointed out was that Jon and Kai “just figured out blue first.”

It wasn’t just that they figured out blue. Jon’s first Pro Tour Top 8 was a deck with Tithe; to this day he prides himself on that four-color mana base whose only blue card was Counterspell. Kai became Kai during the Combo Winter using a deck chock full of library manipulation—Brainstorm, Impulses, Intuitions, Merchant Scrolls—and won his PT Donate with more of the same.

And just the last Pro Tour… One of the fastest PT formats in memory, and Jon Finkel finished less than a win out of Top 8. With what? Ponder, Preordain, Gitaxian Probe, and so on… A tremendous number of touches to his deck, giving him more opportunities, action after action, to access that part of him that is so much more celebrated than every other player’s ever—the ability to weigh options and make decisions.

Let’s bring it back to mentors.

What do the very best players choose to do?

I have been preaching this for a few years (and I even wrote an essay back in 2005 talking about English children jumping into concrete platforms at King’s Cross, trying to get to Hogwarts). Don’t do what the experts say to do (necessarily). Figure out what the very best actually do, and do that.

There was a sentiment a few years back that decks full of Tutors gave bad players more and more chances to screw up. But as you improve—or move to improve—your game, how do you approach your very best potential?

Part Five: Using Every Part of the Buffalo

What is more actionable than almost any other suggestion I can give you in this article is to know everything your deck can do, so that you can eke out every win (especially when your opponents don’t know those capabilities).

I have rarely been so impressed as when I was watching Patrick Chapin qualify for the TCGPlayer Championship with his 4-0 sweep of the last grinder. Patrick would pull out games where he looked like he was losing, typically by setting up the Diamond Cutter in the form of Hero of Oxid Ridge, and winning by exact damage via battle cry, taking advantage of the opponent’s inability to block.

I would never see the play coming (nor, do I think, did Patrick’s opponents), then suddenly it was kick, wham, Diamond Cutter; and the masked man from Mexico would be pulling off his luchador hood, and underneath? The Innovator!

This is a clear echo to Patrick’s oft-referenced lament that players of the MTGO generation—hive mindedly plucking decklists off of the Internet—that, even when they are moderately successful, so often lack the understanding of just what technologies lurk within the decks they are slipping on like hermit crabs.

It is also a great example of the possibilities—even core-strategic possibilities—that exist for some players with particular multiplier access (i.e. a Patrick) versus everyone else. How many wins did he get, in that grinder, at the Grand Prix, where a player simply copying his deck would never have seen the path? How many opponents never saw death by Hero coming and would have made a different attack?

I am sure that most players—like myself, in fact—looked at Patrick’s RUG deck the first time and puzzled why he might not have an Exarch Twin combo. Then, they would look up odd choices like Tuktuk Scrapper or assume that singletons like Hero of Oxid Ridge were there as bullet value (like, you know, Tuktuk Scrapper). In fact, and watching Patrick tank, it was almost like Dallas Paige in process… Sure, he won on value two-for-ones more often than not, but it seemed like Patrick was always looking for a way to insta-kill the opponent by finding a spot to stick the Hero of Oxid Ridge.

And my guess is, that many players (uninitiated) either cut the Hero pre-tournament, or it is the first card they sideboard out.

On balance, you have the man himself, with his RUG-Pod Weapon of Choice sculpting play with Phantasmal Image and Phyrexian Metamorph with absolute precision. What I found most impressive was how he would use his knowledge of “Clone” rules to manipulate mana costs.

Case in point, any time he could play the two- or four-cost Clones to copy a three… with the ultimate goal of transforming it into a Hero, often killing the opponent on the spot, from a position where a lethal Alpha Strike was often very difficult to predict.

Don’t assume that just because you have five Hello Kitty pencils sitting in front of you, they are meant to Voltron into a pentagon, while complaining at the top of your lungs that what you really needed to win was the five-pointed doom blade of a star (or maybe even a square, triangle, or, you know… just a Hello Kitty pencil).

LOVE

MIKE