A few weeks ago, I wrote an article about breakpoints. Think of that article as an introduction to the art of using the cards your opponent has played to deduce which cards they haven’t yet. More specifically, the concept of breakpoints is a method of determining a point in time at which your opponent did not have access to a certain card or type of card. The idea is that by working forward from a point where we know they didn’t have the card we’re worried about, we can develop a much more accurate estimation of how likely they are to have it now.

Sounds simple enough, and sometimes it is. But you have to understand that when it comes to reading your opponent, change is the enemy. Game states that change little from turn to turn are easy to parse. If only one or two cards are flowing from library to hand to battlefield every turn, understanding how likely your opponent is to have found a specific card is not very difficult. But often in Magic, cards flow more freely than that and our task becomes much harder.

Buckle up, dear readers. It’s time to talk about fluid dynamics.

Have you ever heard of Dominion? What about Star Realmsor Ascension? If you haven’t, don’t worry; this tangent won’t last very long. All of these games are in the hobby gaming genre called deckbuilding, so named because the key feature of these games is building your deck as you play. You do so in full view of the other players, giving them perfect information as to the contents of your deck. You might think having access to such a wealth of information would make reading your opponent very powerful and important in deckbuilding games, but you would be wrong.

The reason you’re wrong is that deckbuilding games are on the far other side of the card flow spectrum from Magic. In these games, you discard your whole hand at the end of every turn and draw five new cards. Every turn is a breakpoint, a complete reset on the contents of their hand. There’s no point in trying to figure out what’s in their hand, because by the time you have enough information to do so, they will have a whole new hand.

Of course, Magic never even approaches deckbuilding levels of card flow. Thankfully, as I happen to very much enjoy reading my opponents and would like the game less if doing so was less feasible. But despite being a far cry away from any scenario we are likely to encounter in our Magic careers, thinking about deckbuilding games can help us understand the relationship between card flow and reads. In fact, here you go, the first law of card flow dynamics:

The more cards they see, the less you know.

Simple and eloquent, no doubt destined for textbooks everywhere someday.

The base rate of card flow in Magic is one card a turn. This is what we have grown accustomed to as Magic players, and is important to keep in mind. As little children, many of us were given color-by-number pages so we could make beautiful drawings without much skill. Well, forget all that, because Magic-by-numbers is much more difficult for most of us than Magic-by-feel. Computing endless lists of numbers and percentages in-game is challenging, time-consuming, and ultimately not very useful. Instead, the way we need to think about different card flow scenarios is by comparing them with the base one card a turn rate that countless games of Magic played have helped us to internalize.

One-Off Card Draw

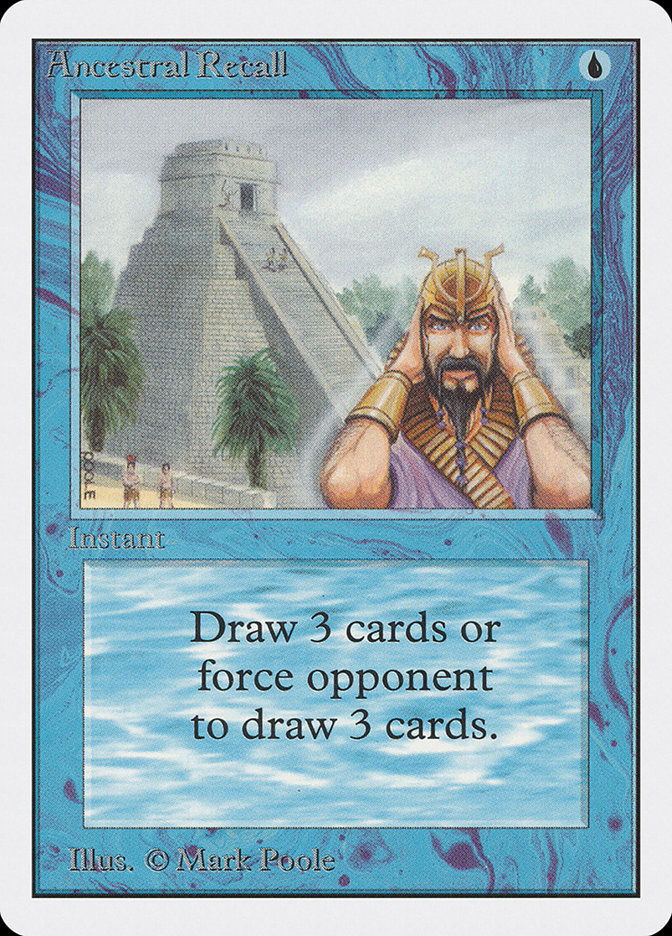

So, let’s begin. The simplest modification to the base card flow in a game of Magic is your opponent finding a way to draw extra cards. Magic is chock-full of cards that allow this to happen: Ancestral Vision, Cryptic Command, Sphinx’s Revelation, and Painful Truths, to name a few. Whenever a card like this resolves, the job of figuring out what cards our opponent has gets harder. The effect is exponential, with an additional three cards being much harder than an additional two, and an additional four being still much harder than that.

The first layer of attack we own to process quick changes to our opponent’s hand like these is to treat every extra card they draw as another turn that has passed. If we come to a turn where we determine that they do not have a sweeper effect, and then on the next turn they spend their turn drawing three cards, we want to treat this situation as if an extra three turns have passed since we knew they didn’t have a sweeper. All right, that’s reasonable and simple enough, but can we do better?

Well, since I asked the question, you probably guessed that we can do better. Good guess. First, let’s look at what card draw is in Magic terms. Spells that let you draw cards exchange tempo for an advantage in card quantity. After spending mana to draw cards, it is imperative to use those cards to recoup the tempo drawing them cost. As such, large one-off card draw effects incentivize their wielder to sequence their spells in a way that prioritizes mana efficiency more than they normally would if they came by the same cards at a steadier pace. We can use this tendency to better deduce the cards they have.

Imagine you are playing a match of Modern Jund against U/W Control. You have developed a reasonable battlefield state of a couple of Tarmogoyfs and a Dark Confidant against just seven lands, but at the end of your turn they cast a Sphinx’s Revelation for four. Uh-oh.

The game is drastically changed, and the key to understanding what their new hand looks like is watching how they utilize their mana. It’s very likely that they will have found a way to deal with the battlefield state you are presenting, but we can learn a lot by watching how much mana they waste while doing so. Essentially, the more mana they waste on their next turn, the weaker I am likely to believe their hand is. If they draw, play a land, cast and plus a Gideon Jura, and then cast nothing and leave three mana unused when I swing lethal at him, I will play the rest of this game as aggressively as possible, attempting to end the game before they claw their way out of the hole they are in.

Another important thing to keep in mind is that drawing a bunch of cards at once disguises the number of lands in hand. We are used to players playing a land every turn if they have one, and we generally have a reasonably good idea of how many cards in their hand are likely to be lands. But when someone draws an extra three cards at once, our intuitive understanding of how many lands they have gets thrown all out of whack. Because they can only play one land every turn regardless of how many they draw, drawing several cards in one turn can result in lands getting stuck in their hand. In general, until proven otherwise, you should assume that slightly less than half the cards they draw are lands and use that number to calculate their effective hand size of spells. Of course, the more cards they draw, the more accurate this estimation becomes.

Scry

Magic has been around a long time now, and our card draw effects get a lot more complicated than simply adding the top card of our library to our hand. Now that the scry keyword is an evergreen mechanic, we can expect to see it often going forward. It behooves us to have a good understanding of the information we can glean when our opponent scrys.

When thinking about what kind of card our opponent is likely to leave on top with a scry effect, we need to have a solid grounding in the idea of risk aversion. Basically, people tend to do what they can to mitigate risk when confronted with the unknown. In Magic scrying, this translates to players being likely to leave cards on top when they are decent, but not great. Rather than risk drawing something worse, players will tend to make the best of anything borderline workable.

So how can we make use of this idea? Often, it means that when something does get pushed to the bottom, there is a clear and identifiable problem with our opponent’s hand. Most commonly, they are dealing with mana issues of some sort and either want or do not want lands, but could also be flooded on removal and need a threat or vice versa.

Whenever an opponent of mine scrys a card to the bottom, I start trying to figure out what resource they are lacking or have too much of. This comes up often in Magicthese days, ever since the advent of the new mulligan rule. Before any cards have been played, this idea of scrying away only to fix a very obvious problem holds almost all of the time. Sometimes the problem will be quickly identified when they miss their third land drop, and other times you will be able to figure out that they are holding a plethora of removal using this information.

Looting and Rummaging

It takes cards to make cards, at least when dealing with looting and rummaging. These mechanics are the most interactive forms of commonly seen card flow, as they provide us with a ton of information on the cards our opponent is staring at in the form of the card or cards they chose to ditch. Obtaining valid and valuable information from their choice of discard can win you games.

Let’s start with a fun one: the case where they just discarded the card you are most afraid of. Spoiler: they have another. Some of the most dead-sure reads I’ve had in my life involve playing around a second copy of a card they just discarded. In Standard last season, I used to hold onto my second copy of Archangel Avacyn rather than pitch her to Nahiri, the Harbinger to avoid giving away that my opponent could expect to have to deal with an indestructible Angel on their next attack step. Never assume your opponent is just making a colossal mistake and pitching their only copy of their best card. Give them the benefit of the doubt; if they are making a mistake, you will likely win anyway.

Okay, but what about the times when things aren’t quite so clear-cut? Often, you can use the cards they discard to get insight into where they are trying to guide the game. If they discard card advantage spells, they either think they are too far behind to afford them right now or are trying to end the game quickly themselves. If I see my Grixis Delver opponent discard a Cryptic Command to their Desolate Lighthouse, I am going to try very hard to hold onto any copies of Terminate I may have, because I foresee some Gurmag Anglers in my future. Clearly, they do not see this game going very long.

Of course, we can also use their choice of discards to identify potential problems with their hand. If they are discarding lands every time they loot, they could very easily be somewhat flooded. If they discard powerful but expensive cards early, they probably have additional threats but haven’t yet guaranteed that they will ever be able to cast them. Identifying the holes in our opponent’s draws can go a long way towards guaranteeing the path we select to take the game down is one that matches up well for our draw and poorly for theirs.

Desperation

Thus far, this discussion of how card flow affects reads has assumed a relatively even game state. But game states that look even aren’t always so, and the amount of resources our opponent devotes to card flow mechanics can often clue us in that we may be further ahead than we thought. Most of us Magic players have had the game experience where we are presenting on-battlefield lethal if we can just untap, but first we must sit there in agony as our opponent casts card draw spell after card draw spell, searching for an answer. All we want in these moments is for our opponent to sigh, reach their hand across the table and shake our hand, acknowledging that they were unable to find the answer they needed.

But things don’t need to be so cut-and-dried for our opponent to become desperate. Pay attention to the amount of mana they spend on card flow, as it’s often the first sign that they are sailing through murky waters. When they start to spend an inappropriate amount of mana on card flow for the stage of the game you are in, something’s up. When your Grixis Control opponent spends their turn 3 casting two Serum Visions and a Thought Scour instead of dealing with your Wild Nacatl or presenting a threat of their own, you are further ahead than you may have believed.

The specialized types of card flow also have their own unique ways of showing desperation. Repeated scrys to the bottom are always a good sign; very little in Magic is as encouraging as watching a Glimmer of Genius or a Serum Visions scry both cards to the bottom. When you see your control opponent loot away an Ancestral Vision against your Jund deck, you know they are trying to figure out how they will not just be dead four turns from now.

Learning to read into what cards your opponent has in hand is both one of the most difficult and rewarding parts of Magic. Doing it well will win you games, but unavoidable mistakes on your way to mastery will lose you games. Always be thinking about what your opponent’s plays tells you about the cards they have. These tendencies with different forms of card flows are a good start, but there’s plenty more out there to figure out.