For this week, I was playing with the—reader inspired, thanks for the feedback!—idea of writing a little metagame primer for the upcoming Bazaar of Moxen tournament like I did for Grand Prix Strasbourg in the past, but when I found myself pondering the latest big tournament results, one thing rapidly became overwhelmingly clear to me—the format is just too wide open right now to make a solid job of it.

I mean, yes, I could rewrite essentially the same article I did for Strasbourg and would probably still be correct about the most-played decks since Legacy can be slow to change in a certain way. Tempo decks are going to play a huge role—they always do—and there will be people playing all the other top decks we know and love (or hate), from Show and Tell and Storm to grindy BUG, Stoneblade, and Jund decks and everything in between.

However, where’s the value in that for most of you? You’re about as well off by clicking on the above link and keeping in mind that Deathblade was invented in the meantime. The metagame changes, the major players ebb and flow, but the basic skeleton of the format remains largely the same.

Sadly for the metagamers and luckily for the format, though, I fully expect to play at least half my matches against decks I wouldn’t ever think about putting into a metagame report. People have gone back to playing literally anything, be it pure speed-demon turn 1 kill decks like Oops, All Spells! or super-grindy disruption decks along the lines of Lands and Aggro Loam. Heck, I wouldn’t be surprised if some of my opponents end up trying to Smallpox or even Wild Nacatl me.

So instead of writing an article on the specific metagame for upcoming tournaments, I decided to approach the issue from the opposite point of view—how do I deal with decks I haven’t seen before? Today’s article will talk about the thought processes and assumptions that go into playing against decks we can’t instantly categorize. Interested? Good, follow along then!

Outside The Comfort Zone

If you play a lot of Legacy, your early-game thoughts almost any game hopefully resemble mine. Assuming I don’t get to Duress or Gitaxian Probe them, I wait for their plays with burning interest so as to gather my first clues to what it is I’m up against.

A lot of the time, you can identify your opponent’s deck as soon as they’ve taken their first turn, though sometimes it’ll take until turn two to have a reliable read. That approach only works if you actually know the deck your opponent is playing. What about something like this though?

Your opponent opens the game by cracking Polluted Delta for Scrubland[/author]“][author name="Scrubland"]Scrubland[/author] and casts Deathrite Shaman. At that point, I’d instantly put them on either Deathblade, Junk, or Deadguy Ale (Orzhov aggro-control) and play accordingly. But what happens when this is what you see when they’ve taken their next turn?

I hope you’d look at the board roughly as confused as I would. This sure looks like a classic Deathrite Midrange board, but why the heck is a Taiga and a Wild Nacatl on the table? Clearly this is not a deck I’ve seen before.

And that’s where our mind needs to start working overtime. Sure, we haven’t seen this particular deck before, but the cards our opponent has chosen to play tell their own story. It seems unlikely our opponent would be splashing for Wild Nacatl, and they’re clearly deep enough in black to make Dark Confidant a viable choice. They also plan on having red and white mana out with enough regularity to make Wild Nacatl the full 3/3, so they’re effectively a four-color deck at least.

That cheap 3/3 also has to be worth the effort—there’s a reason even Punishing Maverick generally ignores the purely aggressive one-drop. As such, the presence of Wild Nacatl alone argues strongly that we’re facing a somewhat unusual Zoo deck, probably one bearing a resemblance to the Big Zoo decks of old, with Deathrite Shaman taking over the role of Noble Hierarch.

As such, here’s a short list of cards I’d expect to be facing at that point of the game:

Basically all the high-quality Zoo cards that make the deck the aggressive powerhouse it is, plus Knight of the Reliquary because Deathrite makes the three-drop hurt the curve less.

And here are some things I’d be totally unsurprised to see turn up on my opponent’s side of the board but would only play around if I could do so for a low cost:

- Qasali Pridemage (too much utility to ignore in these kinds of decks usually)

- Tribal Flames (with them on four colors already, splashing a single dual to make this do five seems quite enticing; if I see an Island in addition to the other four colors, I’d move these to certain includes)

- Green Sun’s Zenith (and the assorted Dryad Arbor and Gaddock Teeg)

- Grim Lavamancer (if it doesn’t tax the yard too much in combination with Deathrite)

- Thalia, Guardian of Thraben (if I see one of these, I’d instantly downgrade the chance of seeing Green Sun’s Zenith because the two cards don’t work too well together and if you’ve moved far enough towards midrange to make the nonbo worth it, you should be better off playing straight Maverick instead of running Wild Nacatl).

- Abrupt Decay / Path to Exile (some form of big creature removal, though they might be mainly all in on dropping something bigger)

Things I wouldn’t expect even though they’re format staples that fit the color requirements:

- Thoughtseize / other discard (I’d put them on a Zoo strategy, and using your early-game mana for disruption just isn’t all that good in that deck outside of specific matchups—they might have them post-board)

- Swords to Plowshares (by including Wild Nacatl, I’d assume the life gain is a relevant disadvantage, which should lead to them playing either Abrupt Decay or Path instead)

- Cards that cost four or more outside of maybe a random Thrun, the Last Troll or Elspeth, Knight-Errant (I expect them to be aggressive enough for Nacatl to matter, meaning late-game tools aren’t really what they should be looking for)

As such, only seeing those cards, I’d assume they’re playing something close to this for spells, with a mana base full of duals and fetches:

4 Wild Nacatl

4 Deathrite Shaman

4 Dark Confidant

2 Grim Lavamancer

4 Tarmogoyf

4 Knight of the Reliquary

4 Lightning Bolt

2 Chain Lightning

4 Tribal Flames

4 Green Sun’s Zenith

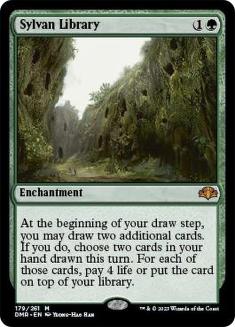

1 Sylvan Library

1 Gaddock Teeg

1 Dryad Arbor

Now, obviously I’m likely to be wrong on several aspects as to the exact contents of their list—they might be playing a weird port of a Modern Burn list, for example, and have a much lower curve and even more direct damage. But at the very least I have a good idea now what the game is likely to look like in the abstract. They going to put on pressure early and will start stumbling later in the game once their hand starts to empty and the impact of their efficient low-curve plays diminishes greatly. I’m also rather unlikely to be disrupted in my own plans. Just knowing this will help me to play this game accordingly.

What exactly "accordingly" means here obviously depends on what I am playing. With a combo deck, I’d choose lines that should allow me to goldfish as soon as possible, expecting just about no disruption. With just about anything else, I’d assume I probably need to play defense and try to gain control of the board—or at least stall it out—while playing around burn as much as possible, be it used as removal or reach.

Retro-Engineering

To make optimal plays, it necessary for us to know what options our opponents might have. Now, if they’re playing a deck we’ve seen a hundred times already, this is usually pretty easy to do. There are only so many commonly played decks even in a format as open as Legacy, after all, and anybody familiar with the format will usually be able to recognize the common ones after only a couple of cards and know what those decks usually look like.

If they’re playing something more rogue, things become a little more difficult. Essentially what we’re forced to do at the beginning of the game is to retro-engineer our opponent’s decklist from a few clues we’re being given. The trick is to constantly ask ourselves why the cards we’re seeing might be in our opponent’s deck. Once we’ve found a reasonable answer to that question, we have a working approach to how we should play this game and which of their cards are likely to actually matter to them.

It’s important to stay on our toes though. We may have an idea about what our opponent is up to, but we need to constantly revise our evaluation of their game plan. Whenever a new piece of information (generally a new card played) becomes available to us, we need to consciously check if our assumptions about what it is they are doing still make sense.

Say our opponent has so far cast Gitaxian Probe and Cabal Therapyed us on turn 1. Personally I’d put them on Ad Nauseam Tendrils and play accordingly. Suddenly, on turn 2, our opponent doesn’t cast a bunch of cantrips and instead announces Green Sun’s Zenith for one. Should we counter it if we can?

Well, I can’t see ANT running too many Green Sun’s Zenith targets, so the only thing that makes sense here is that we aren’t facing it at all but something midrangey that has decided to run Cabal Therapy and Probe for disruption. That being the new assumption, the Zenith target that would make the most sense for them to have here is actually Veteran Explorer, another card that synergizes well with Cabal Therapy.

In one fell swoop, all of our assumptions have changed. Instead of fighting to survive until we can somehow bring the game home, we suddenly need to worry about the mid and late game; fear what they might be doing once they hit four, five or even six mana; and think about ways of killing them before they can grind us out (or of turning things around to beat their long-term plans).

This new information may not answer our question if we should counter here in the abstract, but given an actual hand and deck, it sure makes things quite a lot easier. If I’m playing Miracles, I’m generally quite happy to see an Explorer trigger—Entreats trump almost anything fair people can do—while having it happen would be disastrous for a tempo deck. Now that I suspect that’s the result of Green Sun’s Zenith resolving, I can react accordingly. The secret is figuring out that Explorer is coming.

Technique

Now that we’ve seen how one might get from a minimum of information to an expected decklist in the span of a turn or two and are clear on what our job is against rogue decks, let’s look at the actual ideas behind extrapolating what might be in our opponent’s deck and what kinds of tells to look for.

Staples

The first thing we usually see from our opponents are their mana sources—after all, most spells won’t enter the stack without demanding some fuel first. With spells being of widely different power levels, there are some cards in every format likely to enter any deck playing the requisite color(s). I’d expect my opponent to have Lightning Bolts when they can cast them, and I’d be hard pressed to imagine them skipping Brainstorm if they’re in blue, whereas green still carries a strong indication of probable Tarmogoyfs.

None of these are sure bets—a deck’s inner workings and strategy can easily devalue even the best cards to the point of just not being worth it—just look at U/B Tezzerator and its Chalices—but as long as I don’t see an indication to the contrary, I’d expect them to be good enough to make the cut.

Shell Parallels

Similar to how certain cards will usually make it into lists that can cast them, a lot of different Legacy decks actually look quite similar outside of cosmetic differences. Last week I broke down the inner workings of Legacy’s tempo pillar, and this tendency showed up quite evidently there. Even if you only know RUG Delver, just seeing a couple of cards from Four-Color, U/W/R or even the Grixis Delver deck will allow you to conclude that they have a similar game plan to the known RUG deck and to therefore expect the tempo-style disruption of Stifle and Daze, Wastelands harrying your mana base, and burn waiting to sizzle your face or your own creatures.

Once this inherent similarity is discovered, playing against either deck shouldn’t be significantly harder than playing against a known entity. Just keep the additional options suggested by their actual mana base in mind.

Downgrades

If you’re playing Ponder, you will be playing Brainstorm. If you’re playing Chain Lightning, you will also have Lightning Bolt, and if you have Pact of Negation, you probably also have Force of Will. There are large numbers of cards that aren’t the best at what they’re doing but that are still good enough to see plenty of play thanks to the four-card limit. Whenever we see a card that is almost always strictly worse than another, we can safely assume our opponent will also have access to the superior card.

Strategic Includes

And then there’s the cards we’re looking for the most. These are cards that enable plenty of different decks but also require so much of a commitment to a particular kind of strategy or set of cards that their presence generally indicates others being present.

If an opponent opens on Ancient Tomb, not only is it likely that we’re also facing City of Traitors (the downgrade) but also a number of spells with high colorless costs. If an Ancient Tomb comes down, I’d expect my opponent to also have Chalice of the Void in their deck (though Sneak and Show or Painter might foil that read) as well as at least a reasonable amount of spells with high colorless costs. If they need fast mana enough to run Lotus Petal, they’re probably a combo deck. City of Brass and other gold lands similarly point to a deck with a heavy early-game focus and some broken interactions among multiple colors.

Exploration clearly signals that they’re planning to enable shenanigans by dropping multiple lands per turn, and if they play Deathrite Shaman, they probably plan on the game going long enough to actually use it, so they probably won’t be killing me on turn 2 but instead will have ways to interact somehow to make the game take enough turns for Deathrite to matter (or they could just be on Elves and I’m planning for a totally wrong game—c’est la vie). Similarly, playing Mother of Runes only makes sense if there are enough valuable creatures to protect with it, telling us a lot about what our opponent is up to.

The Wild Nacatl in our opening example functions like that too. Because a one-mana 3/3 is good but only useful when approaching the game in a certain way, it allows us to make the largest number of assumptions of all the cards in play. The Nacatl more than anything else our opponent has played gives our opponent’s intentions away and allows us to (hopefully) make the correct read.

Implied Interactions

Similar to strategic includes and staples, some interactions are obvious enough after putting some thought into them that we should be able to expect them. Say our opponent opens the game on Mountain followed by another Mountain and a Painter’s Servant naming blue on turn 2. The first obvious conclusion to make is that they’re running Grindstone. Even if their deck isn’t a dedicated combo deck, running a relatively weak card like Painter without also including the easy two-card combo kill just doesn’t make any kind of sense at all. There’s a lot more to realize here though.

Even if you’ve never heard of Imperial Painter before, a deck with several basic Mountains turning everything blue should set off alarm bells. Clearly they aren’t choosing a color at random; there’s some hidden goal here. If you’re thinking about the meaning of their plays deeply enough, you should know what to play around here. After all, they might just as well have put a sticker with a big fat picture of Red Elemental Blast on their Painter’s Servant.

Generally speaking, unusual cards that in general terms have too low a power level to see play are actually our best tools to unravel the mysteries (in contrast to the obvious cards covered above) in our opponent’s deck. Cards like Torpor Orb and Mox Diamond aren’t the best cards in the format, but they work so well with specific other cards that the most likely reason for opponents to include them in their list is them filling an important role as an enabler or synergistic piece (Phyrexian Dreadnaught and Life from the Loam / Land Tax respectively for our two sample permanents).

That being the case, these permanents in and of themselves eliminate a lot of uncertainty as to where our opponent is going. Because there are few reasonable ways to make them playable, their presence alone implies that of their complements, which in turn allows us to extrapolate large parts of our opponent’s game plan—which is exactly what we’re trying to do.

Progression

Another thing that can tell us a lot about our opponent’s game plan is the progression of their plays. Independent of which lands end up casting them, if my opponent spends their first two turns casting three blue cantrips, I’m putting them on a combo deck of some kind.

Now, they might be a tempo deck with a particularly uncooperative draw, but any deck that allows the opponent free rein over turns 1 and 2 should have a comeback planned out—and in decks heavy on cantrips, that comeback generally happens to be something that gets the opponent dead ASAP.

Similarly, if my opponent isn’t playing anything but fetch lands during the first three turns, something is clearly up. No viable Legacy deck just doesn’t have anything to do during the early game. Instead, what they have in hand has to not have enough value to cast now, meaning their hand is likely full of reactive cards, be it countermagic, removal, or an incomplete set of pieces for a combo win.

If they were threats, they’d probably have played at least some of them, and if they were some convoluted combo kill, they’d probably either have cast library manipulation by now or would have tried to kill me (assuming I’m not sitting around representing countermagic and Stifles like a boss). Sitting around doing actual nothing (in contrast to improving their hand with cantrips or doing "nothing") generally doesn’t favor the combo decks of the format.

We still can’t rule out the threat of a powerful combo kill, but if I had to decide upon a play here between setting up to win a long grind, which gives them an opening to go off, and one that is safe versus combo but weak to opposing interaction, I’d go with the former.

Roughing Up Rogues

And that’s how to approach unknown opponents in a nutshell. Whatever it is your opponent is doing, expect there to be some method to the madness. As the game moves along, they can’t help but give you information to work with. Which colors they play, what kinds of cards they have in their deck, what metric they’re trying to get ahead on—essentially telling you why they win—and when and how they’re planning to actually end the game.

Your job—and you really don’t have a choice but to accept it—is to maximize the information you glean from these breadcrumbs and draw strong enough conclusions to enact your game plan while preempting theirs, be it by using well-placed disruption or just good old killing them first.

Where to focus your efforts at gathering information mainly depends on your own deck. If you’re playing Storm, you could care less about their removal options and beatdown creatures, but their likely disruption matters infinitely. A Delver deck, on the other hand, is most interested in figuring out how to best attack their resources while clocking them. Maybe they can’t ever beat a Nimble Mongoose, or maybe all that matters is to stay alive because once you’ve stopped them from going off, any threat will take them down eventually. Or they could have an incredible mid to late game and all you care about is trapping them on low mana for as long as possible because once they get going, you just won’t keep up.

Identifying these situations will make or break your Legacy tournament most likely—the number of decks in the format is large enough that it’s nearly impossible to know them all, and people somehow insist on building ever more viable decks to add to that pool. Only by keeping in mind that our opponents are generally trying to win the game just as much as we are can we make reasonable guesses as to what exactly it is they are doing. And only with that knowledge can we react accordingly to stymie their efforts and enact our own success.

When faced with the unknown, we need to combine what we know well with the fleeting impressions of options we know exist but haven’t seen used to rapidly turn the unknown into but a reflection of something we understand. Once that’s done, the rest is just playing the game.

That’s it from me for today. I’d be happy about any feedback you care to share and once again any suggestions as to what you’d like to read more about. I haven’t had the time to answer as many of last week’s comments as I would have liked so far (I hopefully will get there before this is published), but I sure do read them all.

Until next time, de-robe a rogue!