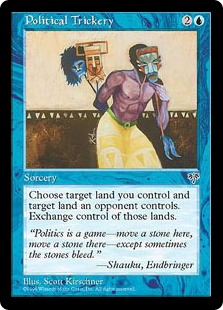

Politics in the context of Commander is a concept fraught with difficulty. It’s one of those terms that can have a broad swath of meanings between different people or specific subcultures within the format. To some it is an evil to be avoided at all costs; to others, it’s the best part of the Commander experience. Regardless where you sit astride a very long fence, political interaction is an inherent part of our format. What follows is a guide for navigating that minefield, looking into a few different categories of political interactions.

The very nature of a multiplayer game means that politics and bargaining are built into its DNA. From the simplest “I’ll take care of them if you leave me alone next turn” to the most complex and specifically worded deals, there are many flavors of Commander politics—from the friendliest to the most cutthroat. Let’s take a look at how to maximize the value in your deals.

The first piece of advice is to never break your word. First, you just don’t want to be that person, especially in a social format. If you demonstrate that you’re sketchy, you’re going to find yourself on the outside of lots of groups. Additionally, that’s not setting a particularly positive tone for the folks you want to play with. Second, the long-term value isn’t there. If you break a deal, you might get an advantage or win in one game. The downside is that people will remember, especially if you’re in a regular play group. People will be less likely to trust you, and you’ll spend a long time living it down.

I learned this lesson very early in my adult life. The first time my ex-wife and I ever played a game together, it was Risk, playing with a new group of friends. The two of us were in Australia early, and I offered her a non-aggression pact. She said sure. After I built up a bunch of forces, I broke the deal at a strategically convenient time. She didn’t get angry about it, but every time we played a game of any kind, if it was possible to screw me over, she’d say “Remember that came of Risk?” The lousy part of the whole affair is that I don’t even think I won that game.

That experience was part of what led me to the point of never breaking any agreements in a Commander game. While I’ve engaged in the Well-Worded Contract (see below) a few times, I strive to always stay true to the spirit of the agreement. I believe that it’s set a positive tone for the games I play in as well as made it easier for the people I play with to trust the deals I make with them. Sure, there will always be a bit of skepticism when you suggest something, but knowing that you’re honest will make it more likely that the other person agrees.

While politics generally impact the current game you’re playing (especially if you’re sitting with strangers you might never see again), they can also spill over to other games. Whether you’re the friendliest deal-maker or the shrewdest negotiator, your group will pick up on your tendencies and react accordingly. If you’ve become exacting in how you word things, expect them to figure that out. How you play politics in any single game may very well impact how you get to play them in subsequent ones.

The Friendly Agreement

There will be time when you’re not particularly under the gun for anything, but someone will ask you for a favor, like, “Hey, will you take one damage from Shadowmage Infiltrator so that I can draw a card?” Especially in an early game situation, this is probably harmless.

The most classic of the Friendly Agreements is trading Solemn Simulacrum. The other player gets a positive benefit for either attacking or their creature dying. You get the card draw from the Solemn. In the Friendly Agreement, everybody involved in the agreement wins.

The friendly agreement is never loaded or subject to backfire. It’s straightforward, and the gains are positive for both players, but not so egregious as to upset the other two players. In fact, a Friendly Agreement doesn’t intentionally hurt a third party.

There are plenty of cards that create friendly agreements, like Strixhaven’s Secret Rendezvous. Cards like Howling Mine, Temple Bell, Mana Flare, Font of Mythos, and Horn of Greed can be an effort to create a positive political environment for their controller, but you’re more likely to earn stronger ties by targeting players instead of giving out gifts to everyone. Be warned that there are some cards that look like they’re friendly, but are actually traps, like Tempt with Discovery. Many of those cards turn into Group Hug decks that aren’t as nice as they might seem. Even a card like Forbidden Orchard can become an offensive weapon (like if the player has Defense of the Heart).

The cards with tempting offer are a great study in politics; it’s a kind of prisoner’s dilemma. In general, the best move is for no one to take the offer. It only takes one wildcard, however, to mess up the equation. No one wants to be the only player left out. The first player to choose generally sets the tone. By the time it gets to the third player, their choice is likely made for them. If at least one of the first two has taken the offer, they might as well take it too. When a tempting offer card is played, I like to have a discussion before the spell resolves. If it’s Tempt with Discovery and someone says “I know I shouldn’t take it, but I’m mana screwed,” you know how things will go.

Sometimes, the Friendly Agreement is simply an offer to help someone out, just to keep them in the game. If someone is getting attacked for exactly lethal damage, you could activate Phelddagrif and give them some life. You might spend a Fog so that they’re still around to help you against a common enemy. This is especially good if your battlefield state is significantly better than theirs but not as good as the enemy’s.

The value of the Friendly Agreement is in building positive political capital. You’re getting a small benefit, but that card or other bonus is just part of what you’re getting. You’re also acquiring a little bit of good will. It might not buy you out of big trouble, but you’re positively presenting yourself to the other player.

The Not-So-Friendly Agreement

In this one, your mutual agreement is to the detriment of a third party. It may also be beneficial for the two of you—as is anything that damages an opponent—but it’s really about dealing with the threat from the other player.

A common example here is you and your co-conspirator smashing creatures into each other when one of you have Grave Pact or Dictate of Erebos and someone else has a single, scary creature, like a Voltron’ed-up commander.

There’s the variant on the Friendly Agreement theme when you ask someone’s help to get a positive benefit for yourself but in order to do so, they have to help you hurt another player. For example, you have a Baneslayer Angel. Opponent A has an Icy Manipulator and Opponents C and D have one flier each that’s bigger than your Angel. You want that lifegain, so when you go to combat, you ask Opponent A to clear the way so that you can bring your life total up a little. It’s not necessarily about attacking that player, but they get dinged anyway.

The value of the Not-So-Friendly agreement is normally more situational. It’s not about building up any kind of long-term capital. It’s about problem-solving in the moment.

The Well-Worded Contract

This is one where you have to be really careful. For example, if someone asks you to do something for them and “I won’t attack you next turn,” make sure that you get a clearer agreement. After all, if they Fireball your face, it wasn’t an attack as far as the Magic rules go. Still seems pretty attacky to me, but I get it.

When someone says such a thing, I make sure that we agree that “attack” also means not messing with me or my stuff. I almost said “target” there, but that also has a specific Magic meaning, so be as clear as possible. I’m not suggesting sitting down and writing up something like you’re old-school D&D players working on wording a Wish, but make sure you’ve left as little room as possible for angle-shooting.

On the other hand, you can do some angle-shooting on your own. I think it’s appropriate to parse your terms very specifically when you propose a deal, but not when someone else does. If another player says “I’ll do such and such if you don’t attack me,” then I’ll take that to also mean not Comet Storm-ing them into oblivion or nuking their battlefield.

If I, however say “Do this thing and I won’t target your creatures,” then I don’t see it as breaking the agreement by casting Damnation. In the first example, you’ve taken someone’s words, decided on their meaning despite the gray area, and not given them a chance to clarify. In the second, by offering the first foray, you’ve given them opportunity to change your terms. Note that I would only do this with experienced players who know that “target” has a specific meaning within in the game. To wreck noobs with this move is completely uncool.

The upside of the Well-Worded Contract is mostly immediate or near-term. It’s about getting something you want or doing something the table needs, getting benefit and/or protection after an amount expending resources that would leave you vulnerable.

The “Let’s Get ‘Em!”

This one goes from relatively simple to pretty involved. In the most straightforward scenarios, it’s a request to tap or remove a blocker so you can get an attack through. In this kind of case, the benefit to the other player is that you’re reining in or possibly dealing lethal damage to the biggest threat at the table. At the more complex end, it’s banding together because someone has become the archenemy.

Of course, you have to consider the threat assessment question. Part of your political toolkit is sometimes going to involve demonstrating to and convincing the other players who is currently the greatest (or sole) power at the table. Commander games have complicated and messy battlefield states. Not everyone is going to see everything similarly, so your verbal skills will have to be on display. Don’t get salty if folks disagree with you. Simply position yourself as well as you can depending on what kind of deck you’re playing or your position relative to the threatening player.

The benefit of Let’s Get ‘Em is pretty straightforward: you’re taking out the big threat.

The “Strategic” Scoop

I’m not 100% sure that this one is politics, but it’s close enough to want to bring it up. It can certainly have political implications. Also called by less-than-friendly names, the “strategic” scoop is conceding to rob another player of positive benefit. Probably the most well-known example is something attacking you for lethal damage with a bunch of creatures that have lifelink. You scoop, ending up with the same result for you—you’re out of the game—but the other player doesn’t gain the life.

This maneuver is highly controversial, and to be honest, one that I detest—so much so, that if you perform it in a game with me, you won’t be invited back to play with me again. Some others have a much higher tolerance for it than I do; my best advice here is to know your audience. In some circles it’s fine, in others not so much.

To me, this is sketchy at best. Some folks will argue that according to the rules, a player can concede at any time. Of course, once they invoke “according to the rules,” you know they’ve moved into rules lawyer mode. I prefer an organic end to the game, one that involves the natural outcome based on play of the game and interaction between players. Once again, the “technically correct” crowd will say that it’s a legal action. You’re right, and I’m of the opinion that you’ve broken the social contract of the game nonetheless. I understand and respect that some folks think differently.

I believe rage-quitting also breaks the social agreement that you made when you agreed to sit down to a game. If your deck isn’t working or whatever, stick it out for the benefit of the other players in the game. Your presence actually matters. By just leaving, you could swing the outcome of the game in a very different direction. I’m not trying to tell you what to do with your time here. Just really think about the consequences of your actions.

Miscellaneous Cards

There are political cards that don’t neatly fit into any categories. Often, they let opponents choose if they get a bonus, but if they do, there’s a cost. I’ll focus on two from Commander 2021, one new and one a reprint.

The reprint is Orzhov Advokist. At the beginning of your upkeep, each opponent gets to choose whether or not they put two +1/+1 counters on one of their creatures. The cost is that until your next turn, they can’t attack you or your planeswalkers. There are times when the choice is clear for them; they had no intention of attacking you in the first place, don’t have any creatures, or they’re about to launch an alpha strike on you. Otherwise, they have to weigh the cost versus the benefit. Two counters doesn’t seem like much value for not attacking that player, but then again, there are other players to attack.

Somewhat along the lines of Edric, Spymaster of Trest, Breena, the Demagogue creates an incentive for players to attack your opponents. The benefit is being able to draw a card (and everyone loves cards). The major cost is not attacking you. The secondary is letting you put two +1/+1 counters on one of your creatures. If it’s Breena (and there aren’t so many situations where it won’t be), she can get very serious very quickly. The other players have to weigh the benefit of drawing cards against the eventuality of Breena becoming a wrecking ball.

Politics are a big part of social Commander games. They’re about securing agreements, truces, or détente with other players in order to improve your position in the game or to avoid getting knocked out it. Forcing others into certain plays (like Counterspell Chicken) isn’t really politics, although it’s a valid part of the game. Politics involve being interactive outside the game in order to do things inside it. Knowing when and where of how to successfully use politics will be of great benefit to all your future battles.