Howdy folks! John Dale Beety and I are back working collaboratively for 2024, and first on our docket is poring over everything we’ve seen for Magic’s upcoming set, Outlaws of Thunder Junction. As per usual, I’ll be digging into the early art we’ve seen, and John Dale will be tracking the story, both of us in an effort to try to orient our gaze to what we’re about to experience as Magic takes on the Wild West.

The Art Lens

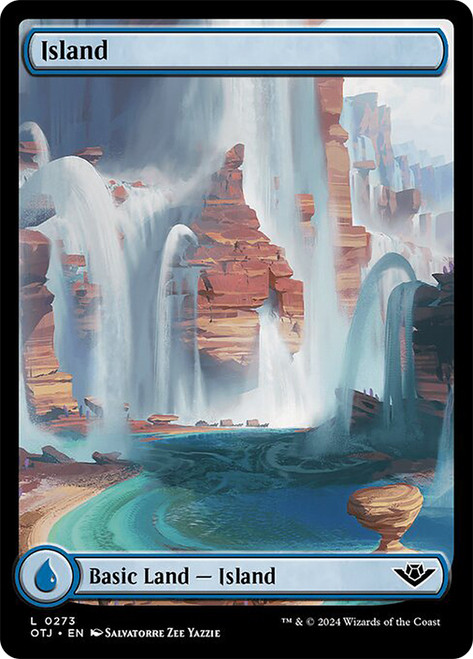

“Landscapes Support Imagination” – Salvatorre Zee Yazzie

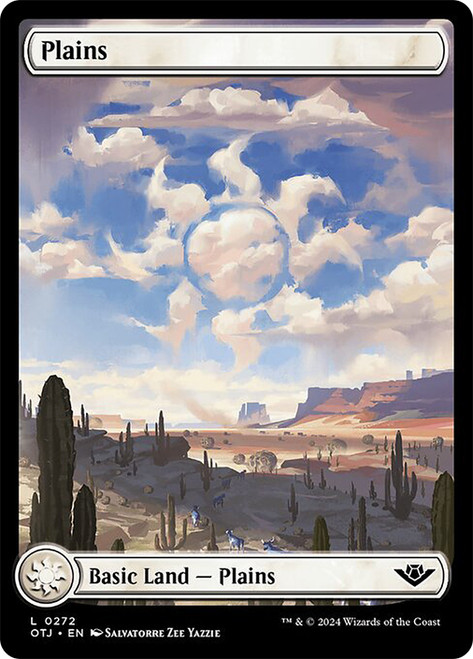

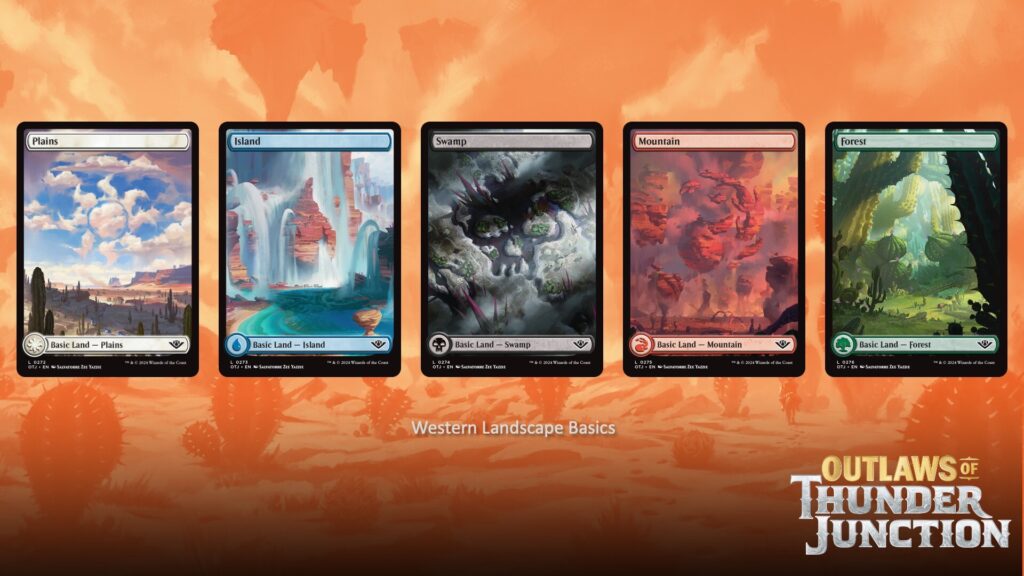

We’ll begin with the Western Landscape basic lands, previewed at MagicCon Chicago and illustrated by Salvatorre Zee Yazzie. Yazzie is Diné, a member of the Navajo Nation, who grew up on a reservation in northern Arizona. He was one of Wizards of the Coast (WotC)’s first concept art interns a half decade ago, and has made his Magic debut this spring, first with cards in Fallout, and now with this brilliant cycle of basic lands that are signpost illustrations of Thunder Junction.

I was able to speak with Yazzie via phone ahead of this article, a beautiful conversation of where he came from and how that has shaped him into the artist we see before us. For Yazzie, these landscapes were a test of range and malleability, as he called it; as each needed to be decidedly the same area and convey the mana symbol with subtlety, but not so much that they couldn’t be parsed at first glance.

He mentioned folks are used to seeing clouds as symbols, making the Plains perhaps the most recognizable of the set.

The Island (my personal favorite) and the Mountain are less believable in his opinion, but blend the natural landscape of the West with a fantasy ‘what could,’ giving them an extra bit of illusion.

The Swamp is the only ‘top-down’ perspective; we’re viewing the symbol from horseback, or at the very least by foot. It’s both legible and mysterious.

And the Forest pulls in the cacti that pop up through the other visuals seen thus far, a lush, mirage-like image that ever so slightly reveals the green mana symbol once you look completely through the image.

Yazzie noted he drew his greatest inspirations for this set from the work of Edgar Alwin Payne, an American Western landscape painter of the early 20th century best known for his impressionist views of California, Arizona, and the Southwest.

Payne’s work set the stage for this reimagination of a fantastical West, and Yazzie’s work provides an incredibly rich backdrop, steeped in realism, for this newest setting.

Rain, Steam, and Speed

All aboard!

Our next stop is a piece of marketing artwork, the flip-up standee for the booster box and the header image for the Card Image Gallery on the mothership. While we see Oko front and center, it’s the rushing piece of technology in the background that is of peak interest: a train.

With Vraska at the helm, it tells us there is likely to be some sort of railroad associated with Thunder Junction, whether it’s a major depot or just a stop along a much longer railway. Interestingly enough, you’d be hard-pressed to find artwork of the American West depicting trains; they didn’t become the subject of American artistic movements until the Art Deco period of the early 20th century. Those painting in the 19th century were Romantics, focused on serene nature and sprawling landscapes; a piece of steam-powered machinery like this would have been the furthest from their focus.

However, if we look to where steam-powered rail began, in the United Kingdom, we find perhaps the single greatest train painting in art history, by one J.M.W. Turner.

Even though it’s not depicting the American West, it evokes all the associated emotions by way of imaginative motion and innovative color. We see a locomotive of the Great Western Railway charging through the foreground in a rainstorm. It’s standing still, and yet we know it’s moving fast, a technological contrivance that would change the human landscape forever. The locations are different, but the eventual impact is the very same.

While it’s more than likely the train we see here is purely anecdotal, adding to the flavor of the setting versus playing a major role, its presence reinforces the idea there is a technology at play in this new world. This idea is further emphasized when we look at weaponry, and we’re not talking about guns as we see them in our world.

Draw, on Three!

Guns, excluding recent Universes Beyond releases (which do not count towards the game’s overarching mythos), are not found in Magic: The Gathering. The sole exception is Portal Second Age, where several cards explicitly illustrate modern-esque firearms, despite being set on the sword-and-sorcery-laden plane of Dominaria.

Since then, Magic has been extremely careful using guns in their illustrations; in almost every case since, it is easily discernible that the device runs on magic (versus bullets and powder), and that it does not resemble any sort of real-world firearm. Based on the early looks of Outlaws of Thunder Junction, that protocol will continue, though we’re flying as close to the sun as humanly possible, based on early reveals at MagicCon Chicago.

A bandolier-wearing centaur with a part-Peacemaker, part-Winchester, double-barrel-but-not-like-that, is a unique concept as a point of departure. How does it work? Not sure, but it looks like it’s going to do some damage.

That sure looks like an energy sword, Kellan, my boy. Though again we see a bandolier full of casings on his belt. Is this for visual continuity? Or does he have something shooty underneath his trench coat? Or can you shoot things with a sword? A pistol sword is a thing, with varying iterations from a traditional sword with a pistol along the blade to an Elgin pistol with a Bowie knife under the barrel (with alleged but unconfirmed ties to the Old West). We know only what we see; we still haven’t seen how it actually works.

Moving on from swords, we have a… crossbow? The use of crossbows as a weapon largely died in the 16th century with the rise of gunpowder, and this was not a technology commonly used by Native Americans. However, the ‘magical-ness’ of the weapon is clear, which means perhaps it’s going to be something entirely new, just for this set.

Looking past the ‘guns,’ a cacophony of blades formed the bulk of the remaining weapon-focused previews, from the twin daggers wielded by our pro/antagonist Oko, seen on the Prerelease Pack…

…to the Sword of Wealth and Power seen as a part of The Big Score. It would seem that Thunder Junction likes big swords, and they cannot lie.

From traditional landscapes to unusual modes of transportation, and all the things that may or may not go pew-pew, we’ve only gotten a taste of what could be coming in Outlaws of Thunder Junction. The set no doubt seeks to tell a taller tale, and that’s where JDB picks up our story.

The Story Lens

Outlaws of Thunder Junction is, as WotC says, “Magic’s first Western-themed set”. The Western, however, is a broad genre, and crossovers between the Western and various flavors of speculative fiction are nearly as old as the Western itself. I’ll cover the history of those crossovers, try to pinpoint where in the American West is Thunder Junction’s biggest inspiration, discuss how various Western subgenres fit into the set or don’t, and examine whether yet another genre is lurking in the set’s mashup.

Weird West

“Weird West” is an umbrella term for Westerns with elements of fantasy, horror, or science fiction. Owen Wister‘s 1902 novel The Virginian largely codified the Western as a genre, and the first stories in the Weird West tradition emerged in the 1930s alongside specialist science fiction magazines, radio serials, and low-budget “B movie” sound films.

In 1932, a full 85 years before the release of Ixalan (and five years before the publication of The Hobbit), Conan the Barbarian creator Robert E. Howard made a conquistador vampire the central evil of a short story, “The Horror of the Mound“, set in rural Texas. Three years later, “singing cowboy” Gene Autry had his The Lost Caverns of Ixalan moment when his character discovered an underground civilization in the film serial The Phantom Empire.

The Western’s popularity peaked in the mid-20th century, first with higher-budget Hollywood films and then with television, and these productions sometimes dipped into science fiction and horror. Going in the other direction, the original version of speculative anthology series The Twilight Zone borrowed from Westerns for several episodes, with “Mr. Garrity and the Graves” the closest to a fantasy Western.

While Westerns as a genre declined in popularity from the late 1960s on, they never went away fully, and neither did the Weird West. Examples include 1970s comic book Weird Western Tales, 1980s Saturday morning cartoon BraveStarr, 1990s film Wild Wild West, 2000s television series Firefly, and 2010s film Cowboys & Aliens.

Which West?

The idea of a “Western” covers a great deal of physical territory. Almost any place in the contiguous United States west of the Mississippi River has Western potential, including Missouri (starting point of the Oregon Trail and the Pony Express), South Dakota (site of the “Treaty? What treaty?” Black Hills gold rush and Deadwood), and the aforementioned Texas (where Lonesome Dove begins). The early Outlaws of Thunder Junction previews, thankfully, offer two major clues that help narrow down the set’s key worldbuilding inspiration.

Clue one: the multi-armed cactusfolk and the giant cacti in the landscape. While massive cacti are, per the National Park Service, “the universal symbol of the American west“, the range of the saguaro cactus is surprisingly limited, with natural populations only in southwestern Arizona, extreme southeastern California, and the neighboring Mexican state of Sonora.

Clue two: the character Annie Flash draws inspiration from the Diné of the Navajo Nation. The Dinétah or traditional homeland of the Diné (as opposed to the smaller Navajo Nation borders) covers parts of the U.S. states of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah.

Those clues, plus the general red-rock look of various Thunder Junction artworks, point to Arizona as the main location inspiration. The state’s varied geography offers all the landscapes Magic demands. Further, Arizona has a long history as both a setting for Westerns and a filming location, with the original 3:10 to Yuma just one example of both. (That’s Yuma the city, not Yuma the protagonist of Thunder Junction short story “No Tells“).

An Arizona inspiration would lean Thunder Junction toward a “desert boomtown” West, rather than a “rancher” one populated by cowboys. There’s still plenty of the setting and set to see, though. It’s too soon to call this one all hat, no cattle.

Which Western?

Any genre with over a century of history cannot be a monolith, and the Western is no exception. Because Outlaws of Thunder Junction is an inherently visual experience and most players’ experience of the Western is visual, this section will focus on film and television over print and radio.

At the height of the Western as a popular genre in the United States, it was under restrictions in what content and themes it could display. For Hollywood films, the Hays Code made it difficult, though not impossible, for Westerns to deal in moral ambiguity or anti-heroism. Television was regulated by the FCC, which had strict rules on obscenity. As a result, up until the mid-1960s, the Western had a reputation for family-friendly entertainment, suitable for general audiences, with clear good triumphing over clear evil.

In the 1960s, the content of Western films shifted dramatically. “Spaghetti Westerns” filmed in Europe (often Italy, hence the name) did not have to follow the Hays Code, leading to films such as The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. In 1968, today’s MPA ratings system replaced the Hays Code, freeing American filmmakers to create edgier Western fare, such as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Since the 1970s, the revisionist Western, which rejects the black-and-white simplicity of Westerns at their apex, has dominated the genre. In revisionist Westerns, protagonists can be antiheroes, villains can show true villainy, and Indigenous characters can have personalities. Outlaws of Thunder Junction, which teams up several notorious Magic villains, sits squarely within this revisionist zone, which has lasted longer than the pre-revisionist Western and become its own tradition.

Heist West

That team-up of disparate villains suggests a film tradition that is not specifically Western, or even Weird West. The way Streets of New Capenna was, in the words of Sam from Rhystic Studies, “a pastiche of a pastiche” imitating tropes that were themselves imitations, Outlaws of Thunder Junction is a mashup of a mashup, the Fantasy x Western “Weird West” mashed up with the heist film.

On a checklist of heist film attributes, Thunder Junction is ticking every box. Oko is assembling a team of villains with varied skills: Tinybones, the Pickpocket; Rakdos as “the muscle”; and so on. (Bonus points for Annie Flash coming out of retirement for “one last job”.) This team wants to be the first to breach a vault of riches on Thunder Junction and loot it, and this task’s planning and execution will be the plot focus (while also paying off Kellan’s search for his father). Kellan’s essentially “good” personality almost certainly will clash with that of the selfish and vain Oko, to say nothing of the conflicts between the rest of the villains.

Since even before 1903’s The Great Train Robbery, Western films have depicted heist-like activity. The Wild Bunch (1969) is a classic “one last job” heist film that’s also a revisionist Western. There’s even a horror-Western heist film, Dead Birds (2004). Outlaws of Thunder Junction has an obvious debt to Westerns and fantasy, but it seems to owe just as much to the original Ocean’s 11; Shivam Bhatt calling the story “Oko’s Eleven” is both hilarious and on-point.

Finally, the Ocean’s 11 comparison may offer a clue to Thunder Junction’s ending: in the 1950s and 1960s, which codified the heist film, the Hays Code mandated that criminals never profit from their crimes, hence the trope of the heist or its aftermath falling apart. Will the efforts of Oko’s Eleven come to nothing, as in the original, or will it be more like the 2001 remake, where they get away with everything?

Feeling the Thunder

Outlaws of Thunder Junction lies upon a bedrock of over a century of the Western as a genre, telling stories through print, radio, still pictures, and the moving kind. In doing so, it seems to have adopted many of the visual and narrative conventions of revisionist Westerns, and even heist films.

What matters most is how WotC and its artists, writers, and designers handle those tropes and make them uniquely Magic. Their summed efforts will make Thunder Junction either a fresh spin on the source material or a retread of a retread, a future classic or a forgotten B movie. In this regard, I’m not revisionist but traditional, rooting for a happy ending.