The other day, I was out on a walk, listening to old episodes of Mark Rosewater’s Drive to Work podcast. I find Rosewater’s work to be an invaluable resource for Cube designers. I don’t remember the topic of the episode I was listening to, but he paraphrased a famous quote of Michelangelo Buonarroti that really speaks to the fundamentals of Cube design. The actual quote, translated into English, is as follows:

The Sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.

Michelangelo Buonarroti

That’s exactly what designing a Cube is. You’re taking the game of Magic, and removing the parts that are not your Cube. I find that designing a Cube is generally thought of as an additive process. After all, the way we come up with lists of cards is to add the cards that we want to feature as we think of them. If you look at this process a bit more abstractly, though, you’ll see that it’s actually subtractive.

Take Me Out

Many Cubes start with a guiding theme or principle. For example, some players curate Old Border Cubes. In declaring this theme, you have taken the game of Magic and removed every card without an old border printing from your Cube. Want to build a Pauper Cube? You’ve removed all non-common cards from Magic. You get the picture. The clearer the vision you have for your Cube, the more Magic cards you’ve removed from your pool before you’ve started writing cards on a list.

I’m curious what manner of title the editors will come up with for this article, and in case the picture I’ve painted to this point and the title they’ve selected haven’t made things clear, today’s topic is how to approach cutting cards from a Cube. Personally, I love cutting cards. As I cut cards from a list and add new ones, the Cube moves closer to whatever my vision for that Cube is. This is similar to my philosophy on bans in Constructed, and the importance of removing problematic cards to expand the relevant percentage of the card pool.

You’re Up and You’re Down

It’s far more popular for Magic players to be anti-ban, and the interactions that I’ve had with other Cube designers have led me to believe that most Cube designers are much bigger on adding cards to their Cubes than cutting them. There’s a perception that a larger card pool in absolute terms means there are more playable cards, which would lead to greater replayability if true. When you account for power level disparities and cards that don’t play well together though, you start to understand how “more cards” and “more playable/enjoyable” cards are distinct categories.

As such, I’ve wanted to write this piece on how I approach cutting cards from Cubes and why I see doing so as important and good for the development of my Cubes for some time. If you’re the type to simply add more cards to your Cube as you like and let the size grow, I’m not here to yuck your yum. Rather, I’m here to highlight why keeping my Cube lists tight leads to the environments that I prefer, and to share my insights as to how others can embrace the art of cutting cards from their Cubes.

Before I get into it, I’ll own my bias for smaller Cube sizes. Today’s article is just as much about making swaps in a 540-card Cube as it is about doing so in a smaller environment, but I should state clearly that I strongly prefer Cubes that are close to the minimum number of cards to support the desired number of drafters. This is no secret, given all the work that I’ve put into Twoberts, but I don’t assume that everyone is necessarily familiar with all my preferences.

Every Second Is a Highlight

One of the major reasons that I prefer smaller Cubes is that, at smaller sizes, you can more easily highlight the qualities of Cube that differentiate the experience from retail Limited. A lot of Cubers make their way to Cube from Booster Draft, but for me and a different segment of the Cube player base, we enjoy that Cube bridges some of the gap between retail Limited and Constructed.

I find that players who come from a Limited background enjoy the practice of filtering out the noise and figuring out what they’re supposed to be drafting, while my background that’s more cemented in Constructed enjoys the experience more when a larger percentage of my draft pool is relevant to deck construction. A lot of folks prefer their Cubes to more closely emulate Limited, and again, this isn’t the sort of question that there’s a right answer to, and I’m not trying to offer that. I’m merely here to offer insights from my experience on my perspective.

Rares and Retail

To give some examples of the aspects of retail Limited that I try to keep out of my Cubes, let’s take a look at some of the rares in Dominaria United. Some of them call out specific things that just aren’t a part of the Limited environment in any meaningful way. Jhoira, Ageless Innovator and Rivaz of the Claw are two standouts in this way that are really only playable because they have decent stats. If you’re not intimately familiar with the set, you won’t know that everything after “menace” on Rivaz is broadly irrelevant.

Once you’ve played a good amount of the format, this sort of information is easy enough to maintain, but it’s a very homeworky aspect of getting into the format in the first place. It’s fun in a competitive way, but less fun in terms of “playing fun games.”

These sorts of cards show up in retail Limited because retail Limited has to serve a lot of masters. These cards are in the set for Standard, for Commander, to offer something properly evocative of the existing lore as we return to Dominaria, for any number of reasons that don’t pertain to Limited gameplay. Part of the beauty of Cube is that the cards that we include only have to serve the purpose of being fun to play with and meaningful contributors to our Cube environments.

House of Lords

The cycle of tribal lords is another good place to compare where retail Limited is disjointed in a way that Cube can strive to be more coherent. Valiant Veteran is actually a real card in this set. Being a 2/2 for two is decent, and stuff like Captain’s Call at common and a number of other Soldiers peppered throughout the set make the card a relevant aspect of the Limited environment.

Vodalian Hexcatchter, on the other hand, has close to zero support in the set. The card has Constructed applications, but for the purpose of playing Limited the card is as close as you can get to opening a Mudhole in 2022. Sure, there are some other Merfolk, but drafting a bunch of Volshe Tideturners and Voda Sea Scavengers is already enough weaker than casting Captain’s Call as a baseline that it’s pretty easy to understand why this isn’t a great idea.

Going to Extremes

When it comes to supporting tribal in Cube, we have a lot of advantages over retail Limited as Cube designers. The most significant of these is that we can go as heavy as we want on making sure that our tribal synergies work. For an extreme example of this, check out the Human Module of my Spooky Cube. Almost every single creature in the 180 is a Human or a Clone, so when you see Thalia’s Lieutenant, you know you’ll be able to get some relevant mileage out of it in an aggressive shell.

This approach both avoids the meticulous checking and double-checking of creature types as you draft and ensures that your synergistic payoffs are worth pursuing. More shallow support will often mean that just ignoring creature types and drafting abstract rates will work out better, and you find yourself in a pinch where the synergies and the raw rates present a conflict that asks your Cube if there’s room enough for both things. Pushing a theme to its extreme makes it clear that the theme belongs and is a relevant part of the Cube.

The Overlap

Of course, you might be thinking, “What if I don’t want to draft a Humans deck?” This brings me to a very important aspect of making small Cube sizes work, and something that increases replayability of Cubes of any size. There’s no better way to increase the replayability of a Cube than to feature archetypes with overlapping synergies.

The volume of Humans being high enough to make the type incidental makes it trivial to offer these overlapping synergies in Spooky Cube. You have token makers and sacrifice outlets for Sacrifice decks that are Humans, you have spells-matters payoffs that are Humans, you have sort of a flash Werewolf deck that’s lousy with Humans.

The draft lanes are more flexible because you’re not asking whether you want to draft a Sacrifice deck or a Humans deck; you’re by default drafting a deck with some Humans and figuring out what you want that deck to do. Making this work means removing cards from the Cube that would make this less true. Creature payoffs and sacrifice outlets that aren’t Humans aren’t appealing under this framework. So in pushing for overlapping synergies and increasing replayability in this way, it becomes essential to eliminate cards that don’t fit the mold.

Is or Is Not

The takeaway, then, on the topic of cutting cards and eliminating cards from consideration, is that once I’ve decided I want a Humans theme, I will heavily scrutinize any non-Human creatures. Further, any effect that is available from a Human card should be prioritized over any non-Human source for that effect.

Humans specifically gain a lot from having great options in all five colors in this respect, but there’s also a good case study on Zombies in the Monster Module. There’s room for some stuff like Boneshredder and Shriekmaw for the way they support delirium and Spider Spawning, but most of the black creatures in this module are Zombies to make sure that Gravecrawler and Diregraf Colossus do their thing. Ravenous Chupacabra is not a consideration for this Cube, because Skinrender does mostly the same thing if you want to just take a creature on rate, while relevantly being a Zombie for the players who draft the relevant Zombie cards.

Ravenous Chupacabra appears in many Cubes, and serves as a good example of the sort of card you might feel pressured to feature in your Cube. That might take the form of peer pressure, or you might just believe these cards are things that you “should” feature. Ultimately, we all have two wolves inside of us as Magic players and Cube designers. One cackles with delight at dumpstering the opponent with Turn 1 Griselbrands, and the other sees the joy in supporting personal darlings like Xathrid Necromancer. I think it’s important to feed both wolves, but you’ll want to give them separate dishes.

Rebalance of Power

In fact, cutting generically powerful cards as I figured out how best to support my desired environment was a huge part of Spooky Cube’s development. Basically, any time a player did well with a deck that was agnostic to the Cube’s core themes, I cut at least one card in that deck from the Cube. In an early version of the Cube, Greg Orange went 3-0 with Azorius do-nothings, and I immediately cut five cards from his deck. This was a great way to stress-test whether I had put too much power in undesirable places, and an early mistake that I had made was featuring too many game-state-agnostic two-for-ones.

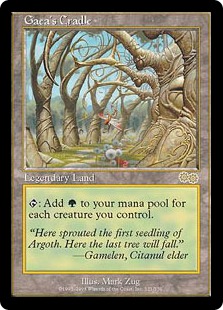

It’s one thing to include some personal favorites alongside the likes of Recurring Nightmare, Gaea’s Cradle, and other broken nonsense, and let them enjoy some wins on the backs of broken classics. It’s quite another to cultivate an environment where your favorites can thrive and do the carrying themselves. While it’s tempting to try to blend the cards you consider cool with the cards that you know are good, I would strongly advocate for making the cool thing the good thing in your Cube over this. That means if you want to let your darlings shine, the busted stuff sits on the chopping block.

With the sheer volume of Magic cards that I adore, it’s always made sense to me that maintaining more Cubes would lead to greater joy than maintaining larger Cubes. We keep the monsters together in the Vintage Cube box and figure out how to best support lower-powered and beloved cards elsewhere. My hope in sharing my various Twobert projects as I’ve worked on them has always been to share some of this joy.

Rethinking Green

I recently made a significant structural change to one of my Twoberts that illustrates today’s topic. Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty offered many new cards for my Artifact Twobert. In writing about the changes I made, I mentioned that I was considering retooling the green column. I really like the call that David McDarby made in designing the Magic Online (MTGO) Artifact Cube by excluding green spells. He said, “You know what, green mostly just destroys artifacts, and that’s really not part of what this Cube is.”

That spoke to me. The Artifact Twobert has some green darlings like Hardened Scales and Ancient Stirrings, and I like having access to some Oxidize effects as well as the additional green artifact lands, but the whole of the color felt lacking.

Earlier lists of the Cube went heavier on artifact removal, but there’s a tipping point when the gameplay really suffers. I drew a line early on, refusing to include Ancient Grudge in the Cube because I really didn’t want somebody who bought into the premise of the Artifact Cube getting demolished by a “Freshmaker” (this is an ancient deck name that predates even Ancient Grudge by a couple of years) deck. Similarly, I would never include Rest in Peace in the Spooky Cube because the idea is that I want players playing out of the graveyard. You don’t see Aether Snap in Carmen Handy’s Proliferate Cube, do you?

Further Rethinking Green

Pelt Collector and the other non-artifact counters creatures just didn’t fit aesthetically or mechanically. There’s too much in the way of artifact payoffs to value them highly, and many creatures in the Cube enter as 1/1s and don’t grow Pelt Collector or Experiment One. When a few more colorless options as well as options for the non-green colors trickled in, I said, Fine, some of these green cards just aren’t part of the Cube, and I’m cutting them.

I halved the total green cards in the Cube and reallocated those slots to other columns. Color symmetry is just one of those things that you’re “supposed” to do, but the non-artifact green creatures were superfluous material. I delighted greatly in finding a way to remove them while leaving space for the few green cards that did fit the mold.

Theme Week

Modern Magic design makes it easier than it has ever been to really dig deep and support a theme in Cube. Earlier, I dismissed Vodalian Hexcatcher by comparing it to Mudhole. This is a slightly hyperbolic statement about Limited, but the two cards aren’t remotely comparable when you start looking at environments where Merfolk actually matters as a creature type. This has the greatest relevance in formats like Modern, but Vodalian Hexcatcher certainly moves the needle for Merfolk in Cube.

Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty offered a lot for enchantment-matters themes, and was a great follow-up to Modern Horizons 2 in supporting artifacts as well. The pool of cards to support whatever you want to support is deeper than it’s ever been, and is growing all the time more rapidly than it ever has. It only makes sense to me to really push the themes that we love and to focus specifically on what makes those cards work.

Lessons from a Grixis Cube

Lastly, I’d like to close with some insights that I took away from having my Grixis Cube featured on MTGO back in 2019, which will also offer some thoughts on finding cuts in larger Cubes.

I’ve never really written a retrospective on this experience, but I learned quite a lot from this project. The major difficulty for me in submitted a list was that MTGO Cubes are required to be at least 540 cards (don’t ask), and my paper list before being contacted to submit a Cube was 360. It was fun and challenging to increase the Cube’s size by 50%, and in doing so, it was important to me to maintain what made the smaller Cube special. A lot of this was implementing some of the principles I’ve discussed today, with great importance placed on adding redundancy to existing archetypes as well as finding ways to make the archetypes overlap.

Supporting Archetypes

A big question I got regarding the Cube was how many archetypes it supports, with the implication being that the color restriction intrinsically limited the Cube’s replayability. In truth, the number of archetypes supported isn’t a question I ever ask myself. Every card in the Cube was carefully selected to be powerful in the environment and exciting to play with, and any homeworky notions of counting archetypes are easy to dismiss once you put fun game pieces in a player’s hands.

The subtext here includes another note on a category of cards that I find easy to cut, one that diminishes Cubes more than players may realize. Shoehorning too many archetypes with archetype-specific stuff with no other goal than to increase the volume of possible archetypes usually just increases the technically possible while reducing the quality of the decks that players actually draft. “How many archetypes should I support?” is a frequently asked question regarding Cube design, and my answer is that you’re usually better off forgetting the question.

I strongly believe that archetype depth is more important than archetype diversity. Archetype diversity leads to some exciting first picks as you try to get an idea of what you want to draft, but archetype depth keeps your options interesting as the draft progresses and leaves you with meaningful choices in deck construction. It’s tempting to fit all of your favorite archetypes into one Cube, but at some point you end up with archetypes that don’t overlap at all, and you’ll notice some players don’t have any meaningful decisions to make late in the draft. You might be surprised to see the replayability of a Cube increase as you actively cut archetypes from it to better support the deep themes that you really love.

From 360 to 540

Anyway, I went to work finding cards that would increase the Cube size while maintaining the broken Grixis cards environment I had cultivated at 360 cards. This involved a lot of oddball redundancy for Storm with cards like Sentinel Tower, some quirky Eldrazi support, and a pool of cards that allowed certain combos to co-exist in the same deck as well as ways to hybridize combo and control. My favorite card in the Cube is one that really highlighted how Storm and creature-cheating decks that can be hybridized in Aminatou’s Augury.

Of course, once the Cube went live, I felt deep anxiety, wondering where I had left room for improvement. For paper drafts I already had 180 cards on deck to cut, but I became invested in crafting the best 540-card version of the Cube once I signed on for the project, and I wanted to get some drafts in as well as listen to where other players thought I might have missed. Perception is reality, after all, and the opinions of the players matters at least as much as those of the designer.

Small Miss, Big Miss

A small miss was Chains of Mephistopheles. It seemed like a cool card that might get somebody to do something unusual, but drawing extra cards was far too central to the experience of the Cube for Chains to meaningfully contribute. The big miss was Narset, Parter of Veils. It similarly spat in the face of a lot of what the Cube was about, except it was also actually powerful to play.

War of the Spark was still pretty new at the time, and I hadn’t fully developed my loathing of Narset until after I had submitted the list. I still feel bad for everyone who had to play against Narset during Grixis Cube’s run. There have been tons of cards printed worth adding to the Cube between then and now that would lead to other changes, and honestly I kind of like the idea of really powering down the Cube with how many versions of powered Cubes we’ve seen on MTGO lately, but those were the two huge misses from my perspective at the time.

Disenchanted?

I got some feedback about enchantments being rather annoying at the time, given the limitations of a Cube without green or white cards, but I unironically consider that to be a feature.

The surprising piece of feedback that taught me a lot and gave me more to consider as I critically examine Cubes for cuts was how so many players hated True-Name Nemesis. Don’t get me wrong, the card is in many ways contemptible, but this feedback was eye-opening relative to this environment. In a Cube where Storm and Reanimator are heavily supported and Strip Mine and Timetwister are just hanging out, I did not expect a creature that attacks and blocks to be on anyone’s radar.

It just happens that the Cube is also relatively long on removal, and sometimes you find yourself in an attrition matchup. As charming as I find a Cube where Sulfuric Vortex will inevitably end the game one way or the other, facing down a lethal True-Name Nemesis with a Terminate in hand is a much tougher pill to swallow.

I thought True-Name Nemesis was fine because there were so many other, more powerful things going on. This doesn’t make the player who drafted a midrange deck and lost to a solitary three-drop creature with a grip full of removal feel any better. Sure, they’d lose to Storm or Reanimator just the same, but at least the combo player had to really commit to something, right? So True-Name Nemesis really cemented for me that, in addition to keeping my eye on the most powerful and the weakest cards in the Cube, the mid-pack stuff that just isn’t fun to play against is another great category to check out when making cuts.

Reinforcement

I presented a lot of information today, much of it not directly related, but it all amounts to different areas of focus as I cut cards from my Cubes to add new ones to try to deliver the most enjoyable environment that I can. Here are the major bullet points:

- You’ve already cut most of the Magic cards that exist from your Cube. This mindset will make it easier to cut further as your Cube evolves.

- The more defined vision you have for the type of Cube that you want to build, the easier cutting individual cards will be. Shifting perspective between broad and specific helps you solidify your thoughts on both.

- The only masters a Cube has to serve are that Cube’s own playability and personal preferences. You don’t need to include cards that are marginally playable or that there’s some inclination that you “should” include.

- You make the rules. If you’re really struggling with a specific color, creative solutions like imbalancing or eschewing entire colors are proven methods for designing great Cubes.

- Cards that don’t actively support your themes are expendable.

- Finding ways for your supported archetypes to overlap dramatically increases replayability.

- Archetype depth goes much further than archetype diversity in facilitating replayability.

- Winning with or because of a certain card is a lot different from winning and also having played a certain card. A creature that showed up in a game alongside Gaea’s Cradle doesn’t necessarily offer any unique value itself.

- The weakest and most powerful cards in a Cube are always good places to look for cuts, but cards closer to the middle of the power band that don’t offer fun play experiences are great cards to cut, too.

Taste and Principle

There will be stylistic differences between me and many other Cube designers, and there’s no accounting for taste, but these principles have helped me design a lot of Cubes with clear focuses and high replayability, while ignoring the popular notion that adding more cards is the effective way to reach this end. I don’t expect everyone to delight in cutting cards as I do, but perhaps this article will help to ease the pain that some of you feel when it’s time to update your Cubes. The cuts are every bit as important as the additions.