Whir Prison is a torture device made from cardboard. It’s hard to appreciate its underdog story, especially from across the table, but the tale of Whir Prison’s rise is the tale of Modern. A primitive list goes 5-0 in a League, raises eyebrows, and is soon forgotten… until the same player puts up another result, and another, and another. The narrative quickly shifts: of course the deck isn’t good; its pilot is just a savant. Their success is a bizarre anomaly. Don’t try this at home!

When people finally do try it, skeptics become believers. Their collective effort refines the deck until it becomes universally hailed as a contender — and a threat. As I look ahead to SCG Regionals this weekend, and the Open in Philadelphia after that, I expect to see players in the know stirring and whirring their way to the top.

After a few whirs of my own invention, I took a twist on this shell for a spin at the Modern Classic in Syracuse and was rewarded with a trophy:

Creatures (1)

Lands (19)

Spells (40)

I’ll explain why I chose this list and where I’d go from here, but we must step back first. To understand what this deck is, you must understand what it isn’t.

Lands (17)

Spells (43)

When Lantern Control made a dramatic entrance into Modern in the hands of Zac Elsik, nobody was quite sure what to make of it. The Prison archetype, a staple of old-school Magic, has been largely absent from contemporary play after designers realized that games are more fun when both players get to take part. The main culprit, Ensnaring Bridge, only swaggers through Modern because a public vote smuggled it into the format’s oldest set. The unique mechanics of the Lantern of Insight lock meant that even players who had been on the wrong end (either end) of a Winter Orb, Stasis, or Opposition had no frame of reference for what the deck tried to do.

Lantern’s inscrutability prevented players from picking it up but also from making the well-meaning comparisons that are so common and damaging. When other Prison decks arrived on the scene, one question was inevitable:

I don’t know. Aren’t apples just worse than oranges? Aren’t waffles just worse than French toast? Isn’t Lantern just worse than French toast?

It’s a natural question. Magic — and especially a format as large and diverse as Modern — is so complicated that it makes sense to unpack a new concept by relating it to something familiar. It’s a vital strategic question, too: as Patrick Chapin has reminded us over the years, the biggest and most avoidable mistake you can make in deck selection is picking a worse version of a known archetype. When the game’s best toil away in testing hours for weeks to find the deck with a 56% winrate rather than 54%, signing up with a strictly subpar strategy looks like lighting money on fire. It’s a fair litmus test to force any new deck to take.

Sadly, this often ends in dismissing decks based on a superficial similarity when they don’t share strategic goals and have a different spread of strengths and weaknesses. It becomes an exercise in lazy pattern-matching: Deck A and Deck B both play this card, so they must fall under the same umbrella, and you shouldn’t include this card in Deck A because “Aren’t you just Deck B then?”

This is fine when the two decks have the same core, though care must still be taken to ask the right questions: “Isn’t Jeskai Control just worse than Azorius Control?” isn’t helpful, while “Cryptic Command is well-positioned, but are the red removal spells better than Terminus against the most popular threats in the format?” is. It’s dangerous when those decks use overlapping tools for their own ends: Mono-Green Tron and Eldrazi Tron may share some namesake cards, but they have very little in common otherwise.

Normally, these differences are clear enough that attentive players can figure them out on the fly before disaster strikes. Prison decks pose a unique challenge, as effectively fighting them requires knowledge of how they operate and a long-term plan for breaking free. Turning up with the wrong tools is fatal.

Compare Lantern to the new kid on the block, supposedly its spiritual successor:

Lands (20)

Spells (40)

Lantern takes the fight to the opponent in every area of the game. Between targeted discard, the use of Lantern of Insight with Codex Shredder or Pyxis of Pandemonium to control the draw step, and Ensnaring Bridge and Pithing Needle to nullify anything that sneaks through that wall, no zone is safe. The lock snaps shut very quickly and denies the opponent the cards that could break it, meaning that any answer has only a short period of relevance.

It’s oddly reminiscent of an aggro deck: you present your threats in the form of lock pieces and force the opponent to have exactly the right answers at the right times. By necessity, the Whir of Invention lists contain a smattering of silver bullets that are either the best or worst card in your deck, but the main components of Lantern’s gameplan are universally relevant: Thoughtseize and Inquisition of Kozilek remain the broadest answers in Modern, and you don’t care what the opponent’s big finish is if they never get to draw it.

The easiest way to beat Lantern is to break one of those pincers. Cards like Ancient Grudge that operate out of the graveyard resist both mill and discard, requiring countermeasures such as Grafdigger’s Cage that are harder to find quickly and consistently. The library lock with Lantern can be fought with oddly specific tools – Chromatic Sphere of all things is terrifying for Lantern, as the card draw is tied to a mana ability that doesn’t use the stack and can’t be responded to (and because it’s seen in decks that are fundamentally solid against Lantern anyway), but anything that sifts through several cards at once or offers repeated instant-speed draw is useful there.

You can also fight the lock on its own terms through sheer redundancy: while Lantern will eventually assemble enough mill rocks to mathematically eliminate your chance of drawing an answer, one copy has a shaky hold on the game at best if your deck is full of hits. Cards like Shatterstorm are undoubtedly great against Lantern, but even if you can keep one through discard and draw it through mill you can be locked out of the mana to cast it — or the tools to win the game afterwards. When going to war with Lantern, you need a deep bench.

Why does this advice all feel dated now? Why hasn’t Modern’s greatest menace returned even though its main predator was banned?

One answer is that previously close matchups became much harder with new printings. Azorius Control and Jeskai Control were never easy, and the trifecta of Search for Azcanta; Jace, the Mind Sculptor; and Teferi, Hero of Dominaria gives Modern control decks a full roster of threats that trump Lantern’s basic gameplan. The outlook is even more grim after sideboarding as dead removal spells are traded in for more countermagic, disruptive pressure like Vendilion Clique or Spell Queller, and high-impact answers like Engineered Explosives or Stony Silence.

Meanwhile, Thoughtseize and Tarmogoyf aficionados have returned to their roots and loaded up their Golgari decks with Tireless Tracker, a continuous card advantage engine with no convenient answer to search for, as well as Assassin’s Trophy and Field of Ruin. Dredge has shambled back to the top thanks to Creeping Chill, a card that’s messed up against most things but laughably so against Codex Shredder.

None of these cards spells doom by itself, but they all make existing issues worse and create new ones, either by increasing the density of relevant cards in the deck, giving you new ways to find those cards, or shifting the game onto a new axis for which even the broadest answers in Lantern are poorly suited.

We can expect a similar trajectory for Whir Prison. The natural ebb and flow of the metagame will mean that the format is more hostile for Whir Prison at times, even if people don’t explicitly target it — which they certainly should after its recent results. But how to do that?

Let’s look at Whir Prison through the lens we used for Lantern.

While Lantern left no zone untouched, Whir is all-in on playing to the battlefield. Instead of discarding your first answer for Ensnaring Bridge and stopping you from drawing a second, Whir powers through those answers: it already has more Bridges than most opponents have Shatter effects, but it also has its namesake card (and, in the four-color list, Ancient Stirrings) to find it and a pack of Welding Jars and Spellskites to keep it sturdy. Modern is such a broad format that sideboard space is stretched thin and players look for cards that can serve multiple roles: weaker at any one thing, but good at more things. The result is that you see fewer Shattering Sprees and more Abrades and Rakdos Charms which, as one-for-one answers, simply don’t do enough to reverse that basic math. Where Lantern demands addition, Whir demands multiplication.

If Lantern looks bizarrely aggressive from the right angle, Whir Prison is definitively passive. Without discard or the library lock to snipe crucial cards in advance, Whir Prison is forced to care about the text on those cards and trust that its toolbox has the right blunt instrument for the job. No possible lock piece can cover as many bases as a simple Thoughtseize. A big part of the four-color list’s success is that Chalice of the Void is closer to a universal answer in Modern than it ever has been: even when it isn’t shutting down a third of the opponent’s deck, it can preemptively block a key card or ward off their one answer to your actual hate card.

When they don’t care about Bridge, or Chalice, or any of your other tools, you have not just a problem but a fundamental problem. If the Cryptic Command matchups were challenging for Lantern, they’re a nightmare for Whir; very few of your cards do anything, and those can be banished back to your hand when the time comes. Even in its worst matchups, Lantern can nullify the first wave of threats and cut off access to the second; without those proactive elements, Whir can’t pivot into a new plan as easily. The Tezzeret and Sai sideboard switcheroo can be effective but shouldn’t surprise anyone who does their homework.

This reactive quality of the Whir deck completely changes the endgame dynamic in the matchup: the game will go on for a dozen or more turns, and you can draw as many cards as you want (via as many Chromatic Spheres as you want), but the game is effectively over once the pieces come together. This gives you the freedom to craft your own endgame; if that endgame seizes control of the narrative, it’s hard for them to take it back. Putting one Shatterstorm in your sideboard barely affects your winrate against Lantern but increases your winrate against Whir more than any other change would against any other deck.

Sideboarding in Modern often involves sideboarding in powerful hosers against fast linear decks and hoping to draw them before you get run over, and you need several copies of that effect to do this reliably (part of why Izzet Phoenix continues to perch on top of the format is that it sees so many cards per game that its sideboard does more with less: its copies of Blood Moon are much more punctual than Affinity’s). Against Whir, you know you will have the time to find and resolve your superweapon, even if you can only afford one. If you aren’t sure how to round out your sideboard and your Whir matchup is shaky, that fifteenth card can do a lot of work. Just make sure it does what you hired it to do; a Creeping Corrosion that smashes a Welding Jar but leaves you stuck on a Bridge is a failure.

You could use this comparison to argue that Whir Prison is indeed worse than Lantern (even if not strictly worse), but that misses the point. Whir is doing its own thing and that happens to be a better fit for Modern at this snapshot in time. When the format shifts again, that fact may change; when it does, being aware of these conceptual differences lets you notice that and stay ahead of the game.

The list I played in the Classic occupies a middle ground. If Lantern is aggro-esque and traditional Whir is pseudo-control, Dimir Whir can feel like an odd constellation of combos. Your goal is to identify some mix of cards that beats your opponent and pursue that with a singular focus: sometimes that’s an obvious combo like Thopter Foundry and Sword of the Meek, but often it’s a hate card or Whir plus the mana to cast it, or Ensnaring Bridge plus nothingness.

The polarized nature of most cards against most decks makes sideboarding both easier and harder. A lot of it is so simple that just writing it feels insulting — yes, sideboard out Grafdigger’s Cage against Tron! — but those final, marginal choices demand a deep understanding of the matchup. Perhaps Pithing Needle has no obvious victims against their maindeck but their long-term post-sideboard plan hinges on activating a card that you haven’t seen yet; you need to anticipate that and, ideally, work out what it is.

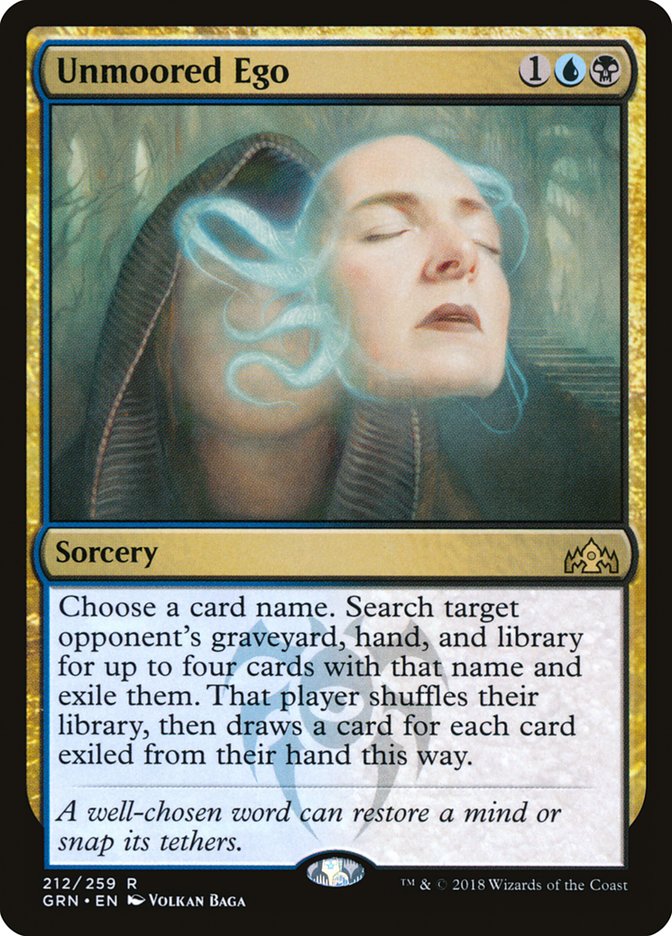

In general, Spellskite comes in against most decks as they sideboard in ways to interact with your key cards. Sai is worth it whenever a wall of Thopters can buy good time or win the game by itself. Tezzeret gives you a needed win condition against Stony Silence or Rest in Peace, a fast clock against combo (often where Thopter-Sword is weak), and a resilient threat against midrange or control. Unmoored Ego should only come in if removing one card lobotomizes the opposing deck or disables their counterplay (I’m toying with bringing in a copy or two to hit Shatterstorm against Izzet Phoenix). If there too many dead artifacts to take out, leave the cheap ones that can help for improvise and metalcraft.

Thopter-Sword is the headline act for this deck. Against any aggressive deck, Foundry itself buys a lot of time to assemble a lock, which is much easier when finding Sword also completes that task. It also gives you a strong, cohesive plan against control: Foundry is cheap enough to come down before their unconditional answers, at which point the threat of Sword of the Meek hangs over the game. Whir for Foundry is now an instant-speed threat that they must respect, making it highly dangerous to ever tap out. In general, any deck that plays to the battlefield is easily buried under a swarm of Thopters if you have enough time. Against decks that don’t care about the combo, it still provides a clock that the deck is sorely lacking otherwise and that can steal games.

The black sideboard cards are a big draw to Dimir. Unmoored Ego is the perfect effect to rein in the combo decks that won’t show up at the courthouse. Collective Brutality is a jack of all trades (and your ace in the hole against Burn) that unclogs your hand for Ensnaring Bridge or clears the way for your haymaker. Battle at the Bridge is your ideal removal spell, giving you a solid life buffer against Burn or Phoenix, scaling well as the game goes long, and swatting away any Spell Quellers still flapping around the fringes of Modern.

This all comes at a cost. Ancient Stirrings adds a ridiculous amount of consistency to any deck that supports it and the green list gets to play more copies of various lock pieces with the space taken up by Thopter-Sword, which bloats the mana curve and makes it harder to empty your hand for Bridge. It’s hard to argue against a card that many wish had been banned ages ago, but I was happy to make that case this weekend.

Dimir Whir might not be better than regular Whir Prison next week — it might not be good at all next week! — but this should help you to identify when and why it is. Unmoor your ego, unlearn any wrong lessons, and unlock the full potential of one of Modern’s strongest strategies.