How do you go from merely good to great?

Some say it takes 10,000 hours of practice, and for games like Magic, some think it might have something to do with innate talent. Maybe some people “get it” while others don’t.

I think that’s bullshit.

The difference between being a good player or a great player is often a thin line. Instead of one big secret, it’s often just a bunch of little things that separate those two groups. This article isn’t the most extensive list, but it does contain some of the more common pitfalls good players face once they plateau.

Anatomy of a Mistake

A mistake is defined as “an action of judgment that is misguided or wrong.”

What constitutes a mistake is often a topic of debate. There are both judgment calls and actual misplays, but the actual value of what a mistake is can vary. Did it cost you a game? Could it have potentially cost you a game? Was it completely irrelevant, yet still something to avoid in the future lest you develop bad habits?

If you bluff attack your 1/1 into their Mavren Fein, Dusk Apostle and they block, is it a mistake? If you decide yes, then it should still be a mistake even if they take the damage. You can’t always predict when your opponent is going to make that block, but making a calculated risk can’t only be a mistake when they call.

If you’re at nine and your opponent is at six, should you use a Lightning Bolt on their attacking Ball Lightning? What if another Lightning Bolt ends up being on top of your library? Does it mean you should have waited?

These are judgment calls that can be argued either way but will ultimately come down to math. Sometimes the math isn’t obvious, so you have to go off intuition.

Sometimes your intuition will be wrong. You have to be okay with that.

Sometimes I make suboptimal plays while executing my winning line, but that shouldn’t count as a mistake. Any winning line is good enough, even if it’s not quite as good as another would have been. That said, if one line gives your opponent an extra draw step or a chance to win, it should definitely be avoided.

Additionally, just because you make mistakes doesn’t mean you should get down on yourself. A game of Magic isn’t determined by who made the most mistakes. You shouldn’t feel bad about winning despite making a mistake and you shouldn’t let it determine how resolved you are during a tournament. There should be no shame or embarrassment involved in making a mistake.

The fact of the matter is that very few games will be played perfectly. If you can’t find mistakes within your game, you aren’t looking hard enough. Those mistakes definitely exist, even if you can’t see them, and you shouldn’t beat yourself up over them when you do see them. Acknowledge a mistake, make sure you don’t make the same mistake again, and then move on.

How much does a mistake really matter? How much should it bother you? How should you compose yourself after it happens? The secret is that what is and isn’t a mistake doesn’t ultimately matter. Mistakes are going to happen, so it’s pointless to beat yourself up over it. If it causes you to tilt and make even more mistakes, what’s the point?

Is it useful to define what is and isn’t a mistake, especially during a match? It might not even be useful to define it during a tournament. Games have all sorts of actionable data points and even more that aren’t. Additionally, there are actionable data points that don’t correspond to specific plays and whether they were mistakes at all, such as the flow of the game. That should influence what your vision for the game is.

Instead of viewing those data points as mistakes (and therefore negative), view them as a learning experience (and therefore something positive). At the end of the day, if you learned something, it’s valuable.

Entitlement is also a risk, no matter what your skill level. One of the things I’ve had to re-learn several times over the course of my career is that I don’t deserve anything. No matter the tournament or skill level of my opponent, I need to work for every point of damage and every game win.

My ceiling is high but my floor is pretty damn low. I can’t remember a single tournament where I just copied a deck and either didn’t know the format well or hadn’t practiced. There have definitely been tournaments where I’ve done well and also made mistakes.

I’m good with flashes of great. I’m also fine with where I am as long as I’m also trying to improve.

How Much Credit to Give Your Opponents

Figuring out how much credit to give your opponents is one of the toughest things in Magic. There’s typically a stark difference in play skill and experience at the various levels of competitive Magic. How you play against each of those players should vary depending on what sorts of plays you think you can get away with.

Does your opponent know how to bluff? Are they capable of bluffing you? If they represent a trick, does it mean they have it? If they had a great opportunity to use a Lightning Bolt but didn’t, does it mean they don’t have it? Are they going to play the matchup or sideboard how you’d expect? It’s difficult to get those answers.

You can make some generalizations on based on your opponent’s pre-game banter, their shuffling technique, and whether or not they use dice to track life totals. It’s never perfect, though, and you’re better off getting a real impression from how your opponent handles themselves in-game. Judging someone solely based on their shuffling technique will frequently let you down.

Once I played against a highly regarded professional and lost because they kept a bad hand. In the Delver mirror, I played around a Divine Offering because I couldn’t fathom a world in which they kept a hand that was as bad as theirs without overvaluing a Diving Offering. I didn’t jam my Sword of War and Peace and would have won the game if I did. As it turned out, his hand was just bad.

Because of who it was, I played differently from how I should have, and it cost me the match.

Your opponents will often do things that you wouldn’t do yourself. I constantly see opponents keep hands I wouldn’t and sideboard in ways that confuse me. They probably even have cards in their sideboard that I’m not expecting because they don’t make much sense to me.

Rather than say “my Temur Energy opponent won’t have Glorybringer against my Ramunap Red deck post-sideboard,” instead play around it if you can afford to. Similarly, I thought it was fairly normal for Temur Energy to sideboard out Glorybringer against Ramunap Red, but many of my Hazoret-playing opponents at Grand Prix Portland brought in as many as three Chandra’s Defeats against me. If I sideboarded how they “should” expect, I would have only had Whirler Virtuosos in my deck as targets!

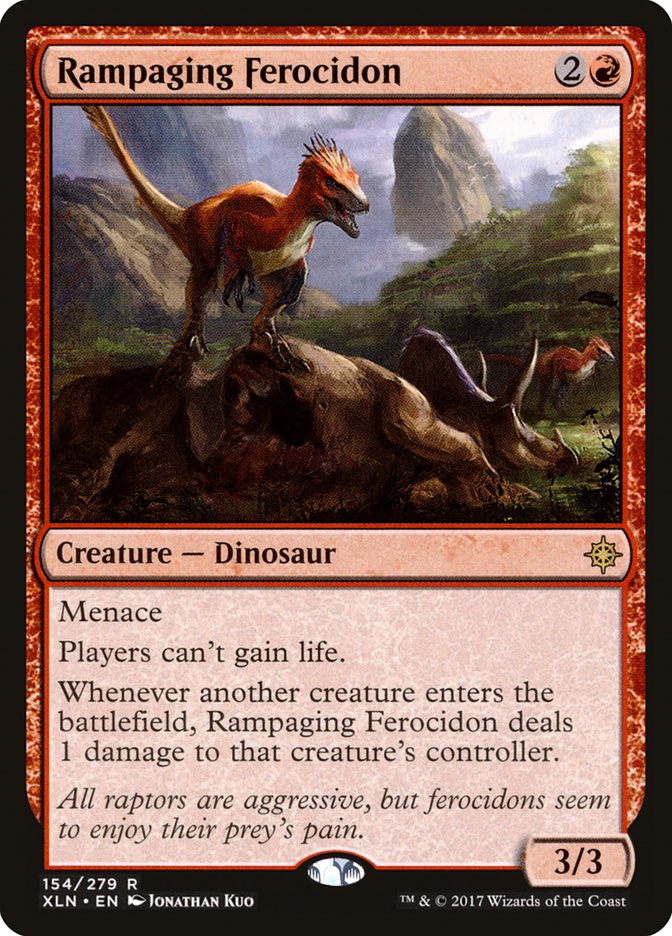

Glorybringer tends to be too slow in the Ramunap Red matchup. If you have to exert it, you will probably lose on the subsequent turns before you can race them. However, the red decks have been slowing down as of late, and having removal for Rampaging Ferocidon is of the utmost importance. They have enough threatening cards on the ground that you need a big flier to race. Hazoret the Fervent can hold the ground long enough for them to burn you out also.

Knowing that Chandra’s Defeats would be raining down upon me, I would have altered my Temur Energy deck to have a similar plan as my Pro Tour Ixalan Temur deck with Skysovereign, Consul Flagships and Confiscation Coups as my five-drops. Chandra’s Defeat would have been embarrassing against me. Instead, I walked into their “trap” repeatedly.

It might seem like a situation where I was punished by my opponent’s “mistakes,” but in reality it was something that shouldn’t be surprising for them to do and I could have played around it. If it’s free, you should absolutely play around whatever you can, even if it’s nonsensical. Just be aware that you could be giving them more time to draw into something else nonsensical. At one point, I’m sure River’s Rebuke took plenty of people by surprise.

People are allowed to do anything they want to. In fact, I take full advantage of it and try to prey on what I think my opponents will or won’t suspect.

Playing with Daze in Legacy is a delight. I will frequently play small numbers of Daze in decks where people wouldn’t normally expect it, such as Grixis Control or U/W Miracles. Additionally, I will usually keep in some copies, even on the draw, in matchups where I’m “supposed” to sideboard it out.

Is doing those things “right?” Absolutely not, but it gives me an advantage if my opponent actively chooses to not play around Daze and walks right into it. In decks with Force of Will and Brainstorm, finding a way to get a use out of it is pretty easy. It’s not the highest-EV decision overall, but it’s one of those things that will allow me to win games I wouldn’t have any business winning.

Focus on What Matters

There seems to be an air of mystique around professionals in any industry. They probably do things that are crazy and unique; otherwise, how could they possibly rise to the top? Putting those people and their skills on a pedestal is why you’re nervous to meet your heroes and so eager to watch them play and learn from them.

It’s often disappointing when you realize they aren’t that different from you.

One of the easiest ways to get distracted from a quest to be great is by focusing on things that aren’t relevant. Instead of honing in on improvement, they might single out skills that are tangential to Magic but ultimately have very little bearing on tournament success if their fundamentals aren’t up to snuff.

For example, using various bush league tactics like learning how to trick people using the rules, trying to distract your opponent in order to get them to miss a trigger, or coercing their opponents into conceding to them are exactly the types of things you shouldn’t be using your brain power on. There are more important matters on hand.

If you try to trick your opponent but miss a trigger and two points of damage, it’s probably not worth it. Maybe you can do both, but I firmly believe that’s only something you should work on once you’re already a great player.

Being Creative

Having the ability to be creative in-game is both a blessing and a curse.

There was a time when Josh Cho used to use his creative powers an unhealthy amount. Maybe Magic was too boring for him, so he tried to set up convoluted battlefield states where he could blow his opponents out. Since then, he’s tightened up a bunch and only gets creative when he knows it will work or when there is no other option.

Again, thinking the secret to being successful is doing something special isn’t correct. There are times when you can do something creative and win as a result of it, but those times are few and far between. In my career, it’s happened fewer than ten times, so maybe once every two years. And that’s for me, who plays more Magic tournaments than 99% of the player base.

Being on the lookout for those spots can be important, as they’ll allow you to win a game you couldn’t win otherwise. But again, you can’t waste that brain power attempting to fabricate those situations.

***

I hesitate to call myself a great player, but either way, there isn’t a closely guarded secret to being one. It’s less about knowing the things that it takes to be great and more about the things you have to avoid. Becoming great is just as much about dropping your bad habits as it is about sharpening your skills, whether in deckbuilding, sideboarding, drafting, or just playing out the games.

It’s a long road, and possibly one that never ends in Magic. Maybe that’s why we love it so much.