I’m going to start part two of this series off with a bit of a tangent to speak on suspension of disbelief. I’m also going to start out with a story that’s based on real events. If you want to get right into prison, skip to the heading “Wake Up Kid! You’re in Prison Now.”

Suspension of Disbelief

Imagine if you will a lavish suburban D.C. apartment. Located on the top floor of the cushiest building in the metro area, the double-wooden doors are deep crimson, and their brushed nickel handles open to a space so overwhelming that it has a name. Donald Trump has Mar-a-lago, Eddie Murphy has Bubble Hill, and whoever lives here is the proud and mysterious owner of Heavenlumps.

When the doors open to Heavenlumps, you see only a single consistency from wall-to-wall: decadence. You remove your shoes, as is clearly the tradition here, and your worn out Converse All-Stars are out of place next to the mint-condition Air Jordan I’s and seemingly gold-plated Air Max’s. There are Reebok Classics in colors that must be custom and a pair of Adidas shelltoes that appear to be signed by all the members of RUN DMC. The walls are lined with the furs of exotic and very probably endangered animals; a jet black baby grand piano plays “hit me with a hot note, and watch me bounce” and other jazz standards. The floors are hardwood stamped with a seal on each polished plank that lets you know each one is made of South American rainforest mahogany. The couches are some alien leather (shark, perhaps?) and each armrest is carved with the head of not lions, but cartoonish salmon. The air smells of pineapples and sizzling garlic, passion fruit, and bizarre game animals. The kitchen feels alive at a glance—stainless steel appliances and cabinets reflect your movements back at you. You run and sock-slide across the marble kitchen-floors and fall just shy of the liquor cabinet, laughing at the pain.

The spirits are locked behind some kind of fingerprint-recognition device, but before fiddling with it, you hear the deep moan of a creature in the throes of total ecstasy. Your eyes quickly dart to the back hallway, just past the elevator, where a figure is staring at you stoically. As he emerges from the shadows, the towering man looms over you with the silent confidence of a man who has killed before. His tuxedo is pristine, save for a few brown flecks on his bowtie. He has the skin of a man who spends far too much time in the sun, and, as he offers you a gloved hand, you feel the calluses beneath his silken mitt.

“Welcome to Heavenlumps,” he booms, pulling you up off of the floor. “The master will see you in the bathroom now.”

“The master?” you offer. “But who are you?”

“I am Vandelay; I have been the manservant and bodyguard to Master Timothy since his birth. I come from a very long line of gentlemen’s gentlemen.” Vandelay turns on his heel and you follow him to the bathroom.*

The doors to the bathroom open inward, and the delightful smells present within the other parts of Heavenlumps are overwhelmed by the scent of rich, dark cocoa. You scan the bathroom, which is bright white everywhere, wondering how much of this is polished ivory? when a stirring “glump-wump” distracts your thoughts.

You see an in-ground bathtub the size of a Jacuzzi, flanked on all sides by what looks like melted chocolate. The tub itself is filled with the substance, which bubbles infrequently. Is this a huge double boiler? Is Timothy a modern-day Willy Wonka? Slowly the chocolate comes to life, and from out of it something which looks vaguely human and vaguely like Admiral Akbar emerges. Could this be? A creature which can breathe under molten chocolate?

“Do not be alarmed,” the creature says, licking his face as far out as his tongue will stretch. “I know you have a menagerie of questions running through your head right now: Who am I? How much of this is ivory? Am I Willy Wonka? The answers to your questions, my friend:

“I am Timothy Pskowski, master of Heavenlumps.

“All of it.

“Perhaps.**

“Now I would ask you to disrobe and join me in my pudding bath, so that we may discuss my purchase of the Picasso you’ve stolen.”***

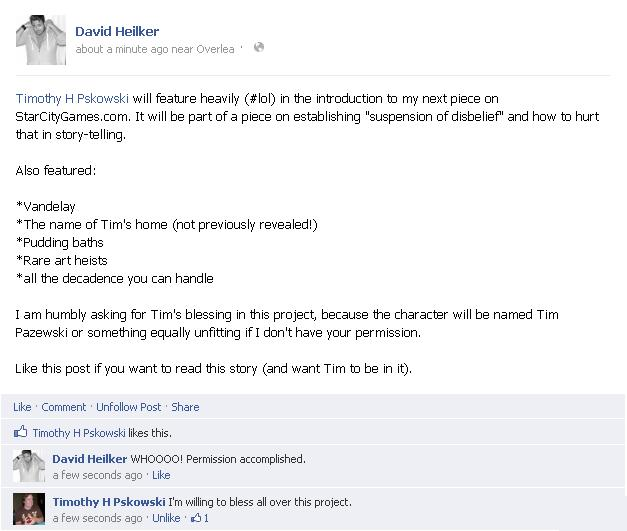

This is proof that I have Tim’s permission to use his likeness in the above tale, although, as I understand it, the truth is a perfect defense to libel:

Great, now that that’s outta the way, I want you to go back and reread this (mostly true) story, but I want you to add the following to the noted parts:

* He turns to you and says “I suppose you didn’t realize I could fly!” and as you look down at his feet, you are startled to notice his polished shoes are hovering above the ground. He’s not. touching. the. ground.

** You also are probably concerned by how Vandelay can fly too: He’s a vampire. His family hasn’t been with us for generations — HE HAS!

*** …stolen, and our upcoming adventure at the National Museum of Egypt!”

Something feels wrong, doesn’t it? It’s the same feeling that many of you claim to have gotten from Cavern of Souls. It feels “tacked on.” There’s almost a response of the uncanny to these types of objects when presented to people for observation. This is what that means (from Wikipedia):

The Uncanny (Ger. Das Unheimliche — “the opposite of what is familiar”) is a Freudian concept of an instance where something can be familiar yet foreign at the same time, resulting in a feeling of it being uncomfortably strange or uncomfortably familiar. Jar Jar Binks was uncanny and George Lucas eats children, and he killed President Lincoln.

Some of that may need to be edited, but you get the point, hopefully. When something is out of place in an environment that has been made familiar, we’re uncomfortable with it. This is why when you come home, and something is out of place, you get uneasy. The funny thing is, I could probably have got those details into the original story and had it be believable, but as an afterthought it doesn’t make any sense—you already have a thought structure about this story. This is what suspension of disbelief is about, on the basest level. Suspension of disbelief is when you set up the rules for how your story is going to work versus the real world. It’s got to happen early enough in the story to allow the audience to immerse themselves in it. The thing is, you only get like, one shot to do this. Now sure, there are exceptions to the rules, but if I start out a story about zombies, and this Zombie Infestation is the only remarkable thing about the story, and then 3/4 of the way through I say, “and then a werewolf popped out and chased us,” you’re gonna be all “Wtf?“

The reason I’ve begun this week’s piece about the suspension of disbelief and how it works is because behind each Magic set, there’s a narrative. It might not have been as fleshed out back in the day, but through retconning it definitely is now. We’re telling a story, and while there may be something that happens in the third act that’s groundbreaking (see also: Eldrazi, the return of Avacyn), that doesn’t mean there wasn’t allusion to it, or build-up in the other two acts. People believe the story in the context of the story, because we’re not breaking any rules after we’ve set them.

More specifically though, I bring this up because Ciesta didn’t win (it was my favorite) and because the following statement was made in the comments last week. This is the Ciesta Story, for reference:

The world of Ciesta has been, until recently, a plane of extreme quiet. Almost all of its denizens share a continuing collective unconsciousness as they’re all asleep. While the people and creatures of Ciesta sleep, their dreams are used to fuel the magic of the somnamancers, a guild of mages who draw inspiration from the dreams of living things.

Unfortunately for the somnamancers, while they practice some of the most powerful magic in the multiverse, they are cursed to never sleep themselves. Something has changed, though. Generally on Ciesta, nightmares are relegated to dreams-within-dreams and are not a shared experience, but a host of nightmares has recently invaded the world.

This is not entirely fleshed out, but one reader took some issues with the story:

Let’s speak to some of Professor Blake’s problems with Ciesta, just to prove that we could do this while suspension of disbelief remains firmly intact.

Let’s continue the story of Ciesta, from where we left off:

Before our audience arrives on Ciesta (the true name of the plane is unknown, the “dream world” is Ciesta), a young man awakens from Ciesta and into what the somnamancers call “The Waking World.” He is jarred to wake because he is, unbeknownst to himself, a powerful planeswalker, and his powers manifested when his dreams started coming to life (within Ciesta). He willed himself to wake into the Waking World.

When he discovered that everyone he had ever loved was part of an experiment, he consulted the somnamancers to learn how to safely wake them up. They explain to him that there is no way to wake them safely. They are ‘locked’ in the dream unless the somnamancers all break the spell holding them in (which they are magically unable to do without there being a threat to all of the inhabitants of Ciesta). They invite him to fall back into Ciesta, which he flatly refuses. The young planeswalker decides the best way to get the people he loves into the real world is to introduce a threat to Ciesta, so he feeds nightmares into the world.

Unfortunately, the nightmares he unleashes into Ciesta quickly consume the minds of many of those still dreaming and terrorize Ciesta. To the young planeswalker’s horror, his younger sister is killed.

Ciesta focuses on the conflict of the nightmare war occurring in Ciesta itself, as well as the struggle between the young planeswalker and the somnamancers in the waking world.

NIGHTMARE WAR? Can you imagine thatas a set title?! Who wouldn’t be excited? So how do we address Mr. Blake’s questions?

Well, the somnamancers are always awake. They are not only harvesting from the sleepers’ dreams, but they’re also keeping them alive. Each color would have a specific category of somnamancer to take care of a specific task to keep the world running:

White Somnamancers

These are the warrior-minded. They operate dream-soldiers in between the two realities to ensure that those who may discover the illusion are subdued.

Blue Somnamancers

These sorcerers work in the waking world to keep the illusion of Ciesta continuous. When one slacks or neglects his post, psychic phenomena occur.

Black Somnamancers

These wizards regulate sleep within Ciesta. Normally, falling asleep in Ciesta would cause one to awaken. These sorcerers are charged with keeping that from happening. They are called Sandmen.

Red Somnamancers

These shamans are charged with regulating the flow of mana from Ciesta into the waking world. They work in pairs, and are called Channelers. They harvest mana from the dream(s) themselves.

Green Somnamancers

These mages are assigned to the task of using the mana generated by Ciesta to fill it with wildlife, and to keep the Waking World and all of its awakened and asleep citizens alive and sustained.

Wrapping up the Nap

To speak to Blake’s concern about snowstorms, that, I feel is the easiest factor to dismiss with a simple explanation: Ciesta/The Waking World is an artificial plane, created by a planeswalker who is running a particularly exhaustive (#puncheck) sleep study. There is no natural weather. As long as we establish this aspect of the plane early, we’re not dealing with a lot of trouble in the “fantasy-believability” department. See also: The Matrix. I’m not saying there aren’t unanswered questions with that series, just that as long as the unanswered questions aren’t overwhelming, a story can be enjoyable.

Wake Up Kid! You’re in Prison Now.

ANNOUNCING AZATHU

(We need a better logo! Help! Email to davidj DOT heilker AT gmail DOT com )

Tagline: Getting in is Easy—Getting out is Deadly. (probably need a new one of these, too!)

Set Name: Azathu

Codename: “Ready”

Three-letter Abbreviation: AZA

Number of Cards: 249

Expansion Symbol

So, Azathu, for reference:

95% of Azathu is undeveloped wilderness. But in the expansive wild stands what appears to be a massive obelisk. On all sides, this towering monument is guarded by seemingly ornamental stone sentries and protected by some of the most powerful magic ever practiced. Truly, this tower is a prison for the vilest criminals in the multiverse. Power is only measured two ways, brute force and charisma, and if you’re short on either, you’ll find yourself at the bottom of the totem pole… or six feet under it.

But one of the inmates has recently discovered he’s more powerful than his captors initially thought. During a brutal beating that should’ve ended his life, his spark ignited, and he discovered he was a planeswalker. He’s determined to break free of Azathu and take some of his friends from the inside with him.

So that’s the story, or no it’s not. That’s a basic concept t̶h̶a̶t̶ ̶t̶h̶e̶y̶ ̶w̶o̶u̶l̶d̶ that we will be fleshing out into a rich world with dynamic characters and compelling events. What we have to do first is plot the story. We’re going to design with a block in mind (although we’re only planning to design the first set) so let’s hammer out what should be going on in each of the sets:

Set 1: AZATHU (the first set is usually named after the plane, by modern conventions). After generations of peace outside Azathu, in The Tower (the name for the prison itself) there have been myriad escape attempts, but none ever successful. The wards and seals placed on the tower prevent escape through anything but the most powerful magic. The unfortunate thing is, some people have been able to break into The Tower before, hoping to then assist an old friend or business partner to break out—this has never been a successful venture.

The wards on The Tower don’t prevent the spellcasters within from using mana, and the mana in the Azathu wilderness is rich and potent. This means that the most powerful mages on the outside are often the most powerful within the confines of the tower.

Power is Survival

The Tower seems to be unmonitored. There are small automatons which roam The Tower and take care of housekeeping, cooking, and other minor matters, but they are too small to ever be expected to subdue an inmate, or suppress an uprising. Inmates come and go from the yard to their cells as they please. The cells allow for the inmate assigned to enter and leave but prevent people who are not the assigned inmate from entering. There is no one in The Tower to assign cells, but when someone is condemned to exile on Azathu, they arrive in their quarters.

Those who are unbelievably strong, or crafty, or intellectual are able to rise to the top of the inmate society, with various factions being led by individuals who have won other inmates to their cause. Knowledge is power in The Tower, but so is strength. It’s easy enough to illustrate power, but how do we illustrate craftiness or intellectualism? Incoming mechanic.

Submitted for your approval: Clout

Clout X ( CARDNAME has protection from spells with converted mana cost X or less, and from creatures with power X or less.)

Some examples:

Now these are the first crack at some cards, with the first crack at a mechanic. I enjoy the way these make the creature feel more powerful even at lower power or with very traditional abilities. It’s a new kind of evasion that will require we design around it. If, for example, Clout was to be prolific on the creatures in this set, would this be a good enough removal spell?

Within the constraints of the set, yes, but is this too good to print? Very likely also yes.

What about this?

Clout is an interesting mechanic because it feels like the influence one might gain within a prison and it opens up some interesting design space, but we have to understand how it limits us. If it proliferates too much throughout the cards in the set, we just have a bunch of virtually-shroud creatures having fun together in the prison yard, and that sounds like a terrible Limited format.

What cool cards would you want to see us try with Clout? What other design-constraints can you see becoming real because of it?

It becomes pretty clear pretty quickly that this set will care about a creature’s power and toughness and/or mana cost. How do we convey the former (with Clout demonstrating the latter)?

Can we look to Naya for guidance?

I Thought You Were Dead!

So we have this guy, and for now we’ll call him Sander Feydun (an anagram for a famous prisoner from cinema). Sander was an ecological alchemist (biologist) as a young man. He studied magical creatures on his home plane of Nameneedia. He thought he found a cure for a blight which was threatening the trees of his home plane, but unfortunately for Sander, while the treatment stopped the spread of the blight, it did so by petrifying every tree on his home plane. A tribunal was held, and he was found guilty of crimes against nature and arboricide (is there a word for the eradication of a species of plants?). Upon his arrival at The Tower, the inmates assess him to be scrawny and sent by some terrible mistake.

But pity and sympathy are rare emotions on Azathu. Sander immediately distinguishes himself as a loner, but also as a powerful alchemist, and one who has enough command of sorcery to warrant being left to himself.

When one of the leaders of a more dangerous faction in the Tower, The Felmir, take interest in Sander’s chemistry proficiency with laughable ineptness, Sander insults his arrogance, and word spreads through The Tower faster than wildfire that Sander doesn’t pay the appropriate respect to the ganglord. This causes considerable embarrassment to the leader of The Felmir, and he puts a hit on the alchemist to demonstrate that he has no intention of taking slights lightly.

Sander is cornered by a group of taskmages associated with The Felmir, and beaten to death. Hours later, he awakens confused and in his cell. He is in pain, but he’s alive, and he’s not much worse for wear. A power in him has been unlocked, and his next move is getting out of this place.

The remainder of Azathu’s first set storyline revolves around Sander’s discovery of his abilities as a planeswalker, forging the appropriate alliances, and the climax, of course, is his escape from The Tower.

Major Players

There are some characters we need to address within the set, either through flavor text, or actual cards.

The first and foremost of these would be Sander, who would appear as a planeswalker. Other characters to consider:

Various prison gangs and their ganglords.

The Tribunal: the (planeswalkers?) wizards who hold a council to determine whether someone from any given plane is too much of a threat to remain among its people. Would they be interplanar? Or would they just arrive at a plane to hold their crucible?

The automatons all have different functions within The Tower; how would we represent them on cards?

What races do we want to consider for within The Tower? I think with the exception of those that would be ungovernable (Zombies, for example) we would want a number of species to be well-represented.

It will be important to stitch in some creatures and environments outside of The Tower, in order to establish an expectation of environment for Sander in the second set of the block.

Meanwhile, on Earth

This has gone on pretty long, so I’ll wrap it up for this week with a couple questions:

Excluding those who were prominently killed (Crovax, for example) and those who are planeswalkers, who can we bring back as a role-player or supporting character? Think villains from Magic’s past.

What do you think of Clout? How can it be improved? What kind of problems do you see rising from such a mechanic?

What other kinds of mechanics do you think work thematically with a prison world? (While I will continue to brainstorm these, I would love your input—if you comment with a cool mechanic that makes sense thematically, maybe we’ll use it in Azathu!)

One of the mechanics I was working on was called Breakout, and it was templated like this:

Breakout COST (When you are searching your library, you may PAY COST, if you do, put CARDNAME onto the stack).

What I didn’t like about Breakout was having it be an ability of multiple cards in a set where the remarkable event is a character breaking out of an “inescapable” prison (a feat that has never before been accomplished). I thought it might be appropriate to make it an ability of the card which would feature Sander, but the additional design hazards here are myriad: we would have to incorporate a lot of “search your library” effects to make it a worthwhile mechanic, and those generally lead to shuffle effects, and that’s generally something we don’t want on more than a limited number of tournament playable cards in any given environment. Just some food for thought when you’re thinking of mechanics yourself—there are more questions than “What makes sense in a ______-themed world?” I suppose this is the part where top-down design starts getting more difficult.

Bonus Section

I was discussing why Spider-Man 3 was terrible with the girl I’m dating, and it kinda came full circle to the whole suspension of disbelief section up top.

When Sam Raimi took on the Spider-Man series, a lot of fans huffed and puffed about Spider-Man being able to web-sling without “web-shooters.” Raimi said something to the effect of (paraphrased):

Why would a man with spider-powers be unable to emulate their most remarkable ability?

He would go on to discuss that while it’s believable that Peter Parker (Spider-Man’s secret identity) could be granted these amazing powers, it’s not believable that he also was enough of a genius to create web-shooters and fluid.

Pretty amazing that he would then ask us two short films later to believe that an alien symbiote fell randomly from the sky on a meteorite and jumped onto Peter Parker’s Vespa because it heard there was a party later.

That’s where you lost me, Sam.

Anyway, I was really pumped to show everybody the mechanics I designed for Ciesta, because I thought they were fun, flavorful, and elegant. I’ll leave you with those:

Â

(I’ve kinda got this thing with Goblin Guide)

Let me know what you think of Ciesta’s mechanics!

That’s it for this week. Check out my band (like us if you like us)!

Best Wishes,

Dave Rockstar