Modern and Standard are in vastly different places right now.

Modern is as diverse as any format I have ever seen, with twenty or more decks showing up on any given weekend and nothing taking up more than about ten percent of the format.

Standard, however, is dominated by two cards: Collected Company and Emrakul, the Promised End. Bant Company is consistently 30% of the field at tournaments and the only reason there aren’t comparable numbers for Emrakul, the Promised End is that it appears in so many different, but all too similar decks. Jund, Temur, and B/G are all decks that have been built to cast Emrakul, the Promised End as consistently as possible.

The sum impact of those two cards on the format is absolutely enormous, to the point where the only thing saving them from serious ban discussion is how close we are to the release of Kaladesh.

Diversity is the most cited metric for format health, and yet my conversations with players have typically shown that they strongly dislike Modern while approving of Standard in spite of its shortcomings.

The reason for this is fairly simple: it’s the gameplay.

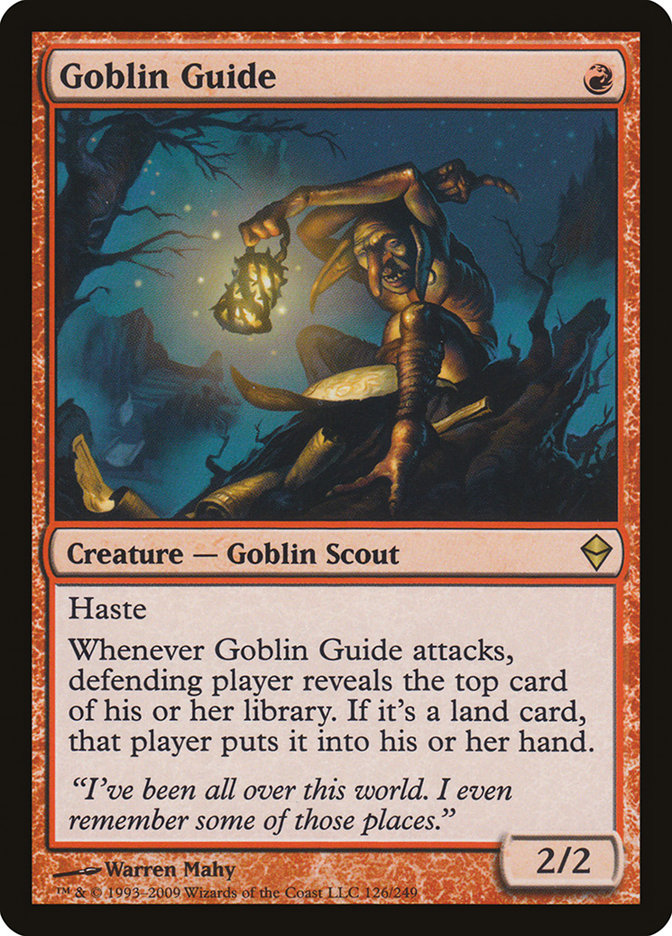

Modern may have plenty of distinct archetypes, but by far the largest portion of them are trying to limit interaction as much as possible and set up a quick kill. This was no more evident than in the closing game of #GPIndy last weekend, where Brandon Burton ended the game on turn 3 with a flurry of Lightning Bolts and Lava Spikes to follow up his turn 1 Goblin Guide. The lethal Lightning Bolts were cast in response to his opponent’s Primeval Titan, a card notorious for years for its penchant to end games in a hurry, even leading to the ban of Summer Bloom earlier this year.

The emotions surrounding Burton’s victory, while representative of the best that our community is capable of, also served to mask the irony of the moment: Modern is supposed to be a turn 4 format, and the final game of a Modern GP ended on turn 3.

Contrast this with Standard, whose decks are all more than happy to play very long games. Bant Company may be the aggro deck of the format, but between Tireless Tracker, Duskwatch Recruiter, and Nissa, Vastwood Seer, it can grind with the best of them.

It’s not uncommon for games of Standard to go past turn 10 with both players’ hands still flush with cards. Even the premier game-ending card in the format, Emrakul, the Promised End, may need to be recurred once or twice with Grapple with the Past before its victim admits defeat.

Regardless of other factors, these long games generate more tense moments and drama than their shorter Modern counterparts. Most of the time both players will leave feeling like they got to play a fair game of Magic and had a good chance to win. Moreover, long games will always produce moments that you can reflect upon to get better in the future. Longer games produce longer decision trees, the complexity of which increases rapidly with said length. As such, there will always be a path not taken that could have led to victory, so you can nearly always fault yourself in a loss rather than the outside forces of variance.

This means that games of Standard almost always feel skill-intensive and the player who wins can feel like they properly earned it. Mana screw and mana flood still happen, but even these pillars of variance are minimized when the game goes long. Players have time to draw out of poor early hands and get themselves back into the game with strong play.

But in Modern, such early stumbles are severely punished. If you don’t have a turn 2 play or miss an early land drop, you may lose the game on the spot. And even if you draw out of it immediately, the loss of early development will merely produce a slightly slower and more painful death. Modern is, as Thomas Hobbes may have described it, “nasty, brutish, and short.”

Ultimately, what this dichotomy boils down to is that players feel that Modern is significantly less skill-intensive than Standard. So even though the matchups might not change much in Standard, the games are intricate enough to create a good experience. And even though the matchups do change in Modern, the games are unrewarding.

These criticisms are valid to an extent, and I’ll cover how at the end of the article, but my primary purpose today is to expose the major failing of the collective mindset which produced these criticisms, which is representative of one of the most fundamental mistakes that even experienced Magic players make in analyzing the game:

They take much too narrow a definition of what skill at Magic is. More specifically, they place too great an emphasis on in-game decision-making as an indicator of skill, at the expense of all others.

The most skilled players are those who always tap their mana correctly, never miss a free attack, and always extract the maximum value from their cards. They read their opponent for having the removal spell or combat trick and deftly play around it. The best players know how to play to their outs when behind and play around their opponent’s outs when they are ahead.

All of these things are important parts of being a great Magic player, but they all focus on what happens after the cards are shuffled and the first land is played. Magic is so much more than that.

Right now Modern doesn’t stress these skills as much as Standard. But that hasn’t stopped skilled players from winning. Brandon Burton is a talented player who’s been in a win-and-in match for a Pro Tour Top 8. He also has plenty of experience with red decks. The Top 8 in Guangzhou featured Pro Tour Top 8ers Ryoichi Tamada and Kentaro Yamamoto, with the latter playing the same deck he piloted to an 8-2 Constructed record at Pro Tour Oath of the Gatewatch. Even relative unknown Brandon Semerau has a history with G/W Hatebears.

Creatures (30)

- 1 Eternal Witness

- 2 Kitchen Finks

- 4 Flickerwisp

- 4 Noble Hierarch

- 2 Qasali Pridemage

- 4 Leonin Arbiter

- 2 Blade Splicer

- 3 Scavenging Ooze

- 4 Thalia, Guardian of Thraben

- 4 Restoration Angel

Lands (20)

Spells (10)

Unlike Standard, Modern stresses the skills that are demonstrated before a land is played. The breadth of available decks means that you will assuredly play against archetypes that you have not prepared against. Players who try to metagame the tournament by choosing a new deck each week may find they leveled themselves when they get paired against Ad Nauseam twice and Infect zero times.

The best way to prepare for such a wide-open metagame is to have an intimate knowledge of your own deck. Over time, you will run into a larger portion of the metagame and thus gain experience, as well as understand your deck deeply enough to adapt to novel decks on the fly.

Standard is of course the opposite, where the metagame is narrow enough that you can properly prepare with a new deck in a relatively short timeframe and learn most of the matchups that you will face in the tournament. Therefore you are incentivized to change decks frequently and seek the edge gained from being ahead of the metagame.

The shorter, less interactive games in Modern also stress different skills. Mulligan decisions are incredibly important in Modern because you cannot afford to stumble. Most games end with at least one player having unused cards in their hand, so you can more aggressively mulligan to find hands with strong openings. The comparatively longer games played in Standard mean that card quantity is more important relative to early development.

I routinely mulligan marginal hands in Dredge and will go down to five or even four cards in order to find a hand that starts doing relevant things on turn 1. If you need to win on turn 4 against another non-interactive deck, then mulliganing a hand that is 10% to win by then but 50% to win on turn 5 is worth it if your average six-card hand kills on turn 4 20% of the time.

Ironically, the same phenomenon that causes players to dislike this aspect of Modern also makes them play into it: fear of non-games. Players like to feel like they had a fair shot of winning, that they were in control. A game where you never play a second land is the opposite of that, but the reality is that you are in control in those games, since you get to mulligan weak opening hands. It’s just a matter of redefining your definition of weak, given the parameters of the format you are playing.

The need for consistent, strong openers can also be aided in the deck design stage. The lower curve that Modern decks have may seem to suggest playing a lower land count, but condensed games mean that mana screw is far more punishing than mana flood. That additional land doesn’t make a huge difference, but every edge counts over the course of a long tournament.

Moreover, where Standard decks are built to maximize optionality in games, Modern decks need to be built with the same brutal efficiency that is the hallmark of the current metagame. Take Dredge, for example. Shriekhorn is not a good Magic card, but it’s the best card for the job as a third enabler after Faithless Looting and Insolent Neonate.

A lot of players use Tormenting Voice in that spot, which is a more powerful individual card and a better draw as the game goes on, but that’s not what the deck needs out of its enablers. It needs speed and mana efficiency, which Shriekhorn certainly has. You also frequently need your enabler to dig for a dredge card, which Shriekhorn does better than even Faithless Looting.

If the goal were to find the best individual card that can be a graveyard enabler, Tormenting Voice would be the superior option, but with a linear deck, you need the best card in a very specialized role, which often leads to playing underpowered cards. The same can be said of Memnite in Affinity or Spider Umbra in G/W Hexproof. In Modern decks, every card is a cog and your goal is to build the best machine. The decks are more than the sum of their parts. In Standard that difference is much smaller, so it’s better to maximize the power level of your cards in a vacuum.

This paradigm exacerbates the trap of evaluating cards outside of context that many players, even experienced ones, fall into. Everyone wants to shortcut by labeling cards good or bad so they can unilaterally ignore the latter group, thus reducing their mental burden. But context is paramount to card evaluation, even in Standard. Look at Jace, Vryn’s Prodigy, which went from format all-star to almost unplayable upon rotation to solid role-player when paired with the green graveyard enablers post-Eldritch Moon. And in Modern, since the decks are more linear, that context is even more important.

The deck design edges that successful Modern players routinely leverage are often ignored, given the world we live in where access to winning decklists is so widespread, but as I noted earlier, even small changes can have a significant impact over fifteen rounds. I repeat this a lot, but it’s important–Magic is a game of small edges being realized over time. You can do everything right and still lose, or you can do everything wrong and still win. But those who do more things right win more often and vice versa. Ignoring a large number of the skills that make Magic the great game that it is will only set you up for failure.

Now, you may have read all of this as a passionate defense of the Modern format as it currently exists, so you may be surprised to learn that, despite my recent success with Dredge, I am unhappy with Modern as a format right now. I am also unhappy with Standard. But the reason I find them both underwhelming is not because they favor one skill set over another. It’s due to lack of balance.

The best formats have enough variety across all metrics to allow players to exercise a variety of skills to succeed. But in both Standard and Modern, I feel pigeonholed into playing a certain way, which makes the entire experience less interesting. Sure, you can play Jund in Modern or Humans in Standard and go against the grain, but most evidence points to that being a losing decision in the long run, which is a problem.

This isn’t to say that I don’t enjoy playing the kind of linear, proactive decks that are common in Modern; in fact I very much do. Nor do I inherently dislike the technical intricacies a long, complex game of Standard provides. But what I want most of all is the ability to decide my own experience. I want to evaluate a metagame and make my own decision as to what style to play. I want to be in control of the most fundamental decisions, because those are the kinds of questions I like exploring. That’s also why I enjoy writing Magic theory articles and analyzing decks and metagames from a broader perspective.

Magic is an enormously complex game with few, if any, rivals in strategic depth. That is why, regardless of the nature of a format at a given time, there will always be a significant edge for better players. What skills the format stresses may change, but there will always be an advantage to be gained.

And there’s nothing inherently wrong with having certain skills be stressed a lot from time to time, as we currently see in Standard and Modern, although there may be an argument to be made that fast-paced formats make for a worse viewing experience. But personally I want to see the community understand and appreciate the skills outside of in-game play that are just as important to tournament success.