Paulo Vitor Damo da Rosa recently wrote an article on the “Aggro” category of decks and discussed it over Twitter. I feel, while he may be one of the best Magic players in the game, he did not end up furthering the community’s understanding of Magic theory. In all likelihood, it impaired several players’ understanding of what certain terms—aggro, aggro-control, and control especially—mean. How so?

Paulo never defined his terms. This is how he defined aggressive decks:

“As a general rule, aggro decks are not as powerful as the other decks and have more situational cards, though it’s a different kind of situational than you might be used to. This creates an interesting situation in which your cards are incredibly synergistic early on but lose usefulness as the game progresses—ordinarily, one would think the late game would be good for a synergistic deck (since you have more cards to synergize with), but that is not true with aggro. Because of that, you have a goal—you need to win the game before your weaknesses come back to haunt you. With an aggressive deck, your focus should be the early game—that is your domain. Your cards are much better early than anyone else’s, but their cards are better later—as such, you want to kill them before they can play all of them, because they don’t get bonus points for having Titans in their hand when they die. There are two main types of aggro decks—ones with reach and ones without.”

The problem with Paulo’s article is that he really defined “aggro decks” as “anything that relies on attacking in the early and middle game to win.” This sort of definition isn’t helpful for many players’ understanding of the game. Why?

Consider Jund.

Creatures (16)

Lands (25)

Spells (19)

If you were to think that Jund is an aggro deck with disruption, you would play it pretty badly. You’d probably still win a few games off of the overwhelming amount of card advantage in the deck, but that’s not something to be proud of. Jund is a Rock-style midrange deck that can grind people out with the best of them. Still, is that important? What does defining our terms more clearly actually do for us as Magic players?

Why Definitions Matter

Everyone reading this knows about Mike Flores argument that you will lose a game if you don’t assign yourself the correct role within the game. It stands to reason, then, that the same is true of your strategic archetype. Adrian Sullivan, in an article written four years ago on this very site, wrote that, “If you are conceiving of a deck as aggro-control, but in reality you have an aggro deck with disruption or a midrange aggro deck, this failure of understanding can cause you to make strategic or tactical errors both in-game and in your preparations.”

How do we define a strategic archetype then? A few things to understand:

Strategic archetypes are not contextual. They exist outside of any one game of Magic.

This is a big part of why Paulo didn’t understand our conversation about aggro strategies. When we conversed on Facebook later, he came up with a bunch of hypothetical situations that didn’t have any bearing on strategic archetypes. An example:

Q: If my Affinity deck sideboards fifteen counterspells, does it become an aggro-control deck?

A: No, it just becomes a bad deck.

Creatures (26)

- 2 Arcbound Ravager

- 4 Ornithopter

- 4 Steel Overseer

- 4 Memnite

- 4 Etched Champion

- 4 Signal Pest

- 4 Vault Skirge

Lands (16)

Spells (18)

Sideboard

His question was clearly facetious, as he understands that Affinity is a synergy-dependent deck that can’t afford to sideboard in fifteen counterspells. Still, his question belies a fundamental ignorance about the theoretical nature of Affinity—as an aggressive linear deck, there are better and worse ways to combat combo decks.

Let’s say you didn’t know about or care about archetypal distinctions. Aggro, control, who cares? All the cards are the same, right? So you have your Affinity deck and you want to beat Storm. How do you do it? Why not add four Mindbreak Trap to your sideboard? After all, that beats Storm, right?

The thing is, so does Ethersworn Canonist, but Canonist also furthers your game plan. If you draw three Mindbreak Traps in your opening hand, you’re going to get ground out by Pyromancer Ascension. It doesn’t matter that you draw your hate cards if you don’t also present a reasonable clock. Sure, you could sideboard in four Negate, four Dispel, four Remand, and three Delay in your Affinity deck, but what are you sideboarding out? Signal Pest? You can’t play an aggro-control game with Affinity—you need too many pieces to Voltron together to have a bunch of resources in your hand just waiting to interact with them.

If a player completely understands that Affinity’s ideal game involves having an explosive first, second, and third turn, they won’t board in Mindbreak Trap against Storm. Really, Mindbreak Trap won’t be in their sideboard since they’ll understand that their strategic archetype demands better card efficiency than Mindbreak Trap provides. Those realizations are the value of understanding Magic theory terms.

The construction of your deck matters.

During our conversation on Facebook, Paulo asked the following:

“In the end, is there much of a difference between turn 1 Delver of Secrets, counter your Swords to Plowshares and turn 1 Wild Nacatl, you Swords it, turn 2 Kird Ape? How about turn 1 Delver, turn 2 Daze your guy” or “turn 1 Nacatl, turn 2 Path to Exile your guy?”

Yes, there’s a huge difference between those four interactions. There seems to be two issues here—the first is that Paulo doesn’t seem willing to accept that different pieces of interaction are differently meaningful, while the second is that he seems to think that all one-drops are created equal. First, let’s break down what it actually means to have Wild Nacatl, Kird Ape, and Delver of Secrets in your deck, since not all one-drops are created equal.

Wild Nacatl: A bad card without both red and white lands in your deck. This doesn’t inherently imply a given level of threat density, but it does commit you to three non-blue colors. You can certainly play blue in a Wild Nacatl deck…

Creatures (18)

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (22)

Spells (18)

Sideboard

…but that’s the exception rather than the rule. Most of the time, you have more redundancy in your one-drop slot…

Kird Ape: Basically a red, mostly-worse Wild Nacatl in the context of today’s Legacy format. It plays the part of Wild Nacatls five-through-eight, since Nacatl has already committed your mana base to Taigas and Plateaus. Again, you could play this in a RUG shell with no real repercussions, but why would you?

Delver of Secrets: Now this requires commitment. It’s blue and nothing else, so your mana base can be whatever you desire. If you want to flip your Delver, though, you’re committing to three things: a low threat density, a low land count, and a high spell count. Let’s take a look at my RUG Delver list from SCG Open Series: Baltimore featuring the Invitational:

Creatures (12)

Lands (19)

Spells (29)

- 4 Brainstorm

- 4 Lightning Bolt

- 3 Force of Will

- 2 Chain Lightning

- 3 Daze

- 3 Spell Snare

- 4 Ponder

- 4 Spell Pierce

- 2 Thought Scour

Sideboard

Nineteen lands, twelve creatures, and twenty-nine spells. A Delver that flips a full half of the time. Four Wastelands and fifteen colored sources. All in all, a very different deck from a Counter-Cat deck with 24 threats and 21 color-producing lands.

So let’s get back to understanding why Paulo’s comparison between those openings is a fallacy. There’s a very real difference between playing a creature, having it killed, and replacing it versus playing a creature and protecting it with countermagic. For starters, the first scenario requires you to have another creature, while the second scenario requires you to have another counter.

“But Drew!” you might protest, “Daze is like another Delver of Secrets if it protects your Delver! It’s the same thing!” No, it’s not. Tell me how similar these two decks are, and I’ll tell you how well you understand the distinction between aggro-control and aggro:

Deck 1

8 Savannah Lions

4 Faith’s Shield

4 Mutagenic Growth

4 Daze

3 Windswept Heath

3 Misty Rainforest

1 Tropical Island

2 Tundra

1 Savannah

Deck 2

20 Savannah Lions

10 Plains

If you think that these two decks are the same, you’re just wrong. Sure, Faith’s Shield “represents” another Savannah Lions against a deck with twenty Doom Blades, but it isn’t actually providing a requisite level of threat density. If our opponent Tragic Slips our first Savannah Lions, we might be out of the game for lack of another threat. In that regard, the twenty Savannah Lions deck looks more appealing. After all, it can always present a threat on turn 2!

If, however, our opponent tries to kill us on turn 1, I’d rather have the deck with Daze and Faith’s Shield. Our “represented creatures”—Daze to protect a 2/1, Faith’s Shield to do the same—can become ways to protect our face, something that the mono-Lions deck lacks. Against a Tendrils of Agony combo deck, then, the twenty Lions deck is a huge underdog, while the eight Lions deck is just fine.

Calling the eight Lions deck an “aggro deck with disruption” misses the entire point of what it means to be an aggro deck. The eight Lions deck is always going to lose to the twenty Lions deck. Why would one “aggro deck” lose an aggro mirror so consistently? It might have something to do with the fact that the eight Lion deck is an aggro-control deck, an archetype that loses fairly regularly to more aggressive decks.

How Everyone Can Be Right About Aggro-Control (Yes, Even Paulo)

A lot of people playing Magic today grew up believing in a different sort of aggro-control deck. Paulo and I are not that far apart in age, and so we both grew up believing that Faeries was a “true” aggro-control deck. All other aggro-control decks get measured against Faeries, and obviously nothing now looks like Faeries so nothing looks like aggro-control to Paulo. As I learned more about Legacy, though, a bit of historical research taught me that a “real” aggro-control deck looks like this:

Creatures (22)

- 4 Mogg Fanatic

- 3 Spiketail Hatchling

- 4 Voidmage Prodigy

- 4 Grim Lavamancer

- 4 Cloud of Faeries

- 3 Flametongue Kavu

Lands (18)

- 4 Mountain

- 10 Island

- 4 Shivan Reef

Spells (20)

Sideboard

- 3 Chill

- 1

- 3 Stifle

- 3 Cursed Totem

- 2 Gilded Drake

- 3 Submerge

Cheap but effective threats? Check.

Soft countermagic? Check.

More interested with controlling time than with controlling the board? Check.

This was an aggro-control deck I could get behind! It had everything. Let’s look at that RUG list one more time, just to compare…

Creatures (12)

Lands (19)

Spells (29)

- 4 Brainstorm

- 4 Lightning Bolt

- 3 Force of Will

- 2 Chain Lightning

- 3 Daze

- 3 Spell Snare

- 4 Ponder

- 4 Spell Pierce

- 2 Thought Scour

Sideboard

One-drops, Daze, soft countermagic, and an avid interest in controlling temporal advantage? Smells like aggro-control to me.

For those of us who came into Magic in the last five years, Faeries and Caw-Blade are impossible to ignore. They fought so many fights so brutally efficiently that people didn’t know what to call them, so they called them “aggro-control.” The problem with that label is that it conflates Caw-Blade with RUG Delver or forces us to conflate Zoo with RUG Delver. RUG Delver isn’t a bad Zoo deck, nor is it a bad Faeries deck. To fully understand how broadly we can define aggro-control, we needed another term between “aggro-control” and “control.”

Adrian Sullivan gave us the term “hybrid control.”

Hybrid Control

Adrian defined hybrid control as a deck that, “Plays out like a control deck but then is able to create a reproducible late game board state again and again.” Given that Faeries and Caw-Blade didn’t concern themselves with controlling time, Adrian’s description is much more apt.

If you look at 56 cards of a Faeries list, it looks like an aggro-control deck:

Creatures (15)

Lands (25)

Spells (20)

Sideboard

It has conditional countermagic (Rune Snag, Spellstutter Sprite), a few hard counters (Cryptic Command), some removal, and a great time-controlling haymaker in Mistbind Clique. If that’s all you look at, it looks exactly like an aggro-control deck.

The thing about Faeries, though, is that it didn’t need to control time. It had Bitterblossom, which led to “free wins” as a lot of people said. It could play games that involved casting Bitterblossom on turn 2 and winning on turn 7 without tapping any main phase mana on turns 3, 4, 5, or 6. Eventually, people were just dead to your constant stream of fliers. The game-ending board states always looked the same, too: a Scion of Oona or two, maybe a Mistbind Clique, an activated Mutavault, and five 1/1 fliers tapped and attacking with a Rune Snag, Terror, and Cryptic Command in the graveyard. Very reproducible, very scripted, and easy to see from a mile away.

Caw-Blade was the same thing except it had two Bitterblossoms. Some decks couldn’t beat a Stoneforge Mystic, while others couldn’t beat a Squadron Hawk. The people who tried to beat both couldn’t beat a Jace. The people who tried to attack through both couldn’t beat a Gideon. A list, for those of you who want to relive either the glory days or a half-year nightmare:

Creatures (9)

Planeswalkers (7)

Lands (27)

Spells (17)

This wasn’t an aggro-control deck or a control deck; it was a hybrid control deck. Caw-Blade was never concerned with controlling time—in almost every case, time was on its side. It didn’t need to care about any of its threats too much because it could attack from a number of different angles, and eventually one of those angles of attack would defeat the opponent. How can we demonstrate this?

Well, what usually matters in a control mirror? Cards, right? Except Caw-Blade mirrors didn’t come down to that. People died with Jaces in hand and up five cards all the time. It wasn’t an uncommon thing to have happen.

What matters in an aggro-control mirror? Trumps, right? In a Legacy RUG Delver mirror, Tarmogoyf is king. The real advancement in my SCG Invitational RUG list was adding two more Tarmogoyfs to the sideboard that had incidental value against certain linear strategies, since they would also crush the mirror. The reason why I beat Caleb so convincingly in our match was because I had Tarmogoyfs and Spell Pierces to his Green Sun’s Zeniths and Stifles. Usually there’s something in an aggro-control mirror that beats everything else, so winning those mirrors involves drawing more of that thing or finding ways to play more of it.

The problem with the Caw-Blade mirror is that everything mattered at different points. You could lose to Hawks, Swords, Jaces, Gideons, Tumble Magnets…you name it, you could lose to it. There was no real trump in Caw-Blade mirrors. So what mattered? How did you get ahead? What was the important factor, even more important than card advantage?

The same thing that mattered in the Faeries mirror: board advantage. People attributed Bitterblossom with winning all those mirrors because it did. There was nothing that could reasonably answer its advantage, so the only good strategy in a Faeries mirror where they had Blossom and you didn’t was to race them. Gerry Thompson boarding in Fledgling Mawcors in the Faeries mirror was like boarding in Day of Judgments in the Caw-Blade mirror—sure, it might look like you’re solving the problem, but you’re not actually doing anything to win. Besides, your plan (Fledgling Mawcor/Day of Judgment) loses to other good cards in the mirror (Cryptic Command/Terror/Rune Snag/Spellstutter Sprite and manlands/equipment/planeswalkers). Understanding how matchups work on an archetypal/theoretical level is immeasurably valuable; more on this in a second.

Gerry Thompson put hybrid control in a slightly different light. He said that, “The goal of Faeries and Caw-Blade was always to get them to a point where they were drawing dead.” A lot of people made decks that were just drawing dead to a Bitterblossom. Some decks were drawing deck to a Mistbind Clique. People designed a lot of decks that were drawing deck to a Sword of Feast and Famine.

An important distinction to keep in mind is that the point between “having them drawing dead” and literally winning the game gets longer as you move toward a more controlling deck and shorter as you move toward “purer” aggro-control decks. Faeries players generally knew that they were going to win three or four turns out. Caw-Blade players could have people dead to their Jace and Gideon on turn 5 and the game could drag on until turn 12 with the opponent having zero chance of winning the game. Merfolk decks generally knew that their opponent was dead before the two turns of alpha strikes it took to finish them off, while RUG Delver decks rarely have it in the bag more than a turn out. Aggro players, by definition, never have someone drawing dead. They can just kill someone, but they’re never at a point where they have their opponent drawing dead.

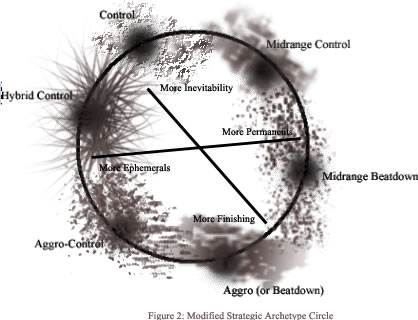

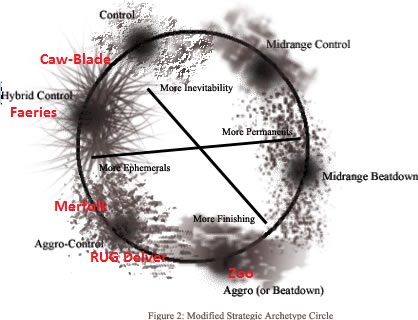

Adrian created a nice diagram that time has since forgotten but which still has a lot of utility:

The focus of this article is on the area between 6 and 11 o’clock on his circular diagram—the space between aggro and control. The inkblots are there to remind us that there’s significant bleed between archetypes, which is why Paulo isn’t entirely wrong. To create a spectrum of the space between 6 and 11 on that circle, we have no shortage of examples:

In Conclusion…

…RUG Delver is still not an aggro deck, Faeries and Caw-Blade are still not aggro-control decks, and people can gain a lot of value by using the terms properly. I’ll leave you with two final examples:

First, how many more top eights do you think Gerry Thompson would’ve made if he wasn’t trying to make Faeries a control deck? That is, what if future-him came back and told him that Scion of Oona was a really important part of the deck and to stop trying to make Fledgling Mawcor and Nameless Inversion happen?

Second, to return to my previous point, how many Top 8s would literally anybody have made in the Caw-Blade era if they had known that Caw-Blade was a hybrid control deck? What if people were just jamming Jace Beleren into Hero of Bladehold from the get-go? What if people had showed up with a good list of Caw-Blade that had Mortarpod in it on week one?

How long will it take for people to figure out how good Lingering Souls really is?

@drewlevin on Twitter