In a previous article, I talked about non-rare Cubes and why you should make one. However, in that article I didn’t go into detail about the different contexts of those types of Cubes off the beaten path. In this article, I’ll be discussing the first of those types of alternate Cubes: Pauper. Ryan Overturf wrote an article about the format earlier this year. I’ll talk about the differences between Pauper Cubes and "regular" Cubes and the design implications to make and learn from. Throughout this article when I say "regular" Cubes, I’ll be referring to Cubes with rares in them. This is because although there are Powered and Unpowered Cubes, both of those comprise the majority of Cubes; Cubes with rares are what most people think of when someone asks them what a Cube is.

Commons are the bread and butter of Magic sets, as they’re used to emphasize the themes of the set, and the New World Order as outlined by Mark Rosewater heralds a design ideology to pursue this further. Because of this, Pauper Cubes can play closer to the Limited side of Magic than Constructed, although the usual rules of needing to construct a deck and not just a pile of cards still apply. Although Cube matches are defined by creatures, Pauper Cubes tend to have more creature than regular Cubes tend to. Most regular Cubes usually have a nonland split of creatures and noncreatures that’s pretty even, but Pauper Cubes tend to lean towards creatures since Limited formats are defined by their creatures as a central tenet and avenue of victory.

The overall power level in a Pauper Cube is flatter than in a regular Cube, which can be a draw for some who have been burnt out by regular Cube formats. There’s still an upper tier of cards in Pauper, like Guardian of the Guildpact, but the power level between that tier and the average tier tends to be a smaller differential than what it is in a regular Cube environment. I have had a Pauper Cube for several years and have learned various lessons from designing it. When thinking of Pauper Cube, both from a designer and drafter point of view, it’s important to note the differences in the formats—it isn’t just a lowered power level that separates them.

Mass and Spot Removal

In a regular Cube, it’s frequent to see mass removal effects as a core strength of control decks; while white has historically been the main color of wraths, other colors like red (Earthquake, Rolling Earthquake, Mizzium Mortars, Wildfire) and black (Damnation, Decree of Pain, Bane of the Living) share that strength as well. Since mass removal effects aren’t a theme that designers want to have as a bread and butter effect in Limited formats, you don’t tend to see mass removal very often in Pauper Cubes, with cards like these comprising to define mass removal:

At least in the traditional sense. Most of the format’s mass removal manifests itself in cards that two for one an opponent, like Serrated Arrows, Pyrotechnics, and Ashes to Ashes. You may be thinking that it’s odd to want to take a card like Ashes to Ashes highly—even over cards like Doom Blade—but it’s important to note that context matters.

Due to the higher density of creatures in the format and the almost 100% certainty that they can be used for attaining maximum value combined with the lack of traditional mass removal, they’re relatively high picks and ones that I’m always happy to play even in the most aggressive of aggressive decks. A card like Ashes to Ashes or Undo would be dubious in a regular Cube format since the certainty of hitting two creatures is much lower, but it’s much higher in Pauper.

That said, even though mass removal effects tend to be very good in normal Limited formats, that adage doesn’t apply directly to spot removal. In some formats, removal is intentionally curtailed, like Avacyn Restored and Shadowmoor / SSE, to emphasize certain elements of the format (soulbond and Auras respectively). For the most part, removal isn’t highly represented at common, and the ones that are high picks.

In a normal Limited format, a card like Rend Flesh or Eyeblight’s Ending can be a high pick due to the lack of removal, but because there’s a higher quantity of quality cheap removal, the need to take spot removal in Pauper isn’t as high because the density is similar to a regular Cube (even if the best ones like Swords to Plowshares and Dismember don’t make it over). I tend to value spot removal in Pauper Cubes about as highly as I do in Cubes with rares and have designed my Pauper Cube accordingly.

It’s a common pitfall to see an overrepresentation of inefficient spot removal like Eyeblight’s Ending, Arrest, and Rend Flesh and overly valuing pingers like Prodigal Pyromancer and Chainflinger in Pauper Cube due to outsourcing evaluation to other formats, but the lesson to take from it is asking yourself why you’re valuing those cards highly in other formats and if that same context applies to a Pauper Cube.

Finishers

Even though things like spot removal transfer over from regular Cube to Pauper, the same can’t be said of Pauper Cube finishers.

Unlike in regular Cube, the finishers aren’t of the traditional type of the "big creature with some form of protection" that define the modern Cube finisher, such as Wurmcoil Engine and Elesh Norn, Grand Cenobite. A lot of the finishers in Pauper are closer to things like Noble Templar and Havenwood Wurm, which don’t have the best methods of protection and can fail the Vindicate test. Finishers that protect themselves, like Scuzzback Marauders, Shimmering Glasskite, and Penumbra Spider, aren’t numerous.

Without planeswalkers and a dearth of Titan-esque finishers, what incentives are there to go big in Pauper Cube? This was something that I ran into when I was developing my Pauper Cube. Since the first Pauper Cube that I drafted (and a lot of my other regular Cube draft experience with other Cubes locally) had nearly unplayable aggressive sections, I went too far the other way, as I received feedback that there weren’t enough finishers. So what did I do? I shifted my expectations for my finishers.

A lot of the options for finishers in a regular Cube have built-in protection that focus on value, like Inferno Titan acting like Arc Lightning and Yosei locking an opponent down, to supplement their bodies. In my Pauper Cube, a lot of the finishers that deliver on raw stats weren’t performing well due to vulnerability to spot removal and weren’t giving control players good incentives to go big.

I have found that it’s better to focus on what’s making modern finishers perform well by centering less on raw stats and more on value by having the finishers go along with what those decks want to do.

Admittedly, these aren’t as good as stabilizing the game as something like an Elesh Norn, which does something and requiring an immediate answer, but they do work along with the goals of those decks by either providing modular value depending on the game state or outclassing opposing creatures while providing value. In the case of Totem-Guide, it works well with a white control deck’s goals as a toolbox that does what the deck wants to do anyway (fetch Auras since a lot of white removal is in Pacifism form in the format).

It wasn’t until very recently that we got some solid midrange creatures at common that battle purely on stats. I remember talking to fellow Pauper Cuber Adam Styborski about which 4G 4/4 was better (Barkhide Mauler, Spike Colony, or Stampeding Rhino) because the options were that weak. Recently, we’ve gotten some better options, which I hope is a good sign for the future.

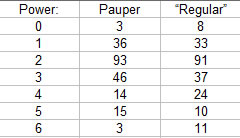

Because commons make up Limited formats, creatures tend to be on the smaller size; this is doubly important because of the creature-centric focus of the format. It’s interesting that the creatures of Pauper Cubes tend to cluster at smaller sizes than in regular Cubes, with the density focusing lower than in regular Cubes.

You’ll notice from the picture that although the power numbers are pretty close until two power, the density of power is a lot smoother of a decline in a regular Cube than in a Pauper Cube, showing that the format’s creatures tend to cluster between one and three power. Due to this clustering, a card like Vulshok Morningstar can get a ton of value by making creatures nearly unkillable in combat, like turning a 3/3 into a 5/5.

This also applies to the smaller size of evasive creatures in the format since flying creatures tend to top out at three power because Air Elementals have almost exclusively been printed at uncommon. Because of this, cards like Illusionary Forces and Windrider Eel get a power boost, and creatures like Skittering Skirge become more threatening since it usually puts the onus on the opponent to kill it quickly, which doesn’t apply as much in a regular Cube. This can apply to Skittering Horror as well due to four power even if it isn’t evasive.

On the other side of the spectrum are aggressive creatures and their support.

2/Xs for one aren’t as frequent because they aren’t the bread and butter of many formats, with a few exceptions like Steppe Lynx, Vampire Lacerator, and unplayable ones like Bloodcrazed Goblin and Accursed Centaur. There are only 29 in Magic, 30 if you count Steppe Lynx.

In a regular Cube, a 2/X for one in the sideboard of an aggro deck means either the deck isn’t actually an aggro deck or a deckbuilding error. Options are much more limited because aggressive decks, at least ones that start at one mana, aren’t pushed in normal Limited formats because aside from a few exceptions like Zendikar many of their curves start at two. We can apply that lesson to Pauper Cube (although note that we don’t want it to be such an aggro fest that control decks are unplayable a la Zendikar) by looking to other areas in the aggro curve in the two-to-three mana range.

In the same way that cards like Molten Rain, Wrench Mind, and aggressive creatures support a game plan of winning the game ASAP, the same tenets apply by looking at efficient creatures like Splatter Thug, Hungry Spriggan, and Inner-Flame Acolyte to supplement early creatures, even with the lowered number of one-drops in the format. In the same way that you want to provide adequate incentives for control decks to grind out value with their finishers, so too do there need to be incentives for going aggressive by providing enough support at the one-to-three mana range.

Fixing

Even though blocks like the original Ravnica, Return to Ravnica, and Shards of Alara emphasized multicolor, the overall amount of common mana fixing is quite low since there have only been a few staple cycles of mana fixers in the format (Guildgates and Borderposts), both of which enter the battlefield tapped to the chagrin of aggressive decks. In those formats, aggressive deck considerations weren’t really an issue since those decks weren’t meant to be a big force in the format, and as such the drawback really wasn’t that bad for them; even Zendikar’s limited mana fixing (the Refuge cycle at uncommon) entered the battlefield tapped.

I didn’t mention bouncelands and Signets as staples since there are Cubes that don’t use them because of people thinking that they make aggro decks bad (tl;dr: they don’t) and in Pauper the same applies. The issue is compounded further because due to the lack of mana fixing lands that enter the battlefield untapped, aggressive decks frequently use mana fixers like bouncelands. In a Pauper Cube, I’m happy to play a Gruul Turf due to limited options, whereas I wouldn’t normally want to do so in a regular Cube aggro deck.

Like in a regular Cube, a Pauper Cube can be designed to only include the Signets / bouncelands / Cluestones that are preferable to the color combination (a Rakdos deck probably wouldn’t want a Cluestone). However, unlike a regular Cube where there are more aggressive leaning options like painlands and the Scars lands to act as counterpoints to the more control-friendly ones like bouncelands, there are few options for multicolor fixing in Pauper.

Design Considerations

One of the positive aspects of Pauper Cube design for people who want to understand the nuts and bolts of Cube design is that it’s inherently self-restricting and self-disciplining. A common pitfall in regular Cube design is seeing Cubes with a disproportionally high amount of multicolor cards and finishers that naturally restrict themselves because there just aren’t that many to go around; it’s much harder to overload on those types of cards in Pauper.

Masters Edition Sets

Another thing to consider when designing a Pauper Cube is that a Pauper Cube can (if the designer chooses) include cards from the online Master’s Edition sets. The following is a list of cards that are common in Master’s Editions 1-4. (These are the main ones to consider since there are a lot of bad ones out there like Adarkar Sentinel and Ebony Rhino).

Aeolipile (Rare)

Armored Griffin (Uncommon)

Brass Man (Uncommon)

Brilliant Plan (Uncommon)

Death Spark (Uncommon)

Exile (Rare)

Fellwar Stone (Uncommon)

Foul Spirit (Uncommon)

Hyalopterous Lemure (Uncommon)

Icatian Lieutenant (Rare)

Icatian Phalanx (Uncommon)

Ogre Taskmaster (Uncommon)

Onulet (Uncommon)

Phantom Monster (Uncommon)

Primal Clay (Uncommon)

Shield Sphere (Uncommon)

Shu Soldier-Farmers (Uncommon)

Strategic Planning (Uncommon)

Section Sizes

In the early days of cubing, the size of each section of a Cube was rigid since the idea for a Cube and the name itself hinged on all sections being the same size. There was an exception for multicolor section to be bigger to allow for one of each tricolor card, but design has become more elastic as people realized that those constraints are unnecessary. We can apply this when thinking of section sizes in Pauper Cubes.

In many Cubes, the artifact / colorless section can be as big or bigger than a color section. For example, in my 460-card Cube, I currently have a colorless section of 75 cards, but the artifact section of my Pauper Cube is much smaller. This is because a lot of artifacts at common just aren’t very good. Aside from a few all-stars like Bonesplitter, Vulshok Morningstar, and Serrated Arrows, the quality of artifacts in Pauper drops very quickly, resulting in a lot of filler. I previously used artifacts like the mana Myr, Chromatic Sphere, Chromatic Star, and others to flesh the section out, but instead of supplementing the sections and guilds, they were mostly filler, so the slots are better utilized elsewhere.

It wasn’t until Return to Ravnica block was complete that multicolor became fleshed out for a lot of sections, such as Simic and Orzhov; it was common to see cards like Winged Coatl in Simic because options just weren’t there. Much like in a regular Cube, some sections have an embarrassment of riches (like Selesnya), but the other sections have gotten to the point where they are a few cards deep. As mentioned earlier, the options are naturally restrictive, meaning that a Cube designer won’t be able to overload on multicolor cards since a lot aren’t very good. As such, I recommend three or four multicolor cards per guild.

In the past few years, we’ve seen sets created with more dynamic commons and interactions that emulate themes in regular Cubes. Pauper Cube is a wonderful alternate to regular Cube that can teach you a lot about how to design with natural restrictions. I hope that this article gave you some insight into the world of Pauper Cubing.

May your opening packs contain Sol Rings!

@UsmanTheRad on Twitter

My blog with 450-card Pauper and 460-card Powered Cube lists: I’d Rather Be Cubing

Cube podcast that Anthony Avitollo and I co-host: The Third Power