Mark Rosewater article on Monday, December 5th about the “New World Order” and the new directionality of Magic design may be as important to the future of Magic: The Gathering as the recent announcement about the changes to organized play (OP; i.e., loss of Worlds, etc…). Interestingly, though, because the premise of the article isn’t alarmist in nature, and perhaps because it’s about a way that Magic has become a better game for players at all levels, it hasn’t attracted a lot of attention on the Internet (relative to the previous announcement about OP changes). What this says about the group psychology of Magic players is a topic for another article, but it’s worth noting that I haven’t seen many social media tweaks (Facebook, Twitter, etc…) about this article, and those that exist are a quiet whisper next to the raging firestorm of criticism—my own included—through which we recently emerged.

While the death of Magic via OP changes has been on everyone’s mind, an arguably more realistic scenario was posited in Gavin Verhey 2010 article “The Day Magic Died.” While he interestingly predicts changes to the Pro Tour structure as being a stressor on Magic’s success, he ultimately posits that Magic will die in the future as a consequence of increasing complexity. While not a direct response to Gavin’s article, Rosewater’s explanation of the New World Order, a paradigm shift in design, answers his concern astutely.

At a basic level, the New World Order begins with the assumption that newer players own fewer cards, often from introductory sets or booster packs, and therefore have a higher percentage of commons in their collection than more advanced players (though in my case and I suspect in the case of many others, I have hundreds of thousands of commons that sit in dusty boxes and simply aren’t circulated in my collection as frequently as common, uncommon, and rare format staples). There is therefore a conclusion that can be drawn with regard to complexity: “The theory behind New World Order was this: we have to be very careful about what we put at common. We had to redraw the line for what level of complexity was acceptable.”

Upon reading this, my first thought was that commons haven’t been overly complex in recent years. I recalled my younger self’s frustration with cards like Ice Cauldron, which was so complicated that even my immature inclination became utilitarian: “No possible effect within a game could be worth reading that or figuring out what it means.” But then I thought about one of my favorite blocks: Time Spiral. There were some commons in that set that were far too complex easily to be understood by those trying to learn the game.

As a common, Aether Web requires knowledge of the following Magic concepts:

- Creature Enchantments (Auras)

- The stack (Flash on an Aura forces comprehension of the stack to demonstrate why the card has meaning)

- Instants

- Counters (+1/+1)

- Combat

- Flying and the associated rules

- A sub-rule within the game that allows the rules of flying to be broken

- Shadow and the associated rules

- A sub-rule within the game that allows the rules of shadow to be broken.

For the more focused learners, one might also ask why Aether Web allows creatures to be blocked as though the enchanted creature has flying but lets you block creatures with shadow as though they didn’t have that ability (i.e., the property of Aether Web appears to function differently with flying—imagined addition of a property to the enchanted creature—and with shadow—imagined revocation of a property from an attacking creature).

This is not a card that effectively can be used to teach the game of Magic, nor is it sufficiently powerful to be found at the uncommon, rare, or mythic rarities—as such (and I presume much in this next statement)—it probably would not see print in its current form under the supervision of Magic’s New World Order.

Now, let’s consider the commons in the most recent expansion, Innistrad. With the exception of Blazing Torch, which is a reprinted uncommon, there are no commons in this set with more than two abilities or functions. Further, there are multiple “vanilla” creatures (Riot Devils, Fortress Crab, Kindercatch, Thraben Purebloods, and Rotting Fensnake). These cards provide a lot of flavor and variety while making Innistrad’s common suite easily understandable to newer players. Now that complexity more closely is tied to rarity, the flavor associated with these cards also is conveyed more effectively to new players.

For example, as vampires become more complex in the world of Innistrad, they often become rarer and more powerful. Beginning with Markov Patrician, for example, which is a French vanilla creature (and a flavorful one to boot—vampires stealing life), one can imagine the slightly more complex Rakish Heir as being less common in the world of Innistrad—their role is more constrained, they appear less frequently, and consequently they are more complex and powerful. This is a trope understood by most role-playing gamers and others involved in similar activities. Finally, at the level of mythic rare, Olivia Voldaren is fairly complex (flying in addition to two activated abilities with significant rules baggage). She’s also powerful enough to see increasingly significant Standard play at the highest levels.

That having been said, we might anticipate several concerns or complaints about this apparent “reduction in complexity”—which is not a true reduction but rather a more reasonable redistribution of these elements with player acquisition and retention in mind.

Concern #1: Commons without unique features won’t be as resonant with players.

This is a reasonable concern. What allows players to distinguish Ironroot Treefolk from Nema Siltlurker or Siege Mastodon from Thraben Purebloods? While the most serious and utilitarian of Magic players won’t care which card is which (they just know when their deck needs a vanilla 3/5), Magic’s R&D does a sufficiently good job at generating worlds (“planes”) that the flavor of the cards should subsume the similarity in function between cards. For example, I’m not “overly” interested in flavor, but I was able to rattle off (in my head, at least) the five vanilla creatures in Innistrad and at no point confused them with their isomers from other planes. If Magic were a game like poker (i.e., without flavor), then this would be a much more significant concern. Further, given the different types of “simple” mechanics that exist, there isn’t likely to be significant levels of repetition. For example, Riot Devils is only the second 2/3 vanilla red creature for a mana cost of 2R in the history of Magic.

Concern #2: While Rosewater effectively argued that the game is not necessarily less interesting when commons are less complex, wouldn’t it ruin drafting?

As tempting as it is to beg off of this question simply by citing the general sentiment that Innistrad is one of the best drafting environments that we’ve seen in a long time, it’s worth illustrating precisely how even more simplistic commons lend themselves to interesting drafting. Let’s examine, in particular, one of my favorite draft archetypes in the last few years.

I’ve fallen in love with Burning Vengeance. At the uncommon rarity, Burning Vengeance is fairly simple. In essence, it says, “When X happens, do Y.” The increased complexity of this card versus a common stems from the fact that it is an enchantment that only does something in conjunction with other cards (i.e., complexity through interaction). Cards like Think Twice and Geistflame provide the common-level fuel for this deck, and vanilla creatures like Riot Devils and Fortress Crab often provide the minimal level of ground presence that the deck needs to establish itself. Despite the relative lack of complexity of many of the uncommon and common cards used in the archetype, it is quite powerful (though niche and unsupportable if multiple drafters fight for it), and it is considered to be “more complex” than many other archetypes, even those with individually more complex cards.

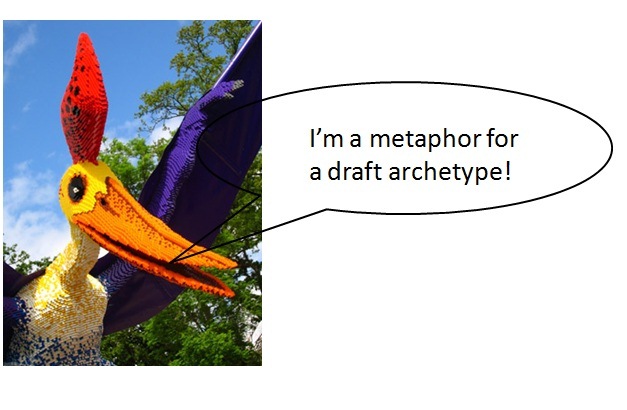

What is created with the “simple” building blocks represents meaningful complexity, much like the giant dinosaurs at Lego Land.

At least from a reader’s perspective, this is what I understand Rosewater to mean when he says “Creating cards that are useful in one type of deck but poor in another makes commons that are strategically dynamic without being confusing for the newer player.”

In “The Day Magic Died,” Gavin discusses several fictitious cards as examples of how “complexity creep” destroyed the game (in a fictitious future, I hasten to reiterate, to avoid repeats of the War of the Worlds radio broadcast). He argues, however, that it was not the individually complex cards that destroyed the game, but the precedent that had been set. What has been done once can be done again with fewer questions, we intuitively understand, and so it is important that Magic R&D continually conducts process evaluation—self-reassessment—to ensure that it is creating precedents that help the game and steers away from those that might harm it. In this vein, Rosewater’s article was one of the best I’ve read in a long time. It was well-written, as always, but more importantly, it showed that R&D is still invested in Magic.

Mark et al have given us a wonderful batch of Lego blocks with which to play in Standard, Block, Modern, and Legacy—not to mention a great draft format. I don’t think that the Standard format has been solved yet, although Illusions and Wolf Run Ramp seem to be the strongest contenders at the moment.

Go out and build something.