So Rakdos is unplayable in the metagame, the Go-Sis deck and surrounding articles are just the latest in a long line of disappointments, and I am completely off-base about powerhouse deck-in-waiting Dredge; I had better just wait for those Regionals results.

Please excuse me for a moment…

Neener neener neener.

“What brings on the above neener trio?” you ask.

Of the literally hundreds of Dredge decks played at the recent U.S. Regionals versus the tiny handful of Rakdos decks, how many more Dredge decks won invitations?

Any guesses?

One.

One deck.

Granted, we don’t have all regions reporting, and Lincoln saw an undefeated Dredge concession when it came around to blue envelope time, but even if Dredge put up Gruul numbers (it didn’t come close), Rakdos was clearly a better choice. In fact, if you lace together the two Rakdos victories with the one Go-Sis (24 hours after the latter deck‘s creator decried it in favor of Rakdos, playing neither), you have exactly the same number of invitations that Dredge, which created double digits in angry forum posts, earned.

I repeat:

Neener.

Neener.

Neener.

Which brings me to another topic. Recently I did some soul searching. Usually I try to ignore forum trolls and pointless negativity in general, and for good reason. For every one of these:

Bertu: No good deck in Extended pays 5 mana for a 4/4. Some decks pay 5 mana for an 8/8, and they are still bad.

Or these:

BBKahuna: After building this deck and playing it online, I can verify that it in fact beats nothing. Aside from TEPS, because GG when you draw any two of Trinisphere/Blastminer/Grudge. Scrabbling Claws do absolutely nothing.

I have found that you are immediately vindicated by the blue envelope (thanks to Michael Le).

However, I take criticism from certain wings very seriously, and try to keep in the good graces of most Pro Tour Champions (especially those who probably only won because they swung down to NYC from Dutchieland to partake in Plataforma with moi pre-teams to turbo charge their mojo). Therefore when Jeroen – who a year ago was reading Deckade as night-night stories over the phone to Terry Soh – told me he hated my writing for something like the last six months, I was forced to think about it, bend back and dog-ear the pages, figure out what was what. My conclusion…

Honestly, I don’t see it. The whole forums eruption took place over a point where I actually produced awesome deck lists that qualified a small handful of actual humans for their Nationals (with insane slugging averages, mind you), and where I criticized a deck – a playable deck, fine – that did worse in the final standings than Chapin Korlash, forgotten Zoo, Project freaking X, and if you want to talk statistically, The motherloving Rack.

During the first part of the year, I correctly predicted Detritivore, got “Ah, the classic strategy Mike that we all know and love. Fantastic and wonderful article. It made me more comfortable in some of my theories, while simultaneously giving me new theories to consider. Bravo!” for The Big Idea, “I can’t believe there is not more discussion here. It’s difficult to describe how much I loved this article,” for Bits and Pieces — The Traits of a Great Deck Designer, and “This was one of the best articles that I’ve read in a long time,” for Three Perspectives: A New Deck for Extended (which is actually one of my favorite articles I‘ve ever written). On top of that – I’m actually going to say this instead of beating around the bush because I’m meant to be madly arrogant anyway – I think the Vectors article with the Rakdos deck (Road to Regionals: Dodgeball, or “Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Vore?”) is going to end up quite important, and I personally thought it was rather good.

Now about the Vectors… I don’t mean this to be knocking Sean over much, but that whole webs / axis re-extrapolation… That’s not even remotely how Magic works. I mean, I dumbed the Vectors down to some really stupid Kyle Sanchez illustrations, but at a macro level, direction is extremely important because side boarding – and positioning in general – is largely about aiming. Vectors in specific might have been a stretch because 1) people who don’t know mid-high level basic math don’t really understand them, and 2) self-important people who think they do understand Vectors would rather nitpick the analogy than try to figure out how applicable it is to Magic (my guess is that the people who didn’t like the Vector analogy are the same people who didn’t like the last episode of The Sopranos). If you didn’t read Sean’s follow-up article, sorry to bore you.

There are numerous reasons this whole axis-web analogy fails. One is that decks only tend to interact one way unless the player who is “supposed” to win is making mistakes. If someone wants to throw the game away (a great example would be me tapping my Serrated Arrows to kill Birds of Paradise and Wall of Roots instead of leaving them up, or at least gunning down Saffi), then the numbers don’t mean anything anyway. More importantly, the beatdown comparison between, say, Gruul and some heretofore-unknown U/W Skies deck, only holds if the decks agree to race (I assume they are agreeing to race, but I have never seen the said U/W Skies-beatdown deck). Why in the hell should U/W agree to this field of battle, fitting snugly under the superior web-area of Gruul? Hasn’t he ever heard of Gruul?

The directional element of the Vectors analogy has to do with one party and another agreeing on the field of battle, or not. Most of this actually takes place in the brains of the combatants, and only manifests itself on the table because that is how the players choose to act. Models like Sean’s might appear to work, but that is only because most people play on autopilot and don‘t really think about how they should be trying to win. Have you ever walked the opponent through exactly the plays you wanted him to make? Have you ever been herky-jerked around like a marionette? It happens all the time. Autopilot. I find this pretty easy to do in Limited at the PTQ level, where I move my guys around setting up the “optimal” blocks for the opponent before going alpha with a bag of tricks in my hand. What often happens in sideboarded games – and I hate this – is that one player decides to make the game about a card like Circle of Protection: Red. Now he has to draw Circle of Protection: Red or he’s going to go home all “wah wah mommy,” and now the other player is expected to accept that the damn game is about Circle of Protection: Red or whatever, and he’s all figuring out Winter Orbs and Manabarbs and God only knows what else, when in fact he doesn’t have to let the opponent pick what the damn game is going to be about. Frankly, that’s AFC talk.

One thing that I have figured out over the past couple of months, especially working with Billy, is that in a real format (not a prop format like Grand Prix: Columbus, or anything similar) you can get a 6/10 or a 7/10 matchup out of any deck, at almost any deck, if you are willing to work at it. I think that what I said recently is “Your opponent puts you on a six and you present… a bag of oranges.”

Sure, if you are going to play by the opponent’s rules, and you hurt yourself, and he hurts you, and you both burn, but his guys are bigger, and he has fewer lands, and it’s all about trading, and you accept that your main deck configuration should be your life’s identity, and you build and sideboard to follow a single axis where he is better in some qualitative (quantitative?) sense… then yes, Sean’s model is going to look like it works fine and dandy. The main way that you win there is to defy the opponent’s expectations while sideboarding. What does this mean? You simultaneously blank his sideboard cards, throw him for a loop, force bad mulligan decisions, and attack from an unexpected angle. The reason that I dislike the web / area analogy is that when you are attacking from “the unprotected flank,“ the rest of the area ceases in large part to matter, if your will is strong enough. You can still fail, of course, but I really don’t see why multiple axes matter in a matchup, say, where neither deck is expert (who cares which of two beatdown decks has greater main deck combo defense, except where such opportunity cost punishes anti-beatdown or forward-moving capacity for interaction?). The web analogy fails, concretely, with a single fatal sin: It violates the only strategic maxim that actually matters in Magic: Focus only on what matters. As soon as you mis-identify the actual strategic avenue you should be pursuing, you make decisions to try to let combo decks go off and then clean up by decking them (?), or tactically shooting mana accelerators when the opponent has sufficient lands in play instead of Saffi Eriksdotter, or devoting what should be cogent resources to any number of other worthless side projects. Anyway, you can accomplish effective strategy in the face of superior quality via either tweak or transformation, though Dave Price could do it just with his demeanor. Go back and review some Price or Maher tape. Come to think of it, Jan-Moritz Merkel did an awfully good job of asserting a length of iron-willed puppet strings in Kobe. The opponent does whatever these champions want, accepts whatever they insinuate should be important, regardless of the tools Dave or Bob (or Jan) actually had at hand. For us mortals, though, a good example would be Kamigawa Block Critical Mass:

Creatures (17)

- 4 Sakura-Tribe Elder

- 1 Isao, Enlightened Bushi

- 4 Meloku the Clouded Mirror

- 4 Kodama of the North Tree

- 4 Keiga, the Tide Star

Lands (23)

Spells (20)

In Game 1, you have a number of advantages over, say, Block Jushi Blue. It is basically the mirror (you have a lighter, if still relevant, counter base) and the same end game of Keiga and Meloku (you actually probably out-gun them unless they‘ve severely out-drawn you). You have an advantage early game in that Sakura-Tribe Elder is much better than Jushi Apprentice for two reasons: 1) Sakura accelerates into a threat and jumps curve if the opponent taps, and 2) Jushi only gains value if the opponent expends mana. Therefore you can tempo the opponent and his Jushi will play essentially blank. Any opportunity to stick North Tree is probably game over if you can counter once. I found that opportunity would arise most often when the opponent would often play some sort of unplayable 0/2 for five mana and then end up dying with 100 cards in hand.

Now what happens in the sideboarded games? Jushi is very cross. His main anti-beatdown weapon is Threads of Disloyalty. They are blank in Game 1… They can steal Sakura-Tribe Elder, but we all know how that goes. Therefore the Threads come out. What is the Mass plan? Bring in both a Threads target in your own Jushis, and bring in Threads for their Jushis. What ends up happening is that you can play either proactively or reactively in the early game, you have the opponent outgunned 3-1 in pre-turn 5 plays, and his life is miserable. You have your Jushis… You have his Jushis.

One of the challenges we had in Pro Tour: Honolulu (Osyp URzaTron) testing was beating Glare if they could stick multiple North Trees. Really, the only option is to trade (usually at value for them), so running out of Keigas and Melokus (ack) was a problem if they played right. Osyp figured out that supplementing the Blue Legends with Ryusei was a good option because it savaged the Glare board at the same time that it traded with North Tree. Block Jushi is figuring out the anti-North Tree plan (forget about the fact that you actually have them covered on Blue Legends)… Your game plan is to completely take over a different part of the game, one that they walked away from, and dominate on early game tempo and card advantage. When it comes time to fight over North Tree, Keiga, whatever, you will be so far ahead on cards that nothing they do matters.

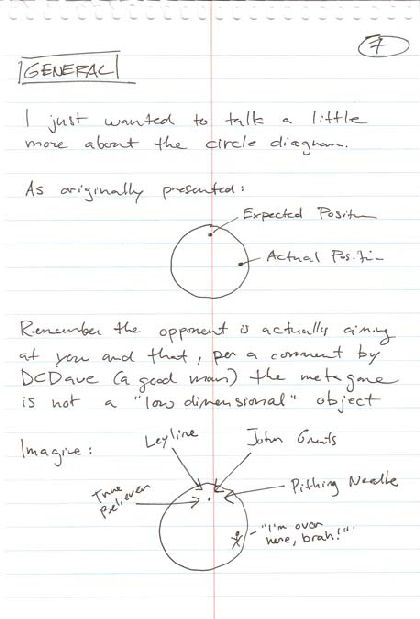

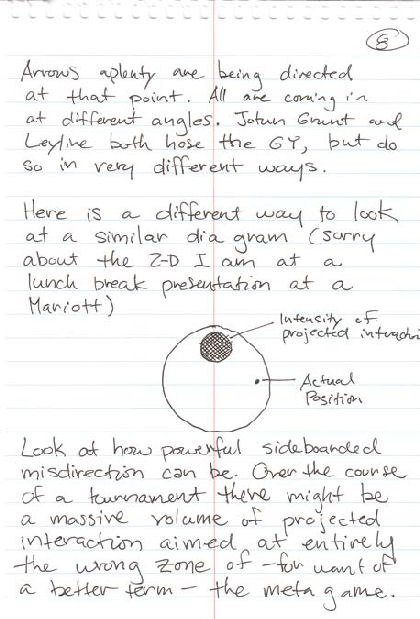

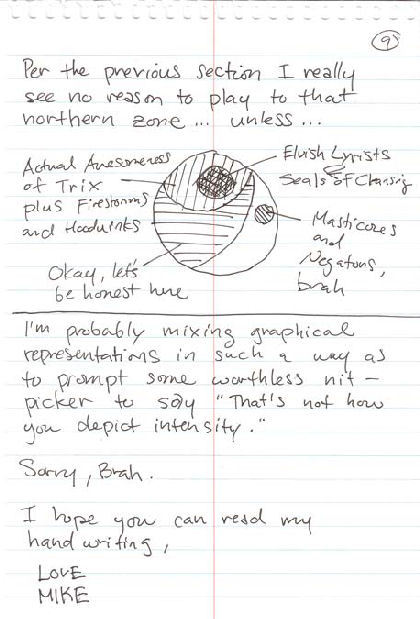

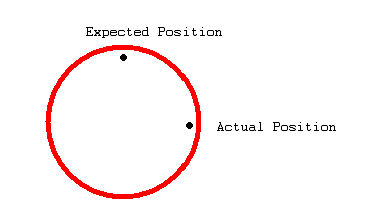

Maybe the directional analogy works better for you like this:

The important thing is that the opponent is aiming for you. This might look like a two-dimensional circle-and-dots built on the coffee dregs of graphic design platforms, but you have to imagine arrows coming at the model from your perspective on high. He is sending those arrows north. He wants you to be up near the Y-axis but you are off to the right on the X-axis in this example; he willfully has no defense there. Part of the reason that you are able to be successful, perhaps with a less powerful deck, is that he is wasting energy flinging poo up high when you aren’t anywhere near there. If you were a less powerful deck — say, a 3 fighting a 10 – and you were both able to agree on the field of battle, you would be in trouble. The secret is riding the opponent’s wasted effort so that you don’t have to work as hard to win.

A nice recent example would be how some of the anti-Flash decks approached Flash at Grand Prix: Columbus. There were different positions that they could take. Some wanted to lock down with Leylines. Others thought that it would be a good idea to play a bunch of small creatures like Meddling Mage, True Believer, and Samurai of the Pale Curtain, to foil the Flash combo in some way or another. This might even have worked against untuned Flash decks. The problem is that the top tables Flash decks all had Massacres and their game plan was to bring them in, often transforming into decks that didn‘t care about Leylines, True Believers, etc.

Regardless of the fact that Massacre – for no mana – can take out your whole force, think about how following a bad strategic path affects your decisions irrespective of the opponent. Will you value a hand with Meddling Mage? What if the hand is otherwise a little weak… but it has both Samurai of the Pale Curtain and True Believer? Are you going to keep there? The problem is that you think that you agreed on a particular field of battle (let’s make this about your kill apparatus, but I’m covering with this 2/2)… and you only got it half right (we’ll agree on your 2/2 all right). It gets worse and worse if you’re also playing for the Leyline and the Flash man has switched kills on you. All of your resources are committed, ostensibly interactively, in that top point of the red circle; however the opponent no longer lives there, if he ever did. You just end up plucking worthless card after worthless card, trying to play a game where there is no legitimate interaction. Why? The motherlover moved out of the way.

Just a caveat: One of the reasons I generally dislike highly linear – if ostensibly powerful – strategies in environments where they are expected is that they can’t really partake in a repositioning for bad matchups if their early game or mana is explicitly tied to the linear. Affinity is an obvious example, being all artifacts – Ancient Grudge doesn’t care if it’s smashing Myr Enforcer or your first lands; it might not be there specifically for the lands, but if opportunity knocks… Go ahead and manascrew some poor dope is what I always say.

A cheat sheet that you can use for thinking about one angle of rebuilding a plan for when you seem to be behind against more powerful cards goes something like this:

Control

Generally beats Board Control

Sometimes beats Combo

Sometimes beats Beatdown

Generally loses to Aggro-Control

Beatdown

Generally loses to Combo

Sometimes beats Control

Generally beats Aggro-Control

Generally loses to Board Control

Combo

Generally beats Board Control

Generally loses to Aggro-Control

Generally beats Beatdown

Sometimes loses to Control

Board Control

Generally loses to Combo

Generally loses to Control

Generally beats Beatdown

Sometimes beats Aggro-Control

Aggro-Control

Generally beats Combo

Generally beats Control

Generally loses to Beatdown

Sometimes loses to Board Control

Like most generalizations in Magic, take this cheat sheet with a grain of salt. There are formats where beatdown hands down beats control, and other formats where the opposite is true.

This is what I mean about demeanor. A lot of how Magic works interactively hinges on how you act, not the cards and the strategies as they are dictated. When I was playtesting Jushi Blue for States last year, I kept finding myself in the same spot against White Weenie and Boros. I was playing the deck like a super counter (like most of you would if the forums ring true), and this wasn’t right at all. I found over the course of many ten-game sets that it was right to immediately tap out for a monster if I could, because my one monster would cost the opponent several cards. I was waiting around for good spots and second chances that were never going to come. The deck was [True] Control, but I decided to play it like a Board Control deck in-context. I tweaked my early game cards to include a “Really?” in Remand (which was not present in the first drafts, or in most other Blue decks of the era) to tempo the opponent early and draw into my Keiga, making sure I actually hit my drops on the way to six. A year later and that has largely become the default strategy for the deck style, with lighter counters more common, and even descendents like Aeon Chronicler falling into the same role.

The Rakdos transformation that Kai Davis used to qualify was built on switching his spot in the matchup. Instead of being a crappier version of the same deck when playing against Gruul (this is actually a spot where Sean’s web will fit, if for no other reason than the decks have the same plan), he morphed into a spot more like The Rock, a little fatter, more board control than supine beatdown, Sedge Slivers, and Tombstalkers.

Remember that the opponent is on a vector and he is also a moving object. If he anticipated your move, you may be subject to his counter-strategy. The B/R switcheroo only works because most Gruul decks look at the typical Rakdos with the idea that they already won and have no sideboard cards. If they start playing a lot of Threatens, Tombstalker ceases to be a trump.

Richard Feldman has written a fair bit recently on “Resilience” and similar concepts, trying to steel decks he likes to weather the power of the opponent’s interaction. I told Richard that I feel that Resilience is actively bad Magic. The problem as I see it is that you are agreeing to play according to the opponent’s rules. Sometimes you don’t actually have a choice (you are a bunch of artifacts and he sideboards Ancient Grudge). Most of the time I see this as less desirable option than trying to define the game in your own terms. I don’t like it because when you agree to the opponent’s terms, something has to go right for you or you can‘t win. He can’t draw his sideboard cards, or no airline lost your luggage, or you drew the nuts, or you didn‘t draw those few vulnerable cards that are still in your deck… Something.

Think about it on the numbers. Really, anyone can get a 6/10 in sideboarded games against known strategies if they want to. If your strategy is to play around insanely powerful and cheap hosers, or to bait them out at known short term losses, you just end up helping any opponent who has thought about trying to beat you. It isn’t hard when you‘re willing to play their game (which is really just them playing your game, sort of), and when you are playing a deck like Ichorid, Affinity, Standard Dredge, etc., that might be really strong but is also known and not difficult to hate out given the available cards in a format. 6/10 might be on the low side of what the other fella’s sideboard can do to you. 7/10 or worse might be your lot (this is usually what I try to shoot for, but it‘s kind of hard to get against Storm decks for the decks that I typically like to play), and you are looking, realistically, at maybe 5/10 matchups all day from basically everyone with any minimal amount of sense over the course of the day. Your graded Game 1 percentage against a field has to be in the 7/10 range – against the field – just to break even. Opponent unknown, you have to be willing to sit down and say “I know you’ve got my number, or at least you can chase ten minutes from now… but screw you buddy, I’m winning this one seven times out of ten, and I don’t care who you think you are,“ every time you sit down. At the end of the day, you need some serious dice to make Top 8… And then you still have to win again (sometimes like three more times).

Last thing on Dredge – the reason that I made such a big deal out of Golgari Brownscale elsewhere recently is that siding it does the exact opposite of playing a Resilience strategy and tries to position the vulnerable Dredge flank with giant life gaining boxing gloves. While not perfect – and a canny opponent can probably figure out what to do there, too – it seemed pretty awesome to me; I’m sure I would have screwed up against this ugly Little Green Man, at least the first couple of times.

LOVE

MIKE