When the post-Misstep post-Innistrad format debuted, for a while Legacy was dominated by flexible blue-based decks and Maverick, a classic midrange deck. With the new year, though, the winds of change have started to blow as far as the top spot is concerned (though the Charlotte-winning Delver deck could arguably be considered flexible again). The last three Opens before Charlotte though were won by extremely linear decks and the Charlotte top eight was full of them. Today I’ll try to explain this phenomenon, as well as talk about options for how one can attempt to fight back the linear offense.

First, I think it’s important to clearly illustrate what a linear deck is (I thought anybody actually playing Legacy would be familiar with this part of Magic theory language, but a lengthy discussion on mtgthesource has lately convinced me of the opposite). So let’s start with that.

What is a Linear Deck?

A lot of people associate a linear deck with the abuse of named mechanics or typelines. Storm, Affinity, different tribal decks, Dredge—those are what people think of when they hear a deck described as linear. While those decks are linear, that doesn’t mean you have a full understanding of what the term means just by looking for this characteristic. Reanimator, Burn, Mono-Green Stompy (think Rogue Elephant and Ghazbán Ogre) and Draw-Go, for example, are decks just as linear as those focusing on breaking named mechanics.

What really decides if a deck falls into the linear category is its strategic focus. If a deck is totally focused on pursuing one single angle of attack or abusing one particular kind of interaction, that is what Magic theory calls a linear deck. Sometimes you might even find a few elements that feel non-linear in a deck that should still be considered linear. That generally happens either because those decks don’t have the tools to fully pursue their linear strategy (Figure of Destiny in Burn, for example—there just aren’t any one-mana burn spells left) or because a slight deviation from the linearity pays incredible dividends (like Emrakul, the Aeons Torn in the Hive Mind deck adding a totally different angle of attack for a measly three slots).

Another mistake many people make when they hear the term linear is to equate it with ease of play and a scarcity of meaningful decisions (or decisions being largely automatic). That is definitely not the case. Sure, some linear decks are comparatively easy to play (Burn will almost always want to maximize damage output by pointing burn at the face while maximizing mana usage, for example—and even then facing Patrick Sullivan is a very different experience from someone who just picked the deck up this morning), but others are among the hardest decks to play correctly in all of Magic (just watch a true master play Storm and compare his decision making to that of a relative newcomer to the archetype).

The Success of the Linears

Now that we know what we’re talking about, it’s time to understand why linear decks are so successful lately. To do that we need to understand what their strengths and weaknesses are—and it’s all related to the definition above.

Linears go all in on one single angle of attack. As mentioned in my article on beating diverse strategies, overloading the opponent’s answers is a very powerful way to punish people for playing flexible decks—and flexible decks still make up a large part of any Legacy field, linears being successful lately or not.

Some linear decks take this approach to the max by making anything that isn’t an answer to their particular angle of attack essentially a dead card. Look at something like Burn, Draw-Go, or Storm

Creatures (13)

Lands (19)

Spells (28)

Sideboard

Draw-Go (not a Legacy deck)

Randy Buehler/Andrew Cuneo

Worlds 1998

Main Deck

18Â Island

4Â Quicksand

4Â Stalking Stones

1Â Rainbow Efreet

4Â Counterspell

4Â Dismiss

2Â Dissipate

3Â Forbid

4Â Force Spike

4Â Impulse

3Â Mana Leak

1Â Memory Lapse

4Â Nevinyrral’s Disk

4Â Whispers of the Muse

Sideboard

2 Capsize

1Â Grindstone

4Â Hydroblast

4Â Sea Sprite

4Â Wasteland

Lands (17)

Spells (43)

If you’re unable to interact on the stack or with cards in hand, the game is going to be extremely non-interactive (if you don’t consider counter every single spell your opponent plays as interactive—and you shouldn’t, really).

It’s even worse against something like Dredge that comes close to ignoring just any form of interaction other than graveyard hate. Cards like Swords to Plowshares or Force of Will may look like they interact with the deck, but in all honesty don’t do very much to deal with it. The only thing that really puts a crimp in the deck’s style is graveyard hate. If you look at last week’s Top 8 (won by Adam Prosak with Dredge), you’ll realize that there definitely is some meaningful interaction present—out of the sideboard, that is. Over all there are:

6 Tormod’s Crypt

1 Bojuka Bog

6 Surgical Extraction

4 Faerie Macabre

8 Leyline of the Void

That’s 25 cards, averaging out to about 3.6 cards for each of the seven decks. That is actually a comparatively high amount of graveyard hate compared to some Top 8s I’ve seen, but if those 3.5 cards are really the only cards that matter in a matchup, things look good for the graveyard abuser. In addition, most of these hate cards aren’t actually game over. They simply weaken Dredge’s linear game plan to a certain extent and slow the deck down, hopefully allowing opponents to race or making usually low value interactions enough to pull it out afterwards.

Now saying everything else doesn’t matter is obviously oversimplifying it. If your hate buys you some time, you might just kill the Dredge player before he really recovers (meaning your cheap creatures definitely do matter—once you’ve already found relevant interaction). In addition there are synergies and interactions from Knight of the Reliquary fetching up that Bojuka Bog (probably too slow if that’s all you do but good enough as the killing blow after buying some time with marginally effective cards like Swords to Plowshares) to Batterskull getting bounced to control Bridge from Below (and being redeployed with Stoneforge Mystic) that give decks some game against it even without dedicated hate. Even Force of Will usually does at least something because it can stop the Dredge player’s first discard outlet, buying a turn. There is also the little matter of the combo decks just winning first even without any disruption.

All that being said, Dredge succeeds really well at blanking most cards in its opponent’s deck, which is why the deck is a force to be reckoned with in the first place.

Virtual card advantage due to blanked cards isn’t the only thing working in favor of linear strategies, though. Going linear usually comes with another great boon: speed. In fact not all linear decks profit from blanking opposing interaction (just look at Affinity or all of the tribal decks for examples that largely play easy to interact with threats). In those cases their reason to go linear is usually that they can do things much earlier than they’re supposed to be done.

(Note that this isn’t an either or kind of deal. Dredge and Storm, for example, both blank most interaction and can routinely win by turn three undisrupted.)

By giving you tempo (because that’s what speed usually comes down to in Magic), a lot of possible ways to interact with the linear deck just fall by the wayside even if they’re in theory available either because they cost too much or because there isn’t time to draw into them without excessive mulliganing. In the article I already linked to above, I called this approach outrunning and mentioned it as another way to overcome less single-minded adversaries.

Sometimes there is also something less tangible to consider: raw power. While Goblins, for example, can have blisteringly fast starts on the back of Goblin Lackey, its real strength lies in getting to run absolutely ridiculous spells. A 2/2 haste Fact or Fiction and a 1/1 Demonic Tutor as well as a cantripping Incinerate and your personal Helm of Awakening are all good reasons to decide to focus exclusively on Goblins to get the job done, even if it means being interactive and not especially fast. And running 30+ creatures is still a pretty good way to overload opposing defenses, by the way.

What it all comes down to is that the linear decks we see succeeding are by their very nature ideally suited to prey on a metagame full of diverse strategies that prepare more for other diverse strategies than for linear decks.

Knowing this, just take a look at the decks occupying the Top 16s and feature matches on both the StarCityGames.com Open Series and most other tournaments—exactly, there are a ton of Canadian Threshold (aka RUG Delver), UW Stoneblade, and Maverick decks, among a multitude of other flexible decks that try to be interactive: perfect prey for correctly chosen linear strategies.

The Costs of Going Linear

So if going linear allows you to create virtual card advantage by blanking opposing cards and also coincides with significant tempo-advantages, why aren’t we all playing linear decks all the time? Because going linear also comes with significant costs, obviously.

Firstly, by being single-minded these decks themselves are often unable to interact in significant ways with other strategies (or particular cards) and if the opponent’s game plan simply trumps theirs, they’re looking very bad indeed. Reanimator and TES are two examples of linear decks that are usually significantly favored against other linear strategies due to the speed with which they can implement their own game plans. (Their troubles usually come against the more interactive diverse strategies—which should explain why we see a fair mix of linears succeeding, by the way. Some are preying on the diverse strategies; others feed on their own kind). You could do much worse than picking up one of these decks if you expect the metagame to be overrun with strong linears.

The other cost of being linear is what most people think of in the first place when they think of linear strategies—you open yourself up to getting devastated by specialized hate. I mean how does Affinity beat a turn two Null Rod? How does Storm win with Ethersworn Canonist in play? What exactly is Dredge supposed to do when the opponent starts the game with a couple of Leyline of the Void in play? Does Burn really beat Circle of Protection: Red in more than a handful of games?

The point here is that it’s definitely possible to beat linears if you want to. Yes, all of those decks can in theory get out from under the hate. The likelihood of that happening is sufficiently low to shift the game very much in their opponent’s favor, whatever else they might be up to doing, though. The question as always is this: is trying to hate the linears worth it?

I’d suggest that right now the answer to the first question is a resounding yes. That leaves us with a different problem, though: the tiny issue that different linears often demand very different forms of hate.

As it is, we’re not seeing the resurgence of one single linear strategy but rather a combination of very different types of linear strategies. That’s one of the dangers of a wide-open format with dozens of different high power linear strategies—there will always be some kind of linear people simply aren’t really ready for.

You can try though, and that’s what it looks like we should be doing right now. Even if we only look at the last four StarCityGames.com Open Top 8s (a very limited sample), we can already see thirteen(!) different linear strategies. Think about it. Out of 32 possible different decks, more than a third of that number is already taken up by different linears—without figuring in repeat appearances:

Burn

Affinity

Dredge

Goblins

Reanimator

TES

Ad Nauseam

B/G-Loam Control (labeled as Lands but actually quite different)

Elves

Sneak and Show

Enchantress

High Tide

Painter

Beating Linears

How do you try to beat all of those many different strategies? I already mentioned that it’s possible to simply play your own linear deck that is especially powerful against the other linears and beat them at their own game. If that isn’t your cup of tea, though, there are other options.

First, you can try to play something that attacks an element that even linear decks share with other magic decks—like mana or spells—by running something like Stifle-based tempo decks or Pox and shoring up particular weaknesses with dedicated hate at the expense of cards against more diverse strategies (in the case of Canadian Thresh a mix of Pyroclasm, Ancient Grudge, and graveyard hate should usually do the trick for example).

The problem with this approach is that the linear strategies that actually succeed at the moment are largely immune to those decks’ mana denial plans. Most of them can pretty much ignore Wasteland and a lot of them don’t even care much about the Stifle plan (which is, I think, a big part of the reason why exactly those linear strategies are the ones succeeding—just look at how much Canadian Thresh appears in every Open Top 16).

Taking Down the Big Bad Wolf with Special Ammunition

Hate cards—and silver bullets in particular—are the classic answer to powerful linears. The problem right now is that just jamming the correct hate for one or two decks into your sideboard isn’t going to help you deal with all the others.

One solution to this problem is to use Tutor-based silver bullet sideboards instead of running multiple copies of the actual silver bullets themselves. By playing a set of tutors you make for hate of all shapes and forms while retaining the ability to find it when needed.

The poster child of this approach is Maverick using Enlightened Tutor in its sideboard as well as Knight of the Reliquary and Green Sun’s Zenith in the main deck to provide answers for specific problems when needed. David Gearhart’s Shot in the Dark  similarly uses a full set of Enlightened Tutors between main deck and sideboard to prepare for just about any contingency. The success of these decks is, I think, a telling sign as to the viability of this approach.

Because these decks already illustrate how to use Enlightened Tutor and Green Sun’s Zenith in this capacity, it seems somewhat superfluous for me to cover these approaches in depth. You guys probably know how to look up deck lists already and can think of a bullet or two on your own. Instead I’d like to provide you with a few more unusual options that I think could do with being explored.

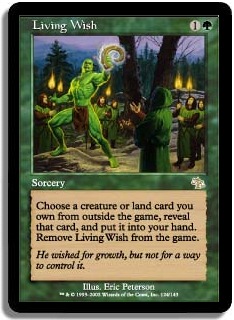

Starting with something that saw some play during the Misstep era in the Dark Depths Junk decks but has vanished since, let’s take a look at Living Wish. Just imagine this:

Main deck:

4 Living Wish

Green, White, and Black mana

Sideboard:

The Tabernacle at Pendrell Vale

Yixlid Jailer

Bojuka Bog/Faerie Macabre

Ethersworn Canonist/Thalia, Guardian of Thraben

Kataki, War’s Wage

Kor Firewalker

Phyrexian Metamorph

Phyrexian Revoker

Devout Witness/Nova Cleric

Now, to run with this you would likely need a good reason to want to have a bunch of Living Wishes in your main deck and sacrifice a few additional slots to make room for targets against more flexible decks (tarmogoyf and Thrun, the Last Troll probably) but it certainly is powerful. All Wishes are actually especially sweet against linear strategies because they allow you to deploy hate in game one before the linear deck has the opportunity to adapt with its anti-hate.

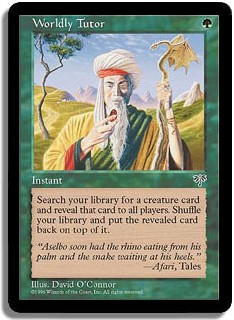

Sticking with the creatures for a moment—I’ll cover the other viable Wishes soon, I promise—a similar package could be the foundation for a Worldly Tutor sideboard similar to the Enlightened Tutor ones already in use. For a deck like Zoo that is already pretty solid against most things that aren’t fast linears, something like this might do the trick:

3 Worldly Tutor

Faerie Macabre

Scavenging Ooze

Gaddock Teeg

Thalia, Guardian of Thraben

Kor Firewalker

Phyrexian Revoker

Nova Cleric

Intrepid Hero

Phyrexian Metamorph

Why wouldn’t Zoo, which is white, not simply use Maverick’s Enlightened Tutor approach? Worldly Tutors simply are much better at advancing your game plan when you already have your hate down, not to mention the hate suddenly actively helps end the game. This is a quite valuable effect to have as playing against linear decks often comes down to mulliganing to hate, meaning your regular game plan can be severely impaired.

Other options for these creature-based Tutor boards include the obvious Qasali Pridemage, Trygon Predator, and Shriekmaw, as well as a million techy options left to explore in the vast card pool of Legacy.Â

It’s not all in green and white, though. The other two reasonably costing Wishes also have some nice options to offer. Burning Wish with a basic package of:

Morningtide

Shattering Spree

Paraselene / Reverent Silence

Firespout

This seems rather impressive as long as you can already deal with the stack-based decks. These four cards already allow you to answer a significant amount of the linear decks we see popping up and depending on your colors you get other goodies like Extract (take that U/B ANT) or Innocent Blood (nice Show and Tell). Aside from providing hate, Burning Wish also allows you to play very powerful threats without overloading your main deck with them. I think this card should see more use outside of dedicated combo decks with all those linears running around.

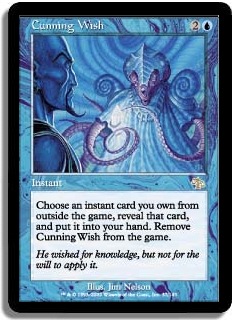

One toolbox I’ve personally used multiple times (in CAB Jace, for example) is Cunning Wish. Three mana can be a little slow when it’s your main line of defense, but having a few means to interact in places you usually can’t goes a long way, especially in a blue deck that should already be reasonably well set up to slow down the opponent’s offense.Â

Some of my favorite tools to get your creative juices flowing:

Ravenous Trap

Surgical Extraction

Wing Shards

Diabolic Edict

Volcanic Fallout

Mindbreak Trap (and all kinds of counter magic in general)

Hurkyl’s Recall

Shattering Pulse

Pulse of the Fields

Samite Ministrations

Tsabo’s Decree

Allay

Back to Nature

Fracturing Gust

Tempest of Light

Succeeding Without Summer School

If you aren’t ready to fill your sideboard with Tutors and bullets (or if your deck’s colors preclude you from using that approach efficiently), you can at least maximize your chances by using overlapping hate. Instead of just taking whatever kills one linear, choose options that cover a multitude of angles even if they’re slightly weaker against each opponent. Sure Null Rod isn’t the best card against Storm, but it often does quite a number on them and just so happens to totally ruin Affinity. Imagine a sideboard along these lines:

1 Null Rod

1 Thorn of Amethyst

1 Sphere of Resistance

1 Chalice of the Void

1 Pithing Needle

1 Phyrexian Revoker

1 Surgical Extraction

1 Faerie Macabre

1 Grafdigger’s Cage

1 Relic of Progenitus

1 Tormod’s Crypt

1 Engineered Explosives

1 Sword of War and Peace

1 Umezawa’s Jitte

These are intentionally all colorless options (and therefore light on ways to deal with Enchantress) to show you something that isn’t color-bound. Once you dip into colored options like Thalia, Guardian of Thraben, Ethersworn Canonist, Gaddock Teeg, Choke, Thoughtseize, and all four Blasts, among many others, you will have a number of effective cards to bring in against just about any type of linear strategy.

Sure you won’t suddenly turn matchups into total blow outs whenever you draw your sideboard card, but if your deck already has a fighting chance game one and you aren’t particularly good at reading the metagame, trying something like this can be an excellent way to shore up a multitude of possible matchups all at once (and no, you obviously don’t have to dedicate your whole sideboard to this approach the way the above one does).

Scattershot

An extension of this strategy of overlapping sideboard cards is to use cards that allow you to simply extend the range of your interactive capabilities. These cards won’t beat a linear deck almost on their own like classic hate would. Instead they allow you to sideboard a significant amount of additional defense against just about everything you might run into. When using this kind of strategy you don’t expect any single card to beat them, you simply give yourself a ton of different ways to interact when before you couldn’t.

One of my favorites, Engineered Explosives, isn’t insane against Dredge in any way. Playing one for zero will generally be good enough to buy you a turn or two, though. Similarly, Chalice of the Void for zero won’t stop Affinity. Turn one on the play, though, it will likely slow them down enough to become much more manageable.

Broad answers like Ensnaring Bridge, Moat, and Peacekeeper similarly won’t usually lock up the game on their own. Combined with all those other cards your linear opponent suddenly has to interact with, though, and they can be the difference between winning and losing to the threat before you.

I think this line of thinking is one of the big reasons Surgical Extraction sees as much play as it does. Yes, it’s reasonable graveyard hate (especially against Reanimator) but can also come in to replace useless main deck cards against decks ranging from High Tide (try to get the Tide or their own protection) and Storm (if they expose an Infernal Tutor/your discard does, winning suddenly becomes a lot harder for them) to anything with Intuition and even other control decks (getting their Jaces is actually quite good, though I would never take out an actual good card for it).

Leyline of Sanctity is another card that isn’t the best against anybody (High Tide and Tendrils decks can still draw a million cards to win through it and Burn does have ways to deal damage that don’t target), but it buys time against a wide variety of opponents (did you know Intuition targets?) and has additional applications against heavy discard. If what you take out for it simply doesn’t do anything in the matchup at hand, getting something that is at least mildly annoying for your opponent is already a big improvement.

When you’re using this kind of approach to beating linears you aren’t looking for haymakers but to employ the strategy of death by a thousand tiny stings. Nothing you do will stop them completely but almost everything you do will restrict their options somewhat—essentially you’re turning an originally non-interactive matchup into an interactive one.

The problem with this? Interactive matchups are much easier to lose than blowout matchups. By going there you allow for linear strategies to still be able to beat you even after you adapted your plans, which means the linears will still succeed a significant amount of the time and remain a powerful player in the metagame. But that’s as it should be. A wide-open format also means one in which linears flourish, not only diverse strategies.

End of the Line

Now these approaches aren’t the best ideas in a field heavy on one particular linear. If the field looks like current Legacy, though, having a shot against every linear might be worth more than soundly beating some and losing to others.

Linear decks are here to stay; I have no doubt about that. Those strategies are very powerful and neuter many opposing cards before the game has even started. They’re far from unbeatable, though. Actually, as shown above, particular linears are much easier to fight than flexible decks as long as there is a clear target to aim one’s hate at. This is the kind of situation that allows those players skilled at metagaming to excel.

But even if you don’t have the time or knowledge to correctly divine the linear flavor of the day, there are ways for you to make the games at least close fights instead of one-sided slaughters. And that’s what we all want out of Magic, after all: exciting games, the rush of adrenaline, and hanging on by our nails to weather the storm. If there was a way to easily beat anything and everything we run into, this game would soon be boring after all.

That’s it for today. If you’d like to share your own ideas as to how to deal with linears or think I’m totally off my rocker, let me know in the comments. Until next time, make sure you know how to derail an object that’s moving on a straight line!

Carsten Kötter

Bonus Section: For the Attention of Wizards R’n’D

I’d like to take the time here to address something I heard out of R’n’D lately—sadly I’m not sure where I heard it (maybe during PT Dark Ascension coverage?), so I can’t provide you with an exact quote or a source. The gist of it was that giving Dredge Faithless Looting was fine in R’n’D’s opinion because decks that interact only on unusual axes like Dredge win and lose anyway depending on the presence of dedicated hate. As long as people play enough hate, those decks are a bad choice and will die off, at which point the hate leaves sideboards and those decks become great choices again.

While I agree with the general sentiment that hate should be used to keep strong linears in check, there is a limit to how much hate can do. Once linear decks reach a power level like Vintage Dredge where it really is only the hate that matters (note that the following is only my personal opinion), games degrade to mulliganing straight into the hate and sideboards need to overload on hate to make that possible. At that point players are unable to prepare for much else. Vintage sideboards at the moment generally contain at least six cards against Dredge and a similar number of cards against Workshop prison strategies. For now that works, but what happens if another, similarly powerful linear deck is born? How about another two? There is a point at which gameplay breaks down and tournament results start to depend on how the pairing software treats you on that particular day. Not a great experience.Â

As far as Legacy is concerned, it is at the moment distinctly possible (if unlikely) for decks not geared to do so to beat Dredge or Storm game one without the unfair decks mulliganing into oblivion. Sometimes Zoo or Burn just races them. Sometimes the control deck just finds its Swords to Plowshares and Snapcaster Mages early enough to keep Dredge’s Narcomoeba and Ichorid off the table until the dancing Batterskull is assembled and ruins their Bridge endgame. As long as that is the case, the hate doesn’t need to be overwhelming; it just needs to reinforce these main deck game plans to the point of shifting the matchup significantly.

As long as R’n’D believes hate is enough to keep linear strategies that interact on unusual axes in check, cards like Faithless Looting will keep seeing print. Generally speaking, this is a good thing. We want to see change in every part of the metagame over time. The problem with cards being added to the linears is that at some point their original game plan becomes strong enough to truly ignore everything but cards tailor made to beat them. By reducing the viability of the more incidental ways of beating a non-interactive strategy because its power level rises, we are bound to reach a point where only massive dedicated hate works.

At that point mulliganing straight into the hate also becomes more important because fewer and fewer normal hands are likely to get there or will be able to buy the time to naturally find the hate. That, in turn, leads to more and more sideboard slots needing to be dedicated to specialized hate, which opens up a whole can of worms from other parts of the metagame that suddenly can’t be addressed any more.

As long as the number of viable strategies is low, this is a situation people can deal with. In a format with as many widely different decks as there are in Legacy, though, problems would be sure to abound.

At that point we’re looking at another use of the ban-hammer to fix a skewed format, something I personally hate to see happen, especially if it eliminates a whole archetype (even if it’s something I personally dislike playing against as much as Dredge—and make no mistake if Looting Dredge should prove to strong they won’t ban looting; they’ll hit a more central card. Just remember what happened to Survival).

There are fans of the archetype and they shouldn’t be screwed over because R’n’D dismissed concerns about what a card might do to a deck because, "That deck needed to be hated anyway." Even against decks that need to be hated, the question, "How much hate is necessary to consistently beat them?" is of critical importance.

Note that it doesn’t feel like we’re at that point yet with Legacy Dredge, but hopefully someone from R’n’D will read this and they’ll consider this kind of problem when deciding if a card is worth printing. Much like the difference between bad and worse, needing hate and needing hate are two very different things.Â