I’ve been thinking about the complexities of Commander a lot lately, far more even than I’ve been playing it. Much of my Magic in recent weeks has been focusing on drafting Gatecrash on Magic Online, which I now learned was for no specific purpose, with the MOCS tournament I was hoping to qualify starting at 6 PM on a Saturday evening and finishing by dawn the next day if I were lucky, leaving me to wonder why I keep aiming at events with clearly published schedules without looking at the schedule first.

I’ve also been working on a sweet, sweet Modern deck, and my distraction in the latter case has recently been justified by results—Drew Levin wrote an article last week about losing in the finals with Grixis Delver, but he wasn’t the only StarCityGames.com writer to make it to the finals of a PTQ that weekend. However, this article is not that article; I’ll post the decklist at the end of the article, but Dear Azami is about Commander and we shall stay on topic.

I guess you could say what has me thinking about Commander lately is the intricate complexities of different types of communities interacting and what happens when it tries to go competitive. Bennie Smith article last Friday went into significant depth about the clash between casual play and competitive play on the eve of an awesome sounding Commander tournament being run at Richmond Comix for a shiny, expensive prize. He surmised that he would aim to play the role of regulator for the tournament to try to advocate for a style of play he summarized in a quote short enough to tweet:

“When choosing cards for your deck, ask yourself—is this card interesting and novel? Would I have nearly as much fun losing to this card as I would winning with it?”

Regulation is the heart and soul of the predicament we face as we mix and blend the casual and the competitive. Perhaps my perspective here is skewed by the depth of intensive and hands-on research I have done in the last year and a half on this matter, both in broad strokes and in actual usage. Just as likely is the fact that I am waxing nostalgic because the long-term houseguest I have been putting up in my apartment has finally moved out to go back to her life before Occupy Wall Street, for me at least decisively concluding the end to any participation in that group since it no longer seems to be active.

I spent some thirteen months with Occupy Wall Street as the oddest ill-fitting duck of a peculiar bunch—the one who came to the proto-anarchist, supposedly anti-capitalist movement to teach “The Movement” that they were for this thing their street chants and protest placards claimed to be against, to enlighten them as to the difference between capitalism (as a system of human interactions) and crony capitalism (the root of the problem we currently face worldwide).

StarCityGames.com is not a political site. I’m not here to argue depths and details over the financial crisis of 2008 and the decade of details leading up to that awful conflux of events. But as a “political” animal, I tend towards the camp of libertarianism as the nearest approximate label that is commonly understood as something which approximates my understanding of the system of the world and my moral worldview. And as the blunt summary of political camps go, libertarians hate regulation.

Why, then, do I want to talk about regulation and Commander? Because Commander is a unicorn among Magic formats. It began as a community-driven format, growing deep community roots as it grew broader and more people learned about it back in the days when we still called it Elder Dragon Highlander because there were Elder Dragons involved. There are many formats of Magic you can play, but Commander is unique in that it has the broadly accepted staying power of an “official” format like Legacy, Modern, Standard, or Vintage as well as the support from Wizards that “official” formats get (like Pauper, you can play it as an actual format on Magic Online) but without the regulatory controls that come from Wizards of the Coast as the official central body.

Instead, we have the Rules Committee, overseen by Sheldon Menery and a small cabal of central decision-makers that follow a fairly strict process for determining what is and what is not Commander.

This is the first format to come from outside of Wizards of the Coast and achieve broad support while retaining this type of external decision-making body, and it retains its unique character accordingly. It is highly responsive to the community that plays it, with every confidence that the people who regulate the format are of the same mind as everyone else as to what is fun and what ruins others’ fun because in theory any player could be of the Rules Committee. You don’t need to be an employee of Wizards of the Coast, and in fact, unless I’ve missed something, none are.

What I learned more than anything else from Occupy Wall Street is their peculiar brand of decision-making called consensus. As a formal process, it is tedious, following Robert’s Rules of Order more than anything else, and as a formal process, it was doomed to failure. There has been much criticism of that decision-making process within the group for its tendency to expose the majority to fiat rule by an obstructionist minority. If the recent political battles over the debt ceiling and the sequester seemed tense and bloody, remember that this is still more-or-less the interaction of two equally-sized parties vying for control over the direction of governance; in the decision-making deliberations of Occupy Wall Street, a mere 10% of the room (plus one person) were entirely capable of stopping forward progress in any direction and for any whim.

As a concept for decision-making, it is powerful and empowering: with each individual participating in a decision holding full veto capacity, more work must go into making decisions because you have to have something 100% of the people can live with, not something that makes 50% plus one happy. It was slow and plodding, even maddening at times, but it forced the obstacle of actual human interaction on the group as a whole in order to find better answers and make better decisions. Decisions could even be made without a single conversation at all: if everyone knew what the right thing to do was, they would all just do it rather than have a meeting to talk about it.

Of course, they loved to talk. I have been to meetings to talk about having a meeting, and at one hilarious low point I was involved in a conversation about planning a meeting to plan a meeting. Suffice it to say I don’t want to remember that and certainly don’t want to talk about it.

Commander has unique characteristics among Magic formats, such as its unique customizability for your local playgroup and the broadly distributed decision-making process that goes into Rules Committee decisions. If your group of players doesn’t like losing to extra-turn effects, they can just ban all of the cards that let people take extra turns, and it’s a short enough list that is clear enough in fundamental concept that you can do it easily with no feelings hurt. If your playgroup doesn’t like the fact that one of their favorite cards is banned, that’s fine too because what everyone in the group agrees on is, for Commander, what the rules are.

Thus I bring up the concept of consensus because Commander is a consensus-driven format. The Rules Committee recently unbanned a card in exactly that fashion, after Sheldon Menery playgroup at Armada Games did a test run with Kokusho, the Evening Star unbanned (but not eligible to be played as a commander); the data from this weeks-long series of semi-competitive games was enough to sway the Rules Committee to free Kokusho from a years-long banning.

And much like my experiences with Occupy Wall Street, the decision-making process is equally accessible the other way around, too—consensus-building around something that needs to be addressed can lead to a banning even if the person building that consensus is outside of the Rules Committee, even if that person never had a single conversation with a single member of the Rules Committee about it. (You may remember this as my long-standing efforts to put the ban spotlight on Ad Nauseam in Commander, which adopted Griselbrand the first moment it was possible to do so and which led to Griselbrand’s banning immediately. Still waiting on Ad Nauseam to get the boot, though…)

We as a community have butted up against the competitive-cooperative dichotomy more than once, and every time we do, the question of regulation comes up. The dangers to this is that Commander is at its central core a self-regulatory format: you could break it in a heartbeat without even trying if you wanted to. The magic “regulation” comes from teaching the player that they do not want to, and where there are no internal constraints that grow with that self-realization there is the simplest regulatory function of all: if you’re not playing as you ought to be, the people you play with will decline to consent to be so treated. All you need is a brain, a deck, and some friends…and without those friends, you cannot play Magic at all, so you had better color within the lines or else.

If you’ve ever been the first person attacked to death multiple games in a row just because your commander was Azami or Memnarch, you have experienced the essence of Commander’s self-regulatory function every time you lost that last life point. Every interaction you have with a group of people tells the story of your deck, as you all play cooperatively within these at times unclear boundaries to create a beautiful game worth playing where the goal is to have fun along the way, not just win the game. The regulatory function of casual Commander is reputation, both your reputation as a player (i.e., the cards you like to include and how you like to win) and the reputation of your deck (that deck is evil, kill it with fire).

How, then, can we ever compete if competition by its fundamental nature drives a wedge between the purpose of the format and the purpose of your participation in such a tournament?

Consensus and Power Dynamics

The crux of the issue comes from the fact that we are taking a cooperative format—Commander—and turning it against that cooperative dichotomy into a competitive beast. People who “color within the lines” when playing Commander are cooperating in exhibiting the level of self-restraint that comes from the boundaries of just playing for fun and have built their deck accordingly for this cooperative experience. And everyone knows it just by playing with them because if they’re aiming to play an unfun game, that fact will carry forward with them in the future.

Commander playgroups learn from group experiences, and this means identifying where the boundaries are and playing within them. If Commander was a format about just playing the best cards, always and forevermore, this column wouldn’t exist. Dear Azami was envisioned as an advice column for Commander decks, after all, and if the advice was always just play the best things, dummy then I wouldn’t be a very popular advice columnist and this would have been a very bland, short-lived series.

The secret to tournament success year in and year out is to play as many of the best cards as possible in as good a deck as possible, which is how we saw combinations like Necropotence + Force of Will take over the tournament scene for as long as the “Trix” combo deck did. Competing asks us to look at the hard lines boxing in the format rather than the soft ethical lines that spider web within the format, and when these two different dichotomies mix, it looks as if the people who are being cooperative are helping the people who are competing to win.

Like lambs before the wolf, the cooperative players have willfully and knowingly chosen a deck that cannot compete with the most highly competitive monster you could envision, and all you have to do to win the tournament is be that one step more ruthless in your willingness to cut through these soft ethical boundaries in order to obtain victory and the prize.

Ethical boundaries are not legal boundaries, after all, and besides the concept of the spirit of the format we have just the Commander banned list to dictate fair play. It is very stark, with minimal contrast. It is either black or white, with no shades of gray save if a legendary creature is deemed too good to be a Commander and allowed to be played within one’s deck but not at the helm of it. This is where the concept of regulating the behavior of tournament competitors comes in—the banned list is not sufficient to rein in the hyper-competitors without being a list as long as your arm and worthless besides because there are more two-card or three-card combos just waiting to be found and exploited.

No matter how long the list gets, it will stop being wieldy long before it runs out of things you can prove need to be put on it if you try to jam it as hard as you can; if there is benefit to be gained in pursuit of a reasonable prize, these values will be innovated by creative people who want to chase that prize, as you can see in Modern with the unexpected midseason shift of “the Infect deck” into “the Slippery Bogle deck,” choosing the same fundamentally exploitable concept on a different vector because there was advantage to be found in so doing. Is it a stretch to think that with every Magic card in existence able to be played with you can break things if you try?

Can you play Commander—actual Commander—in a tournament setting? The discord between the cooperative play dynamic of a Commander game and the competitive play dynamic of a tournament suggests no, and the first efforts to do something in that vein—the French two-player Commander format—only achieves something like functional play through an extensive banned list and narrowing the play to two players, making it a very different animal indeed from what we think of as Commander.

If you add an extensive ban list, not only would it “not be Commander anymore,” it wouldn’t even help because the next-best terrible thing you can do to people is still a pretty terrible thing to do to people.

Bennie’s article last Friday coupled his analysis with an effective regulatory concept—adding an additional prize to be earned via playing Commander “as it was meant to be played” without addressing the exploitability of such a prize payout system for a tournament because his was an unofficial prize to be given once, so the yawning abyss of collusion and warping the game out of shape via repetition is not really considered.

I can envision two things, however, which can change the cooperative-competitive power dynamic without breaking the Commander format as it was intended just by bringing it into a tournament-play dynamic. One is something that can be incorporated into the tournament structure—a catch-up mechanism—and the other is something that can be incorporated into the deckbuilding rules—a shade of gray between “banned” and “unbanned.” By altering the dynamics of power interactions, you can alter the nature of the interactions you wish to sculpt, and better yet, one of these two solutions can involve broad community involvement and fluctuating consensus on what is and is not allowed over time while also being clear and accessible for use.

Both ideas borrow from other games because I am a giant nerd and have played almost every card game I’ve ever come across at least once. (But not Yu-Gi-Oh! or Pokemon because I am an adult.) Before you hold your nose at the fact that my Magic deck boxes sit next to a Shadowfist deck and Vampire: The Eternal Struggle deck, I direct you to the best tournament report of all time (hint: it’s not about Magic). Read that, get a smile, and then judge me.

Tournament Structure

In Magic, you play one opponent in a best-of-three match, and the means to achieving victory is simple and straightforward. In Commander, you don’t have one opponent, and it is in fact entirely possible to sit there, never play a land or a spell, discard the entire game, never own a permanent…and win the game because the other three players fighting ignore you and nuke themselves into oblivion simultaneously to achieve mutually assured destruction. As the last player standing, do you win?

Some efforts to address this puzzling possibility attempt to ascribe a point value to accomplishments, most notably detailed in Sheldon Menery long-running chronicles of Armada Games’ Commander League Point System. If you have these be cumulative over the course of an event, you run into the problem of people “farming” points rather than competing for the table win, so realistically for an event that is supposed to have anything like a Swiss structure, any point system would need to convert to a table win and thus a Swiss point system (three for a win, one for a draw, none for a loss—or something similar in concept if not exact point values) rather than accumulating, lest collusion be an extremely valid concern.

In actual practice, “what the point system is” has to be part of a group’s decision-making process because woe be the day that a newbie comes with a well-built deck totally ready to kick people’s butts only to find out that the metrics for victory were far different than he expected and that he has in fact lost while clearly and decisively kicking three asses. There doesn’t need to be one at all, in fact, if one victory point were assigned to one player and were awarded to your tally when you successfully oust a player from the game.

If you kill one person and are the last player standing, you have two victory points: your own for not dying and the one you got for killing one of your three opponents. This could be a draw if the person you killed were responsible for killing the other two opponents, and that sounds like a typical outcome in a game of Commander since it is often a very good idea to aim to be second best over the course of an entire game… The first best (i.e., the player who is “obviously winning”) tends to run into a lot more resistance and be targeted the most, and plenty of the games I play aim to survive the “obviously winning” player’s efforts and kill him when we’re alone.

Or, instead of needing to convert to a Swiss system of all-or-nothing, you can simply have these victory points be Swiss points as well, giving a consolation prize to the person who kills one player before dying themselves rather than calling them a “loser” and giving them zero points for their effort. There is a beautiful simplicity to this idea, and as it generates a meaningful spectrum of values over the course of play, I would consider it ideal.

As a fundamental concept for a tournament structure, I would aim to make the tournament rounds broad enough to create a meaningful contrast between the players and then cut to a Top 16 that then selects the final table rather than cutting directly to a Top 4. The final round is a catch-up mechanism that is needed to have a satisfying outcome, alongside the fact that with such a point system and tournament structure you would see plenty of people able to “make the cut” despite playing three games and only “winning” one of them.

In actual practice, this doesn’t solve the problem of hard rules versus soft rules that is central to the core of what Commander is, so while this is a good idea for how to actually run a Commander tournament if that were a thing you wanted to do, it doesn’t solve the problem of tournament-caliber Commander not being played with decks people would recognize to be valid, fair Commander decks. This is the gooey mess at the center of the regulation issue at hand, and as it is centrally derived from the opinions of the community as a whole, it must involve the community as a whole—be it the community worldwide or just the community of players who will be playing in the event.

Everything Has a Price

As the problem with cards being legal but not okay is highly contextual, a matter of opinion rather than a matter of rules, the repair that is needed is to make that which is implicit into something that is instead explicit.

What got me thinking along these lines actually is the continued well-being of Vintage tournaments that allow proxies. Everything has a price—Black Lotus is one hell of an expensive card, after all—but competitive Vintage is surprisingly more affordable when you’re given wild cards you can use to fill these expensive slots. Four slots for Bazaar of Baghdad and suddenly you’re rocking Dredge at the highest levels of competitive play with a deck that is otherwise easy to acquire and surprisingly affordable if that’s what you want to do.

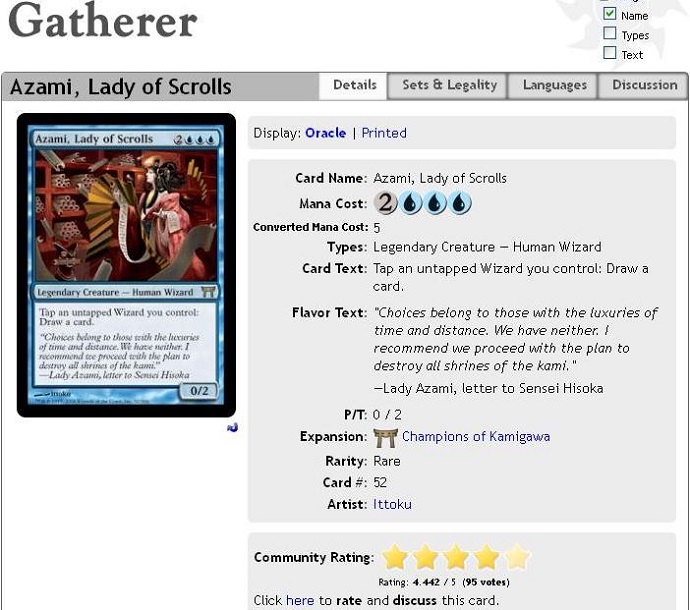

Some cards are on the Commander banned list because of their price more than anything else—the format needs to be kept accessible to a wide range of players, and it’s a hard sell to argue that Mana Crypt and Mana Drain aren’t broken but Mox Emerald is. So I got to thinking about prices, and poking through Gatherer showed me a potential avenue for Commander players to share information and opinions in a process akin to participatory budgeting.

All the relevant info you need is there to figure out what the card does, as is a star-based rating system for how well the community at large likes the card, giving Azami a very high score of 4.42 out of a possible five. This is done naturally and automatically and has been compiled as a statistic over time with a broad player base weighing how they feel about the card as a whole. An identical technological and social-interaction hurdle exists if we wanted to invent a new metric, Commander deckbuilding cost, as a means to say in short that while this card is not banned, we’re not totally okay with you playing it alongside whatever else you feel like.

Tooth and Nail for Kiki-Jiki, the Mirror Breaker and Deceiver Exarch gets really boring really fast, after all, and being able to spend one of eight or ten Tutors to find Tooth and Nail and make it uncounterable via Boseiju or Overmaster is clearly on the wrong side of things despite being clearly legal. All that needs to be applied is a price to play—a points system attached to cards, just as it is to Warhammer miniatures. And just like Warhammer miniatures, you can agree to compete on different levels of playing fields in an easily comprehensible fashion just by saying “I’m playing within point budget X.”

This isn’t quite how we do things in Magic—we have yes/no binaries based on a card’s brokenness. And while we do have different playing fields upon which you can compete, the cutoffs are determined by card age rather than baseline power and interactive synergy. But it is how things are done, to some degree at least, in Commander. Note the recent (and growing) trend to cut Tutor cards from people’s decks, as being more consistent is on the wane and people are favoring playing more diverse games with the same deck instead of just favoring always winning.

If this were an Occupy Wall Street effort to build group consensus in a grassroots way, I’d expect to find a Twitter hashtag for this—#NoTutors—but the Commander community isn’t actively trying to build opinion around this in any meaningful way. After all, each Commander community focuses on the people they play with in their immediate environs, meaning you tell someone “no Tutors” instead of tweet at someone #NoTutors. They’re in the room, sending them a Tweet instead of opening your mouth would just be weird.

We don’t object to Ashnod’s Altar—clearly, if we did, it would be banned. We do, however, have problems with the kinds of decks that want to run Ashnod’s Altar or any similar resource-conversion card that exchanges X for Y at an easy and attractive rate because they are combo enablers and that’s how you kill entire tables of people just by assembling your conversion engine of doom. It happening once in a while is fine, too, so the use of a points system can put a significant deckbuilding price on your Ashnod’s Altar, the cards that combo with it, and the cards that enable you to find individual pieces more easily.

Let’s tag your Sol Ring, Sensei’s Divining Top, Demonic Tutor, Vampiric Tutor, Increasing Ambitions, and Enlightened Tutor with a cost to put in your deck and see how often you achieve a combo kill condition and how sturdy or fragile that combo is when actively being attacked and negated. You can play all of these things, but maybe you can’t play all of them and everything else. Using the community’s interaction as a whole to set opportunity costs on individual cards is an effective means of inducing an individual who is playing competitively to still work within the boundaries of self-regulation because they only get so many deckbuilding points to work with.

The price of most cards would be zero. I added Island Fish Jasconius to the last deck I worked on, and I don’t think it’s going to be breaking the format anytime soon. But I imagine if such a database were created, it would be dynamic, changing over time, and able to effectively point out where the real boundaries of Commander lie in a concrete rather than abstract way. Spider webs don’t stop people nearly as effectively as hard boundaries do, after all. And it would allow for communities large and small to interact in a participatory way while also inviting people to play whatever they want and in a way that is ultimately on the correct side of fair without needing to be monitored by some final arbiter of fairness.

Nobody wants there to have to be Fun Police, after all.

Want to submit a deck for consideration to Dear Azami? We’re always accepting deck submissions to consider for use in a future article, like Brian’s Lazav, Dimir Mastermind deck or Kris’s Karona, False God deck. Only one deck submission will be chosen per article, but being selected for the next edition of Dear Azami includes not just deck advice but also a $20 coupon to the StarCityGames.com!

Email us a deck submission using this link here!

Like what you’ve seen? Feel free to explore more of “Dear Azami” here! Feel free to follow Sean on Facebook…sometimes there are extra surprises and bonus content to be found over on his Facebook Fan Page, as well as previews of the next week’s column at the end of the week! Follow Cassidy on his Facebook page here, or check out his Commander blog!

Postscript

This is the Birthing Pod decklist I played to the finals of the 20 Sided Store PTQ in Brooklyn last weekend. If you recall my noting ten-proxy Vintage was “surprisingly affordable” when you had ten wild cards you could fill in as you needed based on price and availability, this Modern deck costs $1,030.

Creatures (31)

- 4 Birds of Paradise

- 3 Kiki-Jiki, Mirror Breaker

- 1 Wall of Roots

- 2 Vendilion Clique

- 3 Kitchen Finks

- 1 Murderous Redcap

- 1 Glen Elendra Archmage

- 4 Noble Hierarch

- 3 Lotus Cobra

- 1 Linvala, Keeper of Silence

- 1 Spellskite

- 2 Deceiver Exarch

- 1 Phantasmal Image

- 2 Restoration Angel

- 1 Zealous Conscripts

- 1 Izzet Staticaster

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (23)

Spells (4)

It is not often that I feel I have my opponents completely outclassed, but with this deck it doesn’t even feel like we are playing the same game. I did not win a single die roll all day and was on the play in exactly one out of ten matches played…and it didn’t matter. Usually, losing every die roll would feel like reality’s way of telling you today is not your day so stop trying; playing this through to the finals felt like instead everything was done right and was done during the deckbuilding portion. All I had to do was hold the cards and do what the deck told me to do and it would do the heavy lifting.