Mark Rosewater is fond of saying that Magic design moves like a pendulum, constrained in its own way yet never staying still.

Similarly, Magic’s creative approach to cards has its own pendulum-like motions, its arcs and extremes.

At one high point of the creative pendulum’s motion, Magic expresses a plot through its cards. When the pendulum swings the other way, it focuses on atmosphere, prioritizing a sense of the world rather than a sequence of events set within it.

Today I’ll look at how the creative pendulum has swung between plot and atmosphere through Magic’s history, elaborating on observations I first made in a previous article, “The Gatewatch Era, So Far.”

Limited Edition Alpha: Pure Atmosphere

Before any grand narratives emerged within Magic lore, there was the first edition of the game, Limited Edition Alpha. While it oozed with flavor, a key part of Magic’s rampant early sales success, the cards themselves told no coherent story, instead giving glimpses into a fantastic world, then called “Dominia.”

From the Gray Ogre to the Drudge Skeletons, every cryptic piece of flavor text added to the atmosphere, but a plot proper was nowhere to be found.

Arabian Nights to Visions: Swinging Toward Plot

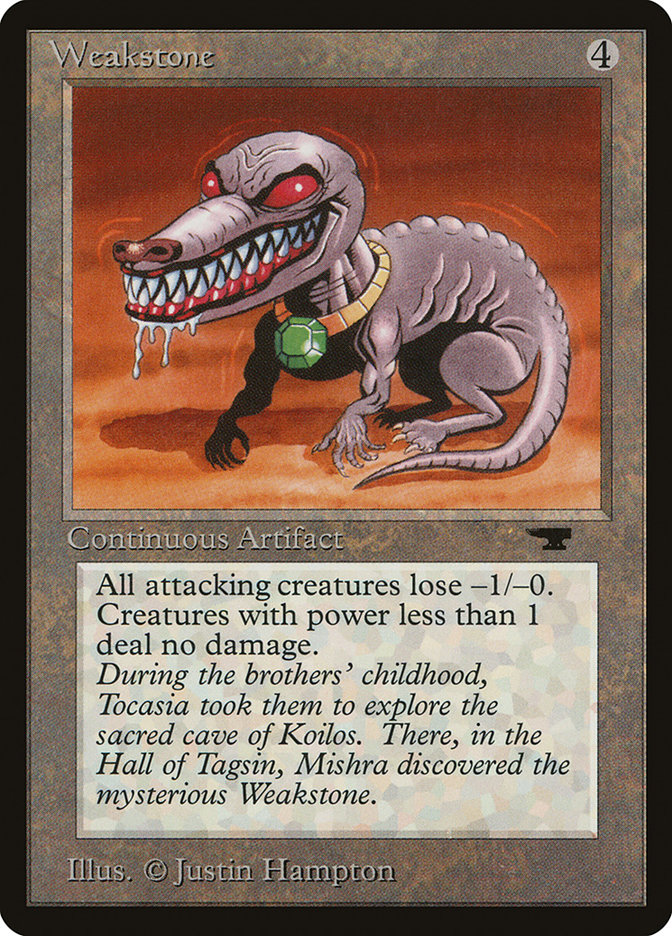

As the game grew, its lore became more elaborate. While Arabian Nights is based on the classic tale collection One Thousand and One Nights, it is still more atmospheric than making any attempt at telling a coherent story. The second expansion, Antiquities, has more elements of traditional storytelling.

Note how the flavor text on these cards has shifted toward describing events rather than merely creatures or objects. Magic was no longer content to “just” show a world; that world was put in motion.

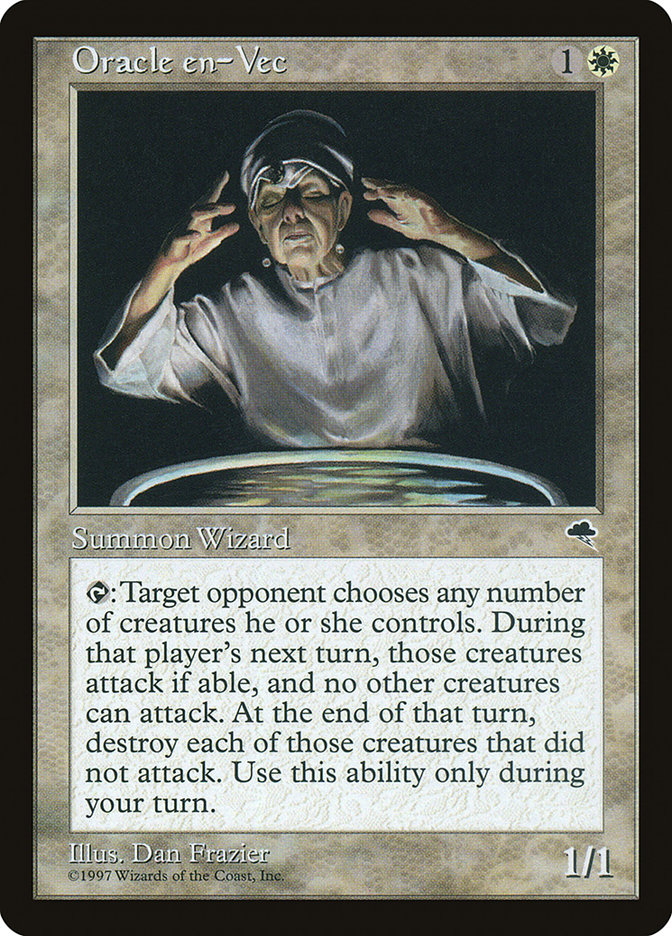

While the storytelling progress was uneven — Legends with its then-unique emphasis on legendary creatures put more emphasis on individuals rather than events — a key development soon followed when Alliances was created specifically as a sequel to Ice Age. Plot points raised in Ice Age received their payoffs in the sequel set.

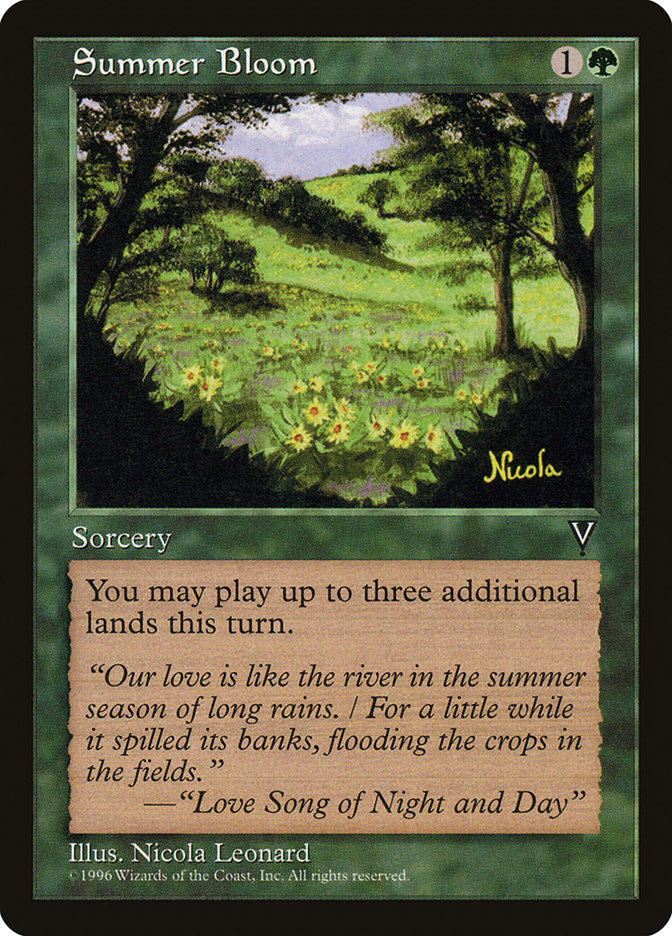

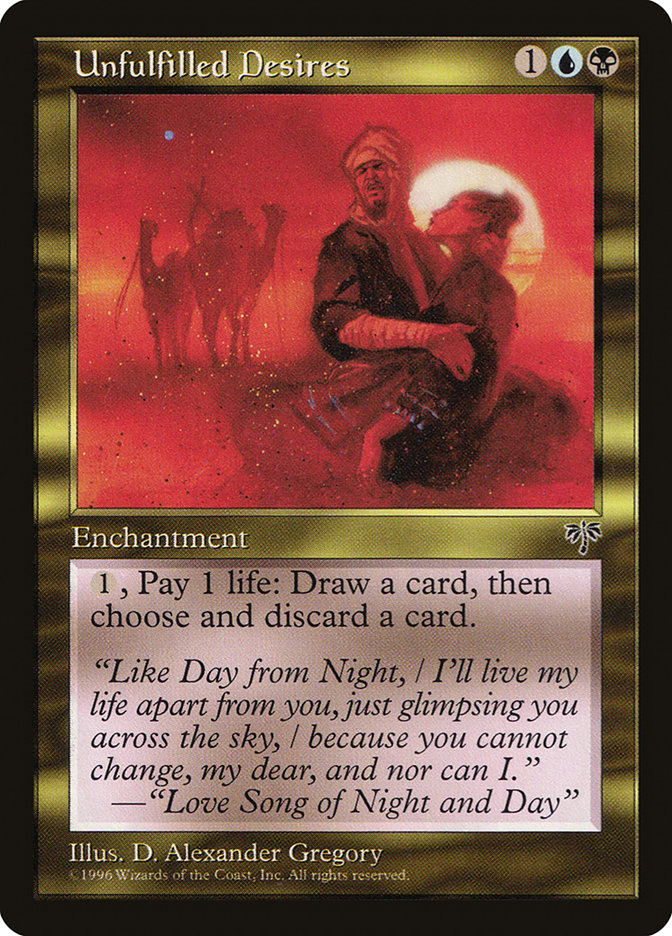

By the time Mirage block got started, the off-card lore was increasingly elaborate, and the sets Mirage and Visions themselves quoted liberally from “The Love Song of Night and Day,” a poem by Jenny Scott that lends a sense of plot to those two sets, even though the “Love Song” characters are isolated from the rest of the narrative.

But even the seventeen quotations from “The Love Song of Night and Day” were just a hint of what was to come.

Weatherlight to Apocalypse: The Weatherlight Saga, Peak Plot

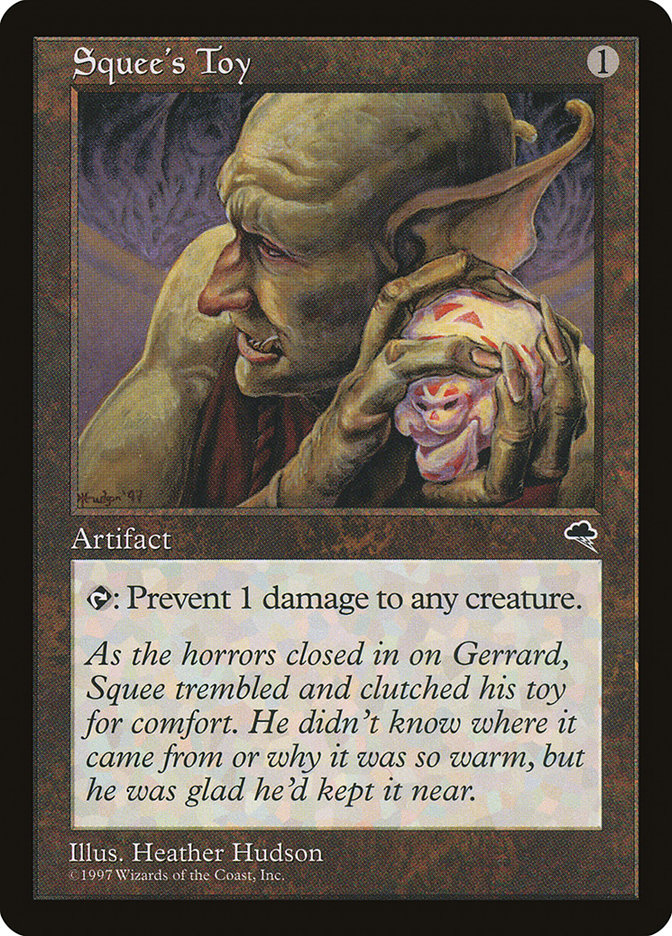

Weatherlight, named for the plane-hopping ship, set up the idea that a new cast of characters would be taking over Magic’s story, and take over they did! Gerrard, Hanna, Orim, Tahngarth, Squee…for players of a certain vintage, each name brings back a memory.

The next set, Tempest, is where things got ridiculous. As Duelist magazine pointed out, the entire storyline for Tempest was printed on the cards. That page’s image links no longer work, so here’s my version.

If that felt like a lot, you’re right. Of Tempest’s 350 cards, a full 59 of them are shown above.

For three years, hardcore flavor geeks (or those who had a subscription to the right magazine) could follow the Magic storyline with remarkable clarity, even without purchasing the books. More casual players, on the other hand, were treated to a series of increasingly cryptic and seemingly irrelevant cards as the saga went on.

Unless you happen to know that Yawgmoth promised Gerrard Capashen that he could bring back his love Hanna, Ship’s Navigator, and then Yawgmoth hid in the Hanna-simulacrum, thinking it was the one place Gerrard would never strike, how does this card make any sense?

The simple answer, as I’ve pointed out before, is that it doesn’t. Getting Magic’s story through the randomness of booster packs is an inherently nonlinear experience, and it was all too easy to miss out on vital clues and get bombarded with ultimately trivial moments instead. It’s worth noting that, while the pendulum has swung a great deal toward story in recent years, it has never again gone to this extreme.

Odyssey to Scourge: The Swing Back

Having disposed of the characters of the Weatherlight Saga in Apocalypse, Wizards of the Coast promptly started a new multiyear storyline on a remote corner of Dominaria. The plot of Odyssey and Onslaught blocks began simply enough: a Barbarian named Kamahl, like many others, wants the legendary artifact known as the Mirari. It ended with Karona, whose origin is so mind-bogglingly weird I’m just going to give you the link and let you sort it out.

While six novels’ worth of story were printed up and sold, the cards themselves showed surprisingly little of it. Oh, there were hints here and there: the Desire cycle of Odyssey, for example, shows Lieutenant Kirtar and Aboshan, Cephalid Emperor getting hold of the Mirari. But the idea of showing each plot point on a Magic card was long gone.

And an even bolder move away from storytelling on cards was in the works.

Mirrodin to Future Sight: New Worlds and Old, Peak Atmosphere

Scourge was the last Expert-level Magic expansion released before Magic’s tenth anniversary in 2003, and Mirrodin was the first set to come out after it. Mirrodin marked a staggering change in the game’s creative approach, offering a previously unseen world with no recurring characters (on the cards, at any rate; Karn was involved at the very end of the novels).

It would be nonsense to say nothing happened during Mirrodin block (the eruption of a fifth sun from a plane’s core is a pretty big deal!), but the background information is low-key and the creative emphasis is on showcasing the world rather than following someone’s adventures within it.

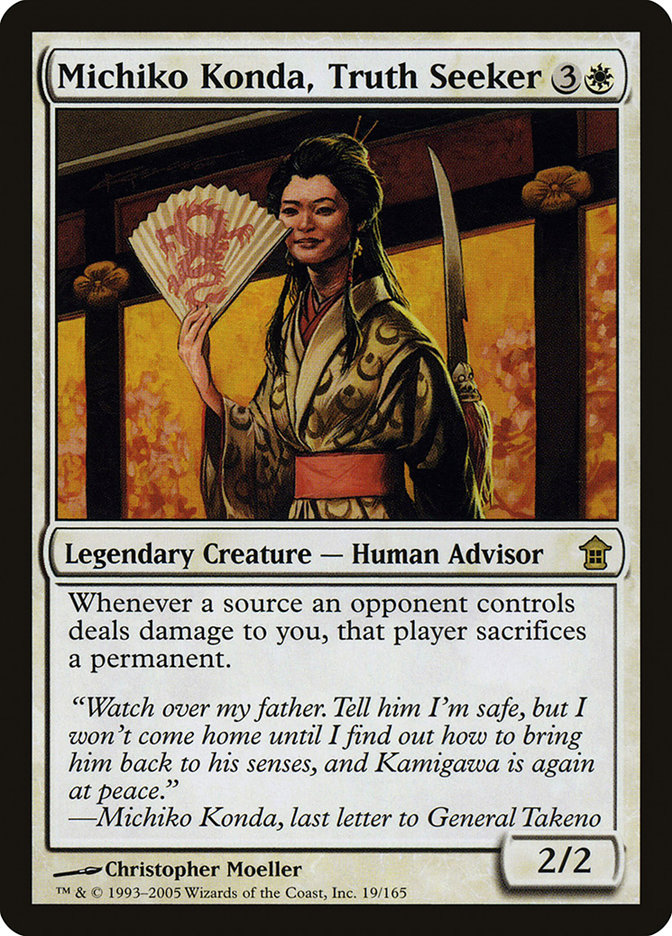

Much the same pattern holds for Kamigawa block, though the oft-referenced Kami War gets more attention in cards’ flavor text than Glissa Sunseeker’s quest did during Mirrodin.

And then there’s Ravnica block, which is almost as purely atmospheric as Alpha long ago. Its block structure split the ten guilds up into groups of four, three, and three, focusing intently on group members in each set. By its very structure, Ravnica block eschewed a plot, spending its entire time filling out its world.

Ravnica’s follow-up, Time Spiral block, took an outlandish course. Possessing almost an anti-plot, it mined Magic’s past (Time Spiral), an alternate present (Planar Chaos), and a series of potential futures (Future Sight) for material. Again, the novels had a story — a crucial one, in fact, that forever changed how planeswalkers appeared in the game — but the narrative coherence of the cards themselves was minimal.

Lorwyn to Dragons of Tarkir: Planeswalker Stories, The Pendulum Swings

Coinciding with “The Mending” that depowered planeswalkers to the point where they could be included in regular games of Magic, the game began incorporating more story into its cards.

For Lorwyn / Shadowmoor block, this largely took the form of comparison and contrast, as the two opposites of the plane revealed themselves in sequence.

With Alara block, the newly depowered planeswalkers took center stage for the first time. The card Conflux, printed within the set Conflux, is a true “story card” the likes of which hadn’t been seen in years.

Zendikar block, though seemingly atmospheric, turned plot-heavy with the Rise of the Eldrazi. Similarly, Scars of Mirrodin, returning to a setting for the first time in several block-years, is unavoidably plot-rich with its slide into New Phyrexia. The Innistrad block also showed a willingness to change the plane, this time for the better (from humanity’s perspective, at least).

Return to Ravnica provides an excellent storytelling contrast with the original Ravnica; its first two sets speak of unrest, and Dragon’s Maze provides its resolution. Theros block chronicles the rise and fall of Xenagos, a planeswalker who briefly joined the plane’s pantheon.

Khans of Tarkir block, like Time Spiral before it, plays with time as a crucial element of its plot. The middle set of the block, Fate Reforged, takes place more than a millennium before either Khans or Dragons, with the two flanking sets showing the before-and-after of Sarkhan’s meddling.

Battle for Zendikar to Hour of Devastation: The Gatewatch, Peak Story

And at last we get to the current period of Magic storytelling, focused on the Gatewatch. Battle for Zendikar block focused on its formation and first victory against Ulamog and Kozilek, saving the former Eldrazi prison-plane. Shadows over Innistrad block revolved around Jace Beleren investigating the mysteries of the increasingly twisted plane and added Liliana to the Gatewatch.

Kaladesh block saw Chandra Nalaar confront her past and, after a little bit of political instability, the addition of Ajani Goldmane to the Gatewatch; Kaladesh also saw the introduction of called-out “Story Spotlight” cards to guide players through important plot points.

Then there’s Amonkhet block, the most recent as I write this. In remarkably compressed time, the Gatewatch (minus Ajani, who’s gone to seek allies on Dominaria) lands on the Ancient Egyptian-themed plane of Amonkhet, finds some seriously creepy mysteries, and witnesses the plane’s equivalent of the Second Coming. But there’s no heaven waiting for Amonkhet’s natives or the Gatewatch; Nicol Bolas, God-Pharaoh has made sure of that.

Mark Rosewater has promised that the planeswalkers of the Gatewatch will have a lessened role within the on-card Magic story after Hour of Devastation. What that means for plot expression on cards has yet to be seen, but the announced future breakup of the block model strongly suggests that Magic set releases will be tied more closely than ever to story needs.

Will the pendulum swing back toward less plot-oriented cardstock? Will we remain at or near peak plot? The Vorthos in me is excited to find out!