Trent Reznor is a master of addition by subtraction.

The Nine Inch Nails track Happiness in Slavery contains a great example of addition by subtraction a little over three minutes into the song. If we start 2:57 into the song, we’ll hear about fourteen seconds of music before he cuts most of the music out during the final line of the second verse of the song. After a verse of increasing intensity, increasing density of sounds, increasing abrasiveness, the sudden absence of all of the sounds we had grown accustomed to hearing adds an incredible emphasis on what remains: the sound of his voice and the words he’s saying.

By subtracting that which is not the emotional experience he’s expressing, he shines a powerful spotlight on what is the emotional experience he’s expressing.

Not every removal of sound in music need be as dramatic as a full cut out at the end of an emotional verse. If one is making a song and it sounds like the drums aren’t hitting hard enough anymore, it might seem tempting to find drums that hit even harder or to turn their volume up. However, more commonly, the better approach is to cut the drums out entirely.

Once someone’s ears get tired of hearing a particular sound, they can start to become numb to it, to filter it out. If the drum was hitting hard earlier in the song, the experience of feeling like it’s not hitting hard anymore is usually a good sign that it’s been in for too long. If you cut the drum out entirely for sixteen bars, after someone’s ears are tired of it, they get a chance to rest and might be ready for it again. If you cut the drum out before they’re tired of it, they might get a chance to actually miss it.

In general, the louder music is, the more powerful of an emotional experience it’s trying to evoke. The musician making a song usually doesn’t get to pick how loud the listener chooses to listen to it. Besides, every listener’s appetite for volume is different. It’s better to think about how loud the sounds are relative to the other sounds in a given song.

In Magic, cards generally do good things for us. However, adding more cards to our deck dilutes the rest of the deck. One of the most efficient ways to gain an advantage in Magic is to subtract cards from your deck until you are playing the minimum. While there are times and places where some other goal may outweigh the advantage gained by cutting a deck down to 40, or 60, or 100, in general, cutting the worst card in your deck makes you draw every other card in the deck more frequently, every one of which is better by definition (assuming you were right in what you cut).

There’s a ton to say on playing less than 61 cards, but suffice it to say, subtracting that last card is one of the oldest and most reliable ways to add to the rest of your deck.

However, that’s not the only way to employ addition by subtraction in Magic.

Cutting a Theme

Synergies are fun.

Taking two things and making them more than the some of the parts is a very rewarding part of Magic and deckbuilding. What’s even more fun is overlapping synergies, “spider webs” of interactions.

The experience is at a completely different level when you’re balancing the value of a creature being a specific type, the value of stat-granting cards with multiplier skills like lifelink or double strike, the value of +1/+1 counters specifically, the ability to pump your opponent’s creatures when you have kill spells that key off of power, the ability to discard cards with graveyard interactions, the ability to put extra cards into your hand that can be discarded for value, the ability to kill your own creature that does a damage to you every turn, the ability to sacrifice extra artifacts for benefit, and so on, and so on.

While there is room for a great deal of synergy for many interactions in a deck, there is a real pressure from certain strategies that encourage you to go as far as you can in a certain direction. For instance, a deck that utilizes Goblins and artifacts. Every non-Goblin you subtract adds to your Goblin count. Every non-artifact you subtract, adds to your artifact count.

Even in decks that rely on relatively tight packages, such as Sneak Attack + Griselbrand and Emrakul, there countless tangential themes you might employ. For instance:

Sometimes, each individual theme might seem good, but there’s even more value to be gained by subtracting a theme that doesn’t add as much as some of the other themes. After all, cutting Through the Breach leaves more room for Preordains or Spell Pierces or whatever other cards might help us more reliably set up our primary themes…or protect them.

Using Bad Cards in Broken Combos

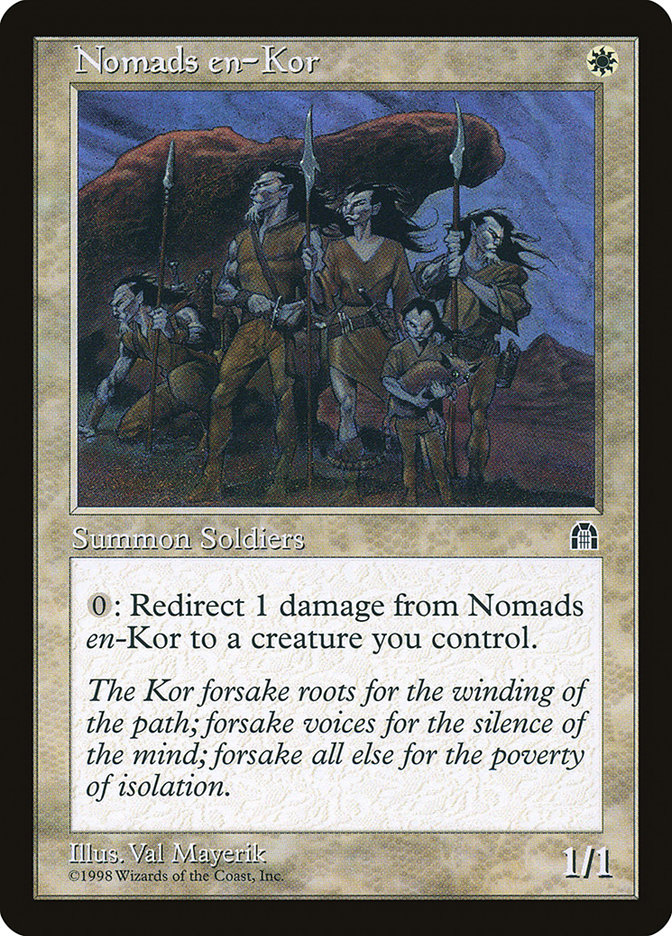

Let’s say you’ve got some combo that mills your entire library, like Nomad En-Kor + Cephalid Illusionist, Mesmeric Orb + Basalt Monolith, or Balustrade Spy with no lands in your deck.

From here, perhaps you’re able to play enough Narcomoebas to Flashback Dread Return. But, what to target?

One possibility is to Dread Return a Reveillark. Then sacrifice the Reveillark to Cabal Therapy, returning Carrion Feeder and Body Double (copying Reveillark). Even if we’ve drawn one of the combo pieces, we can target ourselves with a Cabal Therapy, particularly if we have four Narcomoebas, rather than just three.

Then sacrifice the Body Double to return Body Double and Mogg Fanatic. Now, you can sacrifice the Mogg Fanatic as many times as you want, since every time your Body Double dies, it gets itself back plus one more creature.

While Carrion Feeder isn’t a great card to draw, in general, the inclusion of it and all of the above mentioned “bad cards” (bad to draw, not in general) make any of the above two-card combos that mill yourself into a potentially game-winning play. This is a very powerful strategy with breathtaking speed. However, that’s also a lot of potential bad draws.

Cabal Therapy doesn’t really count since it has so much utility when drawn. You can just play it like a normal Magic card and have it do great work. Nomad En-Kor and Cephalid Illusionist may seem like “bad cards;” but they are some of your best cards in a deck like this, since they are each half of “win the game.” In some ways, it’s like they are each ten-damage burn spells, but you don’t get the damage until you’ve played both.

Nevertheless, that’s nine bad cards. Sure, you can discard a Narcomoeba to Force of Will or put it back with Brainstorm, and that’s not nothing; but still, with over 1/7th of your deck bad cards, it’s like you’re starting every game with a mulligan. Then, more than 1/7th of your draws are particularly bad.

One of the most profound ways to improve such a deck is to figure out how to play less bad cards. While there is always the question of whether you can get greedy and cut a Narcomoeba, or if a Bridge from Below is worth more than the fourth Narcomoeba, there’s also the issue of the specific kill. In this case, there are four one-ofs that are being combined to make Dread Return + Narcomoebas a kill. What if we could do it with three?

In searching for more efficient kills, we might develop a line of play where we Dread Return Karmic Guide instead of Reveillark. From there, we use its ability to return Kiki-Jiki, Mirror Breaker. Finally, we copy the Karmic Guide with Kiki-Jiki to return Deceiver Exarch, untapping Kiki-Jiki and starting the loop.

By turn 3, we’ve naturally seen nine and a half cards on the average (the half a card is because of being on the play half the time and the draw the other half of the time). With nine dead cards in our deck, we going to draw an average of 1.42 bad cards by then. Cutting our total number of bad cards from nine to eight reduces our average number drawn by turn 3 down to 1.26 cards.

That’s a difference of 0.16 cards. Who cares?

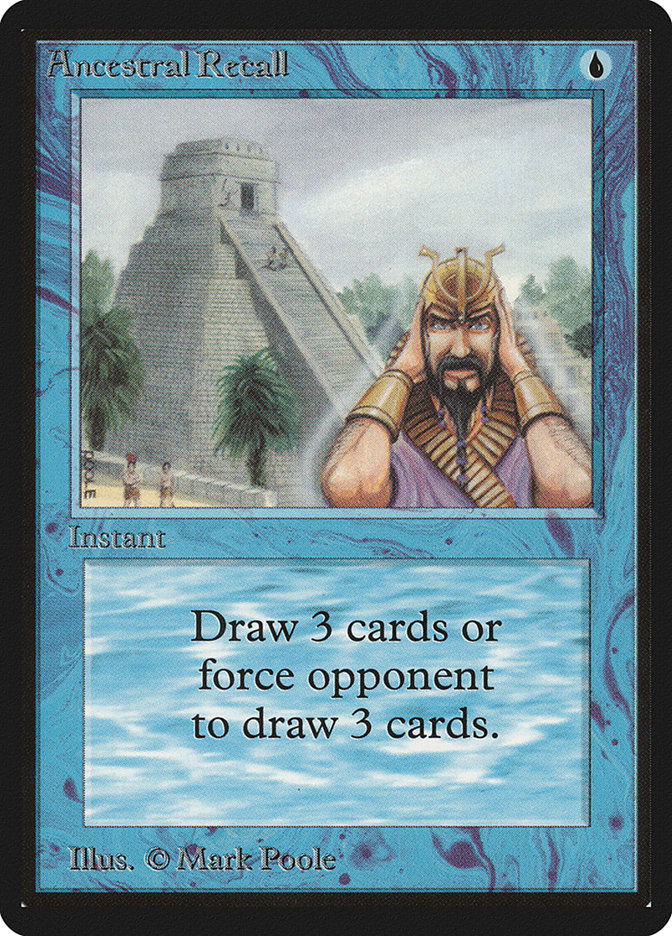

Ancestral Recall is one of the absolute most broken Magic cards of all time and is extremely banned in Legacy. If you were able to add Ancestral Recall to your deck, you’d draw at an extra 0.32 cards per game by turn 3 (at least since it would also improve mulligan decisions and makes your Ponders better, etc). If you can replace even a single bad card with something good, you just improved your deck approximately half an Ancestral Recall’s worth.

Put a different way, it’s like you get a free mulligan once every six games.

That’s seriously so good.

That’s addition by subtraction.

Preparation

Want to get better at Magic? Effective preparation for an event is one of the best possible ways to get better and increase your chances in the event. Unfortunately, we don’t have all the time in the world to spend preparing for Magic tournaments. In fact, it can feel like we just don’t have the time to prepare for most tournaments the way we’d like. Besides, additional preparation isn’t always “possible” for external reasons, like availability of opponents.

However, sometimes, even when addition seems impossible, there’s subtraction.

Let’s say you’re only going to be able to play games one evening a week for the two weeks leading up to the event you’re preparing for. Is there anything in the way of the most efficient testing that you can subtract?

● Building decks takes time. Can you subtract that time expenditure from your preparation time, leaving more time to play games?

● Making plans takes time. If everyone involved is on the same page about the plan, the process beforehand, that leaves more time to play games. There’s nothing worse than wasting all of your game time arguing over whether games should be Constructed or Draft, or how cards will be divided up in a draft, or whether sideboarding should be involved.

● Distractions take time. As a human, you’ve got stuff to get done. Feeding pets, washing dishes, clearing off a table, finding enough chairs, talking to a cousin on the phone, finishing watching a show; there are countless possible everyday obstacles that each take time. Every minute you subtract of these from your game-playing time by getting them done ahead of time, adds a minute of potential to play games.

● Arguing about which deck is advantaged in a matchup takes time. This one can seem non-intuitive to want to subtract…

After all, isn’t one of the major points of playing these preparation games? To gain a greater understanding of which decks are advantaged in various matchups? Sure (depending on what you’re trying to accomplish), and some of that can be good.

Yet those discussions can also take place in small bite-sized chunks online, on a phone, on a walk somewhere, on a bus, etc. They can also be informed by everything else you learn the rest of that day. It can be very tempting to want to explain everything away after winning the first three games of a set, and sometimes both players are already on the same page that fast. However, telling someone their new brew sucks after it loses its first three games against the best deck isn’t necessarily constructive.

Sometimes, it’ll be important to figure things out early in the gaming session to help inform later focus. However, in the heat of the moment, people also aren’t being their most rational, particularly if one or more people have some amount of ego invested in or against an idea. Besides, there’s a very real risk of selection bias.

Let’s say that you believe a particular matchup is good for you and someone else disagrees with you. If you play four games and lose 1-3, there’s no reason that should be considered conclusive (at least not because of the record. The texture of the games may tell another story). What about all of your other experience? Are you really going to throw it all out because of a 1-3 result one time?

Likewise, if you beat someone’s brew with W/U Flash 3-1 when they claimed that was a good matchup, we should be hesitant about putting too much stock in those results. If we hold a double standard, that’s a bias. It’s like “keeping track” of results after each time you finish ahead in a set and “not counting” sets where you were experimenting with two less this, two extra that.

If you select for sets where you already finished ahead, of course the results will be biased!

…

Want to improve your testing?

Want to add win percentage to your game?

Want to have a better time at tournaments or whenever gaming?

Make a list of the least efficient ways you spend your time, the ways you spend time that you’re least happy with in retrospect, the time expenditures that least represent the best version of your highest vision of yourself…

…Then subtract one of those.