If I’m going to be snarky, there were no Revelations at Pro Tour Battle for Zendikar. After all, this wasn’t legal:

On the other hand, these both were:

For what it’s worth, I did hear rumors that a Nissa’s Revelation or two was in one of the Eldrazi Ramp decks, but they were never confirmed. Regardless,

what I’m actually talking about are some of the revelations I had leading into the preparation for the Pro Tour. Each of these were things that had an

impact, small or large, on my event, but also, just in general, on my understanding of Magic beyond the event.

Here are a few of my revelations from PTBFZ.

Revelations from Ian DeGraff

My good friend Ian is the kind of fun and friendly person that you’re always glad you see. Aside from that, though, he’s got a keen Magic mind. While he

wasn’t as influential on Owen Turtenwald as their mutual friend Tommy Kolowith, Ian was an early mentor for Owen, leading into his breakout GP Columbus

performance almost ten years ago. Ian is the kind of guy that will be so set on helping people out that he’ll accidentally register 64 cards (like he did

at that same GP Columbus) because he was distracted by the desire to help answer everyone’s last minute deck change thoughts.

I definitely credit Ian with helping to build my understanding of Legacy back when I was first commentating for SCGLive. He’s been an occasional

collaborator as well, helping me polish up my

classic, Eminent Domain, over ten years ago.

Beyond everything else, though, Ian is fun. He tells a great story and can make people laugh.

So, when I conscripted Ian to be my second head at the Two-Headed Giant event for the Battle for Zendikar Prerelease, I was glad when he came to

join me, even though he’d played at the midnight Prerelease and was basically on no sleep.

It was just a Prerelease, but we had fun crushing the event, and despite his earlier protests, he grudgingly agreed that the aggressive build I’d suggested

was better than the more powerful, slower build that he’d advocated, despite the fact that I hadn’t included his new favorite Limited card, Vampiric Rites.

Later, we were discussing another Standard-legal card, one not even in Battle for Zendikar, and one that had been around

for a little bit already. “What do you think the flipped Jace says, Adrian?” he asked. “What does its minus ability say?”

“Minus three: give a card Flashback,” I said.

“No,” he said. “It almost does, but it doesn’t.”

Reading it out loud, I said, “‘Minus three: You may cast target instant or sorcery card from your graveyard this turn. If that card would be put into your

graveyard this turn, exile it instead.’ Huh.”

Jace, Telepath Unbound is not Snapcaster Mage, even if we sometimes shortcut it to think that he is. Jace’s -3 is not Flashback. There

aren’t many Standard applications for this. But in formats with other alternative mana costs (cards like Force of Will and Needlebite Trap)…

More importantly, though, is the reminder that the words on cards have consequences. This should be apparent during a Prerelease weekend, when reading

cards is at a premium, but it isn’t always obvious.

Assuming we know what a card does is a great way to lose to what a card really does (or not pick up a win you could have).

Thanks, Ian.

Revelations from Sam Black

Early on in Madison’s Limited testing, things started coming together. We could see the general outline of a number of decks, from B/W Vampires, to the

various devoid decks in the world of Grixis, to G/U Converge, and more.

One of the things that wasn’t happening, though, was that we weren’t really seeing any breakout bizarro archetype. Oftentimes, if you really get to know a

format, there is a strange archetype hiding in the middle of it. Long ago, for example, OLS Draft had the hidden Pemmin’s Aura combo deck that was actually

fairly easy to get and used cards you’d want in you multicolor deck anyway.

More recently, the Innistrad Draft deck that people love to remember was the so-called “Spiders” or Spider Spawning deck, employing self-milling

strategies to make the card become absurd. While I know a ton of people found the Spider Spawning deck, Sam was the first person I saw do it.

At one draft, perhaps our ninth or tenth, Sam dropped down a card that Ian had mentioned to me before:

Looking at the card, reading the card, I could imagine it being powerful. Pretty quickly, though, all hell broke loose.

At first it was just Eyeless Watcher. Then it was a Call the Scions. Then it was another token producer and another. All the while he was building up a

fortress with other cards.

It honestly felt like he was G/W Megamorph with an Evolutionary Leap on the battlefield and I was the idiot yokel who was trying to use spot removal on his

creatures.

Sam ended up drafting it repeatedly. While I never ended up playing it at the Pro Tour or at the Grand Prix, I knew that the deck existed, this little

monstrosity that could come in the form of a thirteenth pick card in the second pack, and just make a G/B Tokens deck so resilient it is

frightening.

I was at a point in the format where I felt like I’d seen the broad strokes of what was possible in drafting Battle for Zendikar. I hadn’t seen

anything to suggest that there were any micro-archetypes to pursue.

Thanks, Sam, for reminding me that there usually are.

Revelations from Alan Comer

One of the most amazing moments in prep for the Pro Tour came to me from Alan Comer.

Alan is in the first class of the Magic Hall of Fame, and sometimes, people have been known to besmirch his relevance. I didn’t have the privilege of

voting for him on that first ballot, I started being able to vote for the next ballot, but when I look at the Hall of Fame stats, he’s someone

who has exemplary Top 8 performances (five PT Top 8s) and good Top 32 and Top 64 numbers. More importantly, though, he has the kind of integrity that makes

me glad he’s in the Hall.

At an important Pro Tour match way back in 1999, he’d accidentally played game 1 with a deck less than 60; from the previous match, he’d forgotten to put

in the cards he’d sided out, but he did take out the cards he’d sideboarded in. His deck, empty of some important pieces, didn’t function right, and I won

the bad matchup in game 1. After he realized his error, he alerted a judge immediately, even though he knew that, at the time, the penalty would likely be

a game loss. No one would have had to have known, and he’d already gotten a severe disadvantage in the first game because of it, but he wouldn’t have it

any other way.

I realized then that as good as I thought I was on the integrity front, I had a new goal to aspire to.

This last Pro Tour marks the first time I’ve had the privilege of working with Alan. He is a father and has a lot going on in his day-to-day, so he doesn’t

approach the game with the same tenacity he did in his early years, but he is still one of the people whose mind for the game can be incredibly surprising.

At times, he reminds you, “Oh, yeah, there is a reason he was such a huge influence on Magic.”

In a playtest session, he was playing R/G Landfall, and I realized he was just playing the deck differently than anyone I’d seen play the deck. Most of my

testing with the deck had been online, and most of my testing against the deck had been in person with my Madison teammates Aaron Lewis and Stephen Neal. I

liked the deck a lot, and while I was still considering perhaps shifting back to playing it, I had my reservations. The land was one of them.

I’ve seen many writers talk about how Landfall builds of Atarka’s Command decks need more land than non-Landfall builds. Ari Lax’s team, for example, ran

24 land. We ran considerably less at 22. The typical Atarka Red deck was running 21 to 20.

Alan was on a build of the list about two cards off our teammate, Zvi’s, version. In one match, he surprised me by missing a land drop, and then dropping

two fetches in a row over the next turns. It contributed to him just barely killing me.

“Lucky pull, there,” I said.

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“Those lands, after missing your land drop.”

“No,” he laughed. “I was holding them for when they’d have a better use.”

Alan was looking at his lands as though they were burn spells. Getting two out of a Wooded Foothills wasn’t sufficient for what his hand looked like. He

waited a full turn so that he’d have two landfall creatures. It cost him two damage on the one turn, but paid off as four damage on the following

turn.

In other games, not feeling like he could risk (or need to risk) the loss of damage, he didn’t hold back the land.

In talking to him about it, he said, “You know, everyone says we might need even more land. I think they’re just wrong!”

Watching him play, I think he was right. We were all, all of us, just playing the deck less well than he was.

I didn’t switch back to R/G Landfall. But because of Alan I suddenly felt like I needed to reevaluate whether or not I should be playing the deck. Hell, I

felt like I had to reevaluate everything I thought I knew about the deck.

That night, I called and I shared the incident with my friend and constant collaborator, Ronny Serio. There was a pause on the phone.

“Revelatory,” he finally said.

I couldn’t agree more.

I know it intellectually, but it had been a while since I’d been reminded that even the most straightforward of decks have play to them, and just how

critical even the small things, like laying a land, can be. Perhaps that is unsurprising coming from the man that brought us Miracle Grow, Turbo-Xerox, and

the roots of the modern Legacy manabase. What Alan showed me was both so simple, and yet so far reaching, I suddenly had to completely revisit my

understanding of Magical reality.

Thank you, Alan. It wasn’t the first time you did that to me.

Revelations from Darwin Kastle and Rob Dougherty

I ran into Darwin a few days before the event, and I ran into Rob right on Day One of the event. One of the things that came to me from them wasn’t

specifically about Magic, but it deeply related to Magic.

If you don’t know, Darwin and Rob are responsible for Star Realms, which is, in my

not so humble opinion, the best deckbuilding game on the market. Now, I’m a bit biased, but it is what it is.

I’m constantly playing this game. Recently, a new set came out, and I ended up losing a game. Moments later, I realized I should have won.

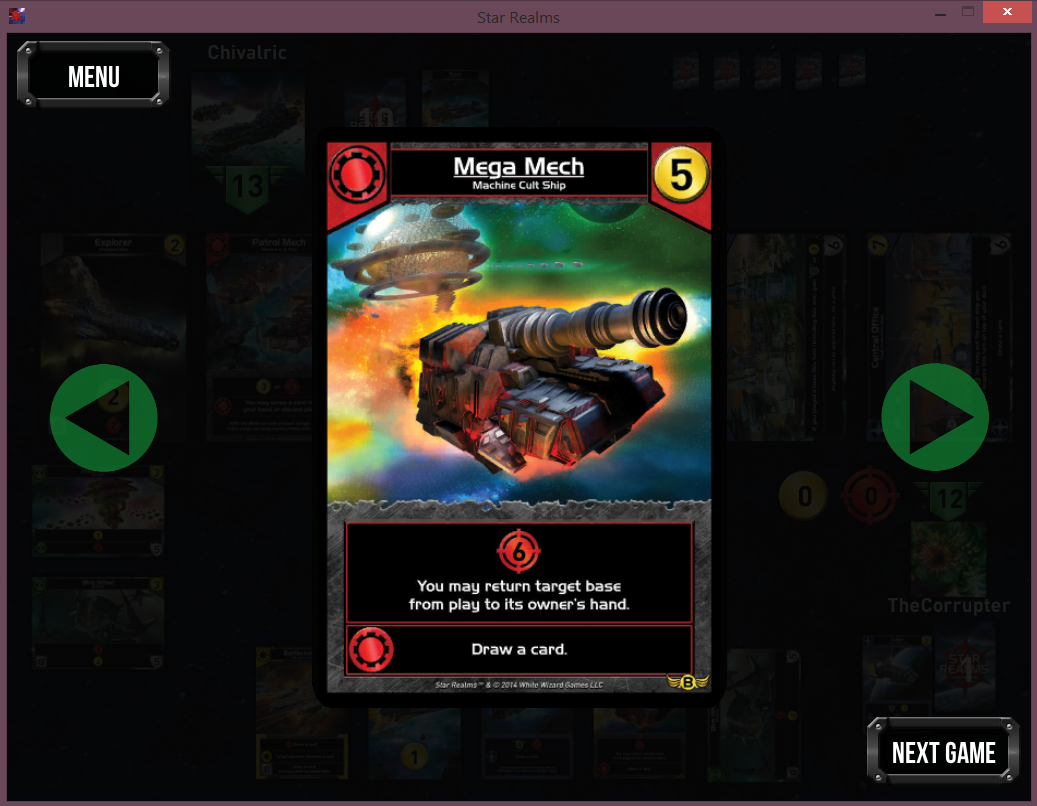

If you don’t play, don’t worry about the rules. Earlier in the game, I’d had a chance to kill my opponent with the new card Mega Mech. However, instead of

doing that, I made a different set of plays.

You see, “return target base” usually works best when you use it on your own bases. I missed the chance, in this instance, to return an opponent’s base to

their hand, and in so doing, could have killed them. This, in turn, got me thinking of other, less obvious good ways to use the card. For example, return

one base of an opponent so you can blow up another.

I was thinking about that throughout the weekend. In one match, a match that I lost, I remembered it again. My opponent was playing Hangarback Walker, and

because of Despise, I knew that they had a Valorous Stance in hand. At one point, I let them get their Hangarback up to 4/4, and later, attempted to use

Utter End to remove it. In response, they cast Valorous Stance, and while I won the ensuing counter-war, I never needed to have gotten into one. I had

neglected to think of the other ways in which Valorous Stance could be used, and I allowed my opponent to maneuver me into a situation which ended up

losing me that game.

After that match, I thought of Darwin and Rob, both of whom have full lives outside of Magic doing game design, both of whom are Hall of Famers. At the

peak of their game, I’m sure that they not only would have seen the play coming and avoided it, but if they were on the other side of the table, they would

probably have been able to work the game so that they’d have more ability to leverage an atypical use of the card.

The mistake I made in Star Realms and the mistake I made in that match versus Jeskai Ascendancy both have the same root: presumption. I presumed because I

didn’t have anything that would be susceptible to making their card indestructible, and since I didn’t have any large creatures, I needn’t imagine

Valorous Stance as anything other than a blank card. Instead, it precipitated a counterspell war that I may have won, but the costs of that battle lost me

the war.

After the match I thought about the mistakes in the two very different games, and I thought about Darwin and Rob. Tunnel vision is one of my real

weaknesses in play, and the rest of the tournament on Day Two I tried to channel the kinds of ways of thinking that let’s you be open to all of the

possible uses of a card. I started playing my Constructed matches with that open eye to possibility that for most people exists most in Limited in Magic,

if it exists at all.

I didn’t lose another match after that. Perhaps it was because I had good matchups. But I also think it was, in part, because I had my head in a space that

was closer to the right place for it to be in the first place, a place that I know I’m guilty of not being in nearly as often as I should be.

But I’m going to try to be there more.

Thanks, Darwin. Thanks, Rob.

Closing

Just in general, there is always a lot that you can do to improve your game. We should always be looking to learn, and that goes for more than just in the

world of Magic.

If you’re looking to grow, you have to be open to finding knowledge, to finding lessons. I’m a stubborn person, but I’m also, for better or for worse, one

of those people who is deeply interested in the truth at the heart of the matter. This was probably why I spent time in a PhD program and why I spent so

much time in Magic thinking about the theory of the game and trying to build decks that took advantage of strange possibilities that opened up with

interesting combinations of cards.

Turning your eye for growth towards yourself can be a difficult process, but it is an endeavor worth doing.

As you read this, I’m probably already in Indianapolis getting ready for Grand Prix

Indy! If you’re nearby, come by and check out the costume contest at 6 PM, or just get registered for the main event and do battle Saturday and

Sunday.

I hope I see you there!