Every once and a while a meme cruises across the internet and brings with it not just a bit of joy but a good reminder of the past. The best of these can come with lessons that you can use to apply to the future.

On my Facebook page, I asked Magic players what card they thought of when they thought of me and got a flurry of responses. I did the same on my Twitter, and among the many responses, I got this one from Craig Wescoe:

@AdrianLSullivan 1. Sylvan Library 2. Gaea's Blessing 3. Orcish Librarian 4. Jaya Ballard, Task Mage 5. Glacial Wall (chevy blue)

— Craig Wescoe (@Brimaz4Life) November 18, 2016

Needless to say, I loved this response, as it brought up so many memories of things I’d learned over my time playing Magic. It occurred to me that there were some ways in which I could do something I love: use the past as a means to discuss Magic overall.

So, let’s go back. Way back.

A million years ago, way back in 1998, my Cabal Rogue collaborator and future Dojo boss, Rob Hahn, would send an email to our think tank. Wouldn’t it be great, he said, to build a deck with the new card Oath of Druids and counterspells?! Just think about the card with Verdant Force!

I immediately thought that he was off on the Verdant Force, but basically right on with the idea of Counterspells and Oath of Druids. I made a deck and tuned it with the help of Cabal Rogue, ending with

Here is that Oath deck, the very first Counter-Oath deck of note, designed by me with help from Cabal Rogue and piloted by Jim Hustad.

Creatures (7)

Lands (22)

Spells (31)

- 3 Brainstorm

- 4 Counterspell

- 4 Oath of Druids

- 3 Propaganda

- 2 Sylvan Library

- 2 Gaea's Blessing

- 3 Mana Leak

- 4 Impulse

- 2 Forbid

- 2 Force Spike

- 2 Creeping Mold

Sideboard

The deck was both flawed and great.

It was great because it was basically just more powerful than anything else in Standard, and I was gratified in the months following this event to see people win numerous events with the deck. Though, they did have to make some fixes. It was also rough.

@AdrianLSullivan Spike Hatcher

— Tim Aten (@AllFairness) November 18, 2016

Tim Aten called this out, rightly.

See that big mess of a card? This card was a huge lesson for me.

Sometimes you can have a great deck, but the greatness of the deck hides the deck’s flaws. In the case of this deck, it should have been obvious that Spike Hatcher was just, well, bad. In my head, I had decided for some reason that the deck needed to have three big creatures. I had gone with the Spike Hatcher because it could be used to pump up a Spike Feeder for a lot of life. My friend (but not yet collaborator) Ronny Serio promptly took out the Hatcher for the obvious replacement, Spike Weaver, and hopped into a Nationals Grinder with his best approximation of the deck.

At first, I defended the Spike Hatcher to people. In fact, I defended it to numerous people in playtesting. “We need enough finishers!” I’d say. What I wasn’t paying attention to was the fact that the card wasn’t really accomplishing anything other than being big. This seemed good, but it wasn’t that the card was good; it was that Oath of Druids was so absurd that it needed very little help.

Over time, I came to realize this was a mistake. It did, however, take more time than it should have. To me, the lesson of Spike Hatcher is twofold:

A deck can be good enough fundamentally that the mistakes in the deck can hide; winning doesn’t necessarily mean that we have understanding.

It took me a while, Aten, but I think I get it now.

Also in this deck are two Gaea’s Blessings, the card that more people associated with me than any other card. It is still one of my favorite cards of all time, and fundamentally a part of why the Counter-Oath deck works.

Gaea’s Blessing feels innocuous. Used in its primary way, it only barely changes the nature of what is going to happen in the game. Used off its trigger, it provides something free, but again, generally an effect that would be thought of as minor.

Still, fundamentally, library manipulation and increasing threat density can add up like compound interest. Library manipulation can help establish advantage a game of inevitability, and in that game of inevitability, library manipulation can stitch the game closed. The lesson of Gaea’s Blessing is one that I would carry through my Magic career into the modern era, and it is still true:

In games of inevitability, seek card choices that can make long games unwinnable for an opponent.

This is actually a part of the reason another card from another deck was mentioned by several people:

While I did famously lose my semifinal match at Pro Tour Dragons of Tarkir after casting this card, it was wildly unlikely. As Zvi Mowshowitz put it, “The odds of you losing after casting that card in that position were incredibly low!” Me being me, I checked into it after the match: I was at less than 2% to whiff.

While the card did fail me in that moment, it also carried me to that moment, and it was a fundamental part of how I closed out an endless amount of games. A stable game could be created, and then an Interpret the Signs would do much more than Dig through Time: it would simply end it.

Here’s that U/B Control deck from PT Dragons of Tarkir:

Planeswalkers (5)

Lands (27)

Spells (28)

This deck was an absolute labor of love, and it would be a deck I would pilot again and again in tournament after tournament, in many, many different configurations.

This was a commonly named card for people in thinking of me, for many reasons. My favorite was from my friend Jennifer Peers, who mentioned it because we ended up having to crack packs to replace a creature I’d stolen from her with the card in playtesting, only to find the Akroan Crusader or what-have-you later that day.

What Ashiok, Nightmare Weaver makes me think of, though, is simple:

Card values are fluid and can radically change with a changed context.

I actively hated this card for a long time. In the era of Sphinx’s Revelation, many Esper or U/B Control lists would run Ashiok, and I basically always thought of it as an utter waste of time. While I saw some people have a degree of success with the card, I was reminded of the Spike Hatcher lesson, where winning is distracting you from the cards that are holding you back. In testing session after testing session, Ashiok kept coming up short, even in the matchups it was supposed to be the greatest in.

After Sphinx’s Revelation went away, though, the world changed. Things became fundamentally slower, and suddenly Ashiok, Nightmare Weaver wasn’t just an anemic little speed bump but a powerful disruption and card advantage spell. Again and again, it would draw fire from an opponent but still keep me moving towards an inevitable game, and yet it couldn’t be ignored, lest it take over.

Even the cards you hate can become worthwhile given the right circumstances.

This is similar to the opposite kind of move.

In the case of this card, from the moment I saw it, I was in love. I even had it in different builds of the 75 cards of Burn I’d built for the Pro Tour Magic 2015 Burn list I sent to Matt Sperling. The card just seemed absurd.

Of course, when it was printed, it simply wasn’t good enough. It might have been powerful, but in that moment, you could not afford to take the kind of time that Perilous Vault demanded. Taking off turns 4 and 5 would be unthinkable, and if you wanted to be a control deck, there were better ways to do it at the time.

But, like the Ashiok lesson above, things can change. Perilous Vault is a great reminder of that:

Do not shoehorn cards into decks because you love them; someday they may be good, but you can’t force it.

Before Sphinx’s Revelation rotated out, I loved Perilous Vault. But I didn’t play it until afterwards. Instead, I played U/W Control, Boros Burn, and Barely Boros Red Aggro. The card may have felt good to me at my core, but it wasn’t cutting it then.

Later, when things changed, I got the payoff of that first read. But I didn’t try to put my conclusion in front of my evidence.

While that was obviously my breakout list from a Pro Tour perspective, the breakout list from my career as a deckbuilder would probably be this next deck, Baron Harkonnen (sometimes just called “The Baron”):

Creatures (5)

Lands (23)

Spells (33)

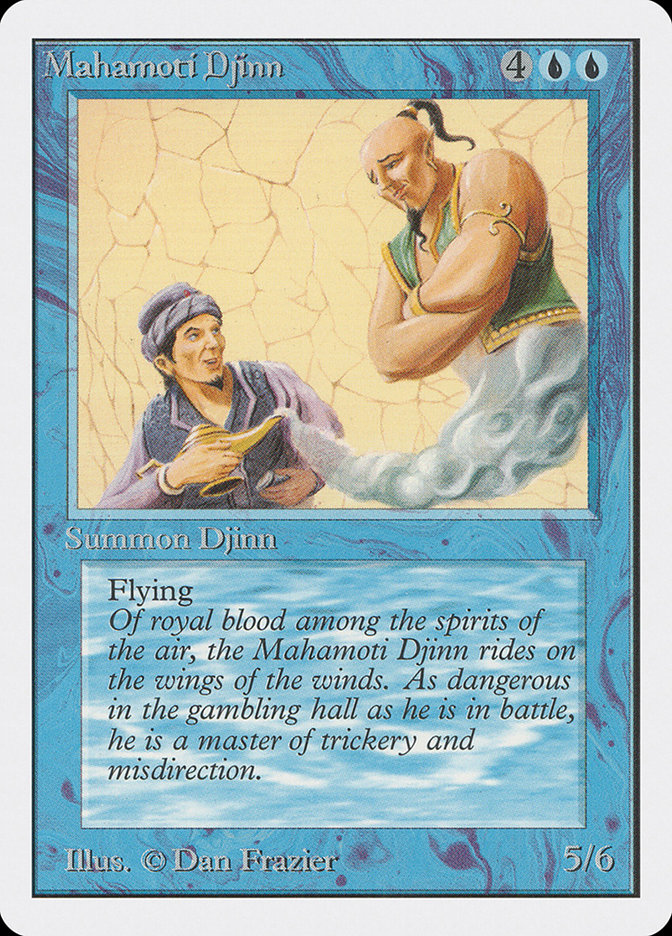

So this was certainly the era of odd deck names. In these early days of Magic, it was pretty common to have a deck name that expressed some inside joke or followed a naming convention (like the cereal convention for combo decks). This deck was named after “the flying fatman,” Mahamoti Djinn, aka Baron Harkonnen from Dune.

This deck, more than anything else, was the first culmination of the ideas of inevitability that I’d started to glean from the lessons of Gaea’s Blessing and, before that, Soldevi Digger. If your deck has sufficient inevitability and recursion, you can almost “teach” your deck how to beat your opponent in a kind of pseudo-AI. This can make you the de facto inevitability baron and make every long game basically approach impossible for the opponent.

Still, you need to kill the opponent.

The reason it is appropriate to name this deck “The Baron” rather than retrofit “U/G Control” onto it is that the deck not only has a pedigree in the history of the game but that it has that pedigree because of a philosophy we still see in play today. Having minimal finishers for a control deck was rare, but dropping them down to almost nothing was new.

In more recent days, we still see this in decks like U/W Control with a single Aetherling.

“The Baron” as a deck is about that recursive, AI-like control. “The Baron” as a card is the recognition that you need to kill your opponent; while it may be preferable to not have a “Baron” in your deck, sometimes you need a card that can just actively engage in a kill. To run a Baron card is to recognize that the whole point of the card is to dominate a late-game and win with it. This is different from a card like Elspeth, Sun’s Champion, which can also serve as a control card. “The Baron” in this sense is the idea that you must dedicate appropriate resources to your opponent’s demise.

I could have run without Mahamoti Djinn and just killed with Control Magic and Splintering Wind. It would be possible. In fact, in the finals of the PTQ I won, I killed my opponent with exactly one card: Splintering Wind. But in so doing, I’d be weakening the deck.

The lesson of The Baron:

No matter how “inevitable” your deck is, make sure you have enough ways to close the game.

Another card in The Baron that people related with me is one of my other favorite cards from all time, Sylvan Library.

I played this card in so many different decks that when I was looking for a column name back in the ’90s, my friend and Cabal Rogue collaborator John Shuler said, “Obviously, the name of the column is Sullivan Library!”

I still occasionally see this card in Legacy, and it warms my heart. It is an utter powerhouse of library manipulation and potential card advantage. If you have the life to spare, Sylvan Library is ready to become a Necropotence proxy. While there is plenty to be said about the card as a part of a strong library manipulation package that brings forth many of the same lessons as Gaea’s Blessing, perhaps more important to me was an entirely other lesson:

Life is a true resource in the game, just like card advantage and tempo.

Later, I’d codify this idea into what Mike Flores would deem my “Philosophy of Fire”, but this was one of the key moments, seeing Sylvan Library literally translate four life into a single card, and Natural Spring via Sylvan Library into two cards.

Of course, you can’t just give your life away four life at a time. You need to recognize that every time your life total drops, you are reducing your options in the game. A player with life to spare can make bigger plays because they can’t be punished for it. A player on the verge of death may be forced to not make plays, lest they potentially die on the spot.

I wouldn’t write about this topic until much later, and I discussed my theories on the topic with Flores and Zvi Mowshowitz around 1999, but Sylvan Library was what provided this very important lesson in the first place.

Ah, my favorite creature in Magic.

Creatures (19)

Lands (19)

Spells (22)

- 1 Umezawa's Jitte

- 4 Incinerate

- 4 Magma Jet

- 3 Shrapnel Blast

- 4 Molten Rain

- 4 Chrome Mox

- 2 Smash to Smithereens

Sideboard

Good ‘ol Dwarven Blastminer. The thing I love about this card is how incredibly unfair it is. When you’re dropping a creature that can so horrifically mess up your opponent’s game (potentially on turn 1 in this deck), it is worth paying attention to it. When you’re playing an unfair deck like this, a part of the reason the deck can be unfair is pushing some element of the game.

For a deck that includes a mana disruptive element like Ponza, it is hard to get any more unfair than Dwarven Blastminer, especially in a world filled with Zoo, Affinity, and Wizards. The lesson:

If you can do something unfair, see how far you can push that angle.

Putting Dwarven Blastminer in a deck with Magus of the Moon and Molten Rain is good to begin with, but adding in Chrome Mox to make it faster and sideboarding more mana disruption besides – you can just make things insurmountable. I would have run a fourth Dwarven Blastminer, but I felt like I needed every other card in the deck a little more, despite it being the real reason for the lesson.

There were many other cards that people mentioned besides these.

Paulo Vitor Damo da Rosa mentioned Orcish Librarian, a large handful of people mentioned Annex, Demonic Pact got a brief mention by several, Topsy Turvy was offered up by Charlotte Sable (albeit upside down), and Sphinx’s Revelation got the nod from a good handful. There were plenty more cards mentioned as well.

One of the things that I took great pleasure in with every card mention was thinking about what that card meant. In many cases, the card represented just a pleasurable memory, but sometimes, like in the case of Rorix Bladewing, it is a real-world example of an important concept; for Rorix, it is the understanding that, just because you sideboard something in for nearly every matchup, it doesn’t mean the card belongs in the maindeck.

Whether it was just a fond memory or something that inspired pondering about a great moment in my own journey learning about Magic, it was awesome engaging with people on the question of the meme. What cards do you associate with me? What card do you associate with you? Why?

The answers might give you something valuable to think about, if you care to take the time to reflect on it.