Worlds is over.

It’s been nearly three months since the Standard rotation. It’ll be another month or so before Mirrodin Besieged hits the scene.

The common refrain, even before Worlds, was that this is a “stale” Standard, stuck listlessly in place, waiting for an infusion of fresh cards to cause some turbulence and to wipe that dull, grimy layer from the surface to reveal another few months of interesting choices.

Is it stale?

Maybe, maybe not. The results from the Standard portion of Worlds — and the visceral, emotional response to seeing so many copies in the Top 8 — suggest that U/B Control has clearly floated to the top, dominating all other archetypes. As

Patrick Chapin just showed us,

this aura of dominance is a little suspect, perhaps more clearly reflecting good metagame choice instead. Contemporary U/B Control has a reasonable edge on Valakut, and Valakut was the single largest slice of the field.

It’s good to have an edge on one-third of the field, after all.

So, what do we trust? Do we trust the impression that U/B Control is now the dominant deck? Do we go with Patrick’s assertion that U/B is the only Tier 1 deck?

More to the point, how do we use the information we have to answer the only question that actually matters — what am I going to play this week?

Today, I’m going to talk about the whole point of metagame analysis, the most valuable things we can cull from it, and how we can use this information to pick the actual pieces of cardboard we’ll use to take down that next tournament.

What’s the point of all this, anyway?

So what’s the value of metagame information? What do we hope to get out of reviewing archetypes, how often they appear, what cards occur in them, and all the rest?

The answer to that question informs what kind of metagame data we actually collect — or, in my case, write about. Or, at least, it should.

Let’s take a few big ideas in turn.

The mythical matchup percentage

I always quirk an eyebrow when someone talks about how their deck is “55% against Valakut and 70% against U/W or U/B Control.” It’s not that they’re claiming dominance over the field; although we do like to do that when the design is our baby. Instead, it’s the deeply misleading specificity of a statement like “55% against Valakut.”

Really? 55%? How many games did you run to come up with that number? Against how many variations on the opposing deck, piloted by which players?

Now, we all know that the exact numbers are really notional — “55%” is often a way of saying “slightly more than half the time.” In

writing about Worlds,

Patrick is very clearly (and accurately) saying that players running U/B Control decks beat players running Valakut decks 55% of the time

during the handful of Standard rounds at Worlds.

Given these two possible meanings, I’d argue for actually saying what you mean. I’d even recommend sticking to saying things like “favored” and “massively favored,” because these words convey your meaning without misleading you into thinking you have especially accurate knowledge about which deck wins.

After all, even the Worlds data reflects the results from what is, essentially, a very select, slightly larger FNM. Six rounds with many of the players having qualified via National qualifiers that are smaller than any PTQ you’ve ever attended.

This brings up the second issue with the idea of matchup percentages — they’re kind of worthless.

One of my favorite “misunderstanding how life works” moments from a Magic tournament came during the opening announcements of an Extended PTQ a few seasons back. When our Head Judge announced it as a seven-round PTQ, the guy sitting across from me said, “Great! I only have to win five rounds. 1/32 odds aren’t bad.”

Cue brief pause, and then the player sitting beside me said, “It’s not random!”

Win percentages from prior tournaments tell us some very specific things. They let us know how some archetypes piloted by a given set of players performed against other archetypes piloted by other players. In some cases, this can help us do things like

make the case for banning a card

due to dominance in the format. However, what they don’t effectively do is help us decide which deck we should play or how we should tweak it for the next big tournament.

Like the guy beside me said at the PTQ, it’s not random.

If I tell you that I just watched fifty matches between Valakut and U/W Control, and Valakut won 60% of the time… should you play Valakut? If you play it, how should you play it? Which cards will optimize your chances in the next tournament?

The fundamental problem with this kind of information is that it’s not especially actionable. It’s a lot like an initial study that finds that type 2 diabetes is associated with obesity. It provides a guide for future work — whether that’s playtesting (Magic) or additional experiments (diabetes). You don’t just go ahead and slate every diabetes patient for liposuction in the hopes that it’ll cure them (pro tip — it won’t).

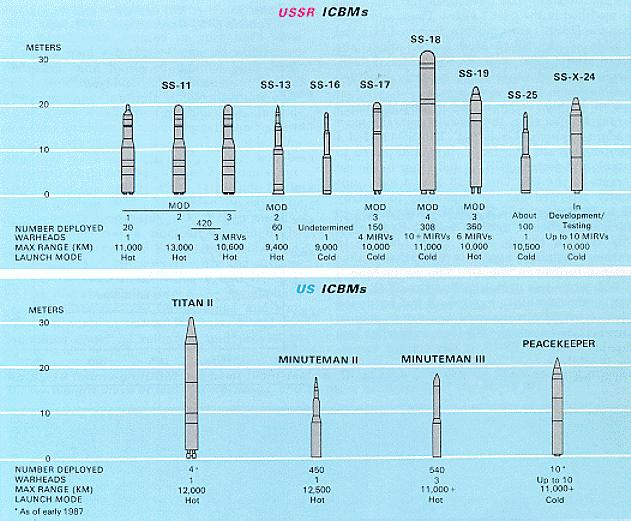

Soviet Military Power

While I was growing up, we had copies of

Soviet Military Power

lying around the house. Soviet Military Power was an annual review produced by the

Defense Intelligence Agency

that tried to provide an overview of the military capabilities of the Soviet Union.

And you were just reading

Greens Eggs and Ham

as a kid, weren’t you?

Soviet Military Power

was full of charts like this one:

Yeah. That’s a metagame breakdown of strategic nuclear weapons, circa 1985.

Soviet Military Power

had these charts listing the various weapons systems deployed by the Soviet military for one simple reason.

That’s what we had to beat.

Knowing what you have to beat is way more actionable than knowing how one archetype did against another in anonymous hands last week. Given a general impression of your likely opposition, you can start to make informed decisions about which archetype to play and what specific maindeck and sideboard choices you’ll want to make to maximize your likelihood of success.

Or, to put it another way, it’s more helpful to focus on the idea that you’ll face Valakut 60% of the time than it is to focus on how a bunch of Valakut decks, not run by you, performed against a bunch of other decks similarly not piloted by your future opponents.

In general, we want to be aiming for holes in the metagame. Consequently, the highest yield in terms of eventual success starts with figuring out what that metagame

is,

rather than how those components of the existing metagame interact with each other. Once we see

what we need to beat,

then we can start getting some use out of those notional matchup outcomes by using them as a guideline ahead of our playtesting.

The new hotness

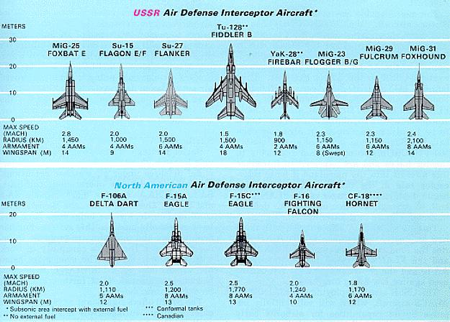

Here’s another image from the 1985 edition of

Soviet Military Power.

This time around, it’s not a metagame breakdown (the quantity of each plane shows up on a different table). Instead, it’s a sort of “deck tech” for American and Soviet interceptors. The numbers below each drawing tell us about the jet’s top speed, operational radius, weapons, and inexplicably, wingspan.

They are, essentially, “decklists” for combat aircraft. Obviously, this is sort of an overview, like listing the top cards in each deck, but it fits in with one of the major payoffs we get from pawing through metagame results.

New tech.

The holy grail of metagame trawling is the novel decklist that has shown up in tournament results but has somehow not yet made it into general circulation. Our dream scenario is to find this list way ahead of the curve and then profit until everyone else figures it out.

This isn’t entirely unrealistic. Yong Han Choo did it at

Pro Tour Hollywood,

coincidentally ending up in the Top 8 alongside the person he nicked the deck from, Makihito Mihara.

Of course, it helps to speak Japanese and know where results from 17-person tournaments are posted. In Japanese.

The more plausible version of this Holy Grail is to be an early adopter for a known list. Essentially, we look for a list that’s on the rise and hope to get in on the lower left end of the success curve. It’s sort of like playing the stock market where we hope to gain value even while everyone knows the list is good, then get out when the list becomes overexposed.

This doesn’t always work, though — Faeries remained dominant throughout the Lorwyn-Shadowmoor PTQ season, even though players

knew

it was winning tournaments.

Most frequently, though, we get value by checking out novel adaptations and card choices. Brian Kibler

Caw-Go

is essentially a U/W Control deck with a few major adaptations relative to the U/W decks that were prevalent before Worlds.

This aspect of metagame tracking is especially handy when we’re deep into a format — like the current Standard — and the question of innovation is no longer an easy one. Although it’s not impossible to develop an entirely novel deck this late in the cycle, it’s very hard, and you’re going to have to put a lot of time into staring at Gatherer, scribbling notes, and hoping those lateral connections start to form in your brain until you develop the next Magical Christmasland.

Applied metagaming

So I’m clearly most interested in using metagame data to figure out (1) what we have to beat and (2) what new tools might be around for us to beat it with. How does that apply to today’s “stale” metagame?

The opposition

The question of “what we have to beat” is never as straightforward as it seems. Back in the days of

Soviet Military Power,

there was significant debate about how accurately those facts and figures reflected the overall power of the Soviet military. Could they really deploy all those weapons? Did they have more of certain ones than we realized?

We tend to assume, because it’s the easiest thing to do, that the metagame is the same all around the world. Magic Online reinforces this belief, since it is effectively the biggest gaming venue in the Magic world, and you can’t really identify different internal metagames, so it’s one gigantic metagame.

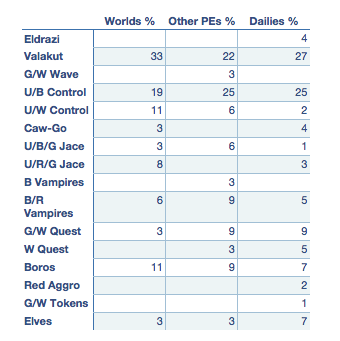

But the metagame isn’t universal, and our store’s FNM metagame is different from the Worlds metagame which is different from the StarCityGames.com Open Series metagame… and so on. Consider this breakdown of recent metagames:

The “Worlds” column reports on all decks scoring 15+ points at Worlds in Chiba (I cut out the 13-pointers). The “Other PEs” column reports on Top 8 decks from two MTGO PEs, the Standard PTQ at Worlds, and another Standard side event at Worlds, for a total of 32 decks. Finally, the “Dailies” column reports on 4-0 lists from 28 MTGO Daily Events, comprising 107 lists.

If Worlds defines our metagame, then we should expect a solid third of our opponents to run Valakut, followed by a fifth running U/B Control, and with Boros and U/W Control making a reasonable showing at ten percent each. In contrast, the PEs and Dailies give us a lower percentage of Valakut, a much higher percentage of U/B Control, and a crushing absence of U/W Control.

My suggestion would be to take your target metagame into consideration and then squint your eyes, and form your aggregate picture of that metagame from all of these potential data sources. Given that approach, a notional “top five” list of target decks in Standard might look like this:

1 — U/B Control

2 — Valakut

3 — U/W Control (let’s wrap Caw-Go up in here)

4 — Quest variants

5 — Boros

Notice that this isn’t a list of the

most effective

decks in Standard. I agree with others that Quest decks aren’t very good.

But that isn’t the point. The point is that enough people

bring them

and enough people

win with them

that you must be prepared to beat them if you want to win. Even if G/W Quest has universally abysmal matchups, if you ignore it completely, you’re opening yourself up to auto-losing against a deck that you should easily roll. Or, if it’s not that severe, you at least risk giving your opponent better odds of winning than they’ve earned with their deck choice.

Or, to put it another way… sure, U/B Control beat Quest decks

over two-thirds of the time

when they met at Worlds. But does

your

build of U/B Control beat Quest decks?

This is why, at least for me, “what I need to beat” is king, at least when we’re using metagame data to help decide what to play. Because even if you and everyone you know think Quest decks suck, about one in eight Top 8 slots at recent mid-sized events went to Quest decks anyway. If you wanted to win one of those events, you needed to have a deck and a plan that beat Quest.

As always, you need to be able to bias your own target list based on the level and location of the event you’re planning for. If I were going to a StarCityGames.com Open Series event sometime soon, for example, I’d add U/G/x Jace lists to my target pool on the premise that higher-level players who attend Open events prefer Jace decks a lot more than your random player.

Survival of the… oh, wait, not that

When we first learn about evolution, we naively assume that it means that nature finds the

perfect

solution to every problem.

As it turns out, no.

The cauldron of natural selection leads to solutions that are “good enough.” After all, life is the ultimate “graded on a curve” situation — if you make more babies than the species next door, it doesn’t matter how far you are from being the best ape you can be. You did good enough.

We intuitively apply the same attitude to contemporary Magic. After all, there’s MTGO, and everyone has Internet access. Shouldn’t we expect the metagame to be “solved” a few months in?

Again, not so much.

There are forces entirely outside of “absolute optimization” that can let a deck dominate a metagame. If a player has a very successful list, for example, why would they try to develop a new one? In recent weeks, U/B Control has proven itself “good enough” for many players. In the same vein, using a known list buys you all the development work that has already been put into it by many other players. There’s a positive feedback loop at work here where more players pilot the deck, the deck is further refined, then it sees more play and success, and this loop repeats itself.

So, the upshot of all this is that a deck isn’t automatically awesome because it sees a lot of play, and it isn’t automatically terrible just because it hasn’t been widely played.

Here are some of the decks I’ve seen in this latest metagame roundup that took the road less traveled and may offer some insight into how you can take down your next Standard tournament.

Creatures (31)

- 4 Llanowar Elves

- 4 Elvish Archdruid

- 3 Nissa's Chosen

- 4 Arbor Elf

- 2 Joraga Warcaller

- 1 Wolfbriar Elemental

- 4 Joraga Treespeaker

- 4 Fauna Shaman

- 2 Ezuri, Renegade Leader

- 3 Copperhorn Scout

Planeswalkers (3)

Lands (19)

Spells (7)

This is a fairly stock Elves list but for the addition of two copies of Asceticism in the main and a third in the side. I was initially skeptical of that card, especially on top of three copies of Eldrazi Monument in the maindeck. However, this deck subscribes to the principal of “if you’re going to do something, do it to excess,” and in testing, it was amazing to see how powerful the mass troll shroud could be. Given how much Valakut and U/B Control rely on spot removal, it just might be worth investing five mana and a card slot into making all your little dudes invulnerable.

Creatures (13)

Planeswalkers (4)

Lands (27)

Spells (16)

Remaining in the land of subtle changes, this U/R/G Jace list inverts the distribution of Acidic Slime copies you’ll see in most stock Jace builds. It’s one of those small changes with the potential for profound impact — and it mirrors the maindeck Ruinblasters Dan Jordan used to great effect a month and a half ago at the

Boston Open.

Acidic Slime ends up being a “Ruinblaster update” here, sacrificing some speed for the ability to trade in combat with Grave and Frost Titans. Although it would be too slow to beat Dan Jordan Ruinblaster-wielding U/R/G, the good news for this design is that Acidic Slime’s five mana is plenty fast when the opposition is banking on six-mana Titans for the win.

Creatures (17)

- 3 Baneslayer Angel

- 4 Stoneforge Mystic

- 2 Student of Warfare

- 4 Squadron Hawk

- 2 Sun Titan

- 2 Molten-Tail Masticore

Planeswalkers (7)

Lands (25)

Spells (11)

Sideboard

I tagged this as “U/W Control” when I tallied the two Standard public events at Worlds, but it’s far from what we’d think of when we hear the name. Sure, it has many of the usual suspects — Sun Titan, Mana Leak, Oust, and the ubiquitous Jace. It also adds in everyone’s favorite bird quartet, as seen in Caw-Go. But then it veers even farther away from stock U/W Control by using the Hawks to power Molten-Tail Masticore, running quad Stoneforge Mystic to allow access to double Sword of Body and Mind, and topping that off with two copies of Student of Warfare as well as triple Baneslayer Angel living in the main rather than the sideboard.

So what is this deck, really? At a glance, it seems like a midrange deck, being something not quite a control list and not quite pure aggro. However, it’s a very powerful midrange deck if so and one that gets a lot more mileage out of the already very abusable Squadron Hawk than most of the decks that use it.

Creatures (17)

Planeswalkers (3)

Lands (24)

Spells (16)

What if we just smooshed a bunch of our favorite decks together into one big deck?

At a glance, this deck violates some of the rules of using its constituent cards. Running Genesis Wave instead of more big creatures dilutes the value of Summoning Trap. At the same time, running those Traps — as well as Cultivates, Explores, and Condemns — dilutes the potential value of those Waves.

These things are both true and less important than I thought they’d be before testing. After trying the deck out for a bit, it retains the potential to go crushingly over the top with either spell despite the potential for negative interactions. I suspect it would, with additional testing, “calm down” into a deck that can even more effectively maximize the value of its core power cards while culling cards that genuinely detract from both strategies (those Condemns, for example).

Bringing it all back in

Formats are almost never as stale as we say they are. Calling a format “stale” gives us an excuse to check out — the same kind of checking out that has us fail to playtest a matchup because the opposing deck is “bad.”

People play bad decks; people lose to bad decks.

The best deck, the dominant deck, is never the perfect deck.

This week, right now, we need to beat a handful of archetypes if we want to win, and the tools to do so just may be waiting in last week’s decklists, or may be up to you to develop.

***

parakkum

on Twitter

magic (at) alexandershearer.com