Why Kobe Bryant is Basically Volcanic Hammer

“Morphling is Michael Jordan. He plays offense. He plays defense. He goes over the other team to score, he takes the charge when they try to score… and keeps going in the playoffs. He is the all-star. Masticore is Charles Barkley. He’s expensive. He isn’t always pretty. Sometimes he spits in people’s face. But he gets the job done. Palinchron is the fat, overpaid, free agent. When the chips are down, he is looking out for himself. He doesn’t play offense and defense. He has a big scoring game sometimes, but has a huge contract. You don’t want him on the team.”

—Patrick Lennon Johnson, from “Silver Bullets” (by me!)

Believe it or not, I did not actually invent using basketball analogies in Magic articles last week. The above is from Patrick Johnson, the creator of Accelerated Blue, critiquing the various creatures you could play in that seminal deck.

Last week’s Flores Friday—which opened up on my “modern” thinking process rooted in the disconnect between “conventional wisdom” / fan-grounded basketball analysis versus a statistically-driven / much-more-representative understanding of the production of delta baskets—had lots of things going for it. For one, some people seemed to like it, even if they didn’t necessarily like the “basketball” bits; others liked the in-Magic equivalencies that re-center our analysis on mana value versus cards and wanted more; while still others understood what was going on from the basketball perspective and appreciated the vast expanse between what “most people” think they know about basketball versus the actual processes that lead not to scoring lots of baskets (which seems like “a good thing” until you put it into context) … but to scoring more points than the opposing team, which is the actual goal of the game of basketball.

The conclusion I drew in that article was that generating more possessions (assuming a typical ability to convert possessions into points) is generally more productive than just taking lots of shots.

The disconnect, which is what drives some fans crazy, is that the media—and indeed free agent contracts—all focus on the latter, which is why prolific scorers are so well paid (and generally well regarded) whether or not they help their teams win.

In a kind of happy accident, that very night my beloved Cleveland Cavaliers visited the Los Angeles Lakers… and were defeated.

The game was on LA time, so I decided to go to bed at the half, when my Cavs trailed an essentially insurmountable 41-59.

The next morning I was not surprised to read the following commentary on the ESPN recap, though I must say it is the single most asinine piece of non-analysis I have ever read in my life, and the poster child for why no one understands nothin’, good effin’ god.

“The Cavs had absolutely no answer for Bryant, who went 15 for 31 with four 3-pointers and six turnovers.”

Let me rephrase that a moment:

“The Cavs had absolutely no answer for a player who shot less than 50% from the field but elected to spend 40% of his team’s entire possession count while also turning the ball over an embarrassing number of times by any measuring stick.”

The media was perhaps understandably obsessed with Kobe Bryant’s nth consecutive 40-point game, even stating the Cavs had “absolutely no answer” for him… but that is obviously not the case. Don’t get me wrong; even with six turnovers Kobe had a fine game by most measurements; that said, he actually under-performed relative to every other Laker who played significant minutes, except with regards to the number of shots he was willing to try to get on the highlight reel. Pau Gasol (a top 5 NBA player who was the actual MVP of those last two Laker titles) shot 9-16 (56%) and produced ten rebounds and four assists. Pau did not turn the ball over once. Matt Barnes shot 50% from the field and was 5-5 from the free throw line, scoring fifteen points on ten shots, pulling down four rebounds, and taking care of the ball better than Kobe in every conceivable way. Andrew Bynum, the All-Star Center, shot SEVEN-of-nine (77% my lord!), pulled down eleven rebounds and blocked three shots. Bynum was like Dwight Howard Junior in this game. Now that’s a stat line! The really impressive thing about the last two Laker titles is that they started Derek Fisher at the point (who could not play, let alone start on, the majority of sub-500 NBA teams). Fisher blew as usual (his main contributions being handing the ball to Kobe and crossing his fingers ten times), but the truth is, Kobe did nothing outlandish save take a million shots (or 31) that were all less efficient than those taken by every non-Fisher Laker / starter who played significant minutes.

The notion that the Cavs couldn’t answer him is ludicrous. If anything, they had bigger problems with Gasol, Bynum, and even Barnes. Yet Kobe just kept shooting the ball, hog-style, in order to get his usual media mention.

Couldn’t answer him?

They forced him to turn the ball over six times.

Couldn’t answer him?

The Cavs were down 18 points when I went to bed. Game was over, right?

Final Score: Cavaliers 92, Lakers 97

FIVE points.

HOW IS THIS POSSIBLE?

“The media” apparently has no idea what makes a game go, points at a 41-point performance, and tells you it is awesome, when in fact it is perhaps fourth-best on the team.

Kobe Bryant, in short, was the Los Angeles Volcanic Hammer.

Volcanic Hammer, by the by, is a perfectly good Magic card. I have written several articles about how playing Volcanic Hammer over Magma Jet could throw off an opponent—even allowing you to beat the “unbeatable” Life with RDW. Patrick Chapin cited its speed and redundancy over Last Gasp as pivotal in his winning the 2007 Regional Championships, and it was in Standard and Extended both, a favorite of Patrick Sullivan and Tsuyoshi Fujita. Volcanic Hammer, then, must have been better than the vast majority of played Magic cards in its era, to have been productive in so many different decks and ways…

It is just in contrasting it to Incinerate or Lightning Bolt we disgust ourselves. Against a squad of Stoneforge Mystics, Jaces, more Jaces, and Kor Firewalkers, Volcanic Hammer might not have been the best; but against a rebuilding team shooting .2 worse than the worst team in the league, at the end of a seven-game West Coast stretch and repeated back-to-backs?

Volcanic Hammer is just dandy.

That said, how did the Cavs stay so competitive? (A five-point game, by the way, is highly competitive.) … You probably already know. The Cavs generated 9 more shots on 8 more rebounds than the Lakers. [They basically tossed up mono-Gut Shots.] They also turned the ball over 18 times. [Apparently they didn’t know when and when not to use the Phyrexian mana cost on those Gut Shots.] Even worse, the main problem is that they [Gut] shot a disgusting 37% (20 basis points worse than the average for the 30th place Sacramento Kings—the worst shooting team in the National Basketball Association) on this particular night. It was the end of the longest road trip of the year, and their jumpers just didn’t fall that night.

But the fact is, the Cavaliers are not two-time NBA Champions one year removed, and they spent most of last season setting the record for most consecutive losses by an NBA team. There is no expectation for them, but at present, they are good enough for a playoff berth in the East! At a flaccid 40% shooting (below their average, the league average, and what the Lakers allow statistically), the Cavs would have beaten the mighty Los Angeles and prolific Bryant by about 4 points.

Ever wonder where the great PT players go when they disappear from the tournament standings but reappear on Facebook draped in bikini models, revving up cherry-red Challengers?

Good at gaming…

Good at math…

Hmmm…

This also explains, by the way, why some people are so successful at sports arbitrage and the other 99.5% of people lose badly, betting. The idea of what is good—and how players are compensated—is just wildly off of reality, and as with Magic technology, the quality of information that drives the mechanics of your thought processes, strategies, and ultimately decisions is going to prove quite telling in your results.

Write this down:

“There are only two kinds of people, those with ‘reasons’ and those with results.”

Sadly, New York fans (some of whom are good friends of mine) think that the Knicks should be title contenders in 2012. They have assembled their Miami-challenging Big Three. After all, they have two of the most prolific scorers in recent years—Carmelo Anthony and Amar’e Stoudemire—and added the proximate reason the Dallas Mavericks won the NBA Championship last year—Tyson Chandler—in the off-season. Tyson Chandler, by the way, is playing arguably even better than Dwight Howard so far this year!

But in reality, the Knicks have an even worse sub-500 record as my deservedly maligned Cavs and a substantively inferior point differential (the Knicks actually have a negative point differential!) … How can that be, if Chandler was such a great addition (he absolutely was) and they have such supernatural talents—that is scorers—as Melo and Amar’e?

You guys already know.

Okay, the preamble to this article was as long as most non-Patrick Chapin articles.

Point being, our focus in Magic cannot be on the generation of possessions. Unfortunately Magic turns, barring Final Fortune, Time Stop, et al, don’t come as a result of rebounds and turnovers as they do in basketball. However, we are still limited by them.

Back in the 1990s, thinkers like Eric Taylor and Brian Weissman distilled the turn into two base symmetries:

- Draw one card per turn.

- Play one land per turn.

Later, shall we say Next Level thinkers pointed out there are other fundamental symmetries to the turn, such as the untap, the attack phase, and so on. Yet most of our strategy originates from the above two symmetries, which is why most Magic theory follows the lines of drawing more cards (Weissman) or playing more lands / mana (Mowshowitz).

As we discussed last week, one of the things that I like to work on in terms of selecting cards is to get cards to do more measurable stuff for me without paying more mana for it (Countersquall over Negate… or I suppose Incinerate and Lightning Bolt over Volcanic Hammer) and focus on mana—rather than cards or damage (but rather cards and damage, acceleration, and life gain / defense as equivalencies based on their relative value in mana).

That is a great starting point, but what it doesn’t address is the notion of spending the possession. Like, why isn’t a Volcanic Hammer many times better than a Cursed Scroll? A Cursed Scroll deals two damage with a minimum four-mana investment; Volcanic Hammer does three for just two. What gives?

|

vs. |

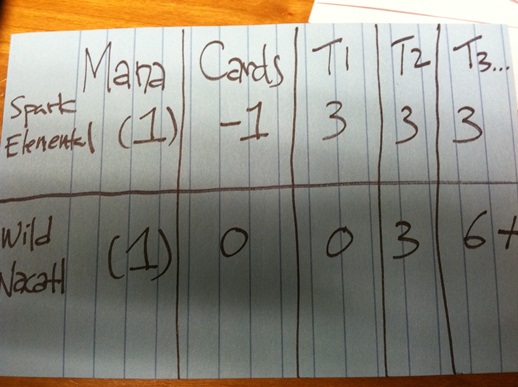

Which is a better card, Spark Elemental or Wild Nacatl? That is kind of a silly question. PT Top 8 competitors like Pat Cox and Sheriff Wescoe have declared themselves wilder and wilder still Nacatls, for life—forever—whereas I don’t know of any PT Top 8 competitors self-identifying as Spark Elementals. Wild Nacatl was just banned in Modern whereas Spark Elemental is barely playable, and then, only in one deck.

Is that good enough for us?

What if we look at it a little bit differently?

Saying Wild Nacatl is the better purely on “reputation” is the same as saying that one ball player is better than another simply on reputation / lifetime points production. Certainly after 2-3 turns of attacking, Wild Nacatl is putting up more damage (0, 3, 6+ etc.); in addition, Spark Elemental costs you a card all by its lonesome, and Wild Nacatl is essentially cards-neutral but zone-traveling (goes from your hand to the battlefield).

On the mana they both cost one.

If we consider one mana equivalent to two damage, then Spark Elemental (provided it hits) is 50% above the curve. Wild Nacatl may at some point be many times above the curve but not for the second turn out, at least. There are lots of times you would rather have a Spark Elemental rather than a Wild Nacatl. It certainly isn’t “a fact” that Wild Nacatl is “a better card” than Spark Elemental. What might be useful is to figure out when each is appropriate.

You will have noticed by this point I have focused on the notion of possessions and considered one of the above discussed cards in a different costing light than the other, all inspired by bball.

The curve:

- Shock

- cycling a Lonely Sandbar

Above the curve:

- Lightning Bolt; possibly Burst Lightning and Galvanic Blast

- Brainstorm, Preordain, Ponder, Gitaxian Probe (woah Gitaxian Probe); possibly Visions from Beyond

Note that while a Burst Lightning or a Galvanic Blast might be “strictly better” than where we set the bar, for practical purposes they often operate exactly at par, getting essentially nothing out of that strictly better-ness.

Now if you hit someone with a Spark Elemental, its performance relative to the equivalencies-driven expectation for its mana is “above the curve” (again we are focusing on results rather than “reasons”). Wild Nacatl, the turn it comes down, has not done anything… but it only cost you mana, not a card. In that sense, it is possible for almost any creature to perform above the curve. Hit someone five times with a Squire? Above the curve. See how hard it is for bad creatures to perform above the curve, even with the discount afforded by not using a card, but how relatively easy it is for a Wild Nacatl?

A creature like Goblin Guide is really interesting.

Its expectation, immediately, on the first turn is at-curve… but like Wild Nacatl, Goblin Guide has no inherent cards price tag. However, because Goblin Guide helps the opponent draw extra cards 40% of the time, it can potentially bleed mana at the same time. This way of thinking explicitly shows us why a Goblin Guide is so great on the first turn, on the play, but mediocre mid-game.

You spend a mana, get in for two (on-curve); your opponent draws an extra card (worth a mana in theory) but can’t use it (zeroes out). Later in the game, the opponent might have fewer than seven cards in hand (so he can keep the card) and might have substantial defenses allowing him to negate the Goblin Guide’s desired two damage. That said, all of its downside is still present if you want to attack.

Ultimately, and in dealing with Modern at present, I have two overarching concerns.

First up, let’s look at some historical decks and see what we can extrapolate from them:

Creatures (10)

Lands (22)

Spells (28)

- 4 Hymn to Tourach

- 4 Duress

- 4 Sarcomancy

- 4 Cursed Scroll

- 4 Dark Ritual

- 4 Sphere of Resistance

- 4 Demonic Consultation

Sideboard

Total Mana Cost: 56

Average Mana Cost: 1.47

//

“Deck to Beat” of Combo Winter – High Tide

Lands (21)

Spells (39)

- 2 Stroke of Genius

- 4 Brainstorm

- 4 Counterspell

- 4 Force of Will

- 4 Impulse

- 1 Intuition

- 4 Merchant Scroll

- 4 Frantic Search

- 4 Turnabout

- 4 High Tide

- 4 Time Spiral

Sideboard

Total Mana Cost: 113

Average Mana Cost: 2.90

//

Kuroda-Style Red

Creatures (8)

Lands (24)

Spells (28)

- 4 Sensei's Divining Top

- 1 Sowing Salt

- 4 Magma Jet

- 3 Beacon of Destruction

- 4 Pulse of the Forge

- 4 Shrapnel Blast

- 4 Wayfarer's Bauble

- 4 Molten Rain

Sideboard

Total Mana Cost: 103

Average Mana Cost: 2.86

“Deck to Beat” of Standard – Tooth and Nail

Creatures (16)

- 4 Sakura-Tribe Elder

- 3 Vine Trellis

- 1 Kiki-Jiki, Mirror Breaker

- 1 Triskelion

- 1 Mephidross Vampire

- 3 Eternal Witness

- 1 Sundering Titan

- 2 Viridian Shaman

Lands (21)

Spells (23)

Total Mana Cost: 131

Average Mana Cost: 3.36

//

Critical Mass

Creatures (17)

- 4 Sakura-Tribe Elder

- 1 Isao, Enlightened Bushi

- 4 Meloku the Clouded Mirror

- 4 Kodama of the North Tree

- 4 Keiga, the Tide Star

Lands (23)

Spells (20)

Total Mana Cost: 119

Average Mana Cost: 3.22

//

“Deck to Beat” of Kamigawa Block – Gifts Ungiven

Creatures (16)

- 4 Sakura-Tribe Elder

- 2 Ink-Eyes, Servant of Oni

- 2 Meloku the Clouded Mirror

- 1 Kokusho, the Evening Star

- 1 Myojin of Night's Reach

- 1 Hana Kami

- 1 Ghost-Lit Stalker

- 4 Kagemaro, First to Suffer

Lands (23)

Spells (21)

Total Mana Cost: 119

Average Mana Cost: 3.22

//

Sideboards!

Critical Mass – 38

Gifts Ungiven – 46

//

Naya Lightsaber

Creatures (25)

- 4 Ranger of Eos

- 4 Wild Nacatl

- 4 Woolly Thoctar

- 4 Noble Hierarch

- 4 Bloodbraid Elf

- 4 Baneslayer Angel

- 1 Scute Mob

Planeswalkers (3)

Lands (24)

Spells (8)

Sideboard

Total Mana Cost: 93

Average Mana Cost: 2.58

//

“Deck to Beat” of Standard – Jund

Creatures (16)

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (25)

Spells (17)

Sideboard

Total Mana Cost: 107

Average Mana Cost: 3.06

//

Exarch Twin

Creatures (11)

Planeswalkers (6)

Lands (26)

Spells (17)

Total Mana Cost: 97

Average Mana Cost: 2.85

//

“Deck to Beat” of Standard – Caw-Blade

Total Mana Cost: 86

Average Mana Cost: 2.53

I just thought of a couple of decks where I played or designed a deck that produced outstanding results and measured that deck against its era’s deck to beat.

On every occasion but the most outrageously good deck in the history of Standard, across huge formats like Combo Winter Extended to tiny formats where the cards are all pretty much the same (though we did have to go to sideboards based on the massive crossover in playable spells), I found the same thing, over and over and over:

When I can distinguish myself via superior technology, that comes with cheaper spells and lower overall aggregate mana costs. It is only—only—in the age of Caw-Blade that this is not true. This is true from my first PTQ win (I presume my Necropotence in a format where Necropotence wasn’t cool out-hustled R/W GargleHaups with all one-, two-, and three-mana spells relative to their all five- and six-mana spells, but the decks are lost in Brandon Sanderson’s Mists). Napster pushed Replenish down the stairs 87 to 103 and 2.35 to 2.94; while Jushi Blue bobbed and weaved around Gifts Ungiven by a 103 to 118 and 2.94 to 3.19; Brian Kowal’s Lightning Angels annihilated the ponderous seven- and eight-drops of Solar Flare by an embarrassing 114 to 146 and 3.08 to 3.95.

Era after era after era.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I think we have a Magic theory.

(Unless you happen to be the greatest deck of all time.)

Challenge #1

Now that we know, the challenge is to put that knowledge into the best practice that we can. The first thing I did was to cut two Cryptic Commands from my Modern deck and replace them with two Countersqualls. While Cryptic Command is powerful, it is hard to even quantify how much you are getting out of it. Let’s assume that you get a card and a card (Dismiss mode) that is worth [whatever the card is worth] plus one mana but costs you four mana. This isn’t even a very good deal on its face, and we don’t know what the initial card was worth, making the mathematics woefully awkward. Now let’s assume we are trading with a Countersquall. Different (and in fact narrower) possibility of cards we can be countering, but still a card, and often a more pivotal one (Jon Finkel told me he loves playing against Cryptic Command with Storm, it is so bad)… two damage—two life loss—is also wortha mana in our schema.

This tiny switch allowed me to 1) lower my overall mana by four and 2) my per-spell cost by a little more than .11; simultaneously I—for often the same effect, but again the counting is quite nebulous based on the quality of the opponent’s effects—am getting essentially the 3) same value for 4) half the price. Non-absolutely we are also talking about a discount of colored mana on the order of 33% and overall intra-card costing of 50%.

Here’s the challenge:

Go find the deck you like and figure out where you can lower your absolute and / or average mana costs. Cards like Ponder (above the curve!) are obviously great at this. They allow you to recover mana you wouldn’t otherwise spend on uneven turns, and they are operating above the curve anyway. These cards—cheaper if less Kobe-like in their total production—are improving on your admittedly “perfectly fine” suite of Volcanic Hammers.

Remember blah, Blah, BLAH, Multipliers, and Using Every Part of the Buffalo? Tweaks like this fall under the “multipliers” column. And the cool thing? There are all kinds of places we can employ better and better strategies to yield better results.

Challenge #2

Once I figured this out, I decided to go out and do something about it. I was going to PTQ tomorrow in Brooklyn (local), but it turns out that I have “family day” at my son’s school + brunch with an old college roommate, so oh well on that front.

This is what I would have played:

Creatures (12)

Lands (20)

Spells (28)

- 4 Lightning Bolt

- 4 Magma Jet

- 4 Molten Rain

- 4 Blightning

- 4 Searing Blaze

- 4 Geth's Verdict

- 4 Bump in the Night

Sideboard

It’s doing well for me. I intentionally went out of my comfort zone and tried very hard to play multi-dimensional threats while forcing my curve down.

I can’t say enough about Geth’s Verdict. I have won games just by using it as a bad Fireball for one, plus it does a fine job of killing Emrakul, the Aeons Torn!

It seems weird to have been bragging about Terminate in a three-color deck… and then not playing it at all in a two-color black-red one. The weakest card is Searing Blaze; I think I would have tried Rift Bolt there (Rift Bolt being more practically flexible + cheaper in most games, Searing Blaze being somewhat cost- and opportunity-prohibitive but having a massive upside). I found the three-mana cards very good. They give the B/R some card advantage / oomph that is not present in the Shard Volley decks. I tried very hard to play cards that operate above the curve (e.g. Lightning Bolt) or trade up (Geth’s Verdict) or both (Smash to Smithereens).

GL if you are playing tomorrow!

LOVE

MIKE