Dragon’s Maze Limited—even the very strange triple DGM Draft format—has been a blast so far, but even those of us who are highly addicted to opening boosters end up playing Constructed once in a while. Last weekend I headed to a moderately sized Standard tournament (about 120 people).

Having not played Standard very much since the format’s rotation, I decided that the safe bet would be to take a known deck (Chris VanMeter G/B/W Reanimator) and run it card-for-card, making a few minor adjustments to the sideboard to account for the metagame’s shift to slightly more aggressive. To this end, I simply added some copies of Elderscale Wurm and Devour Flesh to the sideboard to combat the increasingly disturbing presence of Aura-based decks. I also considered Bruna, Light of Alabaster to blank their primary strategy, but in the end Elderscale Wurm did the same job just as well without Bruna’s glaring weakness to Invisible Stalker.

The tournament started off on a promising note, with a win in the first round, but the wheels fell off soon thereafter. In the second round, I was paired against Bant Flash, which should be a fairly easy matchup. Their primary threat is a 5/5 token, and the Reanimator deck has a number of ways to remove such a token or to preclude its very existence (Fiend Hunter and Angel of Serenity being key, but Thragtusk and Sin Collector do a great job as well).

After whiffing on several copies of Grisly Salvage in a row, I packed it in for game 1, and I had a similar experience in the second game, consistently revealing additional copies of Grisly Salvage, a copy of Mulch or two, and perhaps a land. The deck in effect was playing like a suboptimal midrange deck—I was able to use the spells that I drew, but I never did anything "unfair" or gained any value out of the graveyard enablers.

In general, I don’t tend to tilt from losses like this one, but it was a frustrating experience to lose a pretty solid matchup. Still, I wasn’t particularly affected by the loss—until a helpful bystander decided that this would be a perfect opportunity to "mansplain" to me how the Swiss pairing system worked. I left the area, got a drink of water, and took a deep breath. At no point did I raise my voice or complain outwardly, but something about the situation was not entirely thrilling.

As I sat down for my third round, I’d gotten myself fairly well in check. I asked my opponent if he would like to "high roll" for play/draw privileges, and he agreed. I rolled a six on a six-sided die. My opponent looked down at the six on the die, looked up at me, and said "I’m sorry, I don’t do one-die rolls. You could be cheating."

If I hadn’t quietly tilted at this turn of events, I would have called a judge to mediate here.

But I was tilted, so I didn’t. I rolled a second die, and it was a one.

I offered him my dice, which he declined, and he pulled a separate set of dice out of his bag. He won the roll and played first. I’m sure I could have played differently, but I lost a very close game by half a turn.

Whenever we lose a game by half a turn, especially in Standard or Limited, it is likely that we could have done something different to win the match.

But I wasn’t focusing on that. I was thinking about the dice. Without another thought, I kept a one-lander with Avacyn’s Pilgrim and two Mulches the next game, blanked on my first Mulch, conceded, and dropped from the tournament.

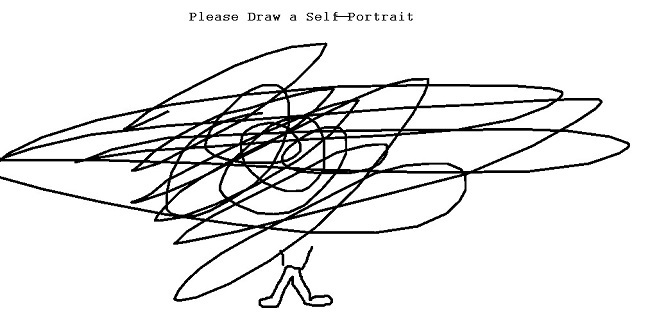

If I were asked at that moment to draw a self-portrait (ignoring that I’m totally incapable of drawing), it would have looked like this:

This got me thinking about tilt.

There are a lot of great Magic articles about tilt (many of them published on this very site). Most articles that focus on becoming a better Magic player likewise have at least a minor emphasis on tilting.

I began to wonder if anyone had ever done quantitative or qualitative research examining tilt and success at card games—aside from what’s available in various books—and I was pleasantly surprised by what I found.

In 1989, Basil Browne published an article in the Journal of Gambling Behavior called "Going on Tilt: Frequent Poker Players and Control."

First, let’s put this into perspective. The year 1989 took place in a totally different world than 2013. Magic didn’t even exist and wouldn’t for four more years. Celebrity participation in poker tournaments to the extent that we see today simply didn’t happen. Online poker tournaments for cash? Nope. The author of this article was writing about "California card rooms"—a very different world.

At the same time, many of the concepts advanced in the article are similar to what we observe today in modern Magic and poker play. The term "tilt" already was in existence in the 1980s to describe a variety of negative phenomena exhibited by card players, and there was apparently a comparable term for the same behavior pattern, "steam" (the Betamax of poker terms), that has fallen out of favor.

Although the primary focus of Browne’s article is problem gambling, much of the content applies to us today. He wanted to establish "tilt" as a "grounded theory," meaning one that can be used to predict, explain, and research behavior.

"Gambling becomes a problem for players who are on tilt frequently. Problem gamblers’ careers are characterized by tilting… All frequent card players go on tilt. It’s usually while players are on tilt that they lose large amounts of money. Players can go on tilt for periods ranging from minutes to days and, on occasion, for months" (p. 11).

So then what constitutes tilt? "The term tilt implies a deviation from a norm. One’s game or play and one’s emotion state are the base lines" (11).

Interesting. All frequent card players go on tilt. That’s something that makes a lot of sense, but it’s easy to assume that the best players never have the impulse to get upset or react adversely when something unexpected happens in their match.

So what do these initial findings tell us? First, there are multiple components of tilt. Not only do we have the frequently observed emotional response (leading us to scrawl random drawings instead of a portrait), but we also experience actual differences in game play. The two things are linked.

In fact, Browne’s work researching others who have examined the phenomena explores the preliminary idea that tilt actually mirrors a "dissociative state." Whereas previous research had suggested that tilt is an issue of impulse control (12), Browne suggest that it’s actually best explained using a control theory.

In other words, it may be a bit simplistic to suggest that the solution to tilt—the way to regain our solid emotional foundation and resume playing at a normal level—is simply to work to accept that "bad luck" is part of the game.

Instead, we conceptualize tilt as a deviation from the norm—both in terms of our gameplay and in terms of our emotions. While Browne does acknowledge that some players have unusually extreme reactions (he doesn’t mention throwing a deck or flipping a table, but I’ve seen Magic players do both), he says that in most cases, "Players do not deteriorate to that point. Rather, their play gradually deteriorates as they struggle to gain control" (12).

He suggests that the "tilting process" is a three-part phenomenon.

Initially, there is the "tilt-inducing situation." In Magic, it can be the improbable fourth Lightning Bolt off the top of our opponent’s deck or the singleton Notion Thief dropping in response to a Brainstorm on camera.

Then, there is a period where we attempt to regain control.

Finally, if we are unable to immediately regain control during the internal struggle, we begin to play worse to some degree (and what Browne does not note but I have observed is that by playing worse we are at higher risk for additional situations that potentially might tilt us because we don’t recognize our own culpability in creating adverse situations).

It’s important to realize that tilt isn’t just a product of "bad beats." It can also occur quite easily as a result of what Browne calls "needling—a direct attempt by players to annoy or upset fellow players" (13). While this is incredibly prevalent on Magic Online (and don’t get me started on League of Legends, where the sign-up package includes a free-to-play champion and an unspoken agreement that everyone else playing the game would actually prefer that we die a horrible death), I don’t see a lot of it in paper Magic.

However, there can still be verbal exchanges that are frustrating. For example, I don’t think that the player who attempted to introduce me to the Swiss pairing system was trying to be offensive—it was ultimately my own decision to let that process frustrate me given that the player didn’t do anything "wrong."

So what can we do to avoid tilt? It isn’t clear that there is a secret formula to avoiding it entirely (otherwise it already would be marketed on the sidebars of our Facebook pages). Browne does, however, offer some advice:

"Consistent winners feel the frustrations and annoyances, but they do not let them affect their game… They do emotion work to suppress and shape those feelings and emotions. Consistent losers, on the other hand, often deny or ignore such feelings…

Consistent winners are aware of situations that have the potential of putting them on tilt, are alert for those situations, and have built up a cognitive focus, a rationalization that can get them off tilt…

Some consistent winners are so proficient doing emotion work that they report not even hearing the conversations of needlers…" (16-17).

So while there is no "secret" to avoiding tilt, there is a strategy—one that involves conscious practice and awareness. It’s interesting, at least to me, that it is ineffective to try to ignore frustrations and annoyances (a behavior observed generally among those who lost frequently). Instead, players who manage tilt well are those who can manage the frustrations and annoyances while learning to ignore potential sources of annoyance. (Note that this is different than ignoring the emotions. To use a simple metaphor, consider the difference between ignoring a taunting pitcher in baseball versus refusing to swing at a perceived "bad pitch.")

One additional component of successful card players that was not mentioned in Browne’s article but that pops up twenty years later in the International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction in an article by Griffiths et al. (2010) is the idea that successful players "do not overestimate the skill involved in poker" (85). This fits very nicely into the tapestry created by Browne’s work—if tilting often is a reaction to an unexpected bad beat, then our emotional mismanagement of our response may stem from an overestimation of what we could have done.

There are some games that simply cannot be won, and while good players always attempt to discover what they could have done differently, there are undoubtedly situations that cannot reasonably be expected or predicted. If we overestimate how much control we have over the mechanics of the game, we run the risk of tilting ourselves as well.

Here’s the overly simplistic, TL;DR summary of the article: if we start tilting, we shouldn’t ignore or disregard our emotions. Instead, we should practice controlling and managing them.

This isn’t revolutionary (especially since much of this research was conducted fifteen years ago), but there is a subtle difference implicit in this information that might help some of us improve our game.