Over the last couple weeks, Standard has reached a very defined and stable state. We see the same four decks at the top: Mono-Blue Devotion, Mono-Black Devotion, G/R/x Monsters, and decks built around Sphinx’s Revelation. These are supplemented by a rotating cast of several other known decks as the metagame shifts.

What makes the format tick? Why are these decks the ones that we see consistently populating the top tables?

1) The Power Level Of Creatures Jumps Drastically At Two & Four Mana

The following hyperaggressive one-drops are legal in this Standard format:

Only one of them (Cloudfin Raptor) sees reliable play. Aggro is at best a metagame call.

The issue is that these cards match up terribly against the available two-drops:

The vast majority of the available two-drops brick all of the one-drops or at the least trade extremely favorably for them. Sure, there’s the occasional bad matchup like Pack Rat on the draw, Sylvan Caryatid versus Firedrinker Satyr, and the multicolored guys against Soldier of the Pantheon, but most of the time your one-drop gets in at best one hit on the play and zero on the draw.

Now let’s look at the three-drops:

Some of them fight the two-drops pretty well, namely Boros Reckoner. Still, that’s just "some" of them. Frostburn Weird trades with basically anything here. Tidebinder Mage taps down half of the cards listed. Pack Rat goes above and beyond these cards. Fleecemane Lion can go over them as well. Thassa, God of the Sea and Domri Rade require assistance to even enter the fight

What the three-drops do that the two-drops don’t is gain value. All of these give you the ability to generate card advantage, albeit very loosely with Loxodon Smiter. Notice how the most successful three-drop at any given time is the one that generates the most cards against the target deck, whether it is Nightveil Specter, Domri Rade, or Lifebane Zombie. Thassa, God of the Sea is the exception since it is always amazing, but Thassa is only playable in one archetype and dictates around 50 of the other cards in your deck, whereas the above options are more flexible.

What about the four-drops?

Well then.

Sure, Lifebane Zombie can take some of these, but once on board the four-drops trump all of the three-drops (ignoring an active Thassa, God of the Sea). Boros Reckoner is at best a trade.

If you play a three-drop in this format, the window where it provides a dominant board presence closes almost immediately. Most of the time the only ones that end up mattering are those that provide evasion.

At five we have the following:

I wouldn’t argue that any of these are necessarily worse than the four-drops, but they don’t immediately halt their attacks the way the fours stop the threes and the twos stop the ones.

Past five you start running into mana curve issues. It’s hard to actually hit your first six land drops while doing enough early things to not be dead. Even if your six-drop does trump everything below it, the odds it lands on curve to swing the game back in your favor are low. Considering the size of all of the above creatures, that one turn is often the difference between life and death. Elspeth, Sun’s Champion might be able to do it, but almost nothing else can.

So what does this mean?

As mentioned above, aggressive decks are not very good. The other archetype that suffers is aggressive midrange. For an example of this, look at Eric Froelich’s Pro Tour Gatecrash Top 8 deck.

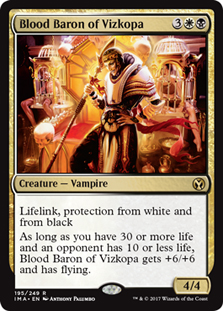

In this format when a deck that plays permanents wins, it does so from a board state that is nearly insurmountable. Killing your opponent and having the "still have all these" is rare and mostly related to mana screw or the case where one of the high-end threats is something they actually can’t handle, like Blood Baron of Vizkopa with a chump sacrifice back against Mono-Black Devotion.

2) Midrange Means Mana Problems

So we’ve determined that if you want to play permanents in this format, you have to play midrange of some sort. Your curve is going to be focused on two- and four-drops, with potentially three- and five-drops that are difficult for certain matchups to beat.

In order to reliably cast your spells, you need to play at least 24 lands. If you have five-drops, you probably need more.

The fact that your most powerful spells cost four also creates bottleneck scenarios. You cast one threat a turn, and then your opponent responds with one threat. Assuming you are both on the same level of four- and five-drops trumping everything else, it’s hard to pull ahead on tempo.

As a result, mana flood and mana screw are amplified. Missing your fourth land for a turn means they get ahead one four-drop. Drawing an extra land while they draw an extra four-drop means they get ahead one four-drop.

This is why Temples and Mutavault are so important. Temples help prevent both flood and screw, but the more subtle part of Temples is that the curve structure of the format plays right into them. If one-drops and three-drops aren’t required parts of a curve, spending a mana early to scry costs very little. Also, because your curve flattens out in power at four, having to spend another turn playing a four instead of a five is not typically game ending. As for Mutavault, it’s just worth a card. While it won’t typically trade for a four-drop, it can double up with a low drop to trade for one, putting you ahead in the four-drop count, or just chip away after everything else has been attritioned away.

Note: Sequencing flexibility was one of the big draws to Dredge. The ten mana accelerants, two-mana Nemesis of Mortals, bestow, and eight two-mana dig effects provide a wealth of good options every turn beyond the "which four-drop is better" debate most of the decks in this format have. You can get ahead a tick in the midgame and afford to miss on a draw step while your opponent struggles to pull out from behind. Also, Nighthowler, Nemesis of Mortals, and Shadowborn Demon are some of the midrange threats that actually break parity in these fights by just being bigger and forcing two-for-ones. Despite not having access to an on-guild Temple and not having room for Mutavault, the deck can still put up a fight.

3) Conditional Removal Costs Two, Unconditional Removal Costs Three

This is what two mana buys you:

All of these fall short in certain categories. Some of them are flexible or provide card advantage but are terrible at killing four-drops. Some of them kill four-drops but fail to hit the full spread of high drops. Some of them handle everything but only temporarily.

As a side note, basically none of these kill Obzedat, Ghost Council. The card shines when removal dominates, but when threats are the focal point, it is average and overcosted.

At three you see Detention Sphere and Hero’s Downfall that kill pretty much anything. You also get Dissolve, which answers actual everything with the right timing

What does this mean?

Detention Sphere and Hero’s Downfall are great and are incentives to play their color, but they are still expensive enough that you can’t really gain tempo off of them.

Four-drops can be handled in a tempo-profitable way with removal spells, but you have to guess right for the metagame. Each threat isn’t better than the answers, but the group of threats as a whole tends to make it hard for the person supplying the answers to find the correct ones.

If people start overloading on removal, the five-drops come out to play.

4) Options To Rectify Board States Are Mostly Limited To "Play Something Bigger"

You get behind on board or behind on cards. How do you pull out of the tail spin?

Umm . . . well . . .

Assuming you’re behind on the four-drop level, it’s really difficult. Your four-drops might be good against theirs, but that’s matchup dependent. You might get them with Detention Sphere, but again that’s conditional.

There aren’t many cards that pull you back into a game in this format by providing grinding advantages. There’s no Cryptic Command, Bloodbraid Elf, or Thragtusk to build up two-for-one advantages.

With enough mana, Sphinx’s Revelation can do it, but given how hard the four-drops hit, you often have to be moderately stabilized to recover with it.

Things like Trostani, Selesnya’s Voice and Chandra, Pyromaster can generate grinding advantages, but again due to the size of the four-drops, they will not help you fight from behind.

Elspeth, Sun’s Champion can do it, but again that card costs a significant amount of mana.

Lifebane Zombie and Tidebinder Mage can create this two-for-one advantage but are color specific. That said, getting hit by one of these cards is typically pretty devastating and almost a reason to not play the color green. Or at least not play green creatures that cost more than three.

The card that rectifies a board state for reasonable amount of mana without just being the biggest thing around is Supreme Verdict.

We’ve laid out the rules of how the format operates. How does each of the best decks take advantage of these conditions?

Esper Control

Esper Control leans heavily on the fact that it gets to play all three of the best game-swinging cards: Supreme Verdict; Elspeth, Sun’s Champion; and Sphinx’s Revelation.

As a result of playing so many cards that can do this, Esper has the privilege of playing more than its fair share of Temples. Even though the format is extremely favorable to tapped lands, there’s still a limit. If it’s hard for most decks to come back from being midgame behind, you have to hit your midgame drops on curve. Esper can ignore this limit since it can recover from midgame disadvantages.

Esper’s heavy reliance on removal also helps make up the mana difference. If your threat costs three or four and my response costs two or three, I can "spend" that mana earned on a Temple.

Mono-Black Devotion & B/W Midrange

Black has relied on one of the few cards that lets you get ahead early: Pack Rat. In exchange for being slightly behind on curve, Pack Rat levels up all of your previous drops to match the curve. This puts you ahead multiple midrange-sized threats going into turns 5 and 6, which as mentioned above is pretty insurmountable.

Black also makes heavy use of one of the few card advantage engines in the format: Underworld Connections. While it isn’t the best option, it lands at an empty slot on the curve (three) and lets you out-threat them going late.

That said, threat density is one of the big reasons for the push toward splash colors. It’s not like you wouldn’t have Temples anyway, so the extra color is nearly a freeroll. Mono-Black Devotion basically just has Pack Rat and Desecration Demon as singlehanded game winners. Gray Merchant of Asphodel can kill people, but it typically requires board dominance to do so. White offers Blood Baron of Vizkopa and Obzedat, Ghost Council as top tier threats alongside the unique stabilizing effect of Elspeth, Sun’s Champion. On the other hand, red offers Rakdos’s Return, which can in theory trade for multiple four-drop threats.

Mono-Blue Devotion

Mono-Blue Devotion operates almost entirely on the assumption that Thassa, God of the Sea and Master of Waves are better than the rest of the format’s threats. Thassa is a three-drop threat that when active matches or exceeds any other threat, while Master of Waves can overwhelm most other threats in a heads-up fight.

The tradeoff is that you have to dedicate slots to cards that don’t fight the four-drop battle to enable your threats. The only reason this deck works is that the few cards available to it that do this can manage to do things as your opponent slams four-drops at you. Tidebinder Mage might take something down, Frostburn Weird trades up for three-drops, and the rest of your creatures have flying so that you might just get there on damage.

G/R/x Monsters

Monsters just tries to play its four-drops a bit faster than everyone else. It aims to regain the card advantage lost to playing small creatures as additional lands via planeswalkers.

The problem is that it isn’t actually that good at doing these things

Polukranos, World Eater doesn’t actually win any four-drop fights, and Stormbreath Dragon doesn’t either. Against all of the non-Esper decks, planeswalkers rarely run away with a game. Even against Esper, you are facing a deck with a significant number of ways to handle them.

Black gives you Rakdos’s Return and Reaper of the Wilds. Return can let you stop multiple of their four-drops, but odds are they drew more than you did to start with because their deck isn’t two-thirds mana. Reaper can help you find more threats, but it doesn’t actually win any fights.

Monsters is basically the Level 0 deck based on these fundamentals and as a result only really capitalizes on decks that don’t play to these rules.

R/W Burn

Burn ignores all of the rules and instead makes the following supposition:

With people obeying the standard of "four-drops are what matters," they will goldfish around turn 7, turn 6 at best. I am betting that my completely non-interactive clock will win the game before that.

My issues with the current iterations of this archetype are the following:

- The first supposition is not really accurate. There are a lot more ways to die on turn 5 than the deck would hope. Master of Waves, Pack Rat, and Nighthowler can all easily close games out. Also, the lack of one-mana burn spells significantly slows the deck down relative to previously successful burn decks.

- You’re relying a lot on drawing the proper land to spell ratio. Besides Chandra’s Phoenix, your cards all do the amount of damage they say on them. While this is a known issue with burn decks, this list magnifies it. Because your spells all cost two or more, you have to play 23 lands. You’re playing Chained to the Rocks because you don’t have enough cards. You’re also playing Shock. Burn in this format is significantly more inconsistent than it should be as a result.

- There is more interaction than you would like. You have Skullcrack, but it has to line up. Decks have Thoughtseize, Duress, Dissolve, and life gain.

Naya Hexproof

Naya Hexproof assumes that a seven-power first strike, hexproof, lifelink creature is better than the other available threats in the format and also completely untouchable. For the most part, it’s right. When Supreme Verdict is involved, things get dicey.

Mono-Color Aggro (Red, White, & Black)

All of these decks operate under the same principle. They hope their opponent is ignoring the "two-drops beat one-drops" part of the format. If they are, your one-drops should run them over. If they aren’t, you resort to the Mono-Blue Devotion plan of hoping some amount of evasion bridges the gap. Black has Herald of Torment, Spiteful Returned, and Mogis’s Marauders. White has Brave the Elements and a couple of Time Walk in Imposing Sovereign and Banisher Priest. Red has Chandra’s Phoenix and burn spells.

I’m going to be realistic here. If your opponent is playing two-drops, you aren’t winning with Mono-Color Aggro. Mono-Blue Devotion, Naya Hexproof, and Mono-Red Devotion will all wreck your day. Even some of the three-drops are near impossible to beat, namely Boros Reckoner and Courser of Kruphix.

But if the metagame has devolved into a bunch of Esper Control or Mono-Black Devotion decks that aren’t brick walling your team until later, it might be time to sleeve up one-drops.

G/B Dredge

Dredge operates in a similar manner to Mono-Blue Devotion. Nighthowler and company are card for card significantly better than the other threats and worth dedicating the rest of your deck to cards that enable them to work. Shadowborn Demon also breaks the fourth rule, allowing you to Shriekmaw your way back into the game.

Your enablers do a lot of work as well but in a different manner than the blue ones. Instead of providing a semi-relevant board presence, they find your game winners. If each of your threats is worth two of theirs and you draw your threats just as often as they draw theirs, you tend to come out ahead.

So where is this all going?

Knowing the landscape, what are the things we should be looking for to change the format?

Find a card that breaks this set of rules.

We’ll go through these one by one.

We aren’t likely to find a one-drop that outclasses the available two-drops unless Deathrite Shaman 2.0 gets printed, but a three-drop that matches up well against the four- and five- drops is within range. It’s also reasonable that a four- or five-drop threat gets printed that drastically outclasses the others. It’s reasonable as well that some pure two-for-one style card gets printed that changes the base dynamic of the format, like a Bloodbraid Elf.

A new archetype could also be created that is completely non-interactive, like R/W Burn. You could further create an archetype that can reliably generate threats that are bigger than the four- to five-mana range. An example would be the Junk Reanimator deck that has been floating around, which is just a little too inconsistent. Still, cards like Ashen Rider, Luminate Primordial, and Angel of Serenity create sweeping advantages that aren’t really matched by most decks in the format. Of course, you could also argue that Esper Control is the deck that currently does this with Elspeth, Sun’s Champion and Sphinx’s Revelation and that any deck cheating permanents into play is hard pressed to have better support spells than Esper’s pile of answers.

The mana isn’t going to get much better, but additional mana sources that generate value might be printed. If a Mind Stone, Noble Hierarch, or man land gets printed, the deck that gets to best utilize it gains a lot.

Removal is also in a tricky spot thanks to the various protection from color abilities on the four- and five-drop threats. I can’t imagine Go for the Throat being reprinted, but something on that level would be needed to shift the two- and three-drop removal set points of the format. If the metagame shifts in a specific direction, look to capitalize on that by finding the removal spell that fits the threat set, or if a new three-drop answer gets printed, look for the deck that gains additional coverage from it.

As for things that rectify board states, remember that they have to cost five or less mana to really work. If there’s a secret Shriekmaw, let me know, but otherwise we’re waiting until Journey into Nyx for this one.

Plenty of people are still brewing for this Standard format. Better yet, Journey into Nyx is just around the corner. Just remember, when you brew, do so with purpose. Doing new things is cool, but doing new things for a reason is how you win.