Howdy gamers, and welcome to the second week of another run of the Magic Online (MTGO) Vintage Cube! I’m thankful to say that I’ve been drafting more in paper than online these days, but even with that and logging entirely too many hours on Pokémon Unite I was able to snag a couple of trophies last week. We’ve been going over some more nuanced strategies for drafters on The 540, and today I’ll be addressing how to assess the sorts of cards that you should try to wheel in the MTGO Vintage Cube.

In case you’re unfamiliar with the term, “wheeling” a card from a pack refers to the second card you take from that pack. For example, “the wheel” from Pack 1, Pick 1 is Pack 1, Pick 9, when you see what came back to you from the pack that you opened after the other drafters have had a crack at it. I’ve written a lot about first picks in Cube, but knowing the sorts of cards that you should attempt to draft on the wheel can be just as important to drafting a successful Cube deck.

My criteria for first picks tend to be cards that are the best versions of an effect, cards with high value over replacement in the decks or colors that perform well in the Cube, and cards with low opportunity costs. As such, my criteria for cards that I try to wheel will unsurprisingly be cards that fall short on these qualities. That doesn’t give you the whole picture though, so I’ll break things down into a few different categories of cards that I try to wheel along with some examples of cards that fit each category in the MTGO Vintage Cube.

High Mana Costs

Generally true in Cube, but especially true in Vintage Cube, you want a lean mana curve with a lot of cheap cards. The game can run away from you very quickly if you’re not casting much on the first three turns of the game. The most obvious application of this criterion comes when drafting aggressive decks. When a pack presents you with a choice between two on-color creatures, you should almost always take the cheaper option. Flickerwisp has some cool applications, but not enough to be all that meaningful over other three-drops and definitely not enough to shy away from drafting as many one-mana creatures as possible. Early in a draft I’d take Thraben Inspector over Flickerwisp every time, and in this specific comparison I’d generally stick with that pick order later in the draft as well.

This principle is a little less obvious when it comes to drafting slower and more controlling decks, but it’s just as important there. Controlling decks in Vintage Cube can decimate even the most broken Vintage Cube decks, but they have to be able to cast their spells on time. Cheap counterspells and cantrips will do a lot more for your deck than having the specific four-mana card that you want. Control Magic and Fact or Fiction are two four-mana blue cards that will almost always make my deck, but space for four-mana cards runs out much sooner than space for cards like Ponder and Counterspell, so I will generally draft those cards over them.

With some regularity I discuss spots on the mana curve of the Cube that are really glutted. When it comes to red and white cards that cost four or more mana and green cards that cost five or more mana, I will err on the side of taking a cheaper on-color card over them until I get to the point where I’m late in the draft and my deck is lacking top-end. Things generally don’t play out that way though, because I’ll take as many of the cheap options as I can get and there’s enough of the expensive stuff to get something on the wheel with regularity.

Low Rates of Play

This was a major talking point between Justin and me on The 540, and is probably the best reason to try to wheel a card as opposed to picking it highly. If there’s a card that you would happily play in your deck but that isn’t a high pick or generally playable card in most decks, then you should realistically draft a card from the pack that will make your deck that other players would more likely want to play as well.

To illustrate the sorts of cards I’m referring to, let’s take a look at one of my 3-0 decks from last week:

Creatures (19)

- 1 Llanowar Elves

- 1 Birds of Paradise

- 1 Fyndhorn Elves

- 1 Deranged Hermit

- 1 Acidic Slime

- 1 Lotus Cobra

- 1 Arbor Elf

- 1 Avenger of Zendikar

- 1 Joraga Treespeaker

- 1 Avacyn's Pilgrim

- 1 Craterhoof Behemoth

- 1 Whisperwood Elemental

- 1 Nissa, Vastwood Seer

- 1 Tireless Tracker

- 1 Elder Gargaroth

- 1 Magus of the Order

- 1 Toski, Bearer of Secrets

- 1 Ignoble Hierarch

- 1 Circle of Dreams Druid

Planeswalkers (1)

Lands (14)

Spells (6)

Looking at this list, you can see what I mean about there being too many green five-drops, but those aren’t the cards that I want to draw attention to. Magus of the Order and Circle of Dreams Druid are two cards that significantly improve the quality of this deck but that I would not expect anybody at the table to want to draft.

Circle of Dreams Druid is basically impossible to cast, and it was an easy choice to take Ignoble Hierarch over it in Pack 1. These decks want as many one-cost mana creatures as they can get, after all. It also wasn’t at all surprising when the Druid came back around, though it was reassuring when it did wheel, as this made me more confident that the lane for the green ramp deck was open. When I saw Magus of the Order in Pack 2, a card that I would play in the overwhelming majority of my green ramp decks, I knew that I could pass it for a cheaper card and that the Magus would come back to me because it goes in exactly one style of deck.

It’s unlikely that I would cut either of these cards from my Mono-Green Ramp deck, but it’s even less likely that anybody else at the table wants them once I have established that this deck is open. Some good comparisons on these lines would be seeing a Sulfuric Vortex once you’ve established that Mono-Red Aggro is open, or an Adanto Vanguard for Mono-White. You should be able to confidently pass these for the Lightning Bolt or Swords to Plowshares that other players are more likely to want and to end up with both when the pack comes back around.

These are very specific examples that have pretty clear answers, and more generally you’ll want to be asking yourself how many decks want a specific card, and how likely it is that somebody at the table is in one of those decks. The more specific the application of a card, the more likely you’ll see it on the wheel.

The only caveat I would make is when the narrow card in question is a marquee card for the deck you’re drafting. With the green deck posted above as an example, I would never pass Craterhoof Behemoth once I established that I wanted to draft this deck, because the difference between having it and not with all of the tutor effects is massive. I had a Terastodon in the sideboard of that deck, which is fine, but it doesn’t offer the deterministic closing power that Craterhoof does, and you just can’t gamble with that sort of thing.

Second-Best Versions

This is probably most true in a powered Cube, but you’ll definitely run into this phenomenon in any 540-card Cube. It’s simply the case that a number of the cards in the Cube, however playable, are just worse versions of other cards in the Cube. If you can make an argument regarding hedging on a land or card to try to branch into a different archetype over taking a card that is a worse version of something else, I would almost always do that and then try to wheel the worse something else.

A few years back, I cut all of the Incinerate effects from Grixis Cube due to how bad it feels to have them when other players are casting Lightning Bolt and Chain Lightning. Not all cards are created equal, but when you’re doing the same thing and doing a worse job of it, you’re going to be in trouble more often than not. It’s unrealistic that the second-bests of the Cube will be valued highly by anybody at the table, and if you’re taking them aggressively it will typically come at the cost of a better card in that pack because you should be able to get these cards on the wheel.

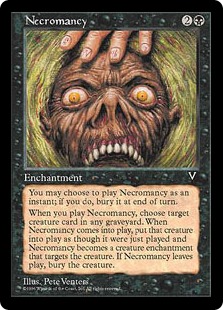

Necromancy and the B-tier Reanimator cards are a great example to illustrate this point. The best Reanimtor deck includes Entomb, Reanimate, and Griselbrand. Beyond that, you’ll have some redundancy on all of these effects — enabler, reanimation spell, and reanimation target — but they’ll all be downgrades from these three cards. The rest of the deck ideally consists of card selection spells, tutors, and cheap cards that offer some battlefield presence and/or interaction. Baleful Strix does more for a good Reanimator deck than Necromancy, and if you feel compelled to take the second-rate cards for the deck, you’re in the wrong lane. Always set yourself up to wheel the second-best versions of cards.

Another spot where you’ll see a high volume of second-bests in a Cube is in the lands column. In fairness, on-color lands that enter the battlefield untapped are broadly interchangeable, but the lands that most commonly exist in Vintage Cube as second-bests are creature-duals. Given how much the format is about mana development, it’s more common that these lands punish you for entering the battlefield tapped than reward you for having an activated ability. If it’s late in the draft and I really need some fixing for my Sultai deck, I’ll reluctantly take a Hissing Quagmire highly, but as a general rule creature-duals live on the wheel.

The rule of second-bests also applies to the aforementioned Magus of the Order as compared to Natural Order. I’ll play Magus of the Order in my Craterhoof Behemoth deck almost every time, but it’s much more likely to wheel than the superior Natural Order. Even if I’m actively interested in the card, if I have a look at a card that is the best version of something else that I can play, it’s generally better to try to wheel the former.

You Need Something Else More

Finally, a reason that you should try to (or at least hope to) wheel a card, even if it would be very good in your deck, is that your deck just needs something else more. Decks that stick to one or two colors don’t need much mana fixing and can largely abide by the rule of taking the cheapest and best things, but when your deck needs a higher volume of mana-fixing or is trying to enact multiple gameplans your pick order gets trickier. As an example, a deck that I really like in the MTGO Vintage Cube these days is Sultai Midrange. Here’s a look at a 3-0 list of this archetype that I drafted over the weekend:

Creatures (15)

- 1 Birds of Paradise

- 1 Eternal Witness

- 1 Looter il-Kor

- 1 Riftwing Cloudskate

- 1 Venser, Shaper Savant

- 1 Acidic Slime

- 1 Sheoldred, Whispering One

- 1 Baleful Strix

- 1 Pack Rat

- 1 Ophiomancer

- 1 Reclamation Sage

- 1 Kitesail Freebooter

- 1 Hydroid Krasis

- 1 Woe Strider

- 1 Archon of Cruelty

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (14)

Spells (9)

This deck has four core components — mana acceleration, threats, interaction, and mana fixing. The key to the success of this archetype is making sure all four of these components are well-represented. During the draft I got cards across all three colors that I was happy playing and the Mox Jet in Pack 1, but I didn’t get any mana fixing. Even the finished deck was still rockier than I’d like on mana-fixing lands, and as such during Pack 2 you would have had to have clawed that Prismatic Vista and those fastlands out of my cold, dead hands. This deck does have a good spread of threats and interaction, but for the most part the only thing it’s doing better than other decks on average is in the mana acceleration department.

There are some strong cards here, but the deck is scrappy in some respects and just making sure that I had enough points in the mana fixing, threats, and interaction departments was the key to success in this draft. Once I saw that I wasn’t getting any mana fixing late in Pack 1, that was all I needed to know to take it over almost anything in Packs 2 and 3. I’m not saying that Control Magic is a bad card by any stretch of the imagination, but after taking the mana fixing early, I was able to wheel it and would have realistically played whatever other four-mana card I got there.

The ideal outcome of drafting a given Cube pack is to get the two cards that you most want to draft from it. This rarely happens in practice, especially in Vintage Cube, but you can pretty often end up with two cards that you’re happy playing, and if you can consistently do that, you should be able to consistently draft solid decks and win matches. Being aware of the sorts of cards that you should try to wheel goes a long way in this department, and I hope the information I outlined today helps you in doing so.

Happy Cubing.