The New Capenna Championship may go down as an important event in the broad history of competitive Magic and one that exemplified all that’s good and bad about this era of Organized Play. As someone who participated in the tournament and assumed my usual position glued to the coverage in between my own rounds, I’ll try to offer an inside and outside view of the event.

End of an Era

This weekend was the final event in a season that was in itself the end of a radical experiment for competitive Magic. For those members of the Magic Pro League and Rivals League who saw that concept’s potential collapse around them and gritted their teeth as they collected their check, this was their final professional obligation. We learned last year that professional Magic is officially dead. This was a fitting sendoff.

For some, this marked the end of their personal involvement in this level of play. Without the seat at the table reserved for League members, players who didn’t qualify for the first paper Pro Tour via their record in this tournament will have to fight for those slots at their local Regional Championship with everyone else. If you had other obligations or opportunities, from parenthood to a mainstream career, this was a firm cue to focus on those instead.

The security and continuity of those invites is what allowed some to dedicate themselves to the game as fully as they have. The first Pro Tour of the new system will also be the first Pro Tour in many years that luminaries like Paulo Vitor Damo da Rosa or Gabriel Nassif aren’t automatically qualified for.

It’s no coincidence that many of these announcements or threats of retirement come from players in regions historically neglected by Organized Play. As the Pro Tour returns to paper, the reality of geography is thrown back into sharp relief. The Japanese players who dominated the online era had to set their alarms for an ungodly hour to compete in these tournaments, but they could still do that from the comfort of their bedrooms. If the Regional Championships is just a glorified Pro Tour Qualifier for your area and the Pro Tour itself lacks its former cachet, how many players will travel to the other end of their region to claw their way back?

Heavyweight Champion of the World?

As the last event of the season, the stakes were higher than ever. The final seats at the World Championship were awarded this weekend.

There has always been heated debate over the criteria for those invites. Previous efforts to ensure a truly global feel to the World Championship and acknowledge the stark geographical disparities baked into competitive play by assigning slots for top performers by region proved controversial. Specific roles like Grand Prix Master, which Brian Braun-Duin won to book his ticket in 2016 and earn his title of World Champion, encouraged even more criticism. The other extreme of just taking the top point earners across the year is more superficially neutral but still lacks something.

The qualification system this year reserved many more slots for Challengers, a weight class that was already guaranteed to be less competitive, and didn’t apply a multiplier to points earned before the Top 8. As a result, attendance trumped everything else; just qualifying for each Set Championship was the easiest path to the World Championship. Nathan Steuer, one of the best players in the world and a worthy champion of it, qualified via back-to-back-to-back 9-7 finishes – an individual record that wouldn’t even earn you an invite to the next Set Championship! The Set Championship Qualifiers took on absurd stakes for anyone who had accumulated points but not invites – several apparent win-and-ins for Worlds took place in the finals of otherwise unremarkable third-party tournaments.

If you want an illustration of how warped this was, consider that I was close to qualifying for Worlds! After not even playing in the Innistrad Championship, a pair of 9-6 finishes at the others left me one win away from a tie and two from an invite. It’s hard to feel any regret about not qualifying because I couldn’t claim with a straight face that I was one of the best players in the world this year, but part of me wonders what could have been.

Meanwhile, the competition for the League slots at Worlds was amazingly intense and was likely to come down to a single match late on Saturday – which makes it all the more gut-wrenching that it was decided by poor tournament management.

That wouldn’t be the only complaint this weekend…

Missed Connections

Any online event run remotely is vulnerable to internet issues or other localized problems outside the control of anyone involved. The test of a digital client and a tournament organizer is how well they respond to those issues. Both were found wanting here.

After two years of hosting high-level tournaments on MTG Arena, the program still has no clean way to handle even brief disconnections in a tournament setting and there still seems to be no clear attitude among tournament officials about how to handle these situations. I played in the first and now the last online equivalents of the Pro Tour two years apart; that tournament experience has improved considerably, but during events like this it often seems like nothing has been learned or changed since then.

Nassif and the other French players weren’t the only unfortunate victims here. On the Sunday stage, games were still being decided by issues that could be laid squarely at Arena’s feet. In particular, David Inglis lost his match against eventual winner Jan-Moritz Merkel as a result – an outcome that may have changed the entire story of the tournament.

For players accustomed to paper play who had to suffer through the Arena era, these are even more perfect examples of why they can’t wait to pick up some actual cardboard again.

Other players have experienced competitive Magic mainly or exclusively through tournaments like this on Arena and come to these with a background in other games that play by their own rules. If you only play any of the digital-only card games that unofficially compete with Arena in this space, the idea of an in-person tournament sounds harmlessly quaint until you think about the logistics. You’re really going to force everyone to gather in the same physical location, hire a small platoon of event staff to handle all the additional burdens that only exist in the tabletop game, and take on all the risks to tournament integrity that an online client removes?

As a proud paper boomer, I have to be honest about how much I take for granted about it – the possibility of explicit cheating as well as accessibility, card availability, and everything else. It’s fair to criticize Arena for not having a way to handle disconnections during tournaments after two years, as long as we acknowledge that issues like slow play have plagued paper Magic for decades now. As this new generation of Arena players makes the transition to paper, I hope they like what they see enough to stick around.

Modern History

Let’s get to the game itself. Preparing for two Constructed formats at once is a tough challenge requiring careful time management. ‘Luckily,’ one of them was just more of the same.

Stop me if you’ve heard this before: Golgari Food and Izzet Phoenix are the best decks in Historic, but you can play control if you really want to. Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty added a lot to the format but didn’t change the fundamental terms of engagement; Streets of New Capenna didn’t add much, but perhaps did more with it.

Ledger Shredder is an amazing tool for Izzet Phoenix in any format – another discard outlet for Phoenix itself, a threat that doesn’t use the graveyard, and a great way to punish the mirror or other decks playing at a similar rhythm. Phoenix used to have a lot of flexibility in its secondary threats; you knew you wanted Dragon’s Rage Channeler and Arclight Phoenix, but after that you saw everything from Delver of Secrets and Symmetry Sage to Sprite Dragon and Stormwing Entity with a side of Crackling Drake and Brazen Borrower. Which of those you want is still a major point of contention and differentiation between Phoenix lists, but all of these take a back seat to Shredder now.

Creatures (9)

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (23)

Spells (26)

Unlicensed Hearse arrived just in time to keep this menace in check. There’s no shortage of good graveyard hate cards in Historic, but this is the first one that can also become a serious threat without the immediate vulnerability to removal of a Scavenging Ooze or Lion Sash. As a colourless, asymmetric hate card that can be used on demand, even its primary targets have an interest in booking it. Lots of Izzet Phoenix players added it to their own sideboards, and Merkel’s winning Rakdos Arcanist list – another archetype that hates to see a Hearse on the other side – features a full four copies in the maindeck!

People came prepared to beat Phoenix this time and they succeeded. Its overall win rate was poor and not indicative of the ‘best deck’ status it has held for months. I don’t expect the deck to go anywhere, but in future Historic tournaments (if there were even any to care about…), it won’t be an easy default in quite the same way.

And then there’s Golgari Food. This deck dominated the Innistrad Championship, became the prime target at the Neon Dynasty Championship as the Japanese team that put it on the map switched to Azorius Control to beat it, and then returned in full force here. David Inglis and Zachary Kiihne continued their incredible seasons by running back an almost identical Food list to the one their team also used to dominate Historic last time.

Creatures (13)

Lands (23)

Spells (24)

For a brief moment it looked like the deck might become even better by accident. The original Painful Bond, at left above, is a dangerous card to print into a format where Lurrus of the Dream-Den is legal and gave Golgari Food (Lurrus) a way to grind even harder without the setup requirements of Deadly Dispute. Lists with full sets of Bond and Dispute performed well early and it looked like anyone hoping to win in Historic would need good dexterity (and good Internet!) for these Food mirrors.

The even more confusing nerf to Painful Bond took that new element away but left the same shell intact, featuring the same core that has somehow thrived in Historic through all of its alarming upheavals. Cauldron Familiar and Witch’s Oven will continue torturing opponents, viewers, and commentators for as long as they are allowed to – and if those aren’t one of the best strategies in the format, you know something scary is happening.

Control flopped hard this weekend. Even the diehards who play control whenever possible mostly shied away from it, and those brave souls who powered through anyway did poorly. The Japanese squad’s success with Azorius Control (Yorion) last time was highly misleading; they performed poorly in Alchemy to start the tournament and include many of the game’s best active players, so you’d expect them to have a high win rate!

Izzet Phoenix – still a tough matchup for control – was guaranteed to be the most popular deck in the event. Control’s natural prey in Golgari Food vanished last time because the most successful Food players before had switched to control, nullifying the main reason to play control in the first place!

The developments on the fringes weren’t promising for control either.

The biggest surprise from the Neon Dynasty Championship were what you might call the Esper Sentinel aggro decks. Azorius Auras had been a staple of Historic for some time, but Light-Paws, Emperor’s Voice took the deck to another level (and opened up other colour combinations like Mardu Auras, pioneered by newly minted Worlds competitor Julian Wellman). Jean-Emmanuel Depraz claiming a spot in that Top 8 was no surprise, but his deck choice was: his take on Azorius Affinity caught the eyes of many and became a popular choice for the New Capenna Championship.

Creatures (31)

- 4 Thalia, Guardian of Thraben

- 1 Thraben Inspector

- 4 Thalia's Lieutenant

- 1 Dauntless Bodyguard

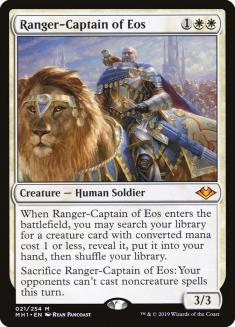

- 4 Ranger-Captain of Eos

- 1 Giant Killer

- 3 Skyclave Apparition

- 4 Esper Sentinel

- 3 Adeline, Resplendent Cathar

- 2 Katilda, Dawnhart Prime

- 4 Inquisitor Captain

Lands (25)

Spells (4)

While my teammates were posting obscene win rates with a months-old Food list, a group of us including Top 8ers Simon Nielsen and Karl Sarap wanted to try something different.

Once you decide Esper Sentinel is appealing against a field of Phoenix and control, you note that these other Esper Sentinel decks are also heavily reliant on noncreature spells, prompting a search for a Sentinel deck that doesn’t share that weakness. If Sentinel is strong in a format, then Thalia, Guardian of Thraben is phenomenal – as long as it isn’t holding you back too! – and Ranger-Captain of Eos lets you triple down on that exploit.

The Selesnya Humans deck that was all the rage in Historic months ago was a natural place to look. Just like Izzet Phoenix at this tournament, the format adjusted to Humans at the Innistrad Championship and kept it in check, but the kind of removal that’s effective against Humans isn’t reliable against the other Sentinel decks or useful against the big three. There was a large, Human-shaped hole in the metagame for our cavalry to charge through. If we could avoid a resurgence of Golgari Food – a matchup that could be fairly described as The Meathook Massacre in the past – we were set.

Some crucial and puzzling changes have also happened since then:

There is a vocal crowd that claims Alchemy has ruined Historic – a bold claim if you look at the results of any real Historic tournament, where the total Alchemy representation rounds to an average of one Cursebound Witch in some Food lists.

The real impact was in the nerfs to top Standard cards for the sake of Alchemy, which carried through to Historic for some reason. This created a weird discontinuity between the formats this time; I could play the printed Luminarch Aspirant in my Standard deck but not in my Historic deck (the best possible home for it!), even though the power level of Historic is much higher. The removal of Aspirant had further consequences for the deck – marginal one-drops lost a lot of their appeal without the follow-up threat of Turn 2 Aspirant – and could have stopped its comeback in its tracks.

Thankfully, Alchemy gives as well as takes. Inquisitor Captain has been through some changes itself, but its current form is an ideal curve-topper for Selesnya Humans, teaming up with Collected Company to let you punch through or reload in the mid-game and allowing consistent access to your important creatures. If, like me, you have nightmares about whiffing completely on a Company, Captain at least guarantees a fine body with a relevant creature type up-front.

That’s just the format that was a (mostly) known quantity. How about a brand-new Standard format?

Setting a Standard

For almost everyone – viewers and players alike – their last glimpse of Standard was of Faceless Haven struggling to outrace Alrund’s Epiphany and Divide by Zero in a narrow, stale format. Since then, those cards have been booted out, two more sets have been added, and the format is refreshingly different.

Well, mostly…

Creatures (7)

Lands (20)

Spells (33)

Jeskai Storm – or ‘Dragonstorm’ if you’re from a certain generation – burst on the scene in Neon Dynasty Standard and caught the eye of anyone paying attention then. In a format defined by slow, midrange slugfests, this classic combo deck existed in its own universe. Our most pressing question for this tournament was whether the new cards would allow other strategies to catch up to this deck or if our time was best spent perfecting Jeskai Storm.

I was stunned to see Big Score in the Streets of New Capenna previews until I learned that the set file was locked in by the time Unexpected Windfall dazzled us all at the last World Championship. The Galvanic Iteration + Unexpected Windfall engine that leveled up Izzet Epiphany and was the centerpiece of Jeskai Storm now had additional redundancy and was guaranteed to survive beyond the imminent-ish rotation of Windfall, staying in Standard until September 2023!

As other previews trickled out and made little impression, there was a good chance the best Constructed card from this multicolour set would be an upgrade to a mono-red uncommon that had already told its punchline.

The breakout card of the Neon Dynasty Championship, Fable of the Mirror-Breaker deserves an audition in any deck that can cast it and is a good reason to branch into red for those that can’t. It seems out of place here – the Goblin token isn’t a useful game piece for the rest of the deck, the rummaging from the second chapter is redundant with your Windfalls, and you don’t have good targets to copy with Reflection of Kiki-Jiki – but in practice the card is much more than the sum of its parts. As a cheap proactive play, it punishes anyone trying to play reactively against you, and it puts you in a position to take a turn off chasing a Big Score to chain into your combo turn.

Though other teams and players chose to battle with Jeskai Storm, the metagame at large didn’t respect the deck and focused their attention elsewhere. ChannelFireball’s Grixis Vampires list, for example, packed a bunch of Annuls for the poorly performing Naya Runes decks, but only a single Disdainful Stroke and Go Blank; flip those numbers around and the matchup suddenly becomes much harder. Even if the format does become more hostile, Jeskai Storm will remain the most fundamentally powerful deck.

Creatures (8)

Lands (22)

Spells (30)

Fable revived another much-hyped archetype – the Jeskai Hinata deck that Jan-Moritz Merkel used to slice through the Top 8 and claim his crown. Once again, the deck doesn’t maximize any individual aspect of Fable, but the total package streamlines a somewhat clunky deck with a lot of moving parts.

The abstract appeal of both of these decks is that they dodge the midrange arms race that has consumed the rest of the format. Esper Midrange was the deck to beat for this weekend, but you could also take your pick of Jund Midrange, Naya Midrange, or Grixis Midrange from these Top 8 decks. On one level, this is a victory for the New Capenna crime families and the set’s gold theme, but it’s easy for these decks to blur together.

Creatures (12)

Planeswalkers (7)

Lands (26)

Spells (15)

Creatures (14)

- 1 Legion Angel

- 2 Skyclave Apparition

- 4 Luminarch Aspirant

- 4 Gala Greeters

- 2 Workshop Warchief

- 1 Sanctuary Warden

Planeswalkers (3)

Lands (22)

Spells (21)

Creatures (14)

- 2 Bloodthirsty Adversary

- 4 Bloodtithe Harvester

- 2 Evelyn, the Covetous

- 4 Corpse Appraiser

- 2 Tenacious Underdog

Planeswalkers (4)

Lands (26)

Spells (16)

Creatures (10)

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (26)

Spells (22)

Esper Midrange is headlined by Raffine, Scheming Seer and dips into its colour pairs for cards like Kaito Shizuki and Vanishing Verse, but these other midrange decks mostly feel like collections of cards that happen to be in their colours – newcomer Hisamichi Yoshigoe’s Naya deck doesn’t have a single Naya or Cabaretti card (or any gold cards at all). The choice between Jund and Naya isn’t between Ziatora’s Envoy over here and Fleetfoot Dancer over there; it’s which of The Wandering Emperor or The Meathook Massacre you want to pair with Fable of the Mirror-Breaker and Esika’s Chariot.

This sense of sameness is encouraged by many of these cards sharing similar play patterns. They create more material turn after turn, giving a cascading advantage to the person on the play and making it increasingly difficult to catch up from behind as these cards all line up well against cheap, targeted removal. What are you meant to do against Fable or Chariot other than play your own – or play a totally different game? Planeswalkers inherently follow this dynamic, but so do all the other marquee threats in this Standard.

This results in a format where winning the die roll feels like a better predictor of your chances in the match than the matchup itself or specific deckbuilding choices. The good games of this Standard are very good, but too many are over before they begin.

The end of this chapter means that there is little reason to focus on these formats anymore and competitive play as a whole enters a lull for a few months. There’s nothing left to do other than congratulate Jan-Moritz Merkel on this exclamation point in an incredibly impressive and consistent performance spanning several years, formats, and platforms.