Hello, and welcome to this edition of Sullivan’s Satchel. The previews for Innistrad: Crimson Vow are coming down the pipeline, which also represents the first set I worked on as an initial designer for Wizards of the Coast (WotC), rather than with Play Design. The latter proved a tricky fit; I found the remote testing resources laborious, and so much of the work is being ambiently involved in conversations that are harder to insert yourself into working from another city.

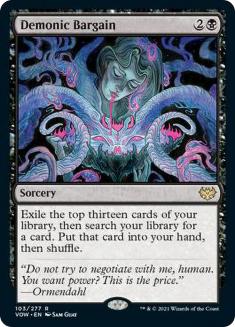

The initial design teams proved a smoother fit. There were meetings, and work to do on my own time, and random design needs to fill, and I consider it to be my best work while I was there. Not coincidentally, it’s cool to see so many designs I pitched in a meeting or design assignment go straight to print, or with slight numbers tweaks. Seeing Demonic Bargain in print is the coolest experience I’ve had related to Magic since leaving the project in June. I still sort of can’t believe it.

With that, the questions. As always, you can send in yours to [email protected] or DM me on Twitter @BasicMountain. I typically answer even the below average, typo-riddled ones, but if you really reach for the stars and send me a banger your question can win Question of the Week™, with $25 in SCG credit sent straight to you.

From JP:

I think there’s a plausible argument that it makes sense to cram a lot (but not all) of the high-quality removal and sweepers into a single color. Some of that is definition; density matters along with quality, and so giving a single color a wide array of plausible options makes it clear that’s a specialty, similar to red typically getting more than one priced-to-move burn spell in a given Standard format.

But also it alleviates pressure. Removal is very strong but typically on diminishing returns; the first pushed sweeper you give a color is likely to be format-defining, the second and additional copies not so much. Loading up black with that much quality removal (individual and sweepers) allows those cards to compete with one another, and they are more likely to rotate in and out of decks depending on metagame peculiarities. If you spread out the cards in the question among all five colors, it’s very likely that that’s the sum of the Standard experience, or close to it.

As far as challenges go: making sure that not every problem is easy to solve, or that other colors answer certain problems much more efficiently; making sure that each piece of removal or sweeper has pros and cons compared to other options; and making sure that the game isn’t unreasonably biased towards destructive interaction in a general sense. I think Standard has shown good balance in this specific respect for the last few years.

From Andy Hurst:

My question is: How does this line up with the general desires of Design folks like yourself? Do you find it more fun to iterate and innovate on proven and popular ground, or do you often prefer the blank canvas of a new place with new flavor and new mechanics, even though there’s the greater risk that what you’re attempting might not gel with the audience or measure up to what’s already been done?

Thanks for your time!

I imagine there are some marketing incentives at play that you alluded to. It’s much easier to go back to places that are popular for reasons that go outside of design. However, I don’t think I’d characterize it as “derivative” versus “blank slate” in each case. For example, what are the defining features of Ravnica block? I guess one could say that they are the initial mechanics like dredge or haunt, but for me it’s much more about the underlying architecture. Here are ten color combinations, and a broad set of expectations; now go to work.

Much the same is true of Innistrad — creature types centered around the allied color combinations, cards that transform, and stuff that cares about the graveyard. Again, some things to center the design, but by no means prescriptive. But that architecture doesn’t preclude doing things that are very innovative or exploratory. Disturb is that sort of thing in my opinion, and it could appear in Innistrad or in some other block as well. I think it’s fair to say that Amonkhet was “new” from a world building perspective, but wasn’t taking big risks in terms of the mechanics that appeared. Sometimes the easiest way to find something new is to piggyback on stuff that’s old.

I’m a big believer in the proof is in the pudding, combined with novelty has value for its own sake, up to a point. In other words, some mechanics or creative conceits might only have a set or two in them, and some might have an endless number of blocks to piece out of them, over time. I like working in both spaces some amount more than working in either exclusively. I’m generally happier working with stuff that I believe in and where the conversations are more easily anchored around agreed-upon targets, so if I had to choose between one or the other, I’d go with the remixes.

From Andrew Brown, sort of:

I think there are a lot of ways to approach Andrew’s question, and the most obvious is “do you like this as a player,” which my answer doesn’t really speak to. If you like Wall of Omens for whatever reason, that’s cool. It isn’t an offensive design by any means, even if I think it’s a bad bet for balancing Standard metagames.

I’ve talked a lot about trying to balance around all possible outcomes, that you can’t just analyze what happened after the fact, with all the information, and assume that if you repeated the experiment a million times you’d get a million identical results. It’s through this lens that I think Wall of Omens is remembered more favorably in Standard than what would happen if it got printed a bunch of times.

Its debut came at a time when white was particularly underpowered and in a format that was weirdly balanced around a bunch of busted cards that dealt three damage (Lightning Bolt, Bloodbraid Elf, and Sprouting Thrinax, to name a few). In that world, Wall of Omens served to prop up a color that wasn’t strong, subsidized a play pattern that wasn’t present, and served as a backstop against a few cards that were a bit too ubiquitous and powerful. So far, so good.

Most Standard formats aren’t balanced around precisely those cards, and in the average world I think it makes Standard worse, on average, and sometimes much worse. The card itself isn’t especially interesting to consider as a deck choice or on the battlefield, so whatever card someone would play instead is almost certainly more stimulating to consider. And there are significant taxes on incentives, as I mentioned in my initial response — game length, potential invalidation of a plethora of appealing cards, planeswalkers too challenging to manage through combat, and so on.

My argument isn’t that Wall of Omens is out of bounds on rate, or would be a disaster every time. I just consider it a bad bet. There are ways to get the “good” parts a lot more reliably with designs that are more interesting and have much less downside risk.

Lastly, the Question of the Week™, and winner of $25 in SCG credit, from Markus Leben:

What things should a designer do to avoid overcorrecting? What made these game pieces bad bets? And what do you look for in a card meant to fight against problem cards in an environment?

To me, the sin isn’t “overcorrection” per se. Some cards or strategies represent a major risk on rate or play pattern and Appeal to Moderation Bias has sunk more balance calls than going too hard, in my experience. The biggest issue that I see is leaning too heavily one one card. For one, that card is likely to come with a ton of rate to make sure it solves the problem. Unsurprisingly, a lot of the cards you called out as “solutions” went on to become “problems” down the line.

Secondly, it isn’t that satisfying. Yes, beating the bully with a new tool can be fun and satisfying. But for how long? And how much agency did you feel when you did it? Thragtusk, I think, is an example of doing it the right way; here’s some stuff that’s appealing and doesn’t seem particularly engineered, but it happens to be the thing you want against Delver without coming with a Red Elemental Blast or Plummet attached.

I think my preferred approach is to take a bunch of small stabs at the problem rather than one big one, and be willing to avail yourself of bannings if that approach doesn’t pan out. Who cares if Teferi, Time Traveler wins out against Wilderness Reclamation or not over the long haul? Both are pretty terrible things to balance a format around, in my opinion.

So start by placing the bets in stuff you believe in, and then to whatever extent you want to seed in countermeasures, make sure those are bets you believe in independent of the fallout with whatever you see the problematic cards or decks as. Sometimes circumstances are extraordinary and it’s important to acknowledge that as part of the range and act accordingly, but often this stuff sorts itself out in satisfying ways by moving the needle here and there.