Hello, and welcome to this week’s edition of Sullivan’s Satchel. The big news from last week is the announcement from Wizards of the Coast (WotC), shuttering the MPL and Rivals at some point in 2022 with no digital analog to replace that level and form of Organized Play. In its place, a return to a focus on paper play, the details of which are still to be determined, but with the declaration that being a professional Magic player (as in, to subsist off tournament winnings) won’t be a goal or even a possibility under this new system. With so many specifics still unknown, it’s hard to know what to make of everything, but even absent that it seems clear that the MPL, and Magic’s foray into esports, was mostly a failure.

This doesn’t come as a surprise to me. Magic has always punched below its weight from a coverage perspective. The complexity and opacity of the rules set is such that novice players can’t make sense of what’s going on just from watching (compare to Hearthstone, to say nothing of something like League of Legends). Even people familiar with the game in a general sense often don’t have the level of intimacy with a specific format to follow what’s happening, or appreciate the tactical nuance inside of a game or matchup.

And Magic has enough variance that creating a steady cast of characters at the top requires massive efforts to keep them there. This froze nearly every player from aspiring to reach Organized Play’s highest ranks. If an Organized Play system doesn’t create a particularly good experience for the viewer or excitement for invested players to get there themselves, it’s unlikely to stand the test of time, and so here we are.

Again, with so much unknown, it’s hard to know where to go “from here,” though plenty of people were pessimistic about the future of competitive play. I’d be patient. If you asked me to optimize an Organized Play system that focused on local paper support but gave people something to aspire towards, I am positive I could create something better than the pre-MPL Organized Play even with fewer resources. The SCG Tour has been instructive for me, as has my own arc as a competitive player. Most players, even extremely competitive ones, don’t necessarily aspire to play Magic for a living. Give them regular tournaments with stakes, and the occasional big event to qualify for, and that’s more than sufficient. The architecture required to make Magic a career just isn’t worth the squeeze, in my opinion. I guess I’m on the optimistic side of this, all told.

With that, the questions. As always, you can submit yours to [email protected] or DM on Twitter @BasicMountain. They get answered if they’re reasonable and not redundant, and then one gets selected as Question of the Week, with the person submitting that question receiving $25 in SCG credit to boot.

From Friend of the Satchel™ Ben Seitzman:

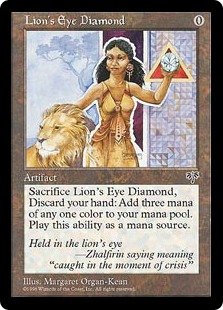

“Rate” broadly speaks to how powerful something is in absolute terms, combining a blend of “specific context” and “an aggregation of all contexts that could reasonably exist.” That’s not a simple thing to define. How much “rate” does Lion’s Eye Diamond have? It would have no purpose in the average Standard format, but in larger formats becomes one of the most powerful, defining cards. How about Questing Beast, which cuts the opposite way? I think it’s fair to say both cards have a lot of rate; they’re far more powerful than the vast majority of all Magic cards ever printed. But there isn’t a firm definition and the details can make it murky.

When looking at powerful cards, I try to ask two questions. First, “How much game happened leading up to the moment of casting?” Second, “How much game happens in its aftermath, and how satisfying is that game to play?” Lion’s Eye Diamond, when it is powerful, plainly fails both tests as hard as possible. It’s all about facilitating fast combo kills with minimal interaction points. Now, I think it’s fine to say that it adds texture to older formats and part of the experience there is supposed to be the gloves coming off, but anything like Legacy Storm would be wildly inappropriate for Standard play.

It’s also why it’s typically good to put a lot of rate into planeswalkers. There’s a lot of game leading up to it (they typically cost four or more mana), the game leading up to it is dynamic and satisfying (the particulars of the battlefield inform how strong the planeswalker is), and when they’re strong there’s naturally a lot of game going on after the fact, since they’re value engines that need to be extracted over time.

It’s also why Oko, Thief of Crowns is so egregious. It comes out too quickly, and the aftermath of it renders all opposing draw steps moot. Teferi, Time Raveler fails these tests in slightly less extreme ways. It comes out quickly, but the real problem is the caster gets most (if not all) of their money back the turn they cast it; anything that happens after that is just gravy. Less dynamic, less burden on its caster to play a two-player game to make it powerful.

This question is tricky in part because there are a lot of ways to mess up a card, but the short version is — something cheap and powerful should make the subsequent turns interesting to play, and something expensive and powerful should care about what happened leading up to the moment where the card got played. Many of Magic’s most powerful designs fail both tests, but a handful (Bloodbraid Elf; Gideon, Ally of Zendikar; and Settle the Wreckage immediately come to mind) pass both and are in my opinion good bets to make among the most powerful cards in a Standard format.

From Anderson LeClair:

If you want to get into the nitty-gritty, this rules doc is still up and accurate, to the best of my knowledge:

As far as the testing and strategy goes, the big thing is what color combinations you want to put in Seat A (most protected picks in Packs 1 and 3) and Seat C (most protected picks in Pack 2.) For example, in Odyssey/Torment/Judgment black was very obviously the best color in Pack 2, and so the Level 1 strategy is putting black in the C seat, with white (strong in both Odyssey and Judgment) in the A seat.

But this doesn’t answer the entire question. What is your second color in both? What metagames well against the obvious color distribution? Which color do you “split?” Remember, three two-color decks is six total colors, so your team has to double-dip at least one color. This requires a ton of repetition, and ironing out edge cases. For example, our team once spent six practice drafts simulating that we kicked off and opened Shadowmage Infiltrator as the rare, a card that was powerful and very awkward for our preferred color distribution. My vague recollection of our strategy for that format was R/W in Seat A, G/U in Seat B (with some flexibility), and G/B in Seat C, and no team we played at the PT did the exact same thing.

I can’t imagine spending a second of my life testing something like this again, but for where I was as a competitive Magic player, it was a real treat.

From Kevin Bell:

I leave that to Cedric’s steady hand, both because he has a better sense for such things than I do and also because he has taken several of my concepts and turned them into Coalesce Merchandise shirts without compensation (sending me t-shirts in the mail doesn’t count, before you offer that up). (CEDitor’s Note: It counts.) I’m not even sure what something like that would look like. I’m also not worrying about it. Boss man can figure that one out.

From Ranveer S:

Depends on what your budget and preferences are. If you have limited resources and/or really like playing one style of deck even if it isn’t very good, that answers the question. If you’re looking for more generalized “investment” advice, just buy the powerful lands. Fetches, Ravnica duals, fastlands, whatever. They’re powerful, they’re desirable in Commander and so stable even in the face of reprintings, and some blend of them is a prerequisite to build most powerful decks. The creatures and spells come and go, but the lands have looked more or less the same for a long period of time, and I don’t expect that to change anytime soon.

Lastly, the Question of the Week, and winner of $25 in SCG credit, from Mike Stein:

I think the big thing was getting an appreciation for the zero-sum nature of winning, and how games have to fight tooth and nail against that reality. It sounds simple, but it’s a tremendous burden. Only one person wins, and if the game is only fun when you’re winning, that’s the death knell. I think it necessitates mechanics that make someone achieve mini-goals or other sorts of “unlocking” moments. Level up, battalion, delirium, and several others allow a player to feel like they completed a quest or turned their cards into something greater than the sum of its parts, even if they ultimately go on to lose the game and match.

When someone signs up for a match of Magic (tournament setting or otherwise) there’s an understanding that they might lose the match, but that’s very different from getting humiliated, or their cards not working, or never having a moment where they put the other player into some sort of tough spot. Judging tournaments and selling singles really drove home the reality that some ways of losing are more fun than others and the game should aspire to optimize the experience for the losing player as much as possible.

As far as player archetypes, the “Star of the Show” was something that occurred to me while working at TOGIT. It isn’t analogous to one-on-one play, but comes up in multiplayer settings, which are now probably the primary way Magic is played in person. In short, some people don’t really aspire to win (or don’t think they can), but still want one moment where the spotlight is on them and they’re creating the dramatic moment, or dictating the terms of engagement, if only briefly.

Lots of ways this can inform design, but big, dramatic moments where the casting player has a fair bit of agency in how it plays out but is getting the “worse end” of it on rate (by something obfuscated, by allowing other players to “go first” with their decisions or cards, etc.) can allow certain players to get their moment in the sun and allow all the other players at the table to win more often, which increases everyone’s fun over time.