I said it in this week’s Zendikar Rising Standard What We’d Play and I’ll say it again:

What started as a seemingly innocuous tweet from Bryan Gottlieb ended with Ondřej Stráský absolutely crushing the CFB Pro Showdown with the following list:

Creatures (25)

- 4 Gilded Goose

- 4 Wicked Wolf

- 2 Charming Prince

- 1 Kogla, the Titan Ape

- 4 Yorion, Sky Nomad

- 4 Llanowar Visionary

- 4 Skyclave Apparition

- 2 Tangled Florahedron

Lands (18)

Spells (17)

In the time since, most of the talk around the Magic community has been around Yorion and how to beat Yorion. For a lot of folks this involves actually playing with Yorion and being favored in the mirrors, but what does that actually mean?

What Yorion Is Doing

The first step of knowing how to be successful in a Yorion fight is knowing what exactly that entails. This isn’t to outline every flavor of Yorion, though Gottlieb did a fantastic job of that in his article this week, but to actually examine the axis that these decks are trying to operate on.

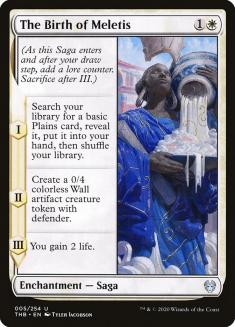

At their core, Yorion decks are looking to snowball an advantage with a pile of battlefield advantages. This is generally going to look like permanents that have some sort of spell attached to them when they enter the battlefield. We’ve seen a lot of these before — Elspeth Conquers Death, The Birth of Meletis, and so on — but the decks themselves are leaning a bit more into the synergy of simply playing cards that grow their battlefield material.

Focusing a bit more on the Selesnya Blink flavor of Yorion, it’s incredibly synergy-rooted, specifically in the Food angle provided through Trail of Crumbs, Gilded Goose, and Wicked Wolf. What’s worthy of note is that all of these cards contribute to growing the deck’s proverbial snowball bigger. It’s kinda similar to the video game Katamari Damacy.

For anyone who hasn’t had the privilege of playing the game, the short version is that the main character has a ball of objects that can pick up any smaller object that it touches in order to grow their ball bigger. That means that as the ball grows, the objects it can pick up grow as well.

Selesnya Blink isn’t entirely dissimilar, in that the more pieces the deck has access to on the battlefield, the more powerful its Yorions are going to be. In the same vein, the more Trail of Crumbs there are on the battlefield, the more a player is going to benefit from sacrificing a single Food, and so on.

Part of what makes this possible in both instances is that in the Katamari world, and at the time of Selesnya Blink’s inception, nobody is competing on that axis. All that needs to happen is the deck needs to secure the means to keep growing its ball and presumably it will run anything it plays against out of resources.

Similar to the systems Katamari is used to criticize, this sounds great in theory but runs into problems in practice. If everything in the deck is committed to simply growing one’s own ball, the mirrors are going to be hard to break through and battlefields are going to end up impossibly clogged.

Whenever engaging on the same axis as these decks, there are three ways to comfortably come out ahead: building towards a specific breaker, suppressing their game, or including tools that can completely subvert the axis the game is being played on.

Breakers

“Breakers” is a shorthand term for a way to break through a battlefield stall. These kinds of cards were absolutely crucial during Eldritch Moon Standard because of how cluttered the battlefield would become in a Bant Company mirror.

Creatures (26)

- 1 Jace, Vryn's Prodigy

- 4 Reflector Mage

- 4 Sylvan Advocate

- 2 Archangel Avacyn

- 3 Tireless Tracker

- 4 Duskwatch Recruiter

- 4 Spell Queller

- 4 Selfless Spirit

Lands (16)

Spells (18)

Though Archangel Avacyn ended up being the breaker of choice, Subjugator Angel saw a bit of play as the best way to crunch through a battlefield of any size. The details change from format to format, but what’s important here is noting that there was a way to literally end a game.

There are a few things that can be used to invalidate all of the battlefield advantages that have been gained by an opponent, including a pet favorite of mine:

Creatures (12)

Planeswalkers (1)

Lands (22)

Spells (45)

For the most part, this deck looks like a straightforward take on last format’s Orzhov Doom Foretold decks, with one major splash:

One of the best ways to punish players for putting all of their eggs in a single basket is to blow up the basket. This isn’t always going to be the the kind of thing that’s worth putting a bunch of reactive seven-drops in your deck for, but with a deck that lacks a meaningful way to apply pressure in the way that Selesnya Blink does, it’s a nice reset.

The other tool in the deck that acts as a breaker is a bit less one-sided, but more familiar:

Including Ugin, the Spirit Dragon takes a few levels to arrive at.

- Ugin is a great card and I obviously want to play it in any deck looking to go long.

- Ugin is awkward because my deck is also trying to snowball a battlefield advantage.

- Ugin is good because I am in control of the parts of the battlefield it interacts with.

Level 3 is the primary level that communicates why Ugin is strong in these mirrors, despite looking like something that would unilaterally wreck the battlefield before getting tagged by Elspeth Conquers Death.

The biggest things that Ugin is great at gobbling up are Trail of Crumbs and leftover copies of Omen of the Sea against blue Yorion concoctions. It also is Wheel Of Fortune-plus-Eureka if left alone for a couple of turns, but that’s a little Magical Christmas Land-y.

This deck is also a prime example of how to suppress the opponent’s game.

Suppression

Suppressing the opponent’s gameplan involves disrupting what they’re doing. In synergy decks, that can mean trying to attack the enablers or the payoffs in order to give them all gas and no match, or vice versa. It can also look like playing cards that line up favorably against specific kinds of cards for the sake of making it harder for the opponent to play the game they want to play.

During its time in Standard, Narset, Parter of Veils was largely used as a suppression tool against Hydroid Krasis and the Explosion half of Expansion. She was also strong against the go-long decks that wanted to play X-spells because she was also a Divination in a grindy matchup.

Doom Foretold decks are built to operate on a similar axis in the face of a million different permanent types.

So Carmen, what you’re saying is that removal is good against permanents? Real 9000 IQ stuff you’ve got going on here.

Doom Foretold is at its best whenever games are going to be going a long time, and the most important thing a player can do is have a ton of permanents on the battlefield. It’s the kind of card that can create an artificial ceiling on how much value both players Yorions can get. It also makes it hard to actually snowball any kind of advantage that requires the same few permanents remain on the battlefield for multiple turns.

Doom Foretold specifically is different from something like Gemrazer because it’s repeatable and ends up combatting a long-game strategy’s ability to play to the long-game. Reducing the efficacy of a deck’s cards is a way to fight on its own axis without losing to their deck’s primary game plan. It doesn’t always need to be something as heavy-handed as Doom Foretold, however.

Carmen, I swear if you tell me that using counterspells as removal…

Okay, but, to borrow a line from the late Billy Mays: “Wait, there’s more.”

Negate, and other counterspells, represent a favorable mana exchange against an opponent that gets better as the game goes on. Trading two mana and Negate for five mana and Elspeth Conquers Death, for example, is an incredibly favorable tempo exchange. For decks that are looking to win on the back of mana advantages, this is an enormous deal.

One of the nice things that counterspells can do as well is maintain a battlefield advantage. A tactic that Yorion decks with more interactive forms of value are going to make great use of:

Creatures (24)

- 4 Solemn Simulacrum

- 4 Charming Prince

- 2 Thassa, Deep-Dwelling

- 2 Dream Trawler

- 3 Yorion, Sky Nomad

- 3 Barrin, Tolarian Archmage

- 4 Skyclave Apparition

- 2 Glasspool Mimic

Lands (30)

Spells (26)

On top of Thassa, Deep-Dwelling repeatedly paying its controller in a way that’s similar to Doom Foretold, Barrin, Tolarian Archmage has the benefit of pushing his controller closer to ahead on the battlefield when he resolves. Both players stuck in a holding pattern is going to inevitably favor the player with more value already on the battlefield, and this type of deck plays to that.

The card Mystical Dispute in particular is one that has the benefit of helping force through certain threats by interacting with the counterspells that other players are bringing to the table. It still manages to find its way into decks like these because it can also play reactively against the clunkier value-engine pieces like Elspeth Conquers Death and Ugin.

Paulo’s list also includes a threat that’s a great example of the third point: subverting the expected axis of gameplay.

Subversion

Whenever two players play a game of Magic against one another, each deck is trying to fight a specific battle, or operate in a way that utilizes a certain strategy. This is frequently referred to as a gameplan, but the chunk of Magic that it uses to implement said gameplan is the axis that the deck is trying to fight on.

Yorion decks, for example, are largely trying to play to the battlefield, and generate resources in the form of tokens or interaction with permanents that do something when they enter the battlefield. A lot of Standard decks end up operating on the battlefield, but the specifics of the cards they’re using to play with or the kinds of cards they’re comfortable interacting with change.

Creatures (25)

- 4 Gilded Goose

- 4 Wicked Wolf

- 2 Charming Prince

- 1 Kogla, the Titan Ape

- 4 Yorion, Sky Nomad

- 4 Llanowar Visionary

- 4 Skyclave Apparition

- 2 Tangled Florahedron

Lands (18)

Spells (17)

Look again at Ondrej’s Selesnya Blink list from last weekend. Most of what this deck is trying to do is use spot removal to answer problematic permanents and clog up the ground with creature tokens. There’s a great threat that happens to get around all of that:

Despite playing to the battlefield in a way that would instinctually do exactly what Selesnya Blink wants, Dream Trawler is something that Selesnya is going to struggle to lay a finger on. It’s for this reason that players have started to lean much more into making a Dream Trawler happen and then protecting the queen, Dragonlord Ojutai-style:

Creatures (4)

Planeswalkers (2)

Lands (33)

Spells (41)

- 2 Negate

- 2 Essence Scatter

- 2 Mystical Dispute

- 4 Glass Casket

- 4 Omen of the Sea

- 4 The Birth of Meletis

- 4 Omen of the Sun

- 4 Elspeth Conquers Death

- 4 Shark Typhoon

- 4 Mazemind Tome

- 4 Transmogrify

- 3 Valakut Awakening

Sideboard

On top of having a pile of Negates that play to the point being covered before, a smattering of Dream Trawlers ensures that this deck can beat the brakes off the traditional Selesnya Blink deck, because it’s doing things that Selesnya Blink can’t reliably interact with. That includes using effects like Transmogrify to cheat out early copies of Dream Trawler, due to Selesnya Blink being incredibly light on instant-speed removal.

Playing on a different axis is going to be one of the more difficult ways to actually fight while still maintaining the guise of playing a similar archetype. The first two methods are far more common than subversion, but Depraz’s take on Jeskai really drives home how much emphasizing a single card can be the mirror-breaker in what would otherwise be a pseudo-mirror.

Zendikar Rising Standard at this point is hardly solved, but understanding how to fight mirrors is one of the most important things one can do in 2020, when most Standard formats devolve to a single boogeyman or two ravaging everything else. Being successful in those later stages of the format is contingent upon learning which of these advantages will be the best to play to on any given week.