This was going to be a very different article until I woke up on Monday morning.

Once you read about Lurrus of the Dream-Den being banned in Modern, how can you write about anything else?!

Despite following Oko, Thief of Crowns and Uro, Titan of Nature’s Wrath in back-to-back sets, the companion mechanic is still the most glaring example of the issues with that era of Magic design. Lurrus of the Dream-Den racked up some unique and dubious accolades. It’s the only card to be literally banned in Vintage on power level for a quarter of a century. Now it’s the only card that received functional errata in Modern and had to be banned anyway. The original Lurrus was in contention for best creature of all time, and even the nerfed Lurrus wasn’t far down that list.

The sweeping round of bans last February removed those other mistakes from the last relevant Constructed formats, but the companions stuck around. For almost two years now, from Standard and Pioneer through Historic and Modern, you fully expected your opponent to reveal a companion and felt behind by default if you couldn’t do the same. Some formats were remarkably light on companions recently, but this problem was at its worst in Modern, whose top tier has been a battle between Lurrus and Yorion, Sky Nomad for months now.

It’s not hard to build a case for axing Lurrus, but let’s look at the case that was actually made.

Lurrus’s play rate (31% in Magic Online League decks that started with four wins) points to a card that is contributing to the homogenization of the Modern play experience. There is not a significant enough deck-building cost to incorporate it into a wide variety of strategies.

The ‘play rate’ statistic (also used in the Pioneer section) stands out for both its novelty and its strange boundaries. It includes decks that go 5-0 by definition and also decks that 4-0 but lose the final round of a League, but excludes a deck that picks up a loss early and then finishes the League 4-1, even though (based on the little public information there is about League matchmaking) those results aren’t much less useful for the sake of this discussion.

I expect this new metric stems from a desire to cite something quantifiable without the issues that arose from the raw win rate statistic. Announcing that Dimir Inverter had a 49% win rate in Pioneer Leagues to justify their inaction at the time made it tough to explain why the Inverter ban was necessary later. As Patrick Sullivan notes, the scale of the difference between a 52% win rate and a 54% win rate isn’t inherently obvious, at least without a thorough explanation that would remove the need for that statistic in the first place.

This description also dodges the central issue of how and why Lurrus is so ubiquitous. In every format, some cards are the most popular or powerful, and these set the terms of engagement for everything else. The first half of the explanation could just as easily apply to Lightning Bolt as to Lurrus. Ultimately, these cards still have to be placed in decks at the expense of other cards and still have to be drawn (or found with some effort) to appear in games. Even if their play patterns are repetitive, the rules of deck construction and the game itself place a cap on how often these cards can appear.

By design, the companion mechanic flouts this fundamental aspect of the game engine. Even if every Lurrus deck were a Lightning Bolt deck, Lurrus would be a factor in every game in a way Lightning Bolt never could be. Lurrus’s power makes this more obvious and obnoxious – the Kaheera, the Orphanguard that Azorius Control gets on the house doesn’t provoke these complaints – but no companion can avoid it entirely.

This should increase the pressure on a companion to add variety to gameplay when it inevitably arrives. Lurrus does just the opposite, replaying the same cards that have appeared in the game already and allowing you to build around the threat of looping the same card ad nauseam. If you had to design a card with “homogenization of the Modern play experience” as an explicit goal, you couldn’t do better than Lurrus.

There isn’t some new printing or new context that made Lurrus a problem in this way. All this was obvious on Day 1. The logic of the announcement applied to Lurrus at every point in the past two years. So why did it take two years to properly neuter it?

The next part of the announcement does look different today:

The point about mana curves becoming compressed as a format increases in size is important and has applied to Lurrus throughout its existence. For a format that now includes almost twenty years of cards, this is inevitable in a way that ties into the format’s charm; maybe you could tell in 2006 that Mishra’s Bauble would eventually cause problems, but nobody predicted this!

This framing of the incentives around Lurrus raises a larger question about Modern Horizons 2, which did more to apply this pressure than any other set. If this occurs organically with regular sets over time, why not tack hard in the other direction and push cards higher up the curve that offer unique deckbuilding incentives of their own?

The biggest trade-offs prompted by Lurrus in the last few months were technicalities; yes, your Murktide Regent costs two mana in practice most of the time, but these numbers in the corner mean that you have to make a choice now. I guess I’m glad you couldn’t play Lurrus and Solitude in the same deck, but I wish that conflict was more intuitive and less contrived.

As with many previous ban announcements, I’m happy with the outcome, but the reasoning only leaves me with more questions. Letting the original companions out the door is such an egregious mistake that I’d want a future banning announcement to engage more with the bigger picture.

How About Pioneer?

The Pioneer section offers more food for thought:

Finding a role for Standard cards as they rotate out was an explicit goal of Modern at its inception. Pioneer had to pick up that torch once Modern became too large to do that properly. That goal takes a step back in a world where paper Standard is mostly extinct and the digital platform where the vast majority of Standard play occurs has Historic to fill that gap but no longer plans to support Pioneer.

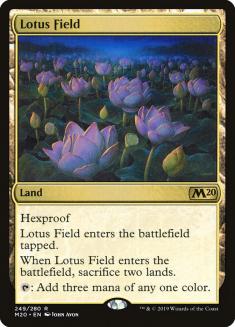

The more abstract goal of having various forms of Standard inform Pioneer can be tough to meet consistently. Some decks carry over very nicely – if you played Boros Feather in Core Set 2020 Standard, you have most of a top-tier Pioneer deck (that can now even consider playing Feather again!) – but these are few and far between. Other strategies have a clear analogue in Pioneer with some of the same flagship cards; if you loved playing control with Teferi, Hero of Dominaria in Standard, you can keep doing that with a new supporting cast. In the other direction, a format like Pioneer has a level of tolerance for strategies that are out of bounds for Standard. You couldn’t build Lotus Field Combo in any Standard format, and it would be a big oversight if you could.

The unfortunate reality is that the cards most likely to make the leap are the ones that proved too good for Standard – often in a highly obnoxious way. The lasting consequence of the War of the Spark through Ikoria run of sets was that the same new cards took over every Constructed format. If you wanted to escape Uro, you could do that everywhere; if you wanted to escape from Uro, your options were… Pauper or Vintage?!

For the most part, Pioneer has been the sweet spot for these cards to coexist with healthy competition. Fires of Invention with Lukka, Coppercoat Outcast was hopelessly broken in Standard but (at least with the companion tax) has behaved well in Pioneer. Putting Cauldron Familiar into Witch’s Oven here yields a range of healthy dishes that people aren’t too sick of yet.

One could argue that Pioneer – and therefore Lurrus – had already reached the point of no return where Lurrus was a free and extravagant gift for the decks that adopted it. Azorius Ensoul (Lurrus), Boros Heroic (Lurrus), and various Rakdos decks all picked up Lurrus at minimal or no cost. That said, I appreciate the awareness that this will only be more and more true in the future and the willingness to act later rather than even later.

What’s Next For Modern?

The Lurrus decks lost an incredible, guaranteed extra card; the other decks did not. Picking the winners and losers there is easy, right?

The fact that Lurrus was so free for so many decks hides that it was much more important for some than for others. Every deck that played Lurrus is still viable – part of why this ban was such a clear call for me is that it doesn’t invalidate anyone’s investment in the format or shake it up too drastically – but will have to process this loss in its own way. There are decks with Lurrus, and then there are Lurrus decks.

Some of Modern’s classic linear decks treated their free Lurrus the way you might treat a pizza coupon in your mailbox. You should have played Lurrus in Boros Burn, but there was so much debate about it precisely because it barely mattered. If you played Dimir Mill, you could forget to reveal your companion and probably not be punished for it.

If Lurrus had one redeeming feature, it was as a perfect illustration of the differences between Burn and Prowess in Modern. Lurrus was essential for Boros or Rakdos Prowess, as they rely on their creatures as their primary damage source; these draw out removal, making it more likely that Lurrus survives and helps you rebuild. Boros Prowess saw a small resurgence in the last few weeks, but its future is more uncertain now.

Lurrus let the Colossus Hammer decks put the same squeeze on the opponent. If they didn’t have removal for Puresteel Paladin or an equipped creature, they would often die on the spot; if they did, you could present the same threat again with more protection in a turn or two. For a deck whose main plan is somewhat susceptible to interaction, Lurrus joined Urza’s Saga as a valuable way to fight back there.

Creatures (20)

Lands (23)

Spells (17)

Despite this, CrusherBotBG dominated the Modern Challenges on Magic Online (MTG) with a Lurrus-less build of Hammer using more expensive Equipment like Nettlecyst and Sword of War and Peace to turn any creature into a serious threat in the fair games without needing Sigarda’s Aid or Puresteel Paladin. For most of this time, they were the only player doing this; now, this approach is the only game in town.

This contrast highlights how stifling Lurrus had become. This new build presents Hammer players with more deckbuilding decisions, and the bigger Equipment enables a wider range of games. Hammer is now a more interesting deck from both sides. You have to pick your spots more carefully, as you can’t rely on getting your enabler back eventually, and you can point your Fatal Push at a creature without sighing at the inevitability of Lurrus undoing your hard work. Anyone who had picked up Hammer as their Modern deck of choice gets to stick with it but has some interesting puzzles to solve now.

Lurrus has always had a complicated relationship with the premium interaction in Modern. The companion mechanic and the specific play patterns of Lurrus and Yorion were fatal for anyone trying to exchange resources and play a ‘small’ game – you would rather bring so much interaction that you could fight the companion-induced second wave too, or ignore this fight and pursue a more proactive plan. At the same time, Lurrus fit perfectly into the black midrange decks as both a threat (that could buy back other threats) and a source of extra cards to press your advantage in this low-resource game.

I doubt Bloodbraid Elf is back on the menu with Lurrus gone. Lurrus not only effectively soft-banned some cards, it showed that those decks were probably better off without them anyway. There is more room for three-drops specifically as Ragavan can accelerate into them on Turn 2, but the bar is still high here.

The best deck in the format last week was a deck in this space that relied on Lurrus and must now adapt to survive:

Death’s Shadow often felt like an afterthought in the deck named for it. Unlike the original, threat-light builds of Grixis Death’s Shadow, today’s lists get to play Dragon’s Rage Channeler and Ragavan. Part of this shift in focus came from Lurrus kicking out Street Wraith, placing a cap on how quickly you could cast and grow Death’s Shadow. Now that Wraith is on the table again, Shadow itself becomes more appealing, as do former Grixis staples like Temur Battle Rage that relied on Shadow. Without Lurrus’s late-game firepower, being able to take this more aggressive stance is valuable.

Wraith makes it easier to suddenly achieve delirium for Dragon’s Rage Channeler and Unholy Heat – creature was a hard card type to place in the graveyard on demand – or change the size of Death’s Shadow out of nowhere, leading to more dynamic games. The Lurrus chess match in the mirror had its own charm, but I think this version of Grixis Death’s Shadow will also be more interesting to play with and against.

Izzet Midrange isn’t affected directly by the loss of Lurrus, but its competitors in the same space are. If you were debating between Izzet and Grixis, access to Lurrus was a compelling tiebreaker.

That choice is made for you now, but that doesn’t lock you into Izzet. Why not have the best of both worlds?

Thoughtseize and Inquisition of Kozilek are the perfect pairing for Murktide Regent as cheap sorceries that clear the way for your Dragon while letting you cast it early. This package never had a good home before, but with Lurrus gone, I expect to see a lot of decks built around this core – new versions of Grixis Death’s Shadow as well as more generic Grixis Midrange.

The combo decks in Modern will be praying that Grixis struggles to find a new form. Amulet’s comeback tour a few months ago was abruptly canceled by the emergence of Grixis Death’s Shadow. Izzet Murktide still poses a big problem for Primeval Titan but is a much easier foe than Grixis was for Gruul Charbelcher.

The elephant in the room here is Yorion, now the undisputed best companion in Modern. Four-Color Control used to boast a good matchup against the other top-tier decks in Orzhov Hammer (Lurrus) and Grixis Death’s Shadow (Lurrus), but Grixis had figured out how to flip that matchup in its favour and linear decks like Boros Burn and Gruul Charbelcher forced Four-Color Control to cover too many bases at once.

Now Hammer and Grixis are scrambling to find their footing again and the printing of Boseiju, Who Endures lets Four-Colour Control hedge against fringe strategies while threatening a lock with Wrenn and Six. I would expect to see a lot of larger decks in the next few weeks, and that shell isn’t going away any time soon.

The nightmare scenario here is that action has to be taken against Yorion too. On top of the inherent issues with companions, it brings its own form of repetition that mimics Lurrus by reusing existing game pieces instead of adding anything new. Rather than finding inventive ways to use those extra slots, the proven approach is to pad your deck with cards like Abundant Growth and the redundant copies of important effects that you can find in such a large card pool.

I’m not sure what the end-game is here. Do we eventually cut our losses with the mechanic entirely and try to move on? If Yorion has to go too, will Modern tournaments in two years or five years still be punctuated by the occasional quirk of someone revealing a free Jegantha or Kaheera that they barely care about?

This announcement was an opportunity to do more, but I’m glad they finally did something, and I’m keen to see where the format settles after this latest shock.