I have been playing some alternative formats on MTGO recently, and I have noted how strongly the limitations of the format — specifically the limitations on the allowable mana — define the metagame. It isn’t just the broken spells that make Vintage what it is — it is also the available manabase. It would be hard to demonstrate that (Vintage with no non-basic lands?), but I can show just how dramatic the impact is in another format. That format is an oddity, but the results have implications for other formats as well.

The oddity format is Rainbow Stairwell Highlander. RSH is highly structured. Each player plays a set number of basic lands, a set number of non-basics, and six cards of each color, plus artifacts. Those six cards must have converted mana costs of one through six. Split cards, X spells, and multicolored cards are all banned.

I played this format a lot back in 2005. I started playing it a lot again recently. I did notice two big changes. First, the manabase standard that people play has changed, becoming more restrictive. Second, the metagame has slowed significantly, and has become much more controlling. I was wondering if these were related. After working on the format a while, I concluded that a more awkward manabase was creating more color screw, which had the effect of slowing down the format significantly.

Back in 2005, we played fewer basic lands and had more colored mana available, faster. Mid-range beatdown was common, and control had to play much more removal. Today, people are requiring more basics, games are generally longer and slower, and slots that used to be dedicated to removal or land cyclers are being used for Control Magic effects and planeswalkers. I have built a speed deck that can beat the current control decks, but it relies on a ton of Morphs to do so — yet more evidence of the impact of the manabase.

My hypothesis was that color screw was slowing down the format, but testing that directly would require building lots of decks, then playing a ton of matchups. However, if it is true, the reason the format is slower must be because color screw is preventing people from playing better/color intensive cards, at least for a couple turns here and there.

That is a testable hypothesis, which means we can look at some data and see whether it is correct, or whether I am just babbling.

To test it, I can take a reasonably standard control Rainbow Stairwell build, then play a bunch of goldfish games with each different mana base and count the number of times cards are stuck in my hand because I did not have the appropriate color to cast them. (Note — I need to track color screw, not mana screw. Since the format defines the number of lands I can play, only color really varies.)

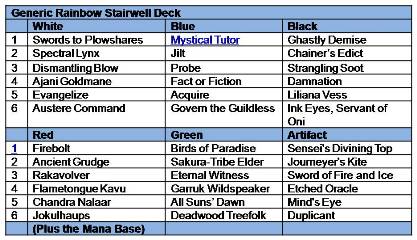

Here’s a pretty decent/generic control build.

The next step is to choose the manabases to be used in the test. I found three worth testing.

Original Manabase

One of the first references to Rainbow Stairwell I can find is in a Dec, 2003 article by Abe Sargent. Abe notes that the rules on lands have varied, and that groups tend to agree on house rules for the format. Here’s a snippet:

For lands, you have twenty spots. You can choose the lands ahead of time, so your group could, say, require use of a specific set of lands (such as four (City of Brass) and two of each dual land.) Or you can allow the player to use whatever land they own that’s legal. Maybe you’ll want to restrict non-basics to playing a single copy of each, just like your spells. I would recommend that only lands that tap for colored mana (and that’s it) be allowed if you permit players to choose their lands. That way, you avoid Wastelands, Volrath’s Stronghold, and other such lands from being used.

The 2005 Manabase

Bennie Smith wrote about Rainbow Stairwell in his Into the AEther column on the flagship site back in April of 2005. At that time, the recommended manabase was three of each basic land, plus two copies each of the Invasion taplands. In other words — this:

Land:

3 of each basic land

2 Elfhame Palace

2 Shivan Oasis

2 Urborg Volcano

2 Coastal Tower

2 Salt Marsh

The Current Manabase Options

In the Rainbow Stairwell Revival Thread in the Wizard forums, the above manabase was called Rainbow Stairwell Pauper, and Mana 211 said that, for Rainbow Stairwell Singleton, your manabase can be either 3 or 4 of each basic, plus a complete cycle of non-basics plus four additional non-basics. (Examples of cycles include Odyssey block Filterlands: Darkwater Catacombs, Mossfire Valley, Shadowblood Ridge, Skycloud Expanse, Sungrass Prairie; or Onslaught block Fetchlands: Bloodstained Mire, Flooded Strand, Polluted Delta, Windswept Heath, Wooded Foothills.)

Most recently, the people I have seen playing a lot of Rainbow Stairwell had agreed on the second choice for a manabase: four of each basic land, plus four non-basics of your choice. That is the manabase that I have been playing recently.

Let’s test them in reverse order — the current default manabase first, the optional cycle plus four second, then the twenty dual lands build.

The Nuts and Bolts

I decided to play ten goldfish games with each deck, and play out eight turns per game. Since I would be on the draw, eight turns would give me 15 cards, meaning that I should, given a 24 land build, have six lands on turn 8. I decided to mulligan anything below a two land plus mana fixer hand, but not to mulligan based on speed or color mix, otherwise the test would be too subjective.

I recorded a “card-turn” every time I had a card in hand that I could not cast due to color screw. I defined color screw as being unable to cast the card with all relevant kickers and so forth. For example, if I started turn 3 with a Plains and a Salt Marsh on the table, my hand consisted of Probe, Rakavolver, Sakura-Tribe Elder, Plains and Firebolt and I drew a Forest, I would list one unplayable card: Firebolt. (I never want to play Rakavolver without at least one, and preferably both, kickers, so I don’t count it as unplayable on turn 3.) I also didn’t count a card as uncastable just because I played a different land. For example, if I had a City of Brass and a Thawing Glaciers, plus Firebolt and Swords to Plowshares in hand turn 1, I counted everything as playable even if I played the Thawing Glaciers. (Had my opponent presented a threat, I would have played the CoB, instead.)

I counted each time that a card was stuck in hand due to color for a turn as a “card-turn.” This meant, if I had Garruk in hand from turn 1 but never found a second Green source until turn 1, Garruk would count as a stuck card turn for turns 4, 5, 6, and 7 — or four “card turns.” I did not count turns 1 through 3, since Garruk is a four-drop.

“Card-turns” is, in effect, a measure of how badly and for how long you are color screwed. Note that it only counts only color-screw: since all decks run 24 lands and the same mana fixers, only color is relevant. I did not count Garruk as a color screw if a deck was stuck on two Forests and a Plains on turn 6.

Remember, the hypothesis is that more basics means more color-screw, leading to a slower format. That’s all I was testing.

I tested on MTGO. This meant I did not have to worry about how thoroughly I was shuffling, since the shuffler gave me a good randomization instantly (important when doing a lot of goldfishing.) On the downside, using MTGO in solitaire mode meant that I could not pop Thawing Glaciers during my opponent’s turn, so I occasionally ended up discarding things because the Glaciers was the eighth card in my hand. It was rarely relevant. I usually discarded cheap, castable removal, since I probably would have cast that in a real game.

One other problem — early in the test, I drew Sword of Fire and Ice, but had turned off the pre-combat stop. This meant I did not draw an extra card that turn, but I don’t think that mattered. On the flip side, Mind’s Eye is bugged in Solitaire mode, since you can basically draw one card per mana, but I did not abuse that.

Overall, I don’t think testing in solitaire mode on MTGO affected the results in any significant way — other than shaving off an hour of shuffling time.

The Results

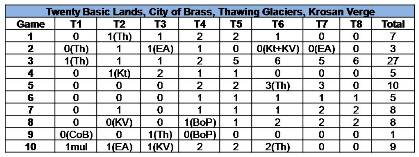

Twenty Basics

This manabase uses four of each basic land, plus four non-basics of your choice. Decks pretty much universally use Thawing Glaciers as the first land fetcher — I see it everywhere. The next two slots typically include City of Brass and Krosan Verge. The final slot varies, and I have seen everything from Grand Coliseum to Sunhome, Fortress of the Legion. I played Academy Ruins, a common choice which I run in most of my control builds.

This is by far the most restrictive mana build, and it showed. Over the course of the ten 8 turn games, I often faced color screw. Here’s an example of the sort of things I would see.

That was a particularly bad game, even though I opened with a turn 1 Thawing Glaciers and thawed like crazy all game. I had one uncastable card (Firebolt) turn 1. Over the course of the game, I was color screwed for a whopping 27 card-turns. It was the worst game, but color-screw was common with this build. On average, the twenty basic land manabase meant that slightly over one card was uncastable due to color screw every turn.

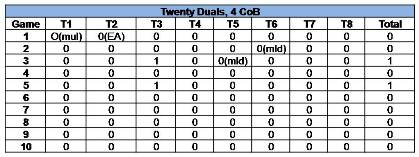

Here’s the raw data.

Let me define the notes. (Th) means played Thawing Glaciers for the first time. (Kt) is Journeyer’s Kite. (KV) is Krosan Verge. (EA) means that I Forestcycled Elvish Aberration. (CoB) means that the land played was City of Brass. (BoP) is Birds of Paradise, of course. (Mul) means I mulliganed.

This manabase slows the game down roughly one whole turn over a more color-friendly manabase. That is significant — actually, that is a ton.

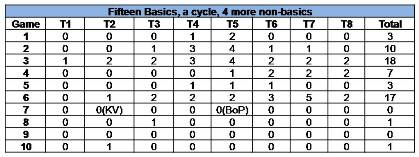

Fifteen Basics:

The manabase I used to play was 15 basic lands (three of each), plus a five-card cycle or lands, plus another four basic lands of your choice. I was feeling nostalgic, so I chose the Invasion taplands (Coastal Tower, etc.) as my cycle, plus the same four non-basics used above.

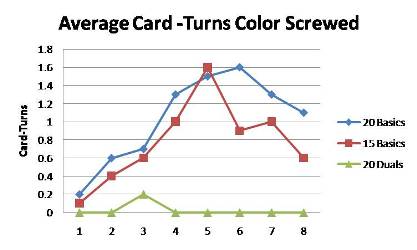

This build shows that color screw still happens, but it is less likely. That is about what you would expect, because the build adds one more mana source per color. Like the four basic land build, cards are most likely being stuck in hand on turns 4 and 5 — which is to be expected since the deck has a lot of double-colored-mana cards in those slots. This build has slightly more problems on turn five than the 20 Basics build, but that is probably because of the comes-into-play tapped lands. I should probably redo the test with duals instead of Invasion lands, but I have already spent too many hours on this.

Overall, this build has an average of slightly under one card stuck per turn, compared to slightly over one for the 20 lands build.

Twenty Dual Lands:

For a final build, I decided to go with Abe’s 20 dual lands, 4 City of Brass build. I could have improved consistency even more with fetchlands, but this seemed the best of the actually—played manabases.

I adjusted the maindeck slightly: Sakura-Tribe Elder and Journeyer’s Kite make no sense in a deck with no non-basic lands. Sakura Tribe Elders became Farseek, and the Kite became Umezawa’s Jitte. True, Jitte does not fetch lands, but I figured it didn’t matter. I was right — this deck is nearly immune to color screw. Here’s a typical example of the deck in play.

I cast Probe on turn 3 (no kicker), then basically quit. This game the deck will have access to two of every color mana from here on. That was typical. Even when I mulliganed, I almost never had problems. I think the data showed that I could not cast a card exactly twice — and one of those was when I could not cast an Eternal Witness on turn 3. I counted that, despite having nothing in the graveyard.

Let’s graph the results.

I started wondering about these manabases, and whether the choice makes much difference. It’s pretty clear they do. The more color sources, the fewer cards sit, uncastable, in your hand.

I’m sure that the manabase issues have affected the Rainbow Stairwell format significantly. I think that the four basics rule has slowed down the format, and that is the main reason that the slow control decks are dominating. If the manabase were better / less basic, then the more aggressive and mid-range decks would have a better chance of competing. Since these decks would be dropping threats more rapidly, they could beat up on Planeswalkers, thereby limiting their effectiveness. If the format were faster, decks would play more creatures, meaning Evangelize might not be as deadly as it is today.

Whatever. Rainbow Stairwell is a fringe format, and I doubt many people care much about it. However, the lessons learned in RS apply to every format.

My hypothesis was that the lack of access to decent mana slowed the Rainbow Stairwell format. Let me rephrase / reverse that hypothesis — access to multi-colored mana can speed up a format. That is, in effect, a corollary; but think about it: having more multi-colored mana sources available means that you can play more cards, in more colors, faster. Access to reliable enough mana is what makes multi-colored decks possible. Multicolored decks mean you can play more good cards, and develop more synergy.

For example, look at what past formats have had available, and what we have available now.

Back in the days when Standard was Urza’s Block and Mercadian Masques, the multicolored land options were basically Thran Quarry, the five Ice Age painlands and City of Brass. Sabre Bargain was a potent combo deck built around broken card drawing (Urza’s Bargain), but it was not that fast. Its mana messed it up a bit, despite having Dark Ritual and Grim Monolith, because colors were a pain.

Compare that to the current Standard, which features all ten painlands, the Future Sight duals, the Coldsnap taplands, Shimmering Grotto, Gemstone Mine, Gemstone Caverns, Vivid lands, Terramorphic Expanse, Coldsteel Heart, Prismatic Lens, Coalition Relic, Lotus Bloom — and on and on. We get a new cycle of dual lands in Shadowmoor, and I have not even touched on the dozen or so Green mana fixers.

Standard is going to be fast, even if great cards are not printed, simply because the mana works.

On Monday, Patrick Chapin wrote about a RWGbu deck that relies on cards with casting costs of RRR, GW, 2UW, 2{U/W}{U/W}{U/W}, 1UWB and more — and his deck includes four Swamps that come into play tapped. A 5 color deck like that would barely be possible in some past Extended formats, much less Standard, but it works now. It works because, when it comes to colored mana sources, we have an abundance beyond anything in the past.

I like colorful.

PRJ

“one million words” on MTGO