Once upon a time, speculating on Standard rares was a nice way to make money.

It was simple: I’d watch the Pro Tour, read articles from the best deckbuilders, and pay attention to what made Top 8 at the Star City Standard Opens. Then I’d buy copies of every rare under $3-$4 in the newest, most exciting lists. It was hard to go wrong when a single event could turn a bulk rare into an $8-$10 staple. I could even make good money by nailing a sleeper rare or two during the pre-order period and watching it take off.

This doesn’t happen much anymore.

Very few Theros Block cards were worth speculating on at any point this year. There were exceptions, sure, but they were few and far between. If you had pre-ordered your Temples of Malady at $5, you would have been pretty happy. Eidolon of Blossoms was a little undervalued at $2. Courser of Kruphix was the big winner out of Born of the Gods, and two of the three Temples in that set rose as well. Hero’s Downfall went from $5 to $15 and back to $5 again, and Thassa and Master of Waves doubled in price for about a weekend. Before that, you have to go all the way back to Mutavault, Lifebane Zombie, and Scavenging Ooze last summer to find a reasonable spec.

So what happened here? Was Theros underpowered? Were the good cards all too obvious? Was Standard too stagnant and predictable?

All of those things are true to some degree, but there’s something bigger going on as well. The game has changed, and if you want your specs to make any money, you need to understand the new face of Magic.

The Saturation Point

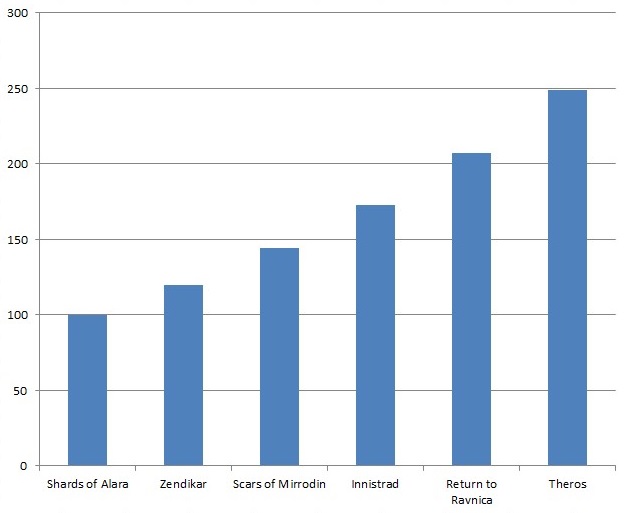

I talked a little in last week’s mailbag article about Magic’s unprecedented growth. According to Hasbro’s investor conference presentations, the game has grown by roughly 20% per year each year since 2008. Looking at a number that big is one thing, but seeing it in action is another. Here is what 20% growth looks like in bar chart form, starting with 2008’s Shards of Alara block at a neutral score of 100:

This is 20% year-over-year growth visualized for six straight blocks. Assuming print runs are increasing at the same pace as the growth of the player base, there are two and a half Theros rares out there for every Shards of Alara rare.

But that growth shouldn’t be affecting card prices, right? After all, we’re measuring the growth of the player base as a whole, which should mean an increase in demand roughly equal to the increase of supply. If everything is increasing, then surely a rise in the player base along can’t account for a change to the Magic economy, can it?

That line of logic is more-or-less true when it comes to the staples that everyone wants, which explains why cards like Thoughtseize and Courser of Kuphrix are still worth as much as they are, even accounting for increased print runs. Here’s an analogy to explain:

Pretend there is a small group of Magic players. Four of them play Standard and are always after the latest and greatest cards, and six of them only play Commander and kitchen table formats. Each player buys a box of Worldwake and has a 50% chance of opening a Stoneforge Mystic. Five Stoneforge Mystics are opened, and the four competitive players in the group manage to trade for all five between them.

Now let’s assume that the group doubles in size. There are twenty players, twelve casual and eight competitive. They each open a box of Theros, and ten of them open a Thoughtseize. The eight competitive players manage to trade for all ten between them. In this case, both the supply and demand have increased in tandem, causing the price of staples to stay fairly uniform over the years.

Now let’s examine a card like Mana Bloom that isn’t a universal staple. Our small playgroup analogy no longer works because demand for Mana Bloom is much softer than one in ten players. For the sake of this exercise, let’s say that two thousand people worldwide have decided to build a Mana Bloom deck and to everyone else it’s a bulk rare. That means that only eight thousand copies of the card are needed, and all the other copies are simply going to sit around in trade binders and bulk boxes. At this point, the only way that a card can rise in value is for the demand to increase faster than the rate at which new copies of the card are entering the marketplace plus all of the available copies that are sitting around find a buyer!

Market saturation like this happens very fast on Magic Online. Because it is so easy to match buyers with sellers, cards with soft demand can end up tanking to the point where they’re only worth a few cents each. In paper Magic, matching each card to its eventual buyer is a little harder. Reaching the saturation point can weeks, even months.

But how does increased supply affect the saturation point of a card when demand is still rising in tandem? Let’s use two low-demand rares – one from 2008 and one from 2014 – as an example. The figures I’m using here are fictitious because I don’t have anything approaching print run numbers to use as an estimate. The ratios, however, are based on the 20% year-over-year growth we established earlier.

2008 Rare

4,000 copies needed

40,000 copies opened

2014 Rare

10,000 copies needed

100,000 copies opened

If this were a simple math problem, nothing would change between 2008 and 2014 because supply and demand are both increasing at the same rate. It’s not a simple math problem, though – it’s an economics problem. And economically, the difference in supply between 40,000 and 100,000 cards is much different than the increase in demand between 4,000 and 10,000 cards.

First off, there’s a difference between the overall number of cards in the world and the overall number of cards available in the marketplace. When a card first appears on a Pro Tour stream, players flock to the usual sources to get their copies – local stores, trading partners, and online websites. With an additional 80,000 copies in circulation, it is less likely that this initial rush will cause every vendor to sell out, something that usually spikes the price across the board. This effect is magnified locally, where you might be the only person at your store building a given deck. It’s easier to trade for four copies of something when there are fifty possible trading partners than if there were just twenty.

Increased supply also makes it harder for a store, speculator, or group of investors to affect the market. It’s no secret that some people out there try to spike the price of older cards, buying everyone out and causing the price to shoot sky high. These days, the supply of new cards is large enough to make Standard market manipulation nearly impossible. Even the speculation butterfly effect – thousands of different weekend speculators each buying an additional playset or two as an investment – makes little to no impact on the market for newer cards. Standard Magic is just too big.

Market saturation is also impacted by efficiency. Magic Online, as I mentioned earlier, is much more efficient than paper Magic because everyone is essentially in the same room as everyone else. There are no shipping fees or transaction delays. There is no downtime between buying a card and getting it in the mail, or between opening it in a draft and listing it for sale. If Magic Online’s secondary market hadn’t been designed by a drunk octopus – how is it that we don’t have fractions of a ticket yet?!? – card prices would rise and fall even quicker.

In addition to the increased print run issues we discussed above, the market for paper Magic cards has become much more efficient over the past few years as well. The major stores like Star City Games have been more aggressive with their pricing, improved their shipping costs, and have done a better job keeping Standard staples in stock at all times. The online trading community has seen a renaissance, with sites popping up that have eliminated the risk of sending your cards to a scammer. Other sites have consolidated and democratized the card dealing process, allowing everyone to sell their cards to consumers at current retail prices while linking together all the smaller storefronts. So not only is it easier than ever to buy and sell cards, but the overall ratio of printed cards that are available for sale or trade at any one time has increased massively.

This last point, more than anything, is what has turned the short term spec flip into a much harder play than it used to be. Take Amulet of Vigor coming out of Pro Tour: Born of the Gods. Early in the day, Matthias Hunt’s latest brew looked like the big winner. It was crushing all comers and looking like a world-beater on the stream. When word trickled down to me that the deck was performing well, the card was on sale at Star City for $1.50. Two hours later, it was $5. By lunchtime, they were out of stock everywhere at $10. Everyone who wanted a set for Modern was scrambling for them, as were loads of people in the speculation community.

A few years ago, it would have taken days for a significant number of Amulets to show up for sale after the initial surge of speculators. During that time, people who bought in early would have had a nice window to try and sell their copies in the $6-$10 range. That did not happen this time around. As the day progressed and Hunt’s deck was proven to be fairly expensive, tricky to play, and possibly not the format-warper we had thought, demand for the card softened. Dozens of copies were listed by people who dug through their bulk in the hopes of making a profit, and the race back to the bottom begun. There wasn’t enough real demand to satisfy the price spike, so the card dropped back down below $5 the very next day. There are loads of them in stock for $4 each right now.

Enterprising day traders can still take advantage of spikes like this, swinging deals when demand is at its highest, but for the rest of us, speculating on a card that turns out to be a dud is much riskier than it used to be. You might not have lost money on Amulet of Vigor, but you probably didn’t make much on it either. And that card didn’t even come from a recent set – Worldwake was massively under-printed compared with everything that has been released since!

What about casual cards, then? Should we start focusing our attention on Commander playables instead of the latest Standard goodies? In order to answer that question, we’re going to need to attempt to figure out the solution to a very interesting riddle: What percentage of Magic players are casual as opposed to competitive?

Our first problem this is a very subjective line of inquiry. Can you tell me where the line between casual and competitive should be drawn based on the following player profiles?

Player #1: Bought a fat pack once. Plays with the contents from time to time.

Player #2: Has a couple of decks built. Plays at school and summer camp sometimes.

Player #3: Buys a box every time a new set comes out. Uses the contents only for casual decks. Has never heard of Commander.

Player #4: Plays weekly, but only with a friend’s Commander decks. Doesn’t even have a DCI number.

Player #5: Brings a burn deck to FNM once a month. Usually loses.

Player #6: Plays Standard every few weeks with a modified event deck. Has never played in a PTQ.

Player #7: Drafts weekly at FNM. Owns no constructed cards.

Player #8: Plays Standard every week with a rogue deck. Went to a GP that one time.

Player #9: Tries to keep up with the winning decks, but has no interest in the PT grind.

Player #10: PTQ grinder.

We can probably all agree that player #1 is casual and player #10 is a competitive player, but there is still a rather large gray area in the middle. Are you a competitive player the minute you enter a tournament, regardless of how good your deck is? Are you a competitive player once you start seeking out Standard staples, even if you’re going to use them for Commander? What if your Commander is Arcum Dagsson and you play cutthroat Commander to get the win? What if you draft all the time and generally do well but own no cards at all?

Unfortunately, we don’t have enough data to even explore a place to draw that line. When attempting to measure the number of competitive Magic players in the world, I only came across a single useful data point: a forums post from a judge in 2011 stating that there were 417,000 active players in the global DCI database. This number included every tournament grinder in the world at the time, but it also counts every ‘casually competitive’ man and woman whose only sanctioned events include prereleases. For this exercise, I’m going to shave 20% from that figure to represent the number of players with an active DCI number who could not be called competitive in any way, shape, or form. That number is pure guesswork, of course, but it won’t be the most egregious misuse of math we’re going to be exploring today.

At any rate, if you take 20% off the top and then add 20% growth year-over-year until 2014, you end up with about 576,500 competitive Magic players today. Correct or not, that’s the estimate I’ll be using going forward.

Of course, this number isn’t very useful if we don’t know how many players there are overall. Hasbro is even stingier about this kind of information, so we’re going to have to extrapolate an answer based on even more guesswork and even rougher estimation.

According to this press release from May of 2009, Wizards of the Coast estimates that there are twelve million Magic: the Gathering “players and fans” worldwide. What does it mean to be a ‘player or fan’ of Magic? I have no idea. Are they counting lapsed players from the early 1990s who could somehow still be considered ‘fans’ of the game? What about a kid who played three games on his kitchen table with his sister last Christmas after getting a duel deck in his stocking? Press releases like this are supposed to be boastful, so whomever crafted that twelve million figure probably had a lot of creative license to try and make that number sound as large and impressive as possible.

For our purposes, then, I’m going to cut that number in half and guess that there were about six million people in May 2009 who would have considered themselves to be Magic players. Is that number too high? Too low? I’m not sure, but I’d wager it’s far closer to the true figure than WotC’s estimated twelve million.

Now let’s update that six million player figure for modern times by using our 20% year-over-year growth figure. In May of 2010, the number goes up to 7.2 million. By May of 2011, it’s 8.64 million. By May of 2012, we’re at 10.39 million. By May of 2013, 12.44 million. By May of this year, we’re at a whopping 14.9 million active Magic players. That’s huge!

So what percentage of Magic players are competitive? According to this back-of-the-envelope calculation, a little less than four percent.

This four percent figure is a good reminder of why WotC operates in the manner that they do. Splashy mythic dragons, Duels of the Planeswalkers, the New World Order, and more are done to improve the game’s experience for the vast majority of people who play Magic. Luckily for those of us on the competitive side, most of these changes are good for the game at large. Just remember that you – yes, you – are not in WotC’s main demographic.

Of course, this four percent figure is essentially worthless when it comes to talking about Magic finance. Even if only four percent of Magic players are competitive, that number doesn’t give market share any weight. It doesn’t care if you’ve played one game of Magic or ten thousand. Patrick Chapin’s voice is counted with equal weight to that of Jethro Scrubbs, a kid who only has one deck and every card in it is a basic Mountain.

Before writing this, I asked a bunch of people to give me their best guess for the number of competitive players vs. casual players. The guesses varied wildly, but they clustered around 20%. Without WotC’s internal data, I have no way of knowing what percentage of product sales go to tournament players as opposed to casual customers, but this figure feels like a good estimate once buying power is factored into the equation. Unless our guesswork is way off, then, this is a casual player’s world and we’re all just living in it.

So why is tournament playability still the biggest driver of card prices? Part of it is that the cards that are good in tournaments are simply the most powerful cards in a given set, making demand close to universal. Another part of it is that many casual players are adverse to buying singles – at least expensive ones – preferring to open packs and building with what they get. Even the Commander playgroup at your local store is on the competitive end of casual – most casual players, the unknown masses, simply buy a pack or two at a time and have a very small collection.

What does all of this mean for the future of speculation? Here’s how I’m changing my approach:

- Whenever a new set comes out, I will be focusing most of my attention on multi-archetype staples. Anything that can only fit in one deck isn’t worth speculating on unless it starts out incredibly cheap.

- I will continue to advocate buying each block’s dual lands as soon as possible, especially if the lands are brand new and not reprints. These are always needed in multiple decks, so they will always be in demand.

- I will not buy any breakout tournament cards unless I know I can flip them immediately or I believe that the demand for them will last long enough for me to make a profit.

- I now believe that single-deck role-players aren’t worth my investment unless I believe that deck will dominate for an extended period of time.

- Any tournament card that is also a casual all-star is always worth a second and possibly a third look, especially if it has applications across multiple decks in multiple formats.

- I will continue to sell high on Standard rares whenever possible, especially those with narrow applications. I will instead focus on acquiring older cards where I don’t believe a reprint is likely.

- When looking for a casual spec, I will pause and remember how large print runs are these days. When speculating on a card that has been released in the past five years, I will consider versatility over playability and focus as much as I can on mythic rares, where the print run numbers are much lower.

- I will no longer advocate buying ‘penny stocks’ like Luminate Primordial, Thespian’s Stage, and Steam Augury until the August before set rotation. Too many copies of these cards have been printed, and it may take years after the set leaves print before demand tips back past the saturation point.

Magic speculation is not dead – far from it – but the game continues to evolve in strange and unexpected ways. Unless you’re aware of the changing patterns in supply and demand, you’re going to find yourself burning through your extra cash without making a dime in return.

This Week’s Trends

- Star City Games has added Modern 5k events to their Sunday open schedule alongside their larger Legacy events. I’ve seen some people overreact and call this the death of Legacy, but I doubt that attendance for those tournaments will be down much. The Legacy player base is hearty and vibrant. They’ll keep turning out. What this will do is increase the overall Sunday attendance for these opens while giving more people more opportunities to play Modern. I wouldn’t sell out of Legacy right now, but anyone who doubts that Modern is the future of mainstream eternal play is kidding themselves.

- Power Nine prices on MTGO bottomed out the day after the set release before significantly rebounding this week. I still expect these to drop again over the next few weeks, though I can’t begrudge anyone for wanting to snag their set now.

- I still expect paper Vintage prices to increase a little as more people get hooked on the format online. Expect power to keep rising along with Vintage-only staples like Time Vault, Bazaar of Baghdad, and Mishra’s Workshop.

- If you’re interested in where Standard is at right now, make sure you read Chapin’s piece from last week. He talks a lot about the different black-based midrange decks that are still dominating the format and the aggressive red and Sligh decks that are gaining prominence as effective hate. Financially, Hero’s Downfall and Thoughtseize are still pillars of the format and good buys. I’m not sure if any rares will see play in enough of the red decks to warrant a buy, but I’m watching Eidolon of the Great Revel closely. If it starts showing up in multiple builds or even in Modern, it could jump in a hurry.

- The prices for Conspiracy singles continue to fall a little, but they’re close to bottoming out. If you want to grab a set of Stifles, now is a reasonable time. The foils continue to rise (if you can find them in stock anywhere!) and are must-buys if you want them long term. Conspiracy boxes have fallen to just $100 retail here at Star City Games, and are a fantastic buy at that price.

- We’re starting our summer lull, and low-end Theros block cards are very cheap right now, along with everything from Commander 2013. If you’re looking to pick any of this stuff up, now is a great time to do it.

- I will be on vacation for the next seven days, so I won’t be as responsive in the comments or on Twitter (@ChasAndres) as I usually am. Don’t worry, though: The Modern Series returns next week, and the Monday after that I’ll be back to talk M15 spoilers and whatever other goings-on have affected the Magic community in my absence.