Magic champions emerge from tournaments, earning fame and glory. I’ve been into Magic for twelve years now, and over the years I’ve observed many different kinds of player. In fact, Magic scenes all over the world look eerily similar.

You’ll meet that guy who’s been playing for ages, but had never won a tournament. You’ll see this kid, youngest in the room, beating everyone he plays… it’s the same wherever you go. Most surprisingly, if you leave a place and return some three or four years later, you’ll discover that nothing has changed: the same guy who’s played Magic forever still can’t win a game, and that kid (who has grown up) still kicks the crap out of everyone.

Why will some players always be better than others? Haven’t you noticed, in your local tournaments, that always the same players always do well, and the same players always fare badly? Even though they spend the same amount of time playing?

I will try to analyze my observations in this article. I realize that it could bring some controversy, but that’s for you to decide.

How would you evaluate a Magic player? What are the different skills a good Magic player must have? The answer comes almost naturally:

-“Pre-game” skills: Deckbuilding, Drafting, Sealed Deck building.

– Play level.

This raises some questions:

Can a good Magic player be a bad deckbuilder?

Can a good Magic player actually be a bad player in terms of playskill?

Pre-game skill is one thing. A successful Magic player will need deckbuilding skills, but he can be helped by his team or get his decks from somewhere else. The one who will earn the most fame and glory, in the end, is the one who will pilot the deck.

While you can be a bad deckbuilder, in order to be a good Magic player you need to play well. You need to play the games properly. Even with good decks, if you can’t pilot them… maybe the odds will be on your side, but you still won’t win on the long run.

When you read articles online, it seems that picking the right deck to take to a tournament, or drafting the right cards, is the most important test. Your result in a tournament will depend on three factors: preparation, playing skills, and luck. You can’t do much about luck, and your preparation will vary from one tournament to another… while your playing skills are the only constant you’ll bring along. They’re what will make you win.

Magic has been around for years, but one thing is striking me. The global level hasn’t improved that much. There’s always been a very limited number of very talented players, which seems to be the same every year in the long history of Magic’s Pro Tour. I remember ten years ago. The Internet Magic scene was little more than a rumor, something only a few could reach. Deckbuilding was something everyone did at home, without relying on the universal test-group on the World Wide Web.

Check the decks from ten years ago – for example, the decks from Pro Tour New York ‘95 Top 8. I don’t think I’m taking too much of a risk in saying that most of the decks were awfully built. Anyone who reads articles on the Internet, or practices deckbuilding themselves, would be able to improve every single of those decks. While you can say that all other decks in the tournament were bad, what helped their pilots win – and become the first Magic superstars – were their playing skills.

Now everyone has access to Magic’s library of knowledge. But are the plays at tournament tables improved through this? I don’t think so.

Just like any other sports, Magic needs some prerequisites. In a way, it’s very similar to any other sport or activity. Take two guys, middle aged, same physical build. Train them at tennis for the same amount of time, separate from each other. Give them the same training, word for word and stroke for stroke.

In the end, will they have the same play level?

Probably not.

How long would it take for the weaker player to catch up? In fact, can he ever catch up?

Taking Magic playskill — we can set up a scale of relative strength, from one to ten, where “one” is a negligible amount of playskill, and “ten” is the optimum amount of playskill. We can classify players by placing them on this scale as befits their ability.

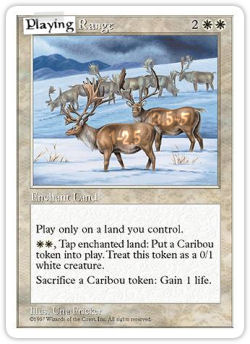

Instead of affixing a single value to a player, each player has a “playing range”. Each player has a playing skill-level that encompasses a certain range of values; he can never play much worse than his lowest point on the scale, but – more importantly — he’ll never play much better than his highest point.

For reference, someone is considered a “player” as soon as he knows the cards and the rules.

The range depends slightly on the player’s age. A very young player will have better chances to improve his game than an older player. In fact, age doesn’t really matter in terms of skills. Julien Nujiten won Worlds ’04 when he was fifteen years old. He’s probably improved his game a bit since then, but he was already the player he is now in 2004.

Every player needs training, just like in every sport. In intellectual sports, you need to train your brain as much as possible. I don’t believe training ten hours a day will make you a much better player… but at least some hours of playing are necessary. You need to understand the format you’re playing, in order to optimize your plays. You’ll reach your highest playing level if you train your brains and are prepared for a tournament.

As I said, it’s not perfect science here. It’s just the comments of my observations. It’s up to you to determine how large a player’s range can be. To me, it seems that the range of a player should be between one and two segments on the scale.

This is an example on how to classify a player:

A Very Bad Player: 1 to 2.5

He is a player who’ll make a lot of mistakes, and will never question his plays after a game. Even though everyone tells him he plays horribly, he simply answers that he plays for fun alone. Even though he plays anything from five to twenty hours each week, he will never improve his game.

No matter what he does, no matter how hard he trains, no matter how much he reads on the Internet… he’ll always be terrible.

A Bad Player: 2.5 to 3.5

He will make fewer mistakes than a Very Bad Player, but won’t know what he did wrong without help. He will ask around about his mistakes, but he’ll make the same mistakes again. He won’t try too hard to improve his game. He will blame bad draws and bad luck. He can’t accept that Magic actually requires skill.

In the end, you’ll never see him at the Pro Tour… or maybe just the once, because luck was on his side on the day of a Pro Tour Qualifier.

An Okay Player: 3.5 to 5

He will make fewer mistakes than a Bad Player. Sometimes he questions his plays, but will need assistance to determine what he should have done. He’s the one you never really know about – he sometimes shows good plays, making everyone believe he’s actually good. In the long run, he will make too many mistakes to be a consistent player.

You’ll see him once in a while on a Pro Tour… but not too often.

A Good Player: 5 to 7

He’s the player ruling the local tournaments. He will question his plays at the end of a game, and find out what he did wrong, to hopefully avoid making the same mistakes again.

He knows how to play. He learns from his mistakes, which makes his ranges larger. You’ll see him on the Pro Tour.

A Very Good Player: 7 to 9.5

He is a player who will question all of his plays after the game. He’ll find out instantly what he did wrong, or what he could have done better.

This is a regular Pro player. While the playing skills vary from one to another, he definitely learns from his mistakes and knows where he went wrong.

An Excellent Player: 9.5 to 10

He just doesn’t make mistakes. End of story.

I don’t think many have reached that level. In fact, I don’t think any active Pro player has this level. Jon Finkel and Kai Budde are probably the only ones to have ever played this highly. Nowadays, this level is more a myth than anything else.

…

Jon Finkel used to say:

“There is only one right play. There’s no such thing as ‘a good play’.”

How can a player find this “right play”…?

I haven’t talked about experience or bluff – or luck – because it’s not purely related to play level. When I talk about prerequisites, it’s about a part in your brain that will make you play better, think faster. It’s a very specific part. Just like some people can do math by simply snapping their fingers, and others just can’t do math at all. It doesn’t mean that if you play bad Magic, you’re not a smart person. It’s just that your brain isn’t optimized for certain types of calculations. Truth be known, it’s difficult to quantify. I really can’t tell what it is. It’s probably called “talent”, but it’s hard to describe.

About eight years ago, I used to know a math teacher. I was studying math back then, and I was amazed by how fast he could solve my problems. He was definitely very intelligent. He also played Magic. A lot of Magic. Maybe five times as much as I did.

In my life, I’ve never seen someone as bad as he was. I couldn’t understand how you could be a math teacher and be that bad at Magic.

…

So when you’re not born a champion, are there ways you can break your limits?

Even though all players don’t start on an equal footing regarding playskill, there are always ways to maximize your potential in an attempt to catch the better players in this world.

The key to improving your game, and breaking your limits, is to know where you stand on the “playing skill scale,” and to know the level you want to reach. If you can determine why you can’t make the right decisions during games, you will start to improve. Knowing the source of a problem is often the way to solve it.

While I haven’t seen many actually break their limits, examples do exist. We just have to look at the current Pro Player race to find the perfect one. With ten points, Julien Goron is leading this year’s competition.

Julien has been playing Magic for over seven years. He played his first Pro Tour last season, and finished it with thirty-six points, ending up second of the Rookie Race right behind Pierre Canali. He won French Nationals with a deck he had never played before, making up for his lack of playtesting with good playing skills. He also made it to the finals of the last two European Grand Prix tournaments, Hasselt and Dortmund.

Players, in general, blame their luck far too much. How many times have you heard “That lucky bastard topdecked the turn before he died!”…? At that point, they should ask themselves the following question instead: “Was there any way I could’ve killed him a turn earlier?”

As soon as Julien realized his limits, and that luck was an almost negligible factor at the highest levels, his determination grew… and he was able to break his level. Therefore, his potential improved, going from “Okay to Good” player to a “Good to Very Good” player. He started questioning his plays, and discussing them with the Pros. He knew his game wasn’t the best, and he wanted to do something about it. He also learned a lot from just watching them.

Of course, Julien’s case is exceptional – not everyone can train and have assistance from such players. But it shows that it’s not impossible to break your level.

You can improve your game, and optimize your playing skill potential, by playing, drafting, and reading online articles. In order to break your limit, you need a trigger. Anything that will make you realize what your level really is, and how well you want to play.

I don’t believe you become a better Magic player by just playing. It’s not a matter of time alone…it’s a matter of determination.

Know where you stand, question your plays, learn from pros, find your trigger, break your limits.

See you on the Pro Tour.