When Turbo Stasis blew the world away in 1996, Matt Place showed up at US Nationals with a deck unlike what nearly anyone had seen before, and Howling Mine became synonymous with “turbo” in the Magic world. He wasn’t the first to play the deck, but his Top 8 finish was perhaps the most noteworthy.

Lately I’ve seen a ton of press about the new coming of Howling Mine, Dictate of Kruphix, and there is a pretty great reason for that. Playing with Howling-style effects is exciting. Exciting like this:

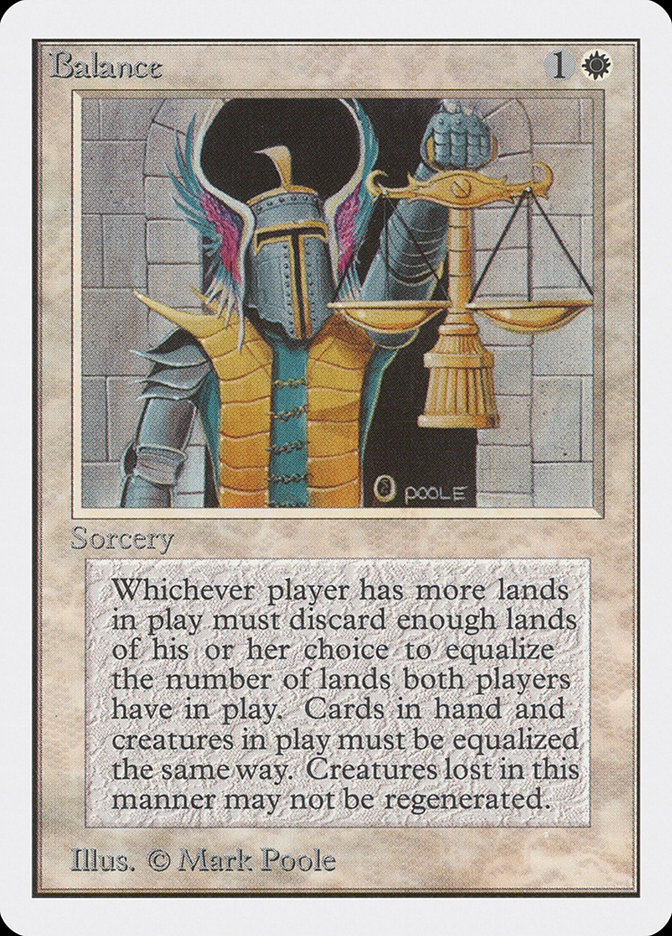

They are still wildly misunderstood though. One person I respect said that Dictate of Kruphix is really great for decks that have big effects, and that can be true but only if they are of a certain kind of big effect. However, this is not the mid-’90s. Big effects don’t cost almost nothing anymore. You don’t see this in Standard:

That is for good reason. Big effects costs mana, so most of the time neo Howling Mine decks have been written about by people that love Dictate of Kruphix, I’ve seen some fundamental problems.

Even among the oldest of veterans in this game, very few people remember this deck from the retro "November ’96 Type 2" (for some reason, a PTQ format that played as though we were in 1997):

Lands (5)

Spells (55)

During the Pro Tour Paris qualifying season, this deck was the best deck in Type 2 (what we called Standard back then). Originally designed by Pete Leiher, it was modified (primarily by Bob Maher and Andrew Nishioka) to be such a powerhouse that it literally won every PTQ it was played in for almost two months. You need to remember that at the time decklists were not widely disseminated, so other people didn’t exactly know what was in it.

Team ACD, the group of people playing it (a long-defunct Magic team from Chicago/Madison) broke it, and they ran the tables. I still remember one PTQ in Indianapolis where Chris Czuba showed up late and talked his way into the tournament at the very beginning of round 2. He started with a 0-1 record and a game loss, was paired against the player who had been awarded a round 2 bye, and went on to win the whole event, not losing a game.

It was only at the very end of the format that people began to be able to beat it.

But look at what the deck is doing just by examining the mana curve ("m" are cards that produce mana, and "k" are key elements to the deck’s function):

0: xxxxk = 5

1: xxxkkkkkkkm = 11

2: xxxxkkkkkkkkkmmmmmm = 19

3+: xxxx = 4

The only actual kill card in the maindeck was Howling Mine itself. The plan was just to run the opponent out of cards using Feldon’s Cane to replenish your own library and Enlightened Tutor and Mystical Tutor to set up this absurd combination:

Especially with how timing worked back then (there was an "interrupt window" after which if a spell wasn’t countered, other effects could be done but that spell was happening), Balance plus Zuran Orb was insane.

Even more than Turbo Stasis, Florida Orb was a deck that really broadcasts what can be scary about a Howling Mine deck—giving your opponent as many cards as they like, but having nearly all of those cards be useless because they won’t have time to use them all and won’t be able to do enough on any turn for you to care. Florida Orb is full of the kind of cheap spells that mean you will be able to accomplish what you like on any turn, and Force of Will (plus Arcane Denial) will stop whatever rare card someone might play to nix your plans.

With an effect like Dictate of Kruphix, you need to respect what it means to be choked for mana. Even without a Howling Mine effect, take the example of the so-called “Norwegian Stasis” (debuted at Pro Tour Chicago 1999), which ran no Howling Mine but ran Gush and Thwart to power itself. I updated the deck and made some changes that I thought were pretty radical, and then I gave it to Tony Dobson and Gary Wise for the New York Masters, one of the most prestigious events of the year. They chickened out a bit and put in Morphling, but they needed to play what they were comfortable with. Tony qualified for the Masters with it in the Gateway, and I later played it in PTQs, losing in the finals of one due to a play error against Miracle Grow. Here is that list:

Spells (60)

- 2 Stroke of Genius

- 4 Force of Will

- 3 Propaganda

- 4 Stasis

- 22 Island

- 4 Impulse

- 2 Boomerang

- 4 Gush

- 2 Daze

- 2 Foil

- 4 Thwart

- 1 Misdirection

- 2 Back to Basics

- 2 Spellbook

- 2 Claws of Gix

Sideboard

With the same notation as before:

0: xxxxxxxxxxxmmmmmmmmmm = 21

1: = 0 (but Stasis upkeeps might account for a ton here)

2: xxxxxxkkkk = 10

3+: xxxxxkk = 7

The Norwegian Stasis deck can expect that it is going to have a ton of cards in hand. In fact, it would likely have so many that I even ran this card:

Only it wasn’t as powerful and cost zero:

Between these decks and Squandered Stasis (a deck I co-created with fellow Cabal Rogue member Craig Sivils way back in 1997), I learned some valuable lessons about the idea of "card glut." Like in Florida Orb, if you’re going to have a ton of cards, you only want to have something expensive going on very rarely. "Powerful" effects can be a trap. If you’re going to spend a ton of mana on something, it needs to be doing something completely critical. In Florida Orb, if you spend nine mana in the late-late game on a Recall, chances are you’re bringing back to your hand three Force of Wills and a Balance. Even running only two Wrath of Gods (Bob would later cut down to one) is a bit of a stretch.

Cheap spells that negate the opponent’s plays are key. Obviously a card like Force of Will is best, but most of the time you won’t have access to a card of that power.

Let’s examine a successful Turbo Fog deck from only a few years ago:

Spells (40)

Again, let’s look at the curve:

0: mmmmmmmm = 8

1: xxxxxx = 6

2: xxxxxxxxxxxxxkkkk = 17

3: kkkk = 4

4+: xxxxxxxkkkk = 11

The top end of the curve is all potent cards that either fuel the engine of the deck (Tezzeret the Seeker, Font of Mythos, Jace Beleren) or can negate whole elements of what the opponent does (Wrath of God, Cryptic Command). I wrote about how these decks function a few years ago in “The Killing Fog: A Different Take On Standard U/W”:

While they may kill with Tezzeret the Seeker, they plan on primarily winning via decking . . . usually with Jace Beleren’s ultimate ability and occasionally from the simple effect of Howling Mine and Font of Mythos, each of which can collectively contribute to an incremental decking of the opponent (since they are affected first). An overwhelming number of Fogs cuts your opponent off from an entire path of victory.

Certain very powerful decks like Reveillark simply could not fight this fight because by the time they could martial any real path to victory, Howling Mines would be set up with a large amount of countermagic available to prevent the very few cards that mattered. While a Reveillark deck might not have normally cared if you suppressed their creatures, there was simply so much nullification from Turbo Fog that even if it was temporary Reveillark couldn’t begin to fight it.

Building your deck to maximize this kind of effect is important. Global effects like Howling Mine and Dictate of Kruphix fundamentally alter the nature of what is happening in the game. "Draw a card" is the rule in Magic, and once you mess with this the balance of how games go shifts. If you’re going to actually take the time to play a Howling effect, you absolutely need to recognize that the reason it is worth your time is that your deck is set up for the new reality of the game and you get an advantage because your opponent’s deck is not.

Longtime friend and collaborator Ronny Serio claims that this next deck is the best deck he and I have ever made together. I won a number of very minor events with it and lost in the last round of a US Nationals Last Chance Qualifier with it:

Creatures (1)

Planeswalkers (3)

Lands (22)

Spells (34)

Again, let’s look at the curve:

0: m = 1

1: xxxxkkkk = 8

2: xxxxkkkkkkkmmmm = 15

3: kkkm = 4

4+: xxkkkkkkkk = 10

In terms of "negating the opponent’s play," this one functions as a Turbo Time Warp deck; there is very little that removes their play better than denying them one at all! Silence was another part of that package. The "key elements" at the top of the curve make this deck function, while the other two cards (Jace, the Mind Sculptor and Martial Coup) each had a very specific function for closing up loopholes that might otherwise be left open.

All of this history comes with a purpose in mind—understanding what an endless "each player draws another card" means.

Let’s consider some guidelines for decks that want to go "turbo."

First of all, cards are going to be an abundant resource. This might sound obvious, but it means a lot.

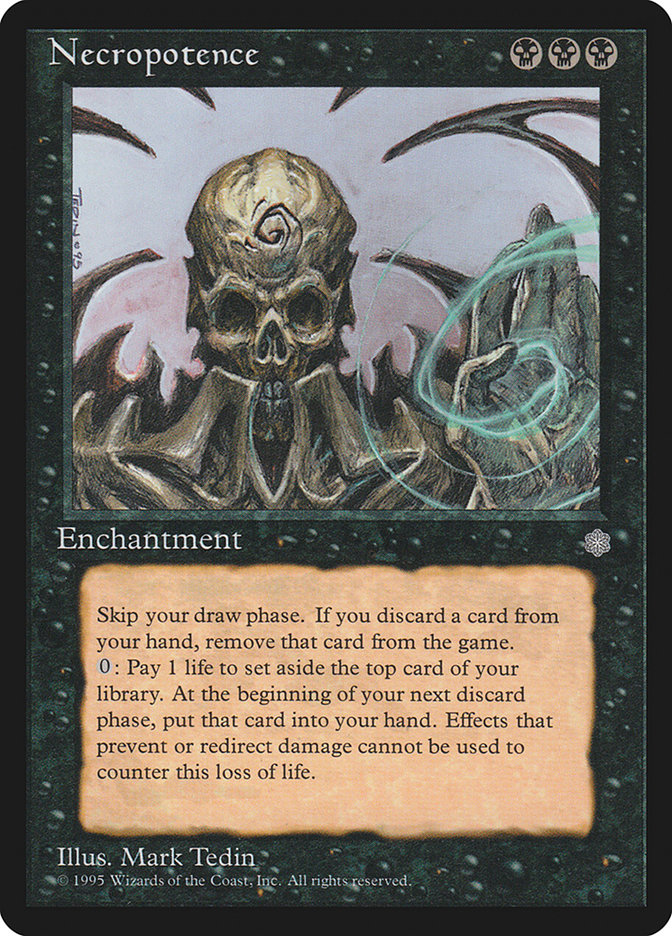

Back in 1996 one of the most important card advantage cards of all time dominated Magic:

While it was initially misunderstood, it eventually became so prevalent that the tournament scene referred to the era as "Black Summer." Howling Mine was the reason that Turbo Stasis was able to fight Necropotence decks; it simply didn’t matter if Necropotence had a powerful card advantage engine because cards were abundant under Howling Mine. Today this is the new Necropotence:

Take an example that we see in Sphinx’s Revelation mirrors all the time. Player A untaps, draws a card, and says "go." Player B successfully casts a Sphinx’s Revelation for six, untaps, doesn’t have much to do, and says "go" (discarding a card).

Initially, this is likely to be a devastating moment. Even with the discard card, compare their respective card advantage from the point where it goes back to A’s turn.

Player A: +1 (draw phase) = 1 card up

Player B: +1 (draw phase) +5 (Sphinx for 6) -1 (discard phase) = 5 cards up

If the game goes on without any further card advantage changing, Player B will still be ahead four cards. However, how important that is slowly diminishes over time. At first for example being up four cards is huge, as Player B has outdrawn Player A in that portion of the game a great deal—Player B has 500 percent the cards Player A does. In five more turns, however, Player A will be up to six cards, and Player B will be up to ten—only 166 percent. The weight of the advantage diminishes.

In a Howling Mine / Dictate of Kruphix deck, this effect is magnified in speed, and it happens immediately.

Player A: +2 (draw phase) = 2 cards up

Player B: +2 (draw phase) +5 (Sphinx for 6) -1 (discard phase) = 6 cards up

Without anything else changing, you can see that the immediate advantage for Player B is only 300 percent. Realistically, though, it is likely that Player B will be discarding more cards (I’d expect that at least two)—with only two cards being discarded, we’re down to 250 percent immediately (half the advantage of a non Dictate of Kruphix situation). In the more realistic situation, if we go to five more turns, Player A will be up twelve cards, and Player B will be up fifteen—down to 125 percent.

I know that for some of you math (and history) can be boring, but it really matters when you’re trying to play a card like Dictate of Kruphix. If you’re putting Sphinx’s Revelation or Divination into your Dictate of Kruphix deck, it’s likely that you’re doing it wrong. All of the little advantages you get from the card are being diluted.

The fact is that Dictate of Kruphix is good against Sphinx’s Revelation. (This mirrors Howling Mine versus Necropotence.)

Even worse in conjunction with Dictate of Kruphix are cards that draw fewer cards like Divination. There are going to be tons of cards available but only so much time, so spending our time to get even more cards is often a waste.

Other exceptions can only work in very specific contexts. When Patrick Chapin invented Turbo Time Warp, he ran both Recall and Prosperity. In his deck, though, Prosperity only worked because he could immediately shut down the opponent’s next turn through Exhaustion or casting Time Warp; in addition, he used Helm of Awakening and Sapphire Medallion to be able to shoot off multiple plays per turn. Bob Maher with Florida Orb used Recall exclusively to bring back numerous Force of Wills and absurd cards like Balance. In both cases, they were setting up the possibility to make a lot of plays in a turn (though Bob was planning on using his cards on the opponent’s turn).

Secondly, if cards are abundant, you need to play yours better than your opponent.

One of the things that all of the above lists have in common is that they have both a ton of cheap cards and a ton of ways to shut down entire categories of play from the opponent. Koji Takanashi’s Regionals-winning Turbo Fog could endlessly shut down the attack phase. Stasis and Florida Orb decks could shut down the mana of the opponent. The various Time Warp decks could steal away the turn.

Shutting down a turn is quite difficult in current Standard. But you can play spells that have an ongoing effect that can influence a game. Sometimes this is easy; a Blind Obedience or a Sphere of Safety will have an ongoing effect you only have to pay for the one time. At other times this can be quite difficult. For example, is a planeswalker worth it? It’s a complex question.

A card like Jace, Architect of Thought is an interesting example of pressures in opposition. Drawing cards with Jace is an advantage that is watered down by Dictate of Kruphix. On the other hand, the +1 ability on Jace can be an effective way to negate a large number of cards. Given especially that this effect won’t require any extra mana to keep using makes it even more likely to be good. Overall, I’m not a hundred percent sure that this balance weighs in favor of Jace or against Jace, but it is still worthy of consideration. Elspeth, Sun’s Champion seems even more likely to be correct, but it still isn’t necessarily a slam dunk; the card is very expensive, and it simply might not accomplish enough in a mana-abundant game.

Aside from running permanent effects, lots of cheap spells can sometimes mean that you actually get to make use of what you’re getting into your hand, while your opponent is not. There may currently be enough Fog effects for this to be an idea.

The third thing to consider is your opponent will find the cards that execute their game plan.

Having everyone draw extra cards means that whatever it is your opponent expects to do in a game will just naturally occur. Mana screw can still happen, but it tends to not happen nearly as much. A burn deck will rapidly draw all of the cards that they need to beat you. A black devotion deck will find Gray Merchant of Asphodel. Blue decks of all sorts will find their counterspells.

You need to be prepared for this.

This means that especially after board you should be prepared for whatever their game plan might be, particularly for the things that shut down Dictate of Kruphix. Is it going to be Detention Sphere? Is it going to be Deicide? Unravel the Aether? If you’re playing a deck that leans on Dictate of Kruphix to function, you better be prepared to not only answer the expected game plans of your opponents but also their answers to Dictate of Kruphix.

I’ve only just begun working on the following deck so it isn’t honed, but I think it expresses many of the ideas that I just talked about. Howling Mine decks are not necessarily well positioned in a metagame, so this might not be the best choice for SCG Standard Open: Cincinnati this weekend. However, Howling Mine decks can be overwhelming at the right moment.

Here is my brew:

Creatures (4)

Lands (12)

Spells (44)

While I’m planning on playing a more traditional U/W Control list in Cincinnati, I’m actually really excited about exploring Enchanted Prison. I’m a big fan of decks that hit a metagame sidewise, and this takes a very novel approach to the challenge of Standard.

We won’t know what that metagame is until more events are in the books, but if you’re as excited about Dictate of Kruphix as I am, make sure you actually understand what it means to have your deck be turbocharged. A Dictate of Kruphix / Howling Mine deck isn’t like other decks, so learn the lessons of history and don’t get caught with your wheels spinning in a ditch.