After emerging during the Magic Online Championship Monthly Qualifier,

white aggressive decks, most splashing red for Heroic Reinforcements and/or

sideboard cards went on to dominate the Pro Tour last weekend, which, for a

person who has been glowing over the cards History of Benalia, Conclave

Tribunal, and Venerated Loxodon for months now, was great to see.

When

The

Chainwhirler

is away, the X/1s will play.

It may not have come via the Selesnya Conclave I have likewise championed,

but it’s clear that the tokens are still quite viable, along with Mono-Red

Aggro, Jeskai Control, Golgari Midrange, and Izzet Drakes. But the Boros

Aggro decks are the relatively new kid on the block, and the rush to

understand how to combat them or adapt to being the new bogeyman, depending

on your prerogative, is on.

What I want to focus on today, is the mirror match. The Pro Tour top 8 was

filled with them, and while that did lead to some fast games, those games

were filled with small, tactical decisions as both players jockeyed for

position, trying to maximize their own attacks while minimizing their

opponent’s.

The man who emerged victorious from this combat-centric top 8, Andrew

Elenbogen, made an interesting point in his winner’s interview, which you

can view here:

Watch Pro Tour Guilds of

Ravnica End Step: Final from Magic on www.twitch.tv

Andrew’s remark here is critically insightful, and if you go back and watch

the various white mirrors, you’ll see instances where the players are

willing to trade say, a Skymarcher Aspirant for a Dauntless Bodyguard, and

times when they aren’t. The decisions of whether or not to trade in defense

or offer a trade on offense were important in every game and dictated how

they played out.

For inexperienced players, the question of whether to trade one card for

another often comes down to a simplistic evaluation of which card is better

in the abstract. In that model, trading a Dauntless Bodyguard for a token

from History of Benalia would be bad because they’re trading a full card

for half a card, while trading that same Dauntless Bodyguard for a Ajani’s

Pridemate is good because the latter is a more powerful card. This line of

thinking is a useful guideline, but is overly simplistic, as there are many

more variables at play in the decision since a card’s value is always

contextual to the gamestate.

Today, I’ll be unpacking this question in a general sense and looking at

the specific factors that go into answering it within the context of the

Boros Aggro mirror. One thing to keep in mind while reading is that this is

a dynamic question, that is one whose answer can change as the game

progresses, often multiple times, so you can’t answer it on turn 3 and move

on. Answering it each turn as the game changes is challenging, but a

surefire way to gain an edge in this mirror, as well as aggro mirrors in

general.

The Basics

At its heart, the decision of whether or not to trade is an exercise in

role-assessment. Trading resources is likely to force the game to go

longer, which makes sense if you’re trying to take a controlling role.

Conversely, taking an aggressive posture will require finding the attacks

that make trading as bad as possible for the opponent.

But when both players are playing similar decks with lots of overlapping

cards, and those cards are meant to be hyper-aggressive in the abstract,

it’s unclear which player should be more controlling from the start. The

first variable is who is on the play versus the draw. When your creatures

naturally want to be attacking, getting to attack first is the tiebreaker.

As long as both players are maintaining parity, the player going first will

want to press their advantage as much as possible while the player on the

draw will want to bide their time and be more apt to trade until they can

leverage their extra card to gain a clear advantage on the battlefield.

However, that qualifier, “as long as both players are maintaining parity”

is hugely significant. It doesn’t take long for a player to take a huge

advantage if their opponent stumbles, whether from missing a land drop, not

using all their mana, or failing to have an answer to a powerful card like

Benalish Marshal. As soon as one player gains an advantage on the

battlefield, whether on the play or draw, they become the aggressor.

to trade is an exercise in role assessment.

To this end, it’s important to evaluate how strong your hand is over the

first three to four turns of the game and judge whether or not you’re

likely to have the advantage at that time, with the play/draw variable

serving as a tiebreaker if you think both draws will be roughly even in

quality.

The last factor to consider here is who has the deck advantage in the early

game vs the late game. A list that goes bigger with cards like Aurelia,

Exemplar of Justice, Experimental Frenzy, and Lyra Dawnbringer is going to

want to draw out the game and leverage the power of those cards, while a

deck with more cheap creatures and finishers like Pride of the Conquerors

and Heroic Reinforcements will want to keep the battlefields large to make

those cards more impactful.

Evaluating this variable requires a fair amount of homework, researching

what different lists look like so you can make more reliable judgments from

the cards your opponents play early, but as the game goes longer, you’ll

want to keep track of what powerful cards have been played so you can

reasonably judge whose deck is more dense with powerful cards since it’s

that person who will be advantaged if the game progresses further.

The Specifics

Of course, these guiding principles are always going to be just that, a

guide. The cards themselves are the ultimate governors of the matchup, and

as we saw at the Pro Tour, understanding how to leverage them in accordance

with these principles is the key to the mirror.

The individual creatures are mostly interchangeable, though we’ll get to

the most important ones later on. Here I’ll be focused on three categories

of cards that every Boros Aggro deck was playing in some numbers: anthem

effects, the armies in a can, and the one-shots.

These are the primary anthem effects, by which I mean permanent buffs to

your creatures. They are the most important cards in the matchup because

the player with the larger creatures is going to dominate combat and thus,

win most games.

The obvious answer is that because they pump all your creatures, that you

won’t want to trade early so that their effect will be maximized. This

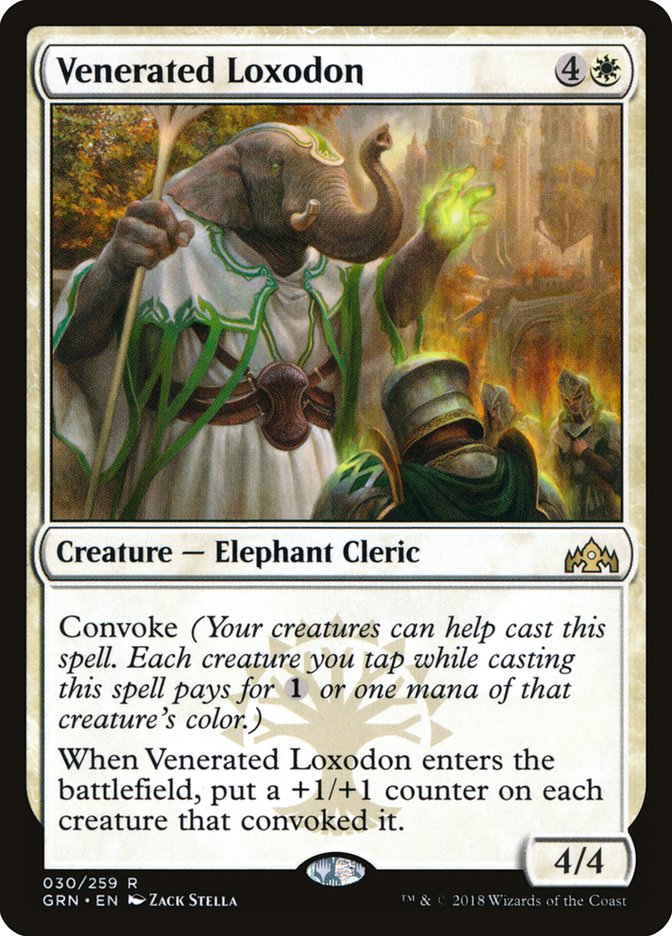

tactical pull is even stronger for Venerated Loxodon since each creature up

to the fifth makes it potentially cheaper to cast.

However, each of these creatures takes a significant cost to cast, with

Benalish Marshal often taking an entire turn of mana and Venerated Loxodon

requiring both mana and taking several creatures out of combat for a full

turn cycle. If cast haphazardly, you may open a window for your opponent to

make a large attack and either leave you unable to stave off death or

forced to leave your army back and give your opponent time to draw anthem

effects of their own to level the battlefield. If you’re dead or your

creatures can’t effectively attack, it doesn’t much matter how much larger

they are than your opponent’s.

With Venerated Loxodon, you’ll want to consider how many creatures you need

to leave untapped to play defense, knowing that once you untap you’ll be

quite far ahead, and any creature you would leave untapped anyway can be

traded off early without any loss. That trade can even be beneficial by

cutting off the potential for your opponent to double-block your larger

creatures, so be sure to trade off for higher toughness creatures if

possible – a Knight token is more valuable than a Skymarcher Aspirant here,

for example.

With Benalish Marshal, the consideration becomes the loss of tempo against

a removal spell removing the buff. If you try to slam a Marshal on turn

three and attack, you could be immediately put on the back foot while

unprepared to play defense and if that potentiality is dangerous enough,

it’s worth making an early trade or two knowing that you can press your

advantage with Benalish Marshal a turn or two later.

In essence, what you’re doing here is evaluating the diminishing returns of

your next pumped creature or two against the potential for your opponent to

go for a quick kill, knowing that your anthem advantage will quickly

snowball. The more behind you are when casting the anthem will be the

determining factor. The more behind you are, the more opportunity your

opponent has to capitalize on their window to put you at a precarious life

total, so the key here is to try to keep the battlefield relatively stable,

so that the anthem effects do maximum damage at minimum risk.

These are the army in a can cards. They both provide multiple bodies in one

card and as a result, are generally amenable to trading. Card advantage is

perhaps the oldest principle in Magic and making multiple bodies that can

each trade for one card from your opponent is a classic example of it in

action. Combined with other trading and you can run your opponent

completely out of threats and clean up the game with whatever’s left when

the dust settles.

But both of these cards have aspects of them that encourage keeping

creatures on the battlefield. For History of Benalia, it’s the third

chapter providing a potentially devastating attack. The 4/3 Knight tokens

are difficult to block effectively and can lead to an even better trade

down the line should your opponent’s life total be low enough. This set up

is even more powerful if you have the “combo” of History of Benalia and a

second copy of History of Benalia for the back to back big attack.

With any kind of token maker like History of Benalia, the instinct is to

trade off those tokens because they are only half of a card, but on the

battlefield, a 2/2 vigilance Knight is often better than any one-drop

because vigilance lets you play offense and defense simultaneously, and the

second point of toughness means Knight tokens accept anthems more

effectively. So if you are trading, I’d look to trade the smaller creatures

rather than the tokens that are generally more effective on their own and

going to have at least one turn of attacking for two more damage.

With Legion’s Landing, the impetus to trade creatures doesn’t actually come

until Adanto, the First Fort is online, which means attacking with three

creatures to transform it. This often means not trading too early, and in

some cases throwing away the Vampire token, which is a detriment to any

attrition plan. In practice, a key aspect to the card is the ability to

generate an extra land in the early game, thus providing a significant

tempo advantage that you can press by becoming the aggressor.

It’s not until the game goes rather long, many creatures have traded, and

you have mana to spare that the token generation comes into play, and in

these mirrors, it’s the early game that’s more important. So rather than a

lategame, attrition card, I’d be apt to view Legion’s Landing as a 1/1 +

Rampant Growth, which is a decidedly aggressive card that will

disincentivize trading in the early game outside of the turn you transform

it.

Lastly, both of these cards serve as important enablers for the ascend

mechanic. Skymarcher Aspirant is ubiquitous, and many lists play Snubhorn

Sentry as one of their many one-drops, and both creatures are very powerful

with the city’s blessing. Declining a trade to get to ten permanents could

pay significant dividends later on in the game and is something you should

be aware of when making these decisions.

And finally, the one-shot effects. Much like the anthem effects, these are

most effective when the battlefield is clogged with creatures. With enough

attackers, they can threaten lethal damage quite early on and force the

opponent to take a more defensive posture than they would’ve liked or force

them into a bunch of bad blocks, devastating their position.

But unlike the anthem effects, the fact that these stop at the end of the

turn makes them ineffective on defense. In fact, the ability to threaten

these effects is one of the reasons why the aggressive player doesn’t want

to trade early.

But, as one player falls far enough behind, stealing a game with a single

big attack becomes the only viable path to victory. Trying to extend the

game via trading will only delay the inevitable once the advantage on the

battlefield is large enough, so trading becomes disadvantageous even for

the defensive player. At this point, you enter a subgame where the

attacking player wants to attack in such a way to maximize their clock

without leaving themselves dead to a topdeck.

You can see this subgame in action during

game four of the semifinal match between Jeremy Dezani and Luis

Scott-Vargas

. Falling behind early while on the draw, LSV stabilizes behind the power

of Benalish Marshal and Healer’s Hawk undoing much of Dezani’s damage

output. At that point, Dezani is behind on the battlefield and without an

answer to the fliers, so his best chance is setting up one large attack.

LSV recognizes this, stops attacking with anything but the Hawks, even

though Dezani’s blocks wouldn’t have been favorable. With the added

blockers, neither Pride of Conquerors nor Heroic Reinforcements would’ve

ended the game. A weaker player may have gotten too aggressive and given

Dezani a window to steal it.

The Best Defense is a Good Offense

I mentioned above that the creatures are mostly interchangeable, with some

exceptions. Those exceptions are any creature with one or more of the

following keywords:

- Vigilance

- Flying

- Lifelink

These abilities allow a creature to play offense unabated or play offense

and defense simultaneously, both of which are highly advantageous. The

common thread in everything discussed here is optionality – that is keeping

your options open while simultaneously limiting your opponent’s. With a

lifelink creature, you can more freely let your opponent attack if your

blocks aren’t favorable, which we saw LSV do many times in his matches on

Sunday. With air superiority, you have automatic offense, allowing you to

devote more resources to playing defense on the ground. And with vigilance

creatures, you have two-way players so you can make bigger attacks with

less worry about a counterattack.

All of these abilities open up options for you, making offense easier for

you and harder for your opponent–which is the same as making defense

easier for you. We talk about these concepts as distinct entities, but the

truth is they are all interrelated, and it’s important to know and exploit

those interactions.

here is optionality – that is, keeping your options open while

simultaneously limiting your opponent’s.

It would be nice if all of these principles could be organized into a flow

chart of sorts that maps out any given decision, but Magic is far too

complicated for that. As long as neither player is dead, then there are no

sure things and everything has a touch of gray. So the best thing you can

do is equip yourself by knowing and understanding all the variables that go

into the complex decision-making inherent in Magic. Moving forward, I hope

you all feel better equipped to approach the Boros Aggro mirrors that will

undoubtedly be quite popular over the coming months.