Your heart is pounding.

At this point, it’s unclear who’s going to win, but you’re definitely ahead. You made a massive comeback after earlier mana screw, but now the game could go either way. The match is going to be decided on this turn. You just need to stay focused. Can you play around X? What about Y? If they have Z, it’s going to be hopeless, so there’s no point in playing around that. If I play around X, it gives them more time to draw Y, so it’s a wash.

Your heart’s still pounding, but you love it. This is the best part. You get to let go.

Exhale.

It’s not up to you anymore. This is the play that gives you the best chance of winning.

You make a carefully crafted attack where you can survive at exactly one life if they alpha strike. If they have it, where it is basically anything, you’re dead. If not, they can’t attack at all. They can bluff a trick in the hopes of deterring you from attacking, and hell, maybe they even drew it. Either way, you still have no choice.

“Attack with everyone.”

Play Without Fear

Games of Magic are typically close, but our natural instinct is to make them less close. Trying to play around things, making sure you don’t die to a certain combination of cards, and trying to be in control of the game at all times are all things that, if done correctly, are the mark of a good player.

At times it’s foolish. Playing around Act of Treason opens the door for them to draw Lava Axe, especially since now you’re giving them another turn. If you play around a combat trick by not blocking with your excellent creature, you’re taking extra damage that could result in dying to Lava Axe.

Embrace the razor-thin margins.

If you only played pots in poker where you knew you were going to win, you wouldn’t win very much. Games are rarely a lock. In fact, the outcome of a game is typically in question until the very end. You’re going to need to take some risks in most games.

No one wants to lose and no one wants to look foolish in the process for taking risks, but it’s necessary. It’s that fear that holds people back at times. Your best option is often to engage in a racing situation.

Playing to not lose isn’t a path to victory, and Modern exemplifies this beautifully.

Go Time

Do you kill their Blighted Agent on your turn 2 or play your Tarmogoyf and start racing? If you don’t get a clock on them, they get way too much time to find another threat or the protection spell they need. Could you die on turn 3? Absolutely, but would you rather try to win a close game or avoid dying for a turn or two? Chances are, they don’t have it. Even if they do have it, you’ll be in the same spot once they play another creature.

Ignoring the fact that they could kill you on turn 3 is foolish, but it is so rare, the odds that preventing the potential turn 3 kill will actually translate into a victory are slim. It’s about taking risks, but only ones that are calculated.

On the other side of the coin are the players who could navigate into a close game but go for the win instead. “If you have it, you have it.”

Have they ever not had it in that spot? Of course your opponent has it, but instead of trying to maneuver in a difficult battlefield state, they’ll take the easy route. It almost never ends up in victory, but they’d rather simplify the situation and end the game, no matter who wins.

Some players are better are processing complicated battlefield states. Others crumble under all the variables and inevitably miss a double block or something similar that makes their play much worse. Being able to recognize your strengths and actively work toward situations where you can capitalize on them is something not enough people do.

There are a subset of close games that are more than just racing situations. In these, you actually get to pace the game, close off your opponent’s outs, and win despite being at a supposed disadvantage.

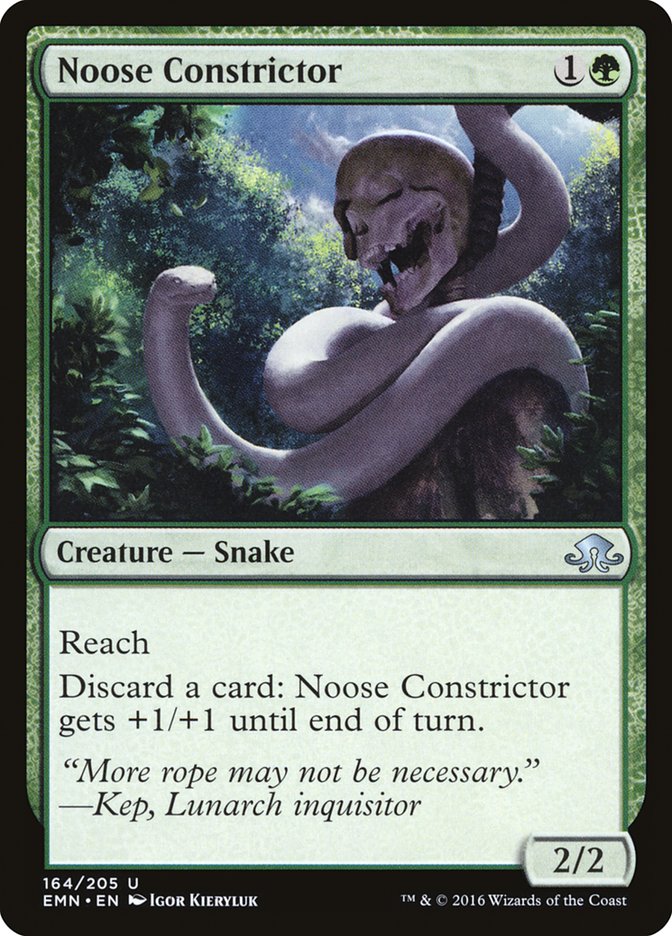

Skills learned from piloting those games can be utilized in games you’re ahead in also. By slowly closing off their outs, you’re tightening the noose. They’re dead already but don’t know it, as long as you don’t give them the opening to come back.

Tightening the Noose

There are four types of games you win.

1. You smash them.

2. You tighten the noose by slowly playing around their outs because you have the luxury of doing so.

3. You’re behind but play to your outs the best you can.

4. The game is back and forth, but you win a tight race, topdeck war, or outplay them.

Of these, “tightening the noose” games are the most intricate. Any misstep could cause the entire house of cards to collapse.

Sometimes, the best way to tighten the noose is to let up. Your opponent is typically betting on you to make the obvious play, so play around it.

Scenario #1

In a Khans of Tarkir / Fate Reforged Sealed PTQ on Magic Online, I had a great deck and a great start in Game 3 of my first match.

After some cheap creatures and a couple of removal spells, my opponent was on the ropes. They had no battlefield and were at ten life or so, and I had three power on the battlefield. Their turn was simply “land, pass.”

On my turn, my only decision was to cast Kolaghan, the Storm’s Fury or not.

With the mana my opponent had available, I couldn’t think of a removal spell they could have with their Temur mana and empty battlefield. A counterspell was possible.

In the end, I knew holding Kolaghan was likely correct, but couldn’t think of a reason not to cast it. Return to the Earth was a card I forgot existed, but could have played around. I was ahead and they’d have to tap out eventually to deal with what I had at some point.

Walking into their tricks is what they need you to do in order to win.

Scenario #2

They know I have Valorous Stance from an earlier Thoughtseize.

They’d been missing some land drops. So had I.

Given this spot, it’s reasonable for me to assume they have Abzan Charm. Would they hold open Hero’s Downfall, knowing I had the Valorous Stance?

My options are to cast Mantis Rider and attack or not. Either way, I’m not attacking with Dragonlord Ojutai. If I cast Mantis Rider, they could Abzan Charm it, which might be nice, because it could free up my Ojutai to start attacking.

If I don’t cast Mantis Rider, they could use Abzan Charm to draw two cards, potentially hitting some land drops. That could enable them to develop their battlefield while still representing Abzan Charm.

They could also use Elspeth, Sun’s Champion to take out Ojutai. I could attack it down with Mantis Rider or put them to three if they used Abzan Charm to draw two cards.

Either way, I think I’m in a decent spot by sitting on Mantis Rider and making them waste their mana and/or Abzan Charm.

Scenario #3

There was also the situation of Brad Nelson beating down Willy Edel in similar spots with a Goblin Rabblemaster. On a key turn, Brad didn’t attack with Goblin Rabblemaster because Willy represented Abzan Charm.

These spots could potentially backfire if they don’t have the card you’re playing around, and maybe you miss out on a bunch of damage. What if Willy didn’t have Abzan Charm and had Elspeth, Sun’s Champion or a topdecked sweeper instead?

Building Around Tightening the Noose

My W/U Humans deck from the Invitational was excellent at tightening the noose. Sometimes I’d make a three-toughness creature to weaken a potential Kozilek’s Return, a four-toughness creature if they had Radiant Flames, or a planeswalker against their Languish.

Sizing mattered a ton, and it was all about lessening the impact of their big plays. Tightening the noose was actually my win condition.

Against creature decks, sizing was how you beat them too. Make a 4/4 to their 3/3 and attack, but not give them a reasonable double block when they added a 2/2 to the battlefield. Eventually you’ll find another Glorious Anthem effect or Reflector Mage and be able to make profitable attacks again.

Sometimes I’d want to clear the battlefield a bit against a potential Archangel Avacyn or engage in a race when I was light on resources and their hand was flush. Most of the time, it was about maintaining traction.

Traction

It seems like every couple years we come up with new terms that mean something new but are related to an already existing concept. In this case, I’m talking about traction.

Traction stems from tempo, but doesn’t necessarily mean the same thing. The crux of it is maintaining a stable battlefield position so that something like a Gideon, Ally of Zendikar or Reality Smasher (you know, game-changing cards) can’t shift the game in your opponent’s favor.

Traction is basically a form of tempo that is gained and maintained, which then potentially snowballs. In a sense, it’s about a tempo advantage that also negates your opponent’s ability to gain a tempo advantage.

Layering

I bring this up a decent amount, but most decks don’t do the same thing every game. Maybe you’re on the draw and your mana isn’t cooperating, putting your Bant Company deck on the back foot. Maybe your B/W Control deck is light on action, so your only hope is to get aggressive with Gideon, Ally of Zendikar.

These situations happen frequently, and being able to identify situations where layering your deck with a card that provides another angle of attack is valuable. While no one should build their B/W Control deck with aggressive elements at the forefront of their mind, you should at least be prepared for these situations and potentially include some cards that are hedges — good whether you’re ahead or behind.

Secure the Wastes is a card I cut numerous times because of how ineffectual it was on average, but it does add a new dimension to the deck, and situations where it’s useful come up often enough to warrant its inclusion.

Some decks should not be layered, such as Boss Humans. Others, like Abzan Control with Siege Rhino and Bant Company, have most of their power level tied up in creatures that can be proactive, reactive, and their sources of card advantage. B/W Control is similar to those decks because, while it has some card advantage in Read the Bones and Languish, it doesn’t have anything huge that puts them at a massive, unsurmountable advantage. The point where you say “B/W can’t lose this game” is when they have a Kalitas, Traitor of Ghet or multiple planeswalkers on the battlefield.

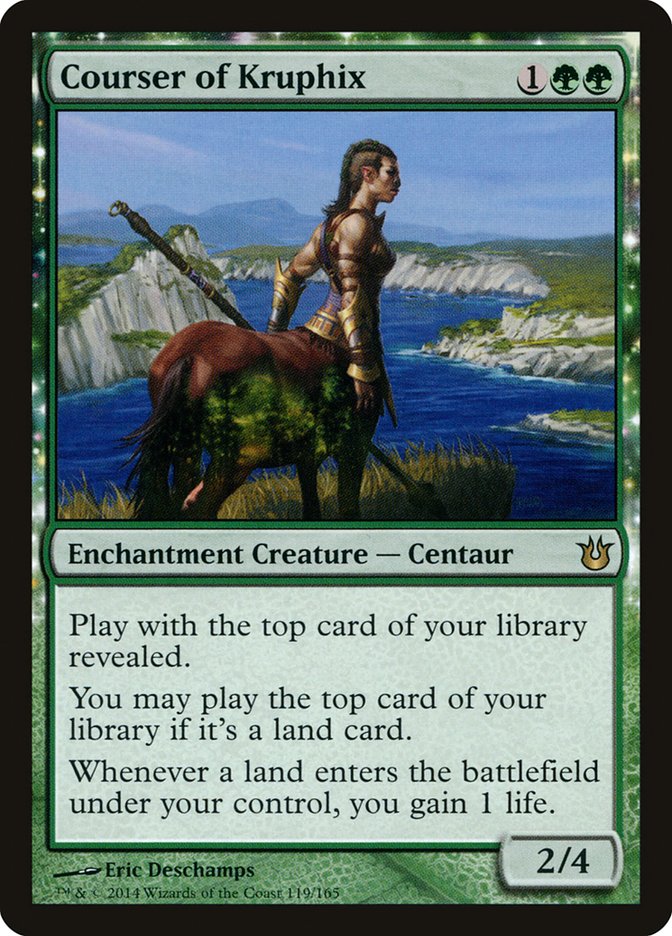

Abzan Control could sculpt the game with Courser of Kruphix all the way up to Ugin, the Spirit Dragon, gaining card advantage with Read the Bones and Abzan Charm, but that was just about as likely to happen as casting two Siege Rhinos, smashing the opponent for a bit, and then finishing them off with Ugin’s +2.

Ask yourself, “Is my Plan A always going to be good enough? What are the types of games my deck could end up in? Is it worth it to remove a card that helps my Plan A for something to hedge against other scenarios?”

Tying It All Together

Each of these scenarios has one thing in common: being able to identify the game state. It’s all that matters.

In essence, figuring out “Who’s the Beatdown?” rules everything. That hasn’t really changed, but the reasons have. In Constructed, there are very few decks that have inevitability, so deciding who is the control deck is far more difficult.

A deck like Jund Delirium is going to have to go beatdown on Bant Company far more often because the games are always in question. If you’re not attacking with your Distended Mindbender, there’s a very real chance Bant will draw a Tireless Tracker or Collected Company and start playing the control role better than you.

Ask yourself, “What’s going on in this game? What does the game look like when I finally win? How could my opponent stop me from doing that? Can I play around that plan?”

Consider “Who’s the Beatdown?” not only during gameplay but also when building your deck and planning for specific matchups.