Working for StarCityGames.com can be scary sometimes. You work for the best in the game, you’re surrounded by the best in the game, and you never feel quite good enough to be in the same conversations as other people.

Even with all of that being considered, it feels good to get praise from my boss(es) from time to time, and I don’t always get their applause, but when I do, it’s when I show up to an Invitational with Hexproof in Modern.

The last time I told you to just play something, it was about one of the scariest Standard decks to be legal in a long time. Today’s “best deck” (Bant Company) was laughable in the face of Rally the Ancestors. Make no mistake, Hexproof isn’t on the same level of “Tier Zero” that Rally the Ancestors was, but it is incredibly well-positioned in the current format and deserves significantly more camera time than it is getting.

I really don’t doing single-deck walkthroughs that don’t have some sort of overarching theme or attempt to reinforce some core fundamentals. This week is different. G/W Hexproof is scary. I wouldn’t even know how good the deck is if I hadn’t been trying so hard to make a metagame call for the #SCGINVI.

Most of my justification for wanting to play the Hexproof critters revolves around the deck being relatively linear, proactive, and something that most people aren’t packing the tools to properly interact with right now.

With the horde of Dredge that is surging around Modern (and with the hype surrounding the deck after Ross Merriam’s Open win with the archetype), Hexproof also had three big things going for it.

1. Hexproof gained another positive matchup in Modern. Hexproof doesn’t even need hate cards to beat Dredge. The draws that Hexproof loses to are the games where Dredge has ten power on the battlefield by the second turn, and nothing short of Grafdigger’s Cage helps anyway.

2. People are concentrating more slots in their sideboard to deal with Dredge, and Hexproof doesn’t interact with its graveyard at all.

3. Liliana of the Veil gets a lot worse against a deck that plans to discard all of the cards in its hand.

Despite having played exactly zero games with the deck (outside of some pickup games against Robert Wright the day before the tournament), I felt confident in the deck choice and (wrongfully) assumed the deck would be easy to pilot.

Despite my lack of experience, several misplays, and too-few reps to justify building my own deck, I did earn a prize at the Open held next to the #SCGINVI with the following list:

Creatures (12)

Lands (19)

Spells (29)

Most Hexproof lists are fairly locked-in (see: the eight green one-drop creatures) but there are a lot of aspects that change from list to list and are worth diving into.

Hexproof lists generally have a two-drop creature that is either Kor Spiritdancer for explosiveness or Silhana Ledgewalker for consistency. As Todd Anderson outlined last week, Modern has a lot of decks that just try to combo or kill the opponent as quickly as possible without interacting. Because of these decks, Kor Spiritdancer is an absolute necessity.

Against Infect, for example, it is rare that a Silhana Ledgewalker will produce a fast enough clock to kill the opponent before they deal ten points of poison to you. Kor Spiritdancer can be played in such a way to minimize the impact that most removal spells will have on her, but Silhana Ledgewalker can really only be so aggressive when it costs more mana than the other creatures in the deck while fulfilling a near-identical role.

Game 1 is also when most decks in competitive Magic are as streamlined as possible and killing the opponent can be more important than preventing them from interacting with you. Against decks that try to interact more with Hexproof, it is common to sideboard out some number of Kor Spiritdancers in order to bring in cards that better interact with the opponent or make their cards interact more poorly with yours.

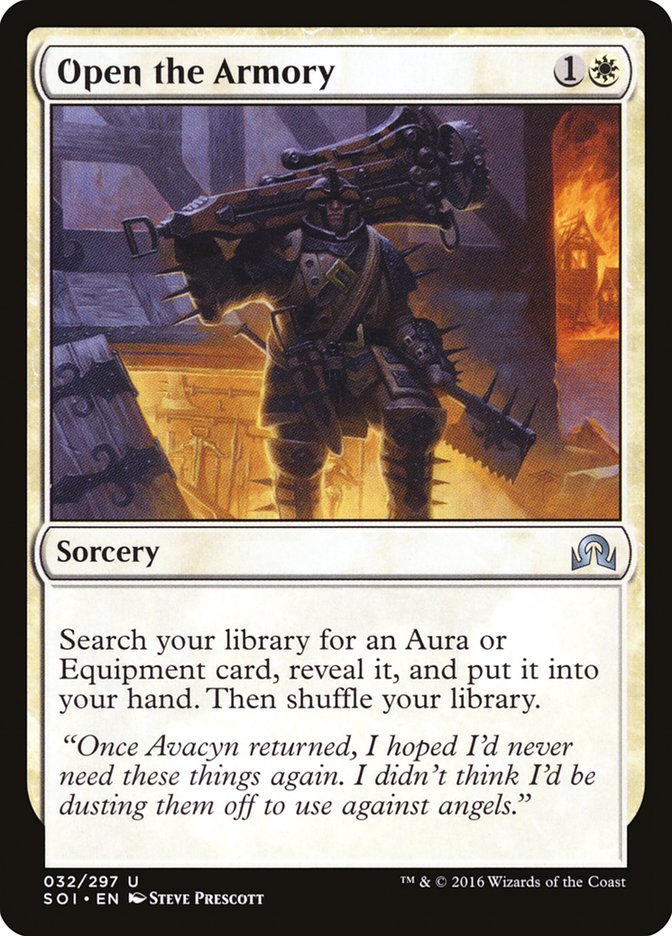

This is a card I was originally very high on when Shadows over Innistrad first hit the shelves. It allowed the deck to have a sort of toolbox-y feel to it while still being an aggressive and linear deck. There are a number of times that Open the Armory is merely a fifth copy of Ethereal Armor or Daybreak Coronet, and that’s just fine.

The second Dryad Arbor is kind of like The Spanish Inquisition. Dryad Arbor also often serves as a creature that can be grabbed with a Windswept Heath or any other fetchland in the deck. Against something like Dredge, it doesn’t really matter if the creature has hexproof or not, so having access to multiple creatures on demand is an enormous boon for a deck that plays enchantments with recursive capabilities like Rancor.

It felt necessary to have one more enchantment that provided evasion, and Gryff’s Boon is actually quite good at doing that. Translating into the late-game is a niche, but overall positive benefit.

After finishing the tournament and having a few days to think about the deck and really get my thoughts on paper, a few things became clear to me.

Leyline of Sanctity was never a card that I wanted to bring in all four copies of. Drawing a copy of it (after one’s opening hand) is oftentimes a death sentence, and even against the Liliana of the Veil / Abrupt Decay decks, it is oftentimes better to just try to apply pressure after the first or second turn. The first discard spell is going to do significantly more damage than any that are drawn later in the game, and it is generally a better strategy to make the opponent’s hand destruction non-impactful by emptying your hand instead of spending a card (and four mana) to blank something that might never come.

Despite being cool and feeling good to cast, Open the Armory was usually not very good. Discounting copies of Dryad Arbor, Hexproof only plays nineteen lands. Open the Armory in a lot of cases was a fifth copy of Ethereal Armor…..that cost 1WW total to cast. This kind of difference is a big shift in tighter games, and Modern isn’t a format known for its forgiveness.

The third Temple Garden literally never mattered. My sample size is relatively small, but there were zero times in twenty rounds of play that I needed more mana that was specifically white or green and I didn’t have it.

Ironically the only place that Rest in Peace was a slam dunk was against Death’s Shadow Aggro, and even there if felt somewhat loose. Modern sideboards (white ones, more specifically) tend to have some of the most powerful interactive cards in the format, so these sideboard slots need to be something different going forward. Rest in Peace just isn’t needed against the Dredge decks to beat them, and isn’t impactful enough against most other matchups that one would expect to play against at a larger Modern tournament.

This card is the real deal. It isn’t quite a card that is good enough to maindeck, but it comes in very frequently. Many Modern decks function based on their ability to activate abilities for little to no mana. It doesn’t take long to realize how horrible entire archetypes become when the activated abilities in the decks cost two more mana:

Suppression Field is incredibly play/draw-dependent but can do work similar to Thalia, Heretic Cathar’s impact on Standard. I had an opponent lose because they played a Celestial Colonnade on the first turn (on the draw) and then died because their hand was two fetchlands and a Sulfur Falls. Suppression Field is by no means a hard lock, but in a deck that can apply pressure as proficiently as Hexproof, the extra turn or two that it buys can translate to what is effectively a Time Walk or two.

Last weekend I sleeved up Hexproof for another go-round and think that my newest list may be within one or two cards of the optimal deck for today’s metagame:

Creatures (12)

Lands (21)

Spells (27)

I know at least some portion of readers skimmed over the decklist, but I’m gonna stop you real quick.

This card is the real deal. Something that started as a joke while thinking of a replacement for Open the Armory ended up being a real contender.

Hexproof generally needs a mix of things in order to function:

· A hexproof creature

· A way to make the creature big

· Some avenue of punching damage through via trample or evasion

Open the Amory was nice because it pulled double-duty. It could provide the damage, the evasion, or even a form of lifegain in a pinch. Lunarch Mantle providing +2/+2 while also having the option to provide evasion for two mana is a really big deal. Most cards that provide evasion have diminishing returns (see: Spirit Mantle) and there aren’t many Auras that efficiently provide power and toughness for less than three mana. Lunarch Mantle isn’t the prettiest solution to the issue, but it’s a surprisingly elegant one.

This card is easy to write off, but I wouldn’t recommend it without giving it a few reps first.

As long as Suppression Field stays in the sideboard of this deck, it would be hard for me to imagine playing fewer than seven fetchlands in the deck going forward, if for no other reason than their ability to grab Dryad Arbor at instant speed.

To draw from the aforementioned example of playing against Dredge, there are several aggressive or linear decks that don’t play enough removal to require a hexproof creature. It is relatively common against Affinity or Infect to have the following first few turns:

Turn 1: Fetchland. In the opponent’s end step, fetch up Dryad Arbor.

Turn 2: White source (Forest and the other Dryad Arbor are the only non-white sources in the deck), two auras on the Dryad Arbor (using Dryad Arbor as mana).

Turn 3: Another Aura on Dryad Arbor, start attacking.

Having such redundancy in what feels like a hybrid between a combo deck and an aggro deck cannot be overstated, and raising the number of fetchlands, even if only by a little, can change the outcome of entire games.

In testing, the decks that gave Hexproof the most issues were Tron, Infect, and Affinity. Gut Shot is a way to try to pick off little opposing creatures for zero mana and has been testing well thus far. The difference between one mana (for say, Dismember) and zero mana is huge. This is further exacerbated by how much mana the Hexproof deck wants to spend every turn, trying to find the balance between interacting and applying the appropriate amount of pressure.

Gut Shot does tend to suffer against Infect (they are a deck full of pump spells, after all) but what it does that transcends physical interaction is that it forces the opponent to respect the card. Infect is a faster deck than Hexproof, but only barely, and only with an unblockable creature involved. Making the Infect player hesitate for a single turn changes the entire dynamic of the matchup, even if the Gut Shot isn’t drawn by the Hexproof player.

Against Affinity, Gut Shot is a fantastic way to kill a creature with a Cranial Plating attached to it or when the player tries to go all-in. Other than Ornithopter, most of the Robots are one-toughness creatures (or at least start off that way)

Gut Shot has a pile of other interactions that matter (see: killing creatures against Melira Company) but the intention of the slot in the sideboard was to shore up matchups against the linear aggressive decks that are slight faster than Hexproof, and Gut Shot is a card that does it magnificently.

This is the new piece of technology in the archetype that I’m quite proud of, as it solves a lot of the deck’s problems.

If there are any two decks in the format that smile when they see the opponent is piloting Hexproof, they are Tron and Infect. Ghost Quarter does a lot of work against both of these decks in that it can break up the “combo” from Tron while disrupting colored mana and creatures from Infect.

When playing in the Open two weeks ago, it always felt like, no matter the draw, the Hexproof deck was always a turn too slow when it came to killing the opponent. Kor Spiritdancer was the only thing that could get big enough to put them on a fast clock, but she gets exiled by Karn Liberated. The one-drop creatures rarely did enough damage to the opponent before Ulamog, the Ceaseless Hunger took over.

The Stony Silences and Suppressions Fields were only enough if they were on the play (as the opponent could just crack Expedition Map before the enchantments resolved if they went first), and even then weren’t always impactful enough. Casting one of the hoser enchantments meant taking a turn off from applying more pressure on the battlefield. Sure, the opponent may lose a card or two from their hand, but Tron has so many ways to find redundant pieces of the “combo” that the time the cards bought was almost lost when taking the time to cast them.

Ghost Quarter fixes a lot of these problems. Ghost Quarter eats one of its controller’s land drops, but it’s hard to find reasonable land destruction for a single mana. Think of Ghost Quarter’s use here as something more akin to Wasteland’s use in Legacy. While it technically produces mana, it is oftentimes used as a free spell to destroy a problematic land.

In this deck, a land that only produces colorless mana really only casts Kor Spiritdancer and Lunarch Mantle, making Ghost Quarter a free Stone Rain in the matchups where it’s important. That’s to say, even if it gives the opponent a basic land, the basic lands out of Tron don’t create problems, so is it really providing that much for the opponent?

Many people seem to forget that Infect doesn’t actually have any basic Islands in their deck. It’s quite realistic to Ghost Quarter a Breeding Pool in order to knock the opponent off the mana required to cast Blighted Agent, Spell Pierce, and Distortion Strike.

This biggest player here is Ghost Quarter’s ability to ruin the card Inkmoth Nexus. Unless the opponent doesn’t do anything on their turn, it is unlikely the opponent will have the mana to both activate the Inkmoth Nexus (making it a creature) and protect it with Vines of Vastwood. It’s also important to note that Vines of Vastwood is the only protection spell that saves Inkmoth Nexus from Ghost Quarter; Spell Pierce, Apostle’s Blessing, and Spellskite can’t properly interact with a Ghost Quarter, and there is a lot of power in the card being so narrow, yet deliberate.

If there’s anything I’m uncertain on in the decklist, it is the single copy of Spellskite in the sideboard and the two copies of Seal of Primordium in the sideboard.

The Spellskite is incredibly narrow and primarily for the Infect matchup (but has splash applications against other matchups that are already favorable) and it’s likely that it could just be something with wider applications or more impactful in the matchup (a copy of Melira, Sylvok Outcast may just be a better narrow hate card for the matchup; another Gut Shot isn’t quite as powerful, but has a longer list of uses).

Seal of Primordium is incredibly inefficient but does serve a role. Against a deck in the same vein as Affinity or Lantern Control, it is important to find pockets of “spare” mana when possible and not be locked into representing a removal spell or piece of interaction every turn for the rest of the game. Being able to find a place to invest two mana and threaten to use the removal spell is a valuable resource, albeit an expensive one. Being able to cast Seal of Primordium before Blood Moon resolves is also an enormous reason to stay pro-Seal. I want to look further into testing out Natural State and/or Nature’s Claim in this spot because having hate for artifacts and enchantments is incredibly important for the archetype, but doing it for a smaller mana commitment would be ideal in this strategy.

Moving on Up

Hexproof is on its way up the tier ladder in Modern, and it will burst through to the top soon. With a recent Top 8 at the SCG Open in Somerset, NJ and a growing number of fans (looking at you, Cedric), it is only a matter of time before people start taking the deck seriously. When Infect first started seeing play in Modern, people laughed at the deck until it kept winning. It’s Hexproof’s turn to make people laugh with Ethereal Armor, until it kills them.