It’s been a little over a month since Modern Weekend in Charlotte and Los Angeles, with those two Grand Prix serving to spotlight the popular format with

truly huge events. GP Charlotte is just one of the many major Modern events that StarCityGames.com has put on in recent years; these days, the SCG Tour® is

generally either a Standard or a Modern tournament, so we’ve grown accustomed to seeing the format get more love than it used to. Of course, next weekend

is the big Legacy return at #SCGWOR, but we’re talking in general.

I can’t pretend that I love Modern. If anything, the format that I love is Legacy, followed closely by Draft. You won’t find me in the anti-Brainstorm camp

in Legacy; if anything, you’ll find me celebrating

Brainstorm. I love the wild variety of decks in Legacy.

Modern might not have quite the diversity of Legacy, but honestly, it sure does have a ton of options for you to choose from. If you’re curious

about what I think you should play in Worcester for the SCG Tour®, I’ve talked about my favorite choices for Legacy, but this

article will focus on Modern.

At Grand Prix Charlotte, I played a bit of the fun-police, and chose Lantern Prison. At the event, I was joined by my favorite Muggle, Andrea, and I

described the deck I played as trying to make sure that no one gets to play Magic as quickly as possible, then describing the mechanisms of the lock.

“Basically,” I said, “this deck tries to put the other player into a sleeper hold.” [Smart players will think of it more as an ankle lock and tap out fast. –Ed.] I introduced her to numerous Magic players, and we each described to

her the basics of the many decks, in Muggle-speak.

“This deck makes a ton of cheap little robots, and they try to kill you as quickly as possible. Some of the robots even make all the other robots

go into a killing frenzy, and there is a robot-light-saber they can kill you with.”

“This deck spends several turns building up a perfect combination of real estate. With all the money it makes, it makes an absolutely insanely expensive

play other decks couldn’t even manage to make. Then it wins the game.”

“This deck makes a well-coordinated army that each make every other member of the army more damaging, and it uses their teamwork to kill you more quickly.”

“This deck makes a large number of powerful animals as quickly as it can, and they aggressively try to maul you.”

“This deck tries to protect its queen, and if it succeeds in doing so, she calls forth Cthulhu to destroy the world.”

“This deck throws away its cards to directly bring the opponent closer to death with every play, hoping that it can do it quickly enough and that you

aren’t prepared for the direct assault.”

“This deck attempts to just kick down the other player’s sand castle and kill them along the way with whatever.”

“This deck doesn’t intend to kill you in the normal way, but instead tries to make a single creature it has grow incredibly large so that you die in one

incredibly huge hit.”

It was fun trying to describe them in this way and getting the people who were playing what they were playing to describe their decks in non-Magic terms.

Some people were better at it than others, and Andrea seemed to like all of the descriptions. I’m sure you probably could identify a large number of the

decks, and maybe you would have your own ways of describing them to a non-Magic player, but I know that everyone involved seemed to enjoy the challenge of

fitting their deck into such terms.

“Wow,” she said. “Are there a lot of different ways to play this format? Is this how all formats are?”

If we compare things to Standard, we know that they aren’t. While there are a good handful of options in Standard, it doesn’t reach the level we see in

Modern, not by a long shot.

Take the Top 100 archetypes at the end of Day 1 in Grand Prix Pittsburgh, with about 1300 players. Seven archetypes had five or more percent of the field,

and the top two archetypes, G/W Tokens and Bant Humans, encompassed half of the field. Seventeen archetypes encompassed that Top 100.

Contrast this with Grand Prix Los Angeles, with eight archetypes at five percent or more, but taking six archetypes (Abzan Company, Affinity,

Merfolk, Burn, Infect, and Tron) to make up half of the same field, and 34 distinct archetypes in the Top 100. Like Los Angeles, Grand Prix

Charlotte had a lot of archetypes (36) for its Top 100 at the end of Day 1, and taking seven archetypes (Affinity, Jund, Jeskai Harbinger, Tron,

Burn, Abzan Company, and Infect) to make half of the field.

This is a remarkable difference.

It ends up making for a much wilder ride when you’re in a Modern event.

Digging a little deeper into the combined Top 32s from the Los Angeles and Charlotte events, you have the following:

Infect: 123456

Merfolk: 12345

Jund: 12345

Affinity: 12345

Burn: 12345

Abzan Company: 1234

Jeskai Harbinger: 1234

Bant Eldrazi: 123

Bring to Light Scapeshift: 123

Ad Nauseam: 12

RG Tron: 12

Scapeshift: 12

Blue Moon: 12

Grixis Control: 1

Naya Company: 1

Kiki-Chord: 1

Bant-Knight Company: 1

G/W Tokens: 1

Rock: 1

Grishoalbrand: 1

Hatebears: 1

Elves: 1

Bushwhacker Zoo: 1

Jeskai Control: 1

Titan-Breach: 1

Abzan: 1

Grixis Delver: 1

(Italics represent a Top 8 finish in either Grand Prix, with an underlined and bolded number indicating a GP win.)

There are some important considerations to look at here.

First of all, G/R Tron, despite being among the most-represented of archetypes in both Grand Prix, fell apart on Day Two. Twelve Tron players were

in the Top 100s of Day 1. By the end of Day 2, only two players were in the Top 32 of their respective tournaments. An average result would have

ended up with four such players in the Top 32. Joe Lossett was one of those who succeeded, and he didn’t just Top 32, but he made Top 8.

This says to me that either Tron was just poorly positioned for the weekend, it simply isn’t in the most elite portions of the game, or that most people

are simply not playing the right version of Tron. This makes a lot of sense, in some ways, since Tron generally is at its best when it is preying

upon certain fair decks like Jund, and it is worth noting that the ban on Eye of Ugin did not leave Tron unscathed.

Creatures (8)

Planeswalkers (6)

Lands (18)

Spells (28)

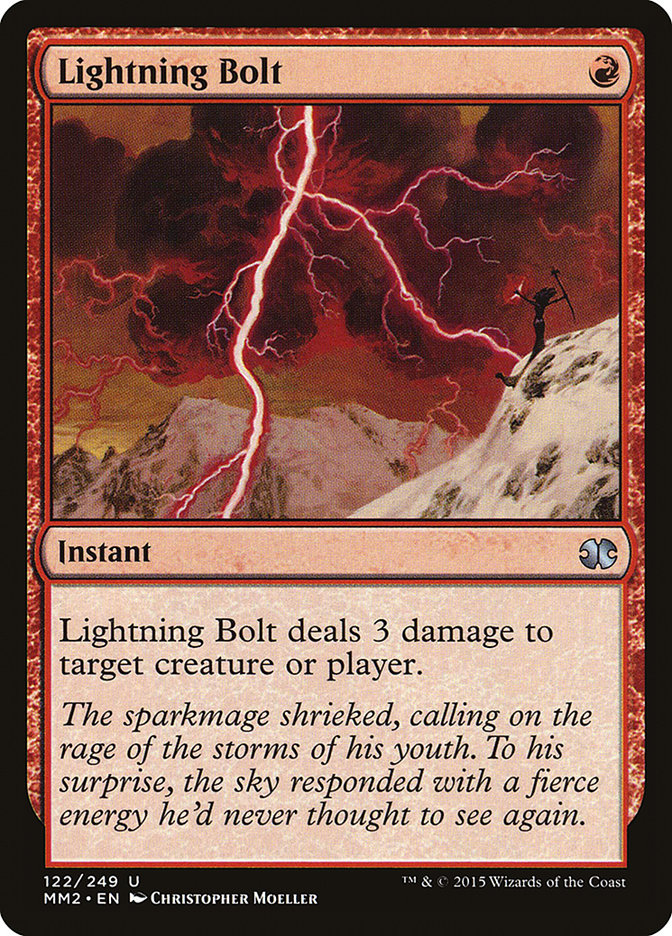

- 4 Lightning Bolt

- 1 Forest

- 3 Oblivion Stone

- 4 Sylvan Scrying

- 4 Chromatic Sphere

- 4 Chromatic Star

- 4 Expedition Map

- 4 Ancient Stirrings

Sideboard

If Joe is doing something different than other people, perhaps it is in some of the small choices, primarily in the sideboard. To me, this sideboard is

gloriously done. Forest in the sideboard is a strong acknowledgment of Ghost Quarter, one of the most difficult cards for the deck to deal with. Sudden

Shock is an awesome response to the lightning-fast decks, especially Infect. Warping Wail is another awesome card, making sorcery spells look far, far

worse. I could speak at length about every sideboard card choice, but they are collectively a clear indication of a thoughtful, deeply powerful sideboard.

If Tron was underrepresented, Infect is in the exact opposite boat. Eleven players were at the top of the field, similar to Tron’s twelve, but in the end, six players ended in the Top 32. This is quite impressive. While none broke the Top 8, my old friend Lan D. Ho finished at 13-2, tied for Top 8,

with this list:

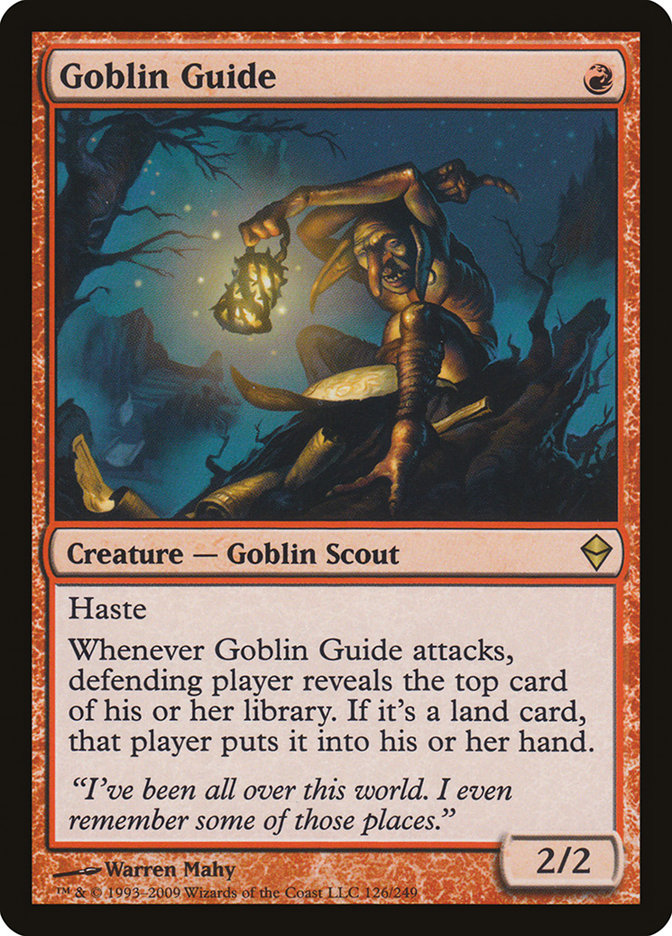

Creatures (13)

Lands (20)

Spells (27)

There is nothing particularly mind-blowing about Lan’s build of the deck. Maindeck Viridian Corrupter is well within the range of normal, and the

collection of primarily reactive cards in the main deck (2 Apostle’s Blessing, 1 Dismember, 1 Spell Pierce, 2 Twisted Image, 4 Vines of the Vastwood) is

basically pretty normal.

What makes this deck so frightening and so powerful isn’t that it is the fastest deck able to assemble a kill, but rather that it is a deck that punishes

the opponent for letting their guard down. Take this rather classic scenario that I’m pulling from my imagination:

Lan is attacking with a Blighted Agent with a Noble Hierarch on the battlefield, as well as a Misty Rainforest, a Pendelhaven, and a Breeding Pool. His

opponent, Glenn, taps a mana and casts Lightning Bolt to kill it. Lan taps Pendelhaven to pump the Hierarch, then pays two life to use Mutagenic Growth,

taking it out of range of Bolt. Glenn casts a Path to Exile and Lan responds with a Vines of Vastwood with kicker. At that point, even if Glenn has another

removal spell or counterspell, Lan could have another Vines of Vastwood or Apostle’s Blessing or even a Spell Pierce. Just as is, Lan is coming in for nine poison, which very likely is lethal.

Unless you are actually prepared for A Showdown, the proper play for Glenn is to, very likely, take two poison, and then in the end step begin a fight over

Blighted Agent, if only to make the fight “just” about Blighted Agent, rather than a fight for the entirety of the game. Even then, there are actually many

situations where this more conservative play, the play where you accept the poison damage in the now, is also incorrect.

Infect is the scary beast of a deck that it is just because of this dilemma for an opponent. You can’t take the nickel-and-dime-ing all day, but if you

fight the Infect deck at the wrong moment, that is often a game-losing choice, if not a match-losing one.

Right now, I’m confident in saying that Infect is my favorite of the mainstream, well-accepted, powerful, popular decks in Modern. There are draws with

Infect that are utterly busted, where you will generally beat nearly any opponent. At the same time, you can play a patient game, not going for the

comborific win, but rather taking your time and going for the kill more at your own leisure, if you “go for it” at all.

This deck’s performance at the two Grand Prix is about as I would expect it, and if I were to recommend a person play something in Modern, and I only knew

they played a fair amount of Magic, I’d tell them to choose this deck.

The next deck I’d recommend to someone is what I’d suggest for two kinds of players: players who are new to Modern or players who have a lot of time to

practice. That deck is Merfolk, the winner of GP Los Angeles.

Creatures (27)

- 2 Kira, Great Glass-Spinner

- 4 Lord of Atlantis

- 3 Merrow Reejerey

- 4 Silvergill Adept

- 4 Cursecatcher

- 1 Phantasmal Image

- 4 Master of the Pearl Trident

- 1 Tidebinder Mage

- 4 Master of Waves

Lands (8)

Spells (25)

Sideboard

There are many ways to build a Merfolk deck in Modern, by which I mean only the tiny edges of the details. With few exceptions, you will have a particular

set of lords and the regular support cards like Silvergill Adept, Mutavault, and others. Where I strongly recommend the Legacy build of the deck to a new

player, I am less strong in my recommendation of the Modern deck to a new player because the Legacy deck includes the powerhouse combination of free

countermagic (thanks Daze and Force of Will), and, if you want it, Chalice of the Void.

While you can certainly run Chalice of the Void in Modern as well, the deck becomes much harder to pilot if you don’t get to rely on the intense power of

free countermagic. The decisions you’re making are largely otherwise the same: when do you choose to accelerate the game, and when do you make a choice to

(slightly) take your foot off of the throttle.

The question of pacing is so important that I

once wrote a short article about it. For Merfolk, every creature lost tends to be far more meaningful than it would be for another deck.

Creatures build upon each other in this deck in a way that is explicit and powerful. At the same time, in many instances you have to make decisions about

what kind of speed the game is going at. A 2/2 Cursecatcher can represent six life over the course of several turns if you toss it away to kill an opposing

creature, or it can represent six damage later in the game if two new lords have joined the table and an extra Elemental is on the battlefield because it

isn’t dead.

Pacing is actually a quite difficult skill, and without explicit countermagic (until you get to the paltry pair of Spell Pierce in Sluttsky’s sideboard),

you often can’t actually be a full aggro-control deck, even if you are oft-times playing the game from the perspective of tempo. All of this makes me lean

a little bit more towards suggesting a player play Infect, just in general, if they feel like they are particularly talented, but Merfolk has a series of

straightforward decisions in very many instances, so it can be a great choice for many players.

On the exact opposite side of the spectrum is Jund, firmly stepping into the midrange space (and, incidentally, singlehandedly making me rethink my

decision to focus on Lantern as of late).

Creatures (13)

Planeswalkers (4)

Lands (23)

Spells (20)

This deck may very well be the platonic ideal of a midrange-control deck. Every creature isn’t just a card that might kill the opponent, but it is also a

card that can help you establish control. The deck is jam-packed full of answers, and in its totality, Jund, especially as it is built here by the

inimitable Mike Sigrist, is just set up to kick down an opponent’s sandcastle.

It’s been a classic ideal ever since Sol Malka pioneered The Rock way back in the late ’90s. Black is particularly well-suited to messing with someone’s

plans because of discard, and pairing it with green was a classic way to bring flexibility to your answers, be they Maelstrom Pulse and Abrupt Decay now,

or Pernicious Deed then (at least after I convinced him to play it).

This deck hasn’t seen much in the way of changes in the last few years, though we’re getting to a point where Kalitas, Traitor of Ghet might end up being a

near-default choice. This is understandable, given how well-positioned the card is. Kalitas helps you recover from the early-game, but it also stymies any

number of potential plays that could otherwise be a problem, like the transfer of Arcbound Ravager counters, among many others.

Jund is also a really great choice if you are less familiar with the format at large, if only because of the blunt force of so many individual cards. Your

hardest decisions will generally be the decisions that are hard with any deck – i.e., the best potential sequencing for your plays, especially in

the early-game – so it’s not as though that challenge is unique. The difficulty that is more specific to Jund is just learning how to best utilize discard;

this is one of the most powerful elements to the deck, and yet very easy to mess up simply by not being aware of what to take from what deck.

I actually especially like Sigrist’s maindeck with a very elegant set of card choices. The single Slaughter Pact almost makes one think about the ancient

past of Splinter Twin, but I expect that mostly this card is here for Infect and Affinity, both of which are worthy of respect. I’m quite sympathetic to

that, having played decks with as many

as three maindeck.

Speaking of Affinity, it also one you can expect to see at top tables, and though it did have a lot of representation among the top tables of both the

Grand Prix this weekend, it did underperform expectations, given that 21 players were among the top players in the two GP with it.

Creatures (27)

- 4 Arcbound Ravager

- 4 Ornithopter

- 1 Master of Etherium

- 3 Steel Overseer

- 3 Memnite

- 4 Etched Champion

- 4 Signal Pest

- 4 Vault Skirge

Lands (17)

Spells (16)

A lot of people who are being given a deck for their first competitive Modern deck are handed Affinity. This is largely because it is probably the most

explosive aggressive deck in Modern, and it can get draws where the game feels like it ends almost immediately, with little to no hope for the opponent.

Playing this deck as an inexperienced player is a huge mistake.

Of any aggressive deck in Magic, this is the one that I’d least suggest get handed to an inexperienced player. This deck is absurdly powerful in

those initial turns, but there are a great many games that, played properly, Affinity will win by the skin of its teeth. This is in large part because of a

few cards and simply how difficult it can be to play them, especially in the face of opposition.

Arcbound Ravager is an awesome card. In fact, it is one of the biggest reasons that the deck is as absurdly powerful as it is. However, balancing when to

let a Ravager go versus when to keep it around is actually incredibly difficult. There are even times when you’ve gotten to the point in a game when it is

appropriate to go all-in (or nearly so) in order to bring the life total to the right spot where a Galvanic Blast for two (let alone four) could be

top-decked to win the game.

The truly skilled players with Arcbound Ravager often end up in plays that would be hard for a novice to come to, like attacking with creatures, going

nearly all-in with a Ravager, and then, after combat, making a Blinkmoth Nexus into a creature and then dumping everything onto the Nexus as a kind of

horrific insurance policy, bringing death from the sky should your opponent ever tap out.

Knowing when to go down which path doesn’t just take intelligence; it also takes experience.

Inkmoth Nexus is similarly hard to play because of the time investment required to make a kill with it. Since one side of the deck is killing with normal

damage, a decision to invest in the poison half of the deck can be entirely what a game is about, for good or for bad. Again, this isn’t a thing that most

players, even smart, good players, can do without having put in hours to learn.

Finally, when you come to the sideboarding, you have one of the most difficult questions in Magic sideboarding: how much can you afford to change to still

be the deck you want to be. For Affinity, the answer is usually “almost nothing.”

If you focus on this deck and practice with it, this is a worthy choice. But I suspect that this deck underperformed (despite it still being so widely

played) because it is a very difficult deck to pilot, more than anything else.

Which brings me to the other popular deck that I usually don’t recommend people play, Burn.

Creatures (14)

Lands (19)

Spells (27)

This is the highest-placing Burn deck from Charlotte, and it has the highlights of the archetype that make it so difficult to play against. It is

single-minded about killing the opponent and is mostly built out of cards that deal damage immediately and directly (or nearly so). Fourteen people played

Burn in the Top 100 of Day 1, and in the end, five of them made the Top 32 of the event, indicating the deck played out pretty close to expectations.

One of the highlights of Shea’s build that set it apart from some other builds is the absence of a particular card:

Shea is barely stepping into green, with a full set of Destructive Revelry in the sideboard powered off of a single Stomping Ground.

Like Affinity, this is a deck that I don’t suggest playing without a ton of practice. Even more so than Affinity, Burn often wins by the barest of inches

(a fact I often like to reflect upon), and one thing that it

lacks is Affinity’s ability to just vomit its hand onto the table and destroy the opponent while their opponent watches on in disgust.

That being said, Burn also has the advantage of being one of the least properly prepared-for decks out there. People play against Burn a lot in

playtesting. They very rarely play against someone who is good at Burn. This often lets people believe that they are safe when facing it down, and

it can mean that, if you are a competent Burn player, you can steal a large number of games from people who simply don’t realize just how much danger they

are in.

Shea’s build has a number of things about it that I don’t care for exactly, but they are all fairly minor. More importantly, it has one aspect that I very

much like. It doesn’t run Wild Nacatl, a card that I’ve never really been too excited about in this archetype.

Abzan Company, Jeskai Harbinger, Bant Eldrazi, and Bring to Light Scapeshift all also had a large number of people playing them to great success recently.

Of these, Bring to Light Scapeshift is the most intriguing one to me, simply because it had such a high success rate, relatively speaking, including a Top

8.

Modern is always on my mind, and as I’ve indicated, I think there are a wide variety of excellent choices open to you. I’d been planning on sticking to

Lantern, but the shifting of the metagame has left me hunting a specific favorite that’s best suited to me (though I’m leaning towards Infect or Jund).

Legacy is always also on my mind. However, as these

spoilers for Eldritch Moon keep coming out, I’d have to say the card I am thinking about most in Standard is pretty adorable. I’ll leave you with

it.